Drunken Master and the Impossible Move

I had a Tai Chi teacher named Ben when I attended the program in mime acting. He was a former boxer, and firmly believed that Tai Chi was the most efficient of all fighting styles. To convince his, not so fighting keen students of this, he alternated his lessons with showing us kung-fu films on VHS.

One of the films was Drunken Master, where the main character, performed by Jackie Chan, is the disciple of an alcoholic master to learn 8 different kung-fu fighting styles. The central principle of the training is to use imbalance and simulated inebriation to confuse the opponent. The fighting styles had names like ”The God Tso with the Firm Neck grip” and ”The God Li, a Drunken Cripple with Strength in the Right Leg”.

I was fascinated by Chan’s ability to bounce around in unpredictable sequences, constantly oscillating between losing the balance and regaining it. There was also a sense of humor in the film that I liked, and that differed from the other, more serious, kung-fu movies.

At the end of the film, Chan’s character faces a truly evil and dangerous opponent. The drama in the scene in heightened by the music, and for a while, it looks really bad for Chan. Then, suddenly, I see him do it; the impossible move! From lying flat on his back, he rises to stand up straight, without using his hands for support.

I was speechless. That was the only movement I had, until then, declared as totally impossible. I had only seen it performed once; when Count Orlok rises from the coffin in the original Nosferatu film. Although I was pretty certain the actor had received some help in that scene, perhaps with a plank behind his back. In Drunken Master, on the contrary, I now saw how Chan literally flew up from lying down to standing, using no facilities but the ability of his own body.

I decided then and there to learn all of the kung-fu sequences in the film.

Jackie Chan

Jackie Chan was seven years old when he was sent to a Peking opera school in Hong Kong. There, he was trained in acrobatics and fighting styles, but not taught to read or write. After graduating, he began working as a stuntman. The drunken fighting styles featured in Drunken Master were choreographed by Jackie Chan and the director Yuen Woo-Ping.

Nosferatu

Nosferatu is a German horror movie from 1922 directed by F.W. Murnau. Murnau originally wanted to adapt Dracula by Bram Stoker, but didn’t obtain the rights. He then decided to create his own version, changing several scenes and giving the characters new names. Count Dracula, for example, became Count Orlok. Stoker’s widow later sued the company behind the film and claimed that they should destroy all copies. However, the film had already been distributed to several countries and was thus preserved in posterity.

Video violence

This took place in the time before the internet and finding a VHS-copy of Drunken Master turned out to be quite difficult. There was a ban on depiction of violence following the controversy surrounding the horror movie The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and kung-fu films were regarded as a form of harmful video violence.

Eventually, I managed to buy a VHS copy under the counter at a small video store in Lilla Essingen. The Swedish edition had been renamed Örnens klor (The Eagle's Claws), which was a bit strange given the film’s actual content. It turned out the cassette was partly demagnetized, but the sequences featuring the Eight Drunken Gods were mostly intact, and I was thrilled.

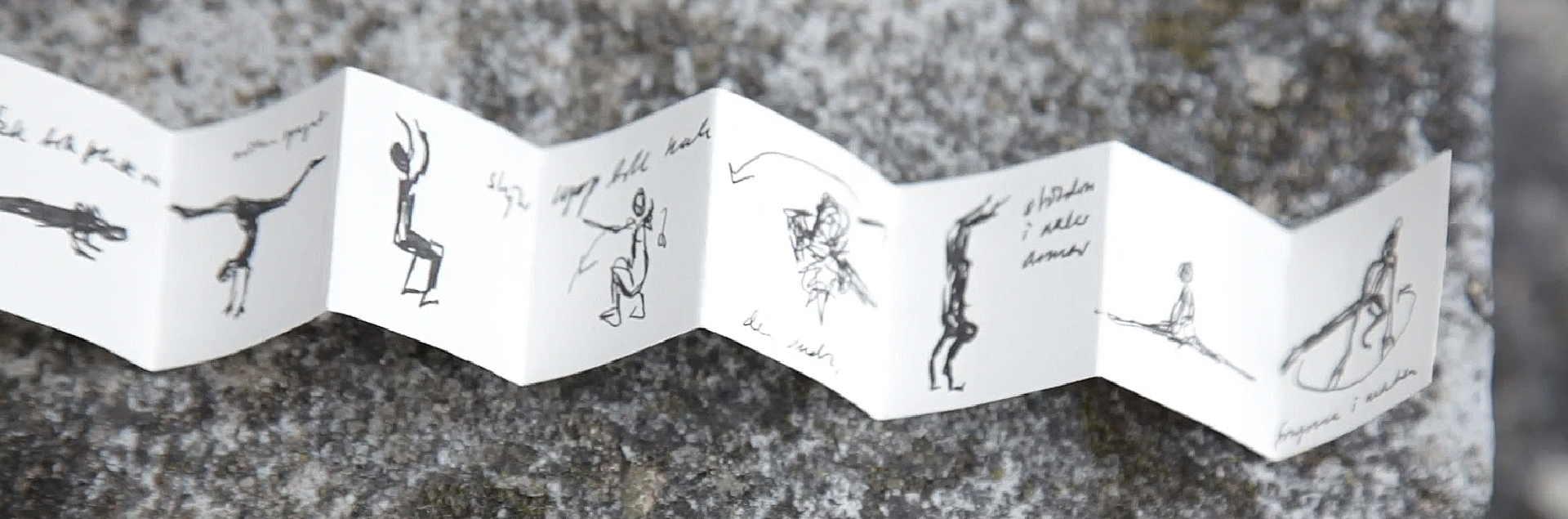

The Sketches

There was a video editing machine at Filmverkstan in Stockholm that I could use. I rewound the film back and forth at different speeds to study and draw the movements, adding arrows to remember which direction they were aiming for. In the middle of the page, between the sketches, I wrote: ”if you pretend to lose, you win.”

Nothing felt impossible.

Possible and Barely Possible Moves

My initial intention was to use the drawings to learn to perform the movements in the same way as Jackie Chan did in the film. The focus then shifted to an investigation of how my body could arrive at the different positions shown in the drawings. I chose 23 sketches from the poster, each of which became a starting point for a physical improvisation where moments of imbalance were to be included. Another prerequisite was that the movement should be able to repeat in a loop.

The improvisations where filmed using a fixed action camera. I didn’t decide in advance how the movement should be performed, but let the drawing, the inspiration of the moment, and the body’s ability direct the course of events. It soon became clear that certain sketches were relatively easy to interpret, while others were considerably more difficult. Performing a backflip from a jetty, for example, appeared as completely impossible, and in that case, the failure to execute the movement became the material used.

Design

A loopable part of each movement improvisation was cut out and turned into an animation using rotoscopy, a technique in which filmed footage is used as the basis for animation. By drawing the contours of the movements, they could be rendered in a way that was both natural and stylized. The illustrative manner accentuated the motion and, in a sense, also depersonalized the performer. It allowed subtle details in the movements to become more visible; such as when the toes brace backwards to maintain balance, or when the shoulder blades lift from the ground as the legs kick upward.

The animations were created in 12 frames per second, and were slightly slowed down. They were placed in various filmed, deserted settings with wihite frames around them to mark them as sections in time.

GIF Animations and Loops

To make the films play and loop automatically, they were exported as GIFs, which is a format with exactly those capabilities. The films therefore don’t need to be trigged to start playing. GIF stands for ”Graphics Interchange Format”. It was developed as early as 1987 to transfer images quickly over the internet. The ability to store and play multiple images in a loop was a side effect, but it is this feature that has contributed to the GIF’s continued use, despite its limited image quality. The movement and the repetition attract attention, which has made it a popular format for short, often comical, memes and advertising banners. I thought it was a useful format for presenting the animations in a digital environment. The ability to turn a few seconds of animated film into a perpetuum mobile also felt very appealing.

The loop's seamless, infinite repetition creates a kind of breathing space. The absence of a beginning and an end, and the monotony that arises from that, alters the sense of time. The movements appear as a kind of recurrent spell, where attention can wander, dissolve, or perhaps get stucked. The animations take on the character of signs for various states or conditions, open to being filled with new narratives.

Augmented reality

I got in contact with the Austrian company Artivive while it still was still a start-up. They were interested in having artists use their app for augmented reality. The technology was well-suited for displaying GIF animations in various ways.

The Artivive app links images and films uploaded to its system through image recognition. When you point your phone at a recognizable image, the film is mapped over it as a digital layer. If the image changes, for example rotates, the film adjust accordingly. It gives the impression that the animation is an integrated part of the surrounding environment, seen through the camera lens.

The technique made it possible to present the animations alongside analog drawings and paintings, which was especially useful in exhibitions and books. The method also echoed the process of letting an image serve as an impulse for movement. The drawings used to trigger the loops as augmented reality, became a kind of pendant to the original sketches; open to inner visualizations and new physical interpretations.

To view the still images below as animations in augmented reality, you need to download the Artivive app. (It’s free).

View-Master

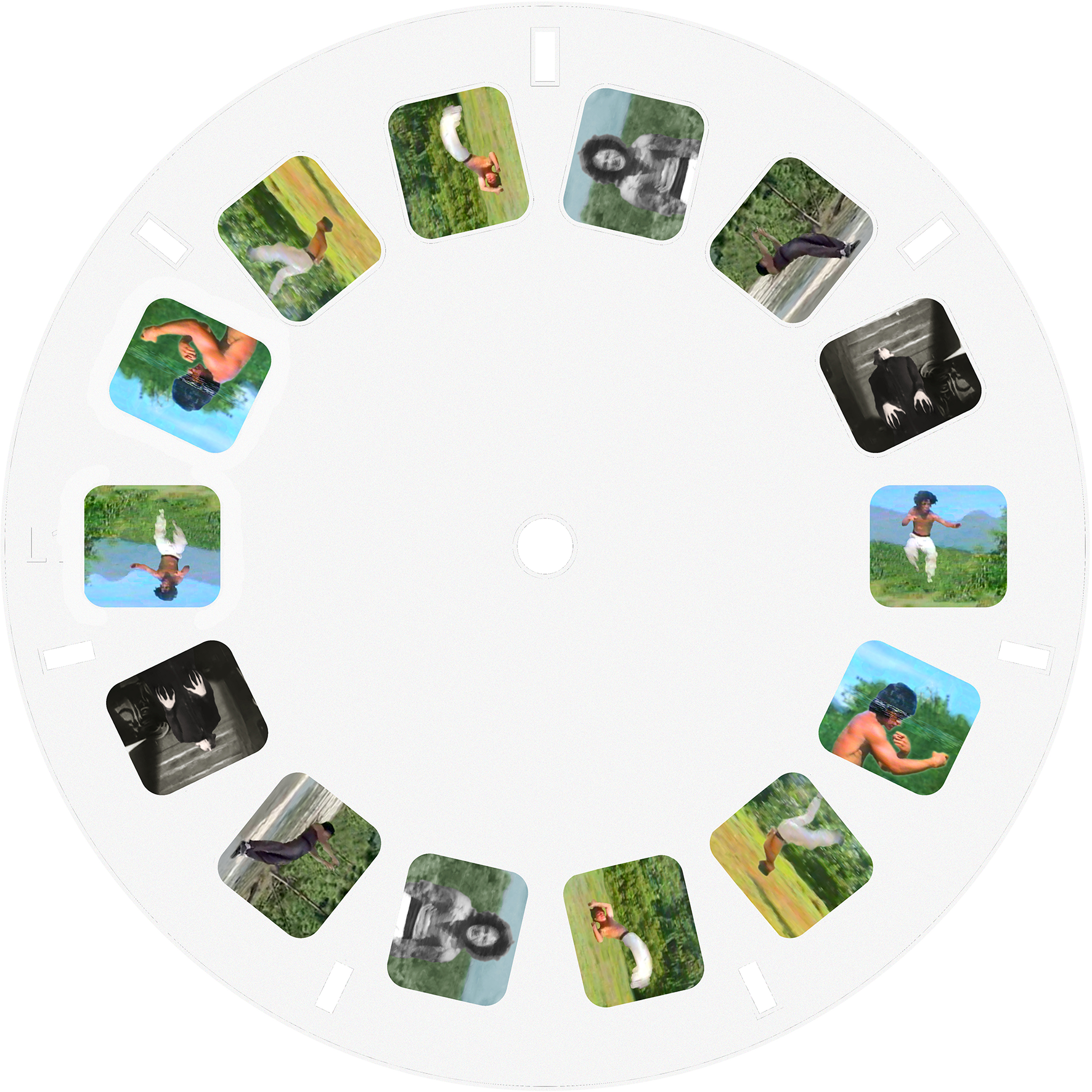

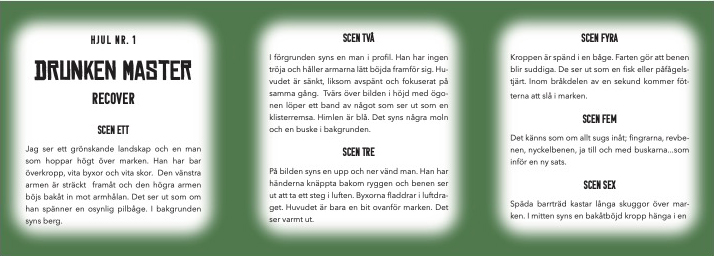

I attended a course at Valand called ”Publication in the Expanded Field” and decided to create a View-Master reel using some of the still images I had extracted from the VHS tape of Drunken Master. To my great joy I found a working View-Master at Myrorna and a print shop in England were I could produce image reels for it.

The View-Master is a device for viewing stereoscopic images, invented in the U.S. in 1939. Each reel holds seven pairs of images, which are rotated manually using a small lever. In certain models, the photographs appears when the device is pointed to a light source, while others have a small built-in lamp. The illusion of depth is created by photographing each image from two slightly different angles. This can be achieved with a stereo camera (with two lenses) or with two separate cameras placed side by side at a distance of 65 millimeters, which is roughly the distance between human eyes.

To make the still images from the VHS tape stereoscopic, I had to create a digital version of that process. The images were separated into layers and arranged as a 3D scene in After Effects. They were placed at different depths, like in a viewing cabinet, adjusted in size, and captured from two slightly different angles using a virtual camera.

The stereoscopic format gives the images a sculptural quality. They appear much larger than the small physical device you hold in your hands. The View-Master also blocks out all other visual input, creating a sense of intimacy with the scene and an experience of peering into another kind of realm.

The limitation and focus that the View-Master and the stereoscopic format offered felt like an appropriate way to honor the once so exclusive image material. In addition to the six stills of Jackie Chan, I included one image of Count Orlok, as he performs the impossible move. Alongside the image reel, there is also a booklet in classic View-Master design containing image descriptions for each scene.

Trial and Error and the Experiment

The moment of imbalance and loss of control interests me as it establishes direct contact with something real happening. When everything works, we don’t reflect on it, but when something goes wrong, and there’s a scratch on the record, our attention sharpens on the present moment and our emotions are stirred.

In Drunken Master, a combination of balance and imbalance are used to confuse the enemy. The unpredictability of the movements makes it difficult for the opponent to anticipate what will happen next. It is reminiscent of how certain animals pretend to be injured to lure predators away from their cubs or nests. The irregular pattern of movements draws attention and makes them appear like easy prey.

The sketches became keys to the work in the project Possible and Barely Possible Moves. Their expression of belief in the possibility of anything created an inspiring counterpoint to the limitations of my own physical body. A sketch of a movement exists somewhat independently of its original context. Just as letters in an anagram change places, or as when reading a word backwards, the sketches became impulses for exploring movements, rather than attempts to imitate something predetermined.

Losing balance and control were used not only as methods for generating material, but also as ways to challenge and surprise myself. The documentation made it possible to capture the quality of the moment and the unpredictable, and to transfer that into animation. The requirement for the material to loop was essential, as I wanted to use the GIF format. The loop also made it possible to study and emphasize details in the movements, which gain an additional dimension when shown through augmented reality.

The fascination with ”the impossible” has been a starting point for the work. The form that it has taken, through the physical feats of Count Orlok and Jackie Chan, can be seen as symbolic inspiration. However, it is the attempts and abilities of my own physical body that have been central to the process. Whether I succeeded in performing a movement or not, was not the main concern, but rather an interest in how the different attempts evolved.

The unforeseen, and the disruption from an original intention, can contribute valuable material and new ideas. The project Possible and Barely Possible Moves and the way it has developed, can be seen as a result of that principle.

”Nobody knows what the experiment is worth, but it’s better than sitting on your own hands, I reckon”.

I don’t know where this expression comes form, but it has followed me over time. It carries a sense of encouraging anticipation, and an openness to whatever might come.

References:

Bacon, Simon (red), Nosferatu in the 21st Century: A Critical Study, Liverpool University Press (2022)

Barker, Timothy, Korolkova, Maria, (red) Miscommunications: Errors, Mistakes, Media, Bloomsbury Publishing (2021)

Baumgärtel, Tilman, GIFS, Verlag Klaus Wagenbach (2010)

Guedes, Gabbi, Come to life realism: View-Master reels and the legacy of stereoscopic imperalism, Visual Anthropology Review no 40, (2024)

Höjdestrand, Erik, Det vedervärdiga videovåldet, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis (1997)

O'Reilly, Sally, The Body in Contemporary Art, Thames & Hudson (2009)

White, Luke, Legacies of the Drunken Master: Politics of the Body in Hong Kong Kung Fu Comedy Films, University of Hawai'i Press (2020)