“antike workes, and monstrous bodies, patched and hudled up together of diverse members, without any certaine or well ordered figure, having neither order dependencie, or proportion, but casuall and framed by chance” (quoted from Michael L. Hall p.79. In: Essays on the Essay)

Introduction

The Smallest of Worlds / #See You At Home is an investigation into the private space and its meaning in times of ubiquitous connectivity and global pandemic crises.

Today, the domestic space can no longer be considered as an isolated one. Rather, it has become a transitory space that negotiates the ambiguous relationship between the home as a place of refuge and comfort, serving as an intimate archive for the preservation of identity and memory, and the home as an exhibition space, a node in a public and global network of the sharing economy that continuously trades personal data.

Under these conditions, our homes and houses are more than ever part of a multi-layered public sphere that has profound implications for our relationship with the built environment we inhabit and enact (perform in) daily.

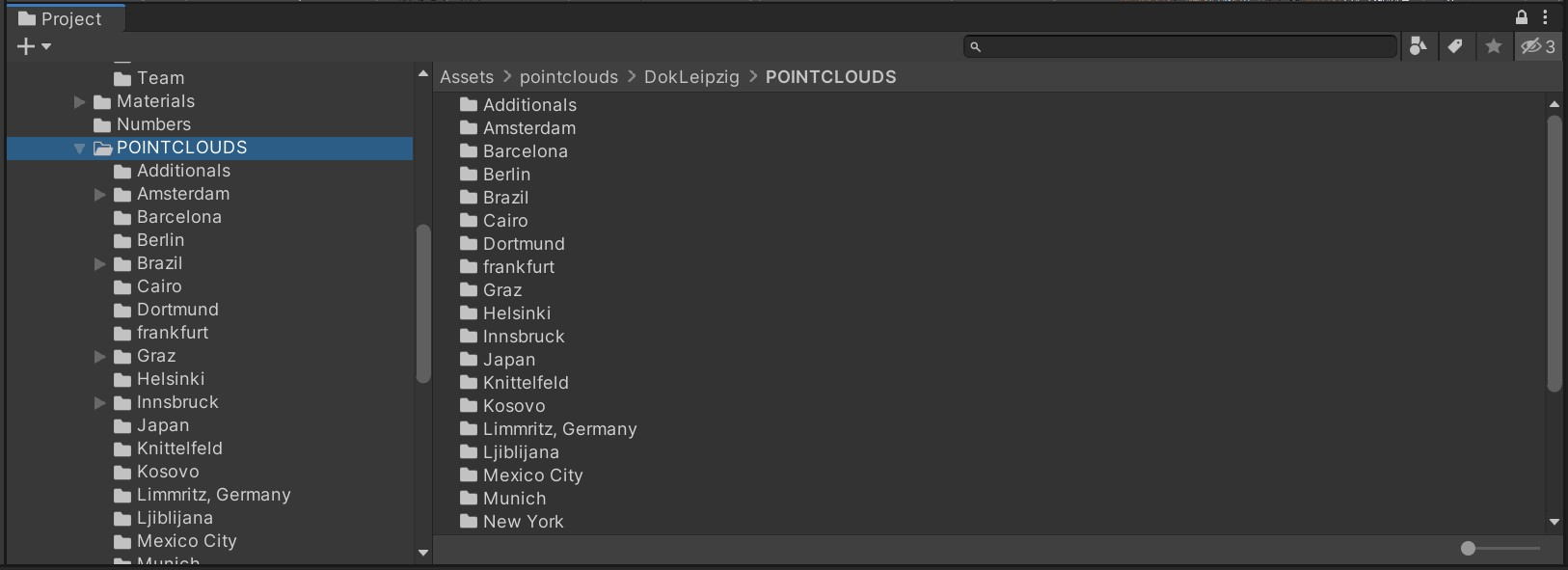

The Smallest of Worlds / #See You At Home has been an ongoing participatory project that reflects on our everyday domestic life between private and public spheres, and thus on our relationship with living spaces in general. The project consists of a collection of hundreds of three-dimensional documents from domestic moments and homely memories taken between 2019-2021 in more than 40 different countries and during the most intense periods of self-isolation and home confinement.

Collaborators

Bettina Katja Lange, Joan Soler-Adillon

Format

Multimedia Installation, Online, ... ..

Exhibtions

- Ars Electronica Deep Space in collaboration with Screen Institute, Linz (Austria), April ..., 2024.

- Diametrale Innsbruck, Interactive ... 2023.

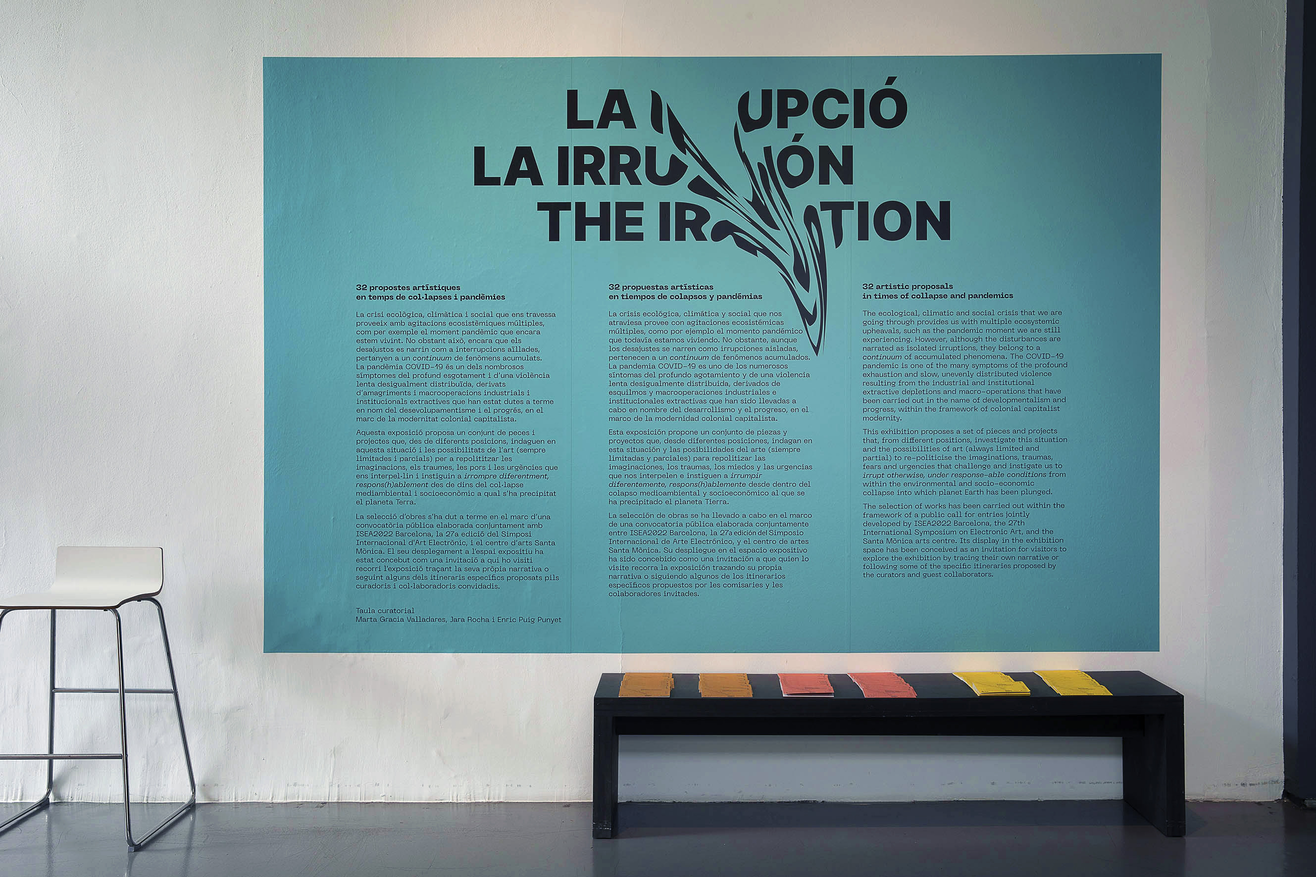

- ISEA 2022 Barcelona (Spain). June 09 to Aug. 21, 2022.

- Segal Center Film Festival on Theatre and Performance New York (USA). Mar. 01 to Mar. 21, 2022.

- Goethe-Institut Peking (China). Nov 6 to Nov. 31, 2021. Solo Exhibition

- ETH Zurich, Department of Architecture (Switzerland). Sep. 23 to Oct 29, 2021. Solo Exhibition.

- Les Ailleurs. Le festival qui explore l’immersion. Official Selection. La Gâité Lyrique, Paris (France). April 6 to July 18, 2021.

- VRHAM! Virtual Reality & Arts Festival. Official Selection. Hamburg (Germany). June 6 to 12, 2021.

- CPH:DOX, Copenhagen International Documentary Film Festival, 2021. Official Selection. INTER:ACTIVE. April 21 to May 21, 2021.

- DOK Leipzig 2020, Festival for Documentary and Animated Film. Official Selection, DOK:Neuland official, Extended Reality: DOK Neuland. Museum of Fine Arts, Leipzig (Germany) October 27 to November 1, 2020.

Tools and Technologies

The Game Engine as an Essayistic Laboratory

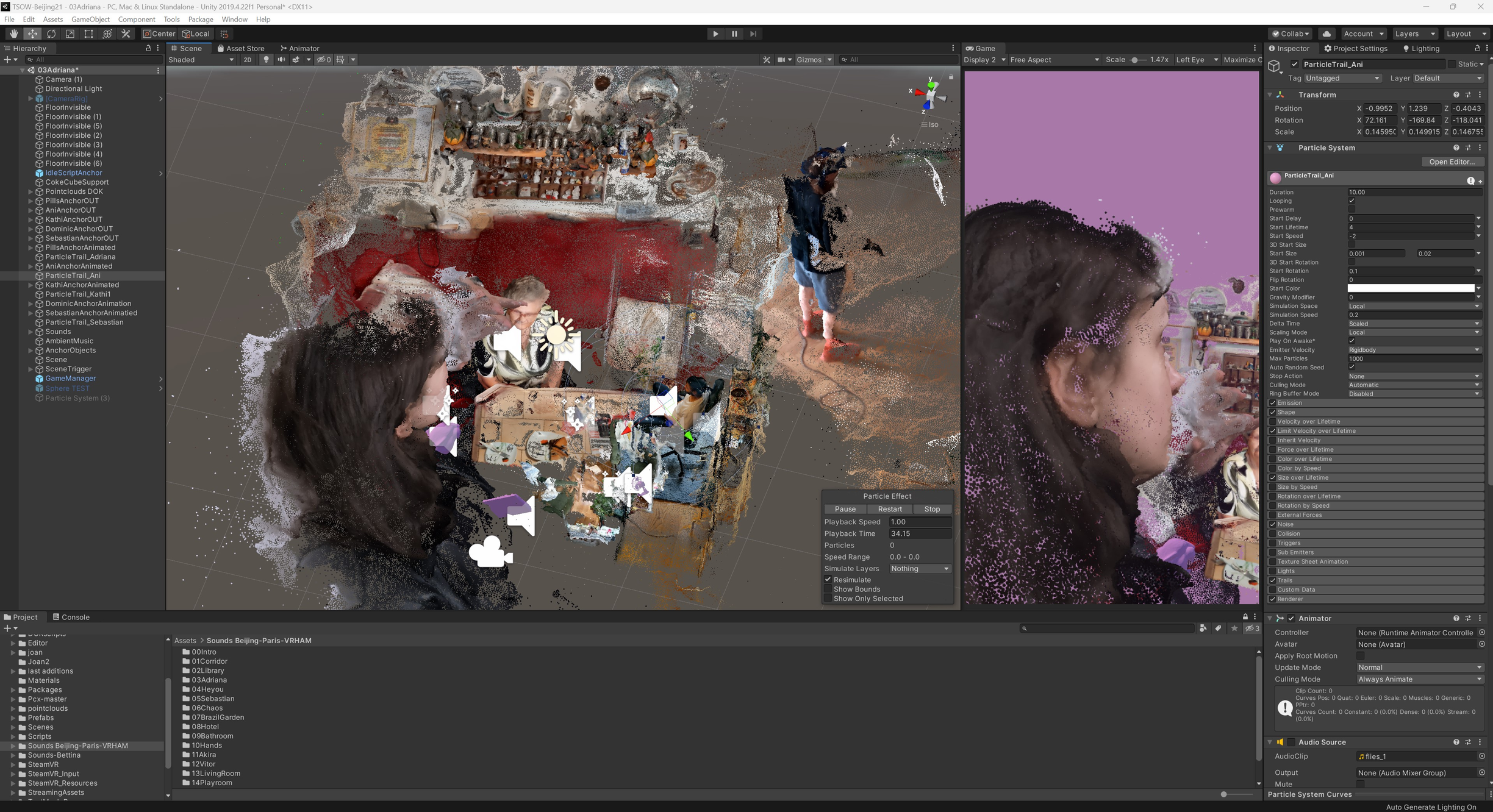

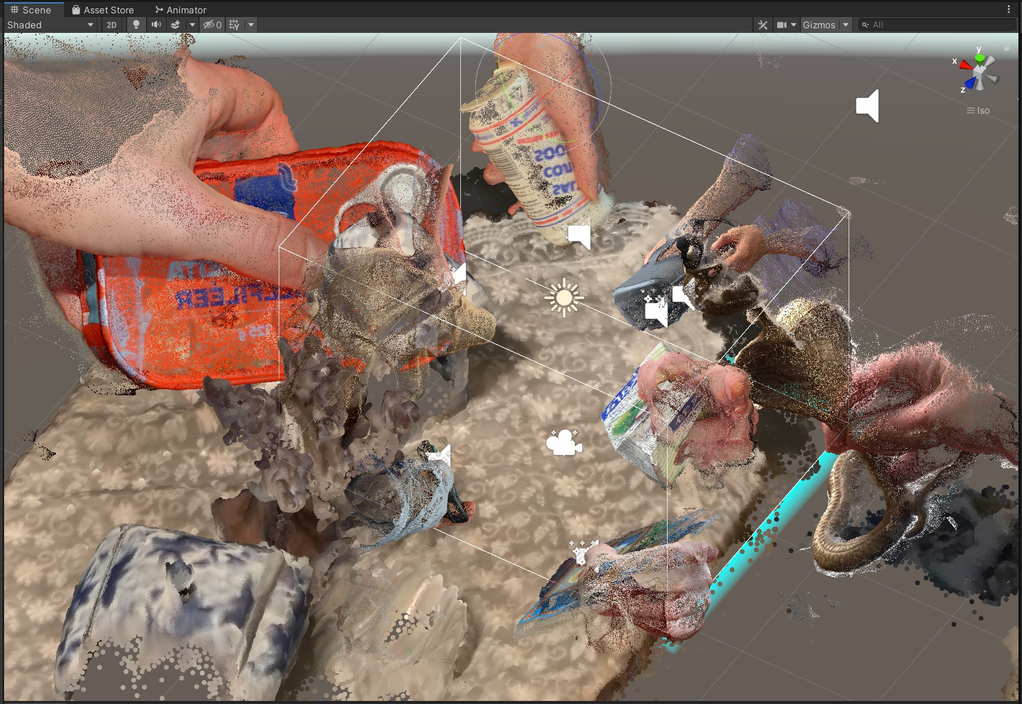

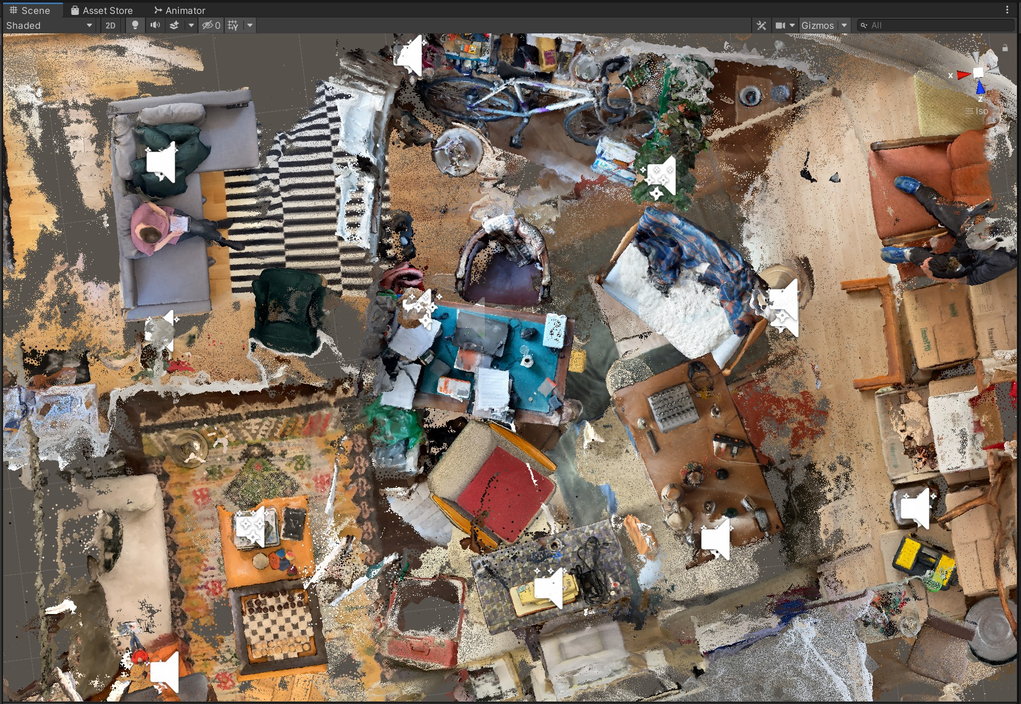

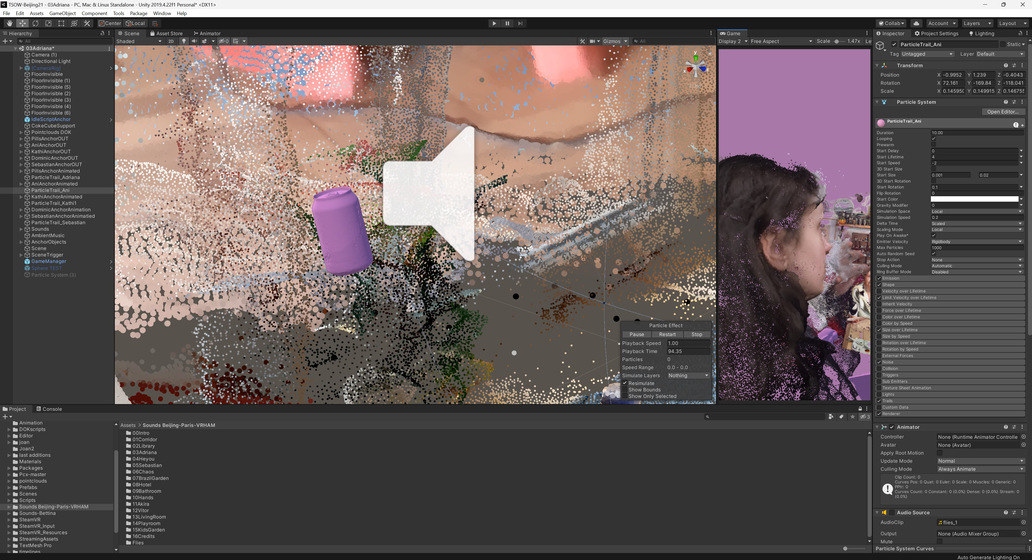

For the experimental practice of composing the material, we worked with the Unity game engine in combination with an HTC VIVE Pro headset as a spectatorial and embodied interface. Often, the process began with composing elements on the screen, followed immediately by entering the room-scale VR setup to test the spatial qualities of the designed chapters.

Practically speaking, as essayistic combiners of the material, we treated the 3D fragments and audio memos as discrete building blocks. The work of constellation was intuitive and affect-driven, guided as much by our intellectual engagement as by our sensory response. The process was shaped, too, by the bodily and spatial effects that arose from manipulating the material. We experimented extensively with varying scales, with animations and distortions, with systems of interaction, and with atmospheric effects such as the fading in and out of fragments, superimpositions, as well as with the spatialization of sound elements. These spatial gestures, in turn, were central in crafting the tone of each chapter.

For instance, one chapter dwells on the elusive and sometimes bizarre nature of dreams shared by many participants during phases of lockdowns. Here, the spatial constellation carries a particular surreal character: fragments rhythmically morph and stretch, fade in and out, and vary in scale. It was the attempt to inscribe the absurdity of many of these dreams into the fabric of the chapter’s scenography. In contrast, other chapters lean more toward a documentary mode, often focusing on a specific individual. For example, a politically driven chapter, Alban from Pristina, one of the project’s first participants, to whom we dedicated an entire chapter. The spatial composition consists of fragments from Alban’s beautiful library, where he appears seated at a desk, his back turned toward the center of the scene. There are no elaborate effects or animations at play here; instead, the chapter puts emphasis on the act of attentive listening. By moving through the library, the visitor encounters Alban’s reflections on the political tensions in Kosovo, interwoven with field recordings from civic protests that took place on private balconies in response to the government's contested policies.

In yet other chapters, seemingly documentary material intertwines with more experimental and fictional, or surreal, inflected moments.

This experimental, and being-in-close-contact-with-the-material, way of working resonates strongly with Catherine Grant’s audiovisual essayistic experiments and her insistence on an intuitive and reflexive handling of material. As she emphasizes her interest in knowledge effects that emerge precisely in the moment of working with the material, rather than following a predetermined conceptual framework or fixed hypothesis.[1]

In this context, the real-time nature of game engines such as Unity, and their potential as an experimental combinatorial device need to be briefly touched upon. Many of the ideas and decisions that eventually shaped distinct aspects of each chapter emerged through experimentation, chance, and even luck, often through the unpredictable behavior of media elements within the engine’s affordances. Letting elements collide, attaching sounds to them, scripting behaviors through code — in other words, composing interactive and interdependent scenarios from the spatial, visual, and sound materials at hand — became not only central to the process of essaying, but also one of its most intriguing and pleasurable activities.

It became a continuous, provisional rehearsal of fragments: a process of weighing, testing, and allowing them to speak for themselves and to one another. Our role as essayistic combiners thus involved both an embodied engagement with the process and a sustained critical reflection on the meanings being composed, and on the modes of mediation through which those meanings took shape. Much as Catherine Grant describes her video-editing software as a lab,[2] we conceived of the game engine as our very own experimental laboratory, a space where the actual process of essayistic thinking began and took form through the act of making.

[1] See for instance …

For a more in-depth discussion of Grant’s essayistic work see Chapter 2.5 in the thesis book.

[2] Catherine Grant, “Thinking through the Video Essay,” Tecmerin Video Essay Webinar, filmed October 1, 2021, webinar, 0:36:05, Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/620218461, accessed March 15, 2023, at 0:02:55-0:03:00.

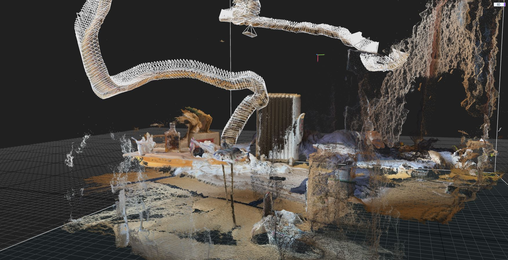

From Pixels to Clouds

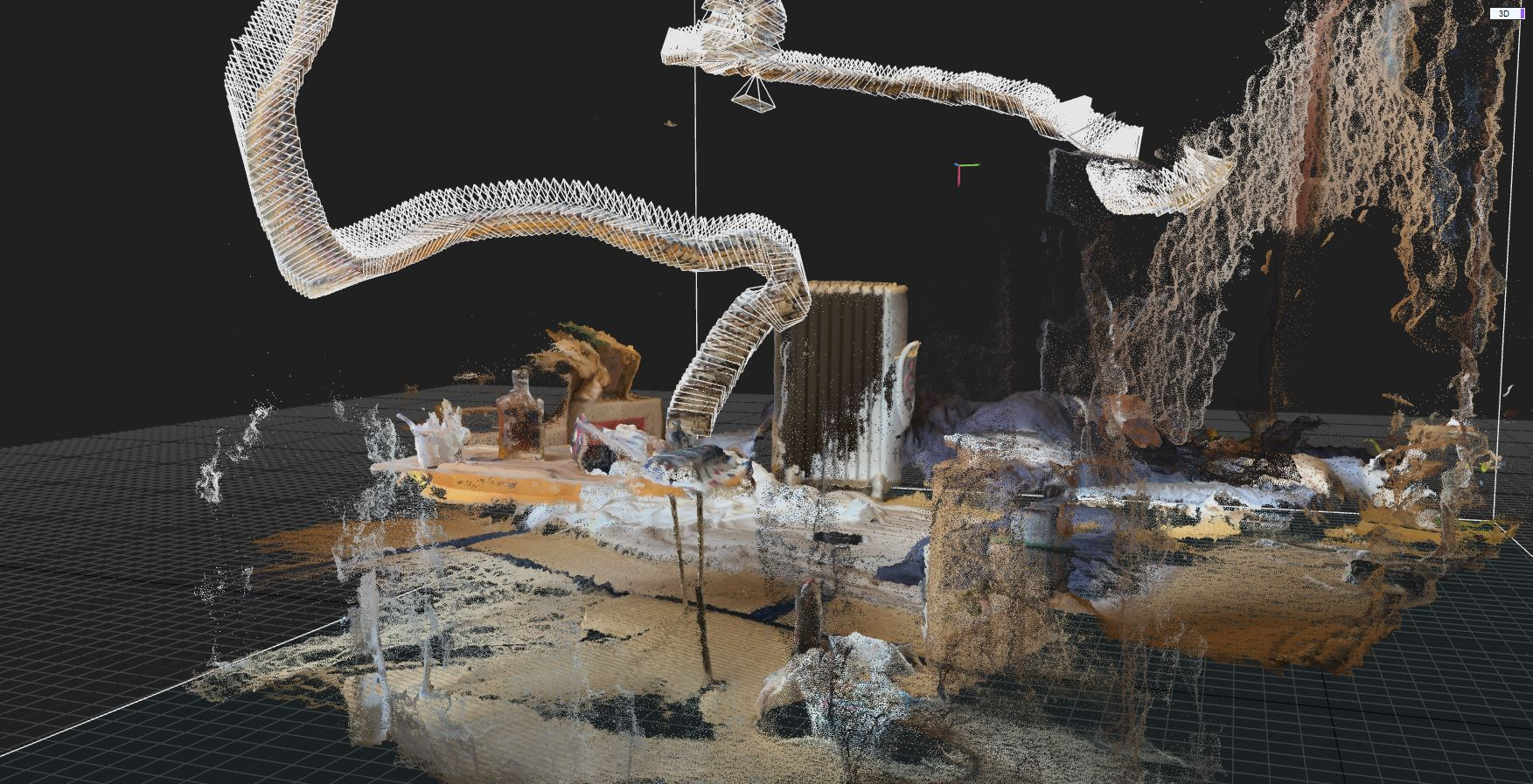

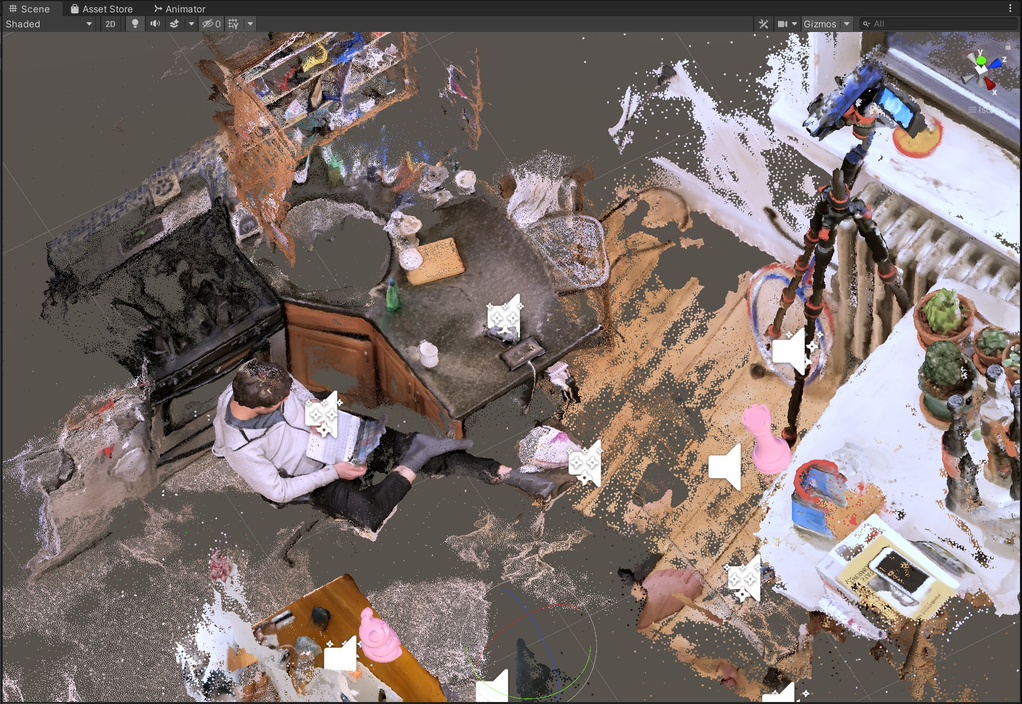

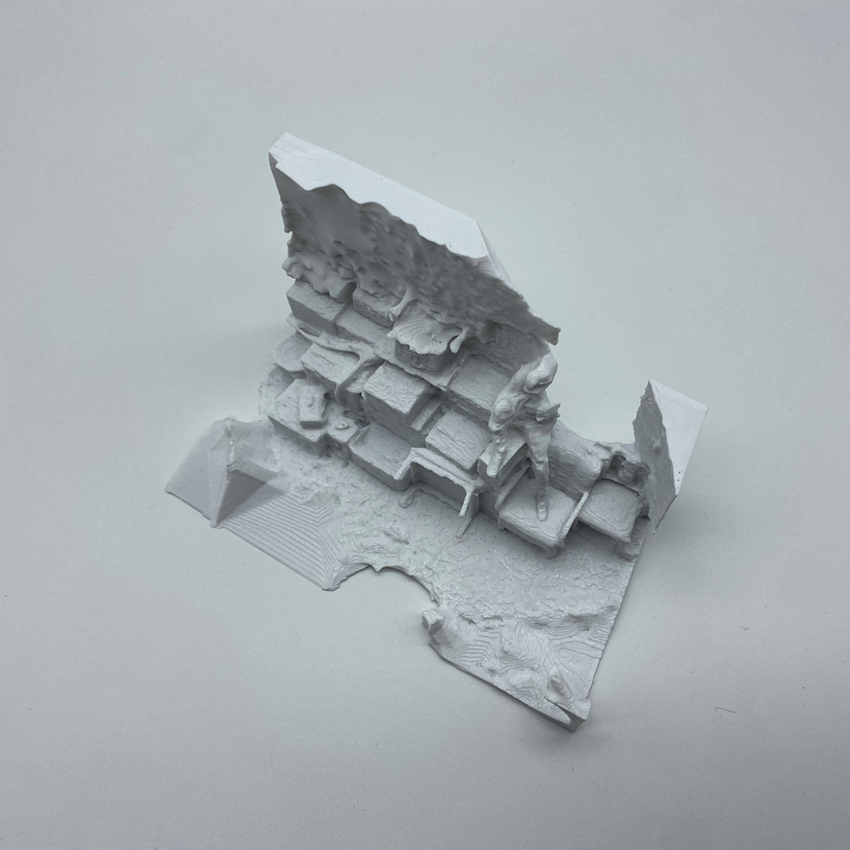

The gathered audiovisual material was subjected to further transformation. Our method was to extract a large number of still images, or frames, from each contributed video and process them through photogrammetry software to generate 3D artifacts from the contributed audiovisual footage. The quality of the source material — and, crucially, the way it was recorded, the articulation of movement in space — determined to a large extent how the spatial fragment would digitally materialize. Whether it appeared precise and coherent, or fractured, disjointed, and riddled with flaws.

In a nutshell, the method of photogrammetry is used to reconstruct 3D objects, their “[…] form, dimension and position […] by analyzing and measuring images of them.”[1] Digital photogrammetry software often makes this process of visual interpretation traceable by spatially aligning the analyzed images according to their overlapping visual features. Yet in doing so, it also produces something else, namely a remarkably detailed trace of the camera’s trajectory through space. In the context of the collected audiovisual material, what emerged is a cartography of the author’s movement, where they paused, where they lingered with greater attention, where they were suddenly affected and made an abrupt maneuver. In this sense, the entire gesture of filming is inscribed in the images themselves and subsequently materialized as a 3D object.

As discussed in Chapter 2.4 in the thesis book, these 3D artifacts occupy a peculiar threshold between a legitimate document and a fictional construct. They seem to inhabit a liminal space, and they perform their authenticity precisely because of this instability. Moving through them conveys, to a certain extent, the aura of the person who once inhabited the recorded space. I like to think of them as post-performative environments, spaces saturated with latent narratives that are only waiting to be momentarily uncovered and interpreted.

It was, therefore, significant to us that at the first public presentation of The Smallest of Worlds, at the group exhibition Les Ailleurs, at La Gaîté Lyrique, in Paris, the curatorial team and the jury, who later awarded us a Special Mention, responded to this quality directly. At the opening ceremony, the film director and jury president Cédric Klapisch praised the work as a “[…] combination of the creation of a world of fantasy – the Méliès approach — and the documentation of the real — the Lumières — and offering a very appealing window into the intimate spaces of those who participated in the work.”[2]

This oscillation between the fantasy and the documentary, highlighted by the jury, is not only evoked by the employed method of photogrammetry itself, but is, I would argue, intensified through the aesthetic choice of rendering the photogrammetric fragments not as solid artifacts, but as discrete point clouds. Traditionally, point cloud representations have been used more commonly in scientific contexts, such as heritage preservation or architectural documentation, and exactly due to their very precise visual appearance and high degree of detail, they often mediate a sense of accuracy and empirical truth.[3]

Seen from a more artistic angle, however, point clouds, in their very essence, evoke an atmosphere of incompleteness and fragmentation. To grasp their ephemeral gestalt and ambiguous articulation, many are compelled to draw on metaphors: memories, dreamscapes, afterimages, and so on. Within The Smallest of Worlds, we aimed to emphasize these qualities through various aesthetic interventions, such as experimenting with point densities and point sizes, shifting color information, or animating point clusters with subtle movements. In this very same spirit, the inconsistencies, glitches, and noise that emerged in the initial act of translation — from images to 3D data — were not treated as flaws, but embraced as forms of processual inscription, as the material’s own agency and its expressive character.[1]

Ambiguous moments also arise in the act of composition. When multiple fragments intersect, superimpose, or loosely collage, their translucent visuality often produces a restless yet stimulating field of point clusters — something maybe akin to visual white noise. From one angle, contours of figures seem to take form and momentarily declare themselves; yet with a slight shift, they seem to dissolve back into shimmering noise again. This perpetual flicker generates a recurring play of pareidolia, a continuous prompting of an active mind to interpret, to make sense, and to search for patterns.

This evocative potential, their visual instability, their tendency to drift, and their readiness to trigger interpretation became central to our visual and atmospheric approach. It enabled us to lift the work off its documentary register and to foreground its fragile and speculative constitution. However — and importantly — within these layers of artistic reworking, the work still retains an echo of its empirical origin. This ongoing destabilization of the dichotomies between the documentary and the fabulated, as well as the continual negotiation of this shifting threshold, became an essentially essayistic gesture within the visual and spatial language of the piece.

[1] Paula Redweik, “Photogrammetry,” in Sciences of Geodesy-- II: Innovations and Future Developments, ed. Guochang Xu (Springer, 2013), 133.

[2] Joan Soler-Adillon et al., “The Smallest of Worlds: Participation, Construction of Space and Micronarrative in VR-Based Experimental Documentary,” in Documentary in the Age of COVID, ed. Dafydd Sills-Jones and Pietari Kääpä, Documentary Film Cultures, volume 4 (Peter Lang, 2023), 80.

[3] Lucija Ivsic et al., “The Point Cloud Aesthetic: Defining a New Visual Language in Media Art,” Virtual Creativity 13, no. 2 (2023): 215, https://doi.org/10.1386/vcr_00085_1. CHECK AGAIN WITH THE ACTUAL PUBLICATION!!!!!!! DOWNLOAD UNI BIB COMPUTER

“Who are we, if not a combinatorial of experiences, information, books we have read, things imagined. Each life is an encyclopedia, a library, an inventory of objects, a series of styles, and everything can be constantly reshuffled and reordered in every conceivable way,” wrote Italo Calvino in his Six Memos for the Following Millennium,

https://www.faena.com/aleph/zuihitsu-the-literary-genre-in-which-the-text-can-drift-like-a-cloud#:~:text=Zuihitsu%20has%20no%20rival%20in,even%20within%20a%20volcano%20within.

“antike workes, and monstrous bodies, patched and hudled up together of diverse members, without any certaine or well ordered figure, having neither order dependencie, or proportion, but casuall and framed by chance” (quoted from Michael L. Hall p.79. In: Essays on the Essay)

“[…] an aggregate either of diverse material or disparate ways of saying the same or similar things.” (Brian Dillon)

Inscribing the Self

While in the essayistic life-writing work The Silver Screen Effect, moments of self-inscription are quite explicit and carry an autobiographical note, these moments of authorial presence are subtle and almost discreet in The Smallest of Worlds. While fragments of our own private spaces are woven into the collection, they are never explicitly marked as such. Our enunciations are instead infused in quieter ways, such as in the form of subtle voice-over commentary, where the spectator occasionally hears, in certain moments, in-between the multiplicity of participants’ testimonies, our personal interpretation of the fragmented scenes in which they are immersed. Authorial inscription also emerges through the manipulation of the material within each chapter and in the gentle forms of guidance that inform the visitor’s journey.

Although the spectator experiences the VR environment alone and in solitude, we felt a strong desire, as authors, or perhaps more fittingly, as companions, to accompany them. We always came back to the idea of metaphorically walking beside the visitor, showing the pathways through which we ourselves had most affectively encountered the material, and how we were both intellectually and sensually thinking it through. In this sense, our gentle guidance surfaces only in fleeting moments. At times, for instance, through sonic elements that would inflect the fragments with a distinct tone or atmosphere, and hence influence the visitor’s visual perception and their reading of the scene.

In other cases, our authorial presence becomes palpable through spatial navigation itself. Typically, the visitor is free to move through the environment. Yet in certain moments, we would intervene, by blocking the free movement, redirecting their gaze, or slowing the pace, so that a scene must be encountered from a specific angle, or discovered at a deliberate tempo. These interventions are important, yet I would not consider them as dominant and didactic gestures, but rather as suggestions to inhabit moments of distinct ways of seeing and feeling the composed scene, ways we ourselves found most vital in the act of creation.

However, beyond this subtle guidance, visitors are encouraged to explore each chapter within the VR piece on their own terms, to form their own associations and connections with the material presented. This openness is essential not only for establishing an essayistic dialogue and inviting the visitor to think with us through the material, but also because the work most probably resonates with each spectator on a very personal level. Almost every person has, in some way, experienced the conditions of pandemic lockdown and has developed, within this state of crisis, a personal understanding of what it means to claim a private space — in both senses, within the intimacy of their own life and in relation to the broader global situation affected by the pandemic.

Waking in Circles: The Smallest of Worlds Archive

After translating the first wave of the contributed audiovisual material into 3D point cloud fragments, we increasingly turned our attention to the question of how this growing collection, or emerging archive, might be made accessible.

What was clear to us from the very beginning was that we wanted to conceive a VR experience through which the material could be encountered. We felt that the intimacy of the medium, its spatial nature, and its capacity to situate the visitor inside the material offered the most affective way of negotiating and accessing it. Yet, this decision naturally raised a new bundle of questions: how should such an encounter be composed? Importantly, in what ways could it become essayistic? And, from both a conceptual and practical angle, how can the work stay structurally open, or, put differently, how can it remain receptive to the potential of a gradual implementation of new material that continued to reach us through our webpage and the call for participation?

Inspired by Chris Marker’s Roseware (1998-99) and Immemory One (1996-97), we began to imagine the essayistic experience of the archive as an assemblage of chapters that could be approached and traversed in a nonlinear manner. Thinking in discrete chapters, as modular units, or as bits and pieces in a gradually expanding mosaic, seemed productive, since it offered an open framework that allowed for the flexibility to re-curate content or to add newly received material to the constellation without affecting the whole. Just as importantly, it felt necessary to make this condition, the ongoing process of the work, perceptible within the very structure of it. Conceptually, we thought that the archive should not present itself as something that could be grasped and consumed in a single VR session. Instead, we felt, it should announce — yet in a subtle way — its own incompleteness. Interfacing with the archive through the VR experience would thus always reveal only a partial view, and it would be through repeated returns that a visitor might gradually gather a sense of its scope, its density, and its evolving nature.

Zooming in on the level of the chapter itself, each one was composed of one or several photogrammetric fragments, accompanied by a plurivocal composition of voice-over commentary and a corresponding soundscape. More than being organized simply around themes, the chapters were curated through atmospheres, moods, tonalities, and affective registers. Some chapters incline toward the melancholic, others pulse with a more positive mood; some drift into the surreal or ironic, some lean toward a documentary approach; a few drown in dreamlike memories, while others carry a distinct political and activist charge.[1] Yet, all of them sought, in their own manner, to grasp an essential dimension of the central subject: the role of private space under indeterminate conditions of an unfolding global pandemic.

In an essayistic manner, the constellation of chapters can be understood as an array of attempts circling around their subject, akin to what Silvia Henke et. al. describe as the continuous “walking in circles,”[2] the repeated exercise of essayistic thinking attempting to carve out unique forms of knowledge about its object. In this sense, each chapter thus offers another perspective on the overarching inquiry, without seeking to exhaust it or try to reach a resolution. Rather, each remains an open-ended attempt to engage with it, to probe it, and to question it thoroughly.

[1] Joan Soler-Adillon et al., “The Smallest of Worlds: Participation, Construction of Space and Micronarrative in VR-Based Experimental Documentary,” in Documentary in the Age of COVID, ed. Dafydd Sills-Jones and Pietari Kääpä, Documentary Film Cultures, volume 4 (Peter Lang, 2023), 71.

[2] Silvia Henke et al., Manifesto of Artistic Research: A Defense Against Its Advocates, Think Art (Diaphanes, 2020)., 34.

Meandering between Chapters

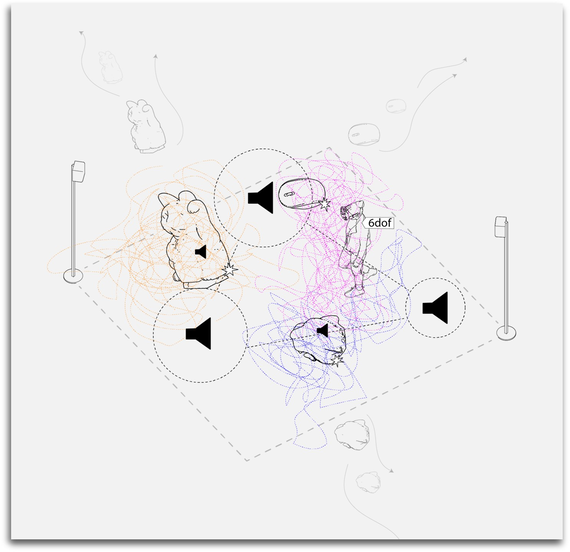

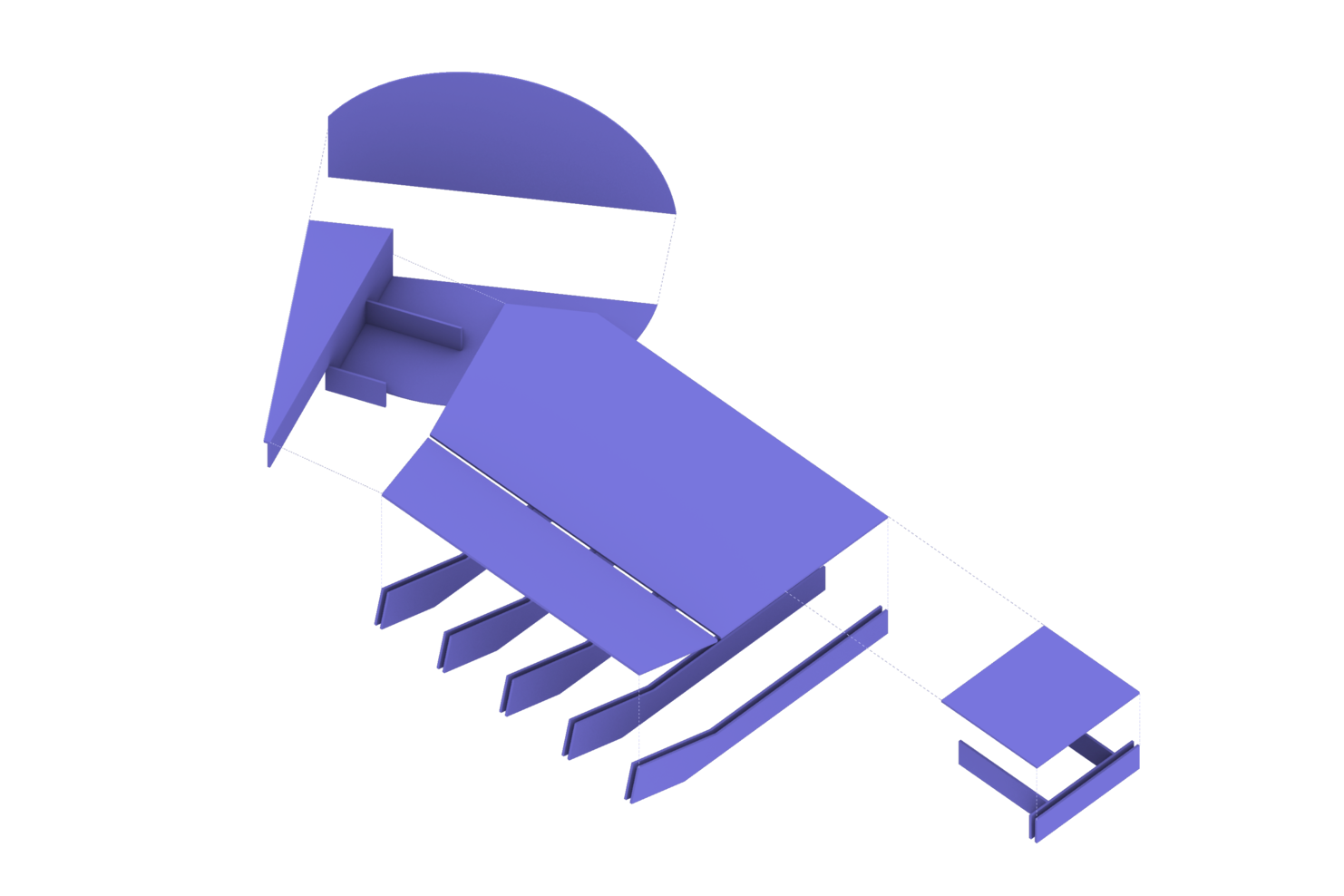

Zooming out to consider the composition of the chapters themselves, we aimed to design a nonlinear mode of navigation.

The idea was that every visitor would begin and conclude their journey with the same chapter, yet the sequence in between would unfold differently for each individual experience. In this way, every traversal through the work becomes a personal digression, a constellation of encounters shaped by the visitor’s own intuitive choices.

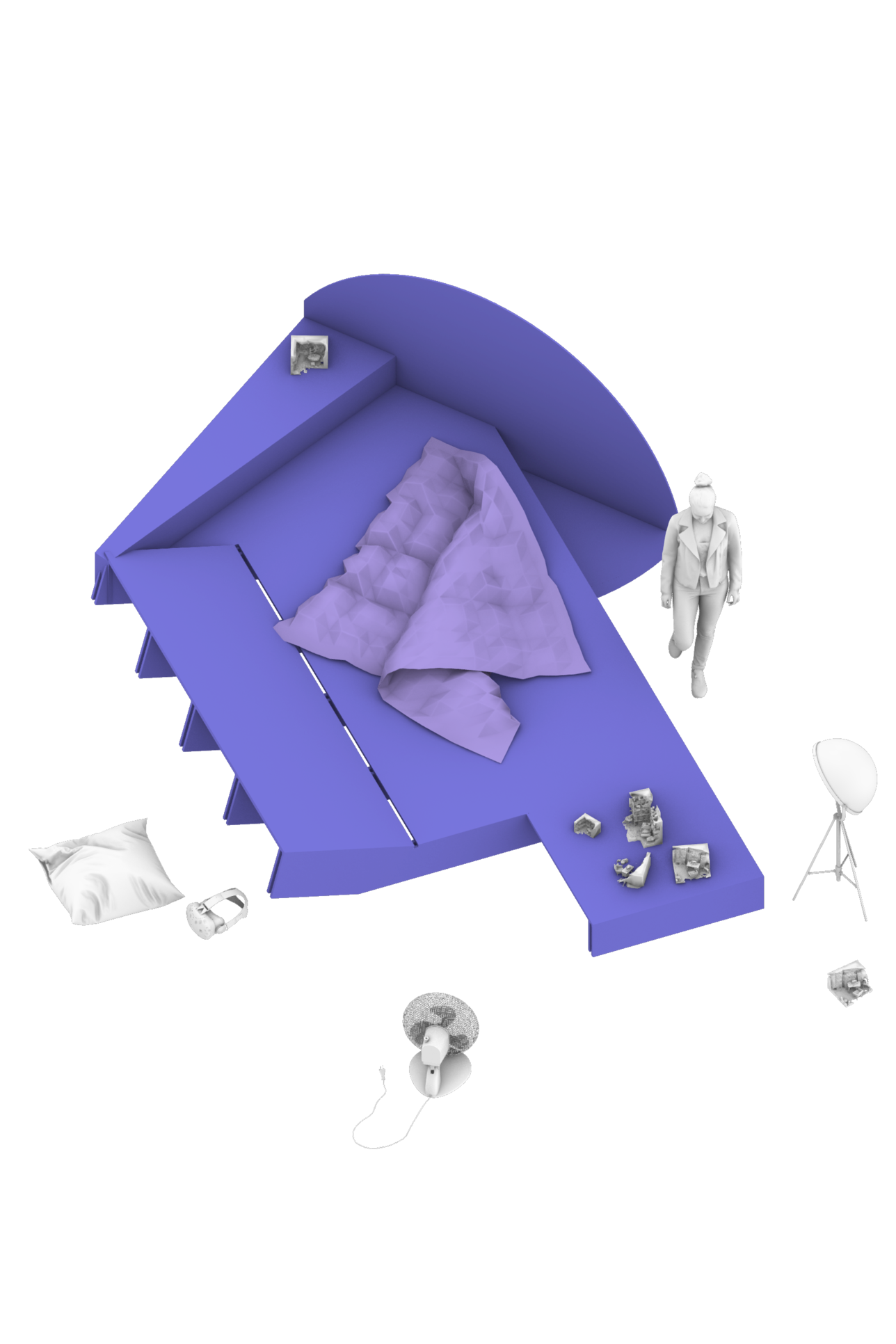

Every chapter is time-based. Once the designated time for that chapter elapses, all elements previously activated by the visitor gradually fade away. In their place, three miniature domestic spaces emerge. The visitor may then select one of these miniatures and is subsequently transported to the corresponding next chapter. This navigation principle between the chapters repeats throughout the experience.

Although each path taken forms an individual journey, the available options to choose the sequel chapters are every time carefully rearranged to establish an underlying rhythmic balance. This was necessary to ensure that no visitor passes through a series of chapters with identical moods, atmospheres, or tonalities. Across the experience, each visitor moves through a total of eleven chapters. On average, a full walkthrough lasts approximately twenty minutes.

Through many conversations with visitors after they experienced the VR piece, we understood that there was a recurring desire for more time to linger within each chapter, to dwell more deeply in its content. While we were aware that the density of material might feel for many overwhelming, we had, as already noted, intentionally aimed to create a sense of partiality and incompleteness as part of the essayistic experience. From the very beginning, the work was conceived as something that could not be fully grasped in a single sitting, rather as an archive that would unfold gradually, by visitors returning once or even a second or third time.

Yet the realities of exhibition practice, with strict time slots, visitor turnover, and the exclusive nature of the VR setup, made this ideal difficult to achieve. These are aspects that will need to be reconsidered, especially within gallery contexts. At the same time, as many visitors told us, these very constraints turned out to be generative, yet in a rather unexpected way. Since each visitor could only encounter a partial constellation of chapters, the work continued beyond the headset, namely into conversations, into sharing and comparing of experiences among visitors afterwards. It became a collective act of piecing together a larger narrative from individual encounters, and as such, it fostered another form of public dialogue. This realization highlights the importance of the offboarding process, of establishing within the conventions of the gallery a place for meaningful post-experience gatherings that encourage discussion and personal exchange.

“Now we are in a position to see that it offers aesthetic knowledge, that is to say knowledge which is organized artistically rather than scientifically or logically. The essay’s open-minded approach to experience is balanced by aesthetic pattern and closure. It is not a work of art in the full sense, but a kind of hybrid of art and science, an aesthetic treatment of material that could otherwise be studied scientifically or systematically.” (Graham Good p 14-15)

Interaction as Unspoken Collaboration

Another crucial element that shapes the encounter between the audience and the collected material is the project’s interaction design.

Each chapter is built around the principle of active exploration. Our idea was simple: we wanted visitors to navigate the space as freely as possible, engaging with objects that, when interacted with through touch, would trigger an event, such as the unfolding of spatial fragments, the emergence of voices, or sonic layers. In this sense, each chapter would gradually build and intensify through the visitor’s participation.

For the visual representation of these interactive objects, we used everyday items that we extracted from the captured interior fragments we collected. The interactive objects are scattered across each chapter in order to prompt the visitor to become active, to actively move through the digital space. We really aimed for a simple and intuitive interaction system, one that would be accessible even to those who are not familiar with video game conventions.

Within each chapter, we leave the decision to each visitor whether they carefully activate one element after another, listening attentively to each voice and move slowly from fragment to fragment, or whether they allow themselves to be overwhelmed, triggering multiple layers simultaneously and immersing in a dense, chaotic weave of overlapping spaces, voices, and sounds. In both cases, the visitor is essentially urged to become a combiner, a co-author in the unfolding of the work.

Each chapter is intentionally designed to make it impossible to activate all elements, and at the same time, listen to every single voice, or inspect every spatial fragment in one session. This deliberate sense of partiality and incompleteness is central to the experience. Visitors are confronted with the feeling that they are missing something, that the narrative remains elusive, and resists closure. The experience thus demands an active interpretive effort, visitors are asked to fill in the gaps and to assemble their own constellations of meaning.

In other words, the essayistic experience does not exist independently of the spectator. Its open structure depends on the visitor’s active investment, namely in their willingness to actually animate the digital space and through their active participation in the ongoing construction of meaning. In this way, the interaction design enacts another dimension in the dialogical nature of the work.

During the various exhibitions of the VR experience, we began to notice some recurring patterns in how visitors interacted with the work. While most visitors intuitively grasped the interaction system built on exploration and reflection, there have nevertheless been two extreme tendencies that stood out.

On the one end, visitors familiar with video games often rushed to interact with everything at once. Conditioned by conventional gameplay logic, they tended to approach the piece as something to be completed rather than to attentively inhabit. As a result, the reflective, essayistic mode we had envisioned often gave way to a kind of frantic activation, which left little room for contemplative engagement.

On the other end, visitors with no gaming experience sometimes felt lost. A few wandered through the digital space without realizing that content needed to be activated. Although these cases were rare, they showed the need for a minimal introduction.

These contrasts prompted us to think more critically about the balance between agency and guidance in immersive works. Freedom of exploration presupposes a certain sensitivity to both the content and its structures of interaction. To foster this sensitivity, a brief introduction during the onboarding process — just enough to orient without prescribing the experience — felt the most effective approach.

Participation and Risky Accounts

There is an inherent uncertainty inscribed in this kind of participatory process. One can never fully anticipate how the process will turn out, or what kind of material — if any — will arrive. Yet it is precisely this uncertainty and contingency that, to a certain extent, give the endeavor its particular appeal. The unpredictability manifests not only at the level of the content received — the captured scenes or recorded voices — but also within the materiality of the audiovisual documents themselves.

Undoubtedly, the received documents during the gathering phase are marked by a broad spectrum of heterogeneity. On one level, this diversity stems from the varying qualities of smartphone cameras used, the lighting conditions of the recorded environments, the formats and resolutions of the files submitted, as well as the differing audio qualities of the devices, and the presence of ambient noise, among many other such factors. On another level, diversity is inscribed in the particular ways in which the cameras were handled: at times with smooth and careful movements through space; at other times with abrupt and fragmented gestures. Some recordings are punctuated by sudden turns of perspective, while others unfold in a more steady and continuous rhythm.

We intentionally chose not to prescribe strict guidelines for how participants should record their surroundings or the moments they wished to capture, nor did we specify formats, resolutions, or file types. Although we provided a loose guiding video on the project website that showed fragments of a person filming a portion of their space — we felt this was a necessary minimal gesture to orient the prospective participants. It was crucial for us, both conceptually and experimentally, that the resulting contributions would diverge from one another rather than forming a uniform and streamlined collection of audiovisual fragments. For this reason, we also accepted the fact that some submissions, due to their material quality, would be challenging to work with in later stages of the project.

“I do not speak the minds of others except to speak my own mind better.” 1

“I know not any where the book that seems less written. It is the language of conversation transferred to a book. Cut these words, and they would bleed; they are vascular and alive.” 2

What is the Meaning of Private Space in Times of Crisis?

The Smallest of Worlds began with a simple yet profound question: What is the meaning of private and intimate space in times of pandemic crisis?

This question grew suddenly, and urgently, resonant as the domestic sphere became, almost overnight, the inevitable center stage for work, socialization, and public life, forced by a condition that — without comparable precedents — had blurred the boundaries between public and private life, exterior and interior.

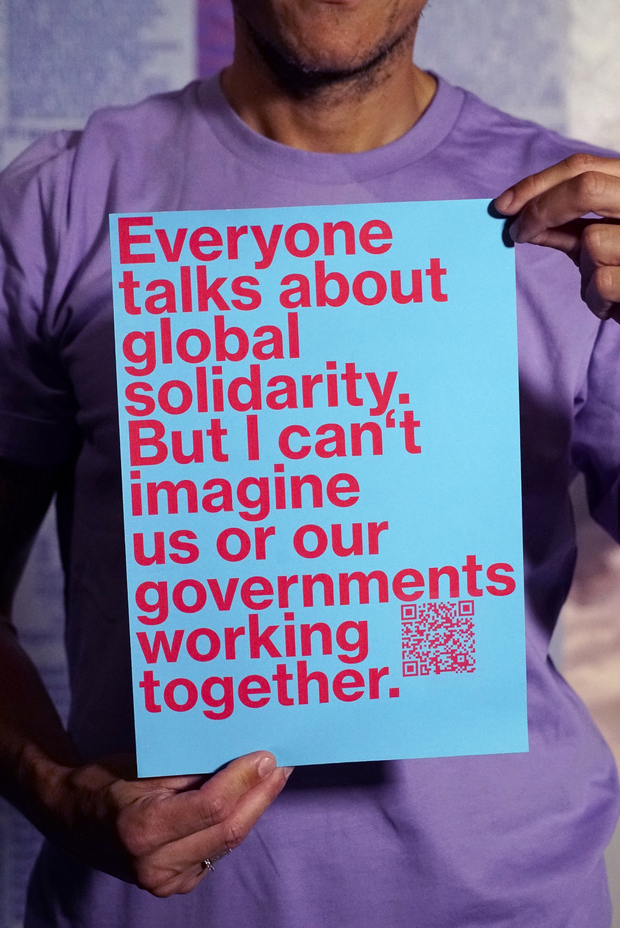

Against this backdrop, we began by reaching out, first to those closest to us, like family members and friends, inviting them to participate in the project. We asked them to record a short, one-minute video of a portion of space in their homes that had helped them cope with the situation of the pandemic. Accompanied by a voice memo — spoken while filming — that would address the project's guiding question: the meaning of the private and intimate space in times of pandemic crisis, whether from a personal perspective or more general stance.

After this initial phase, and quite encouraged by the depth and sheer diversity of these responses, we decided to launch a public webpage to extend our outreach to a broader and more diverse audience. The layout of the site was intentionally simple. It posed the same core question and provided an upload field for users to drop their responses as a video file. Additionally, underneath, there was a text field to optionally answer three more follow-up questions: What was going through your mind at the time of quarantine? Did it change the view of your home? And how, do you think, it impacted your surroundings?

Finally, we asked for some minimal personal information. In order to ensure privacy for all contributors and their responses, we only asked for the first name and the city of residence. However, if they wished to follow along with the project’s development or to maintain an ongoing dialogue with us they could also leave an email address. Yet, importantly, none of this additional information was mandatory; participants could, of course, remain fully anonymous if they preferred to.

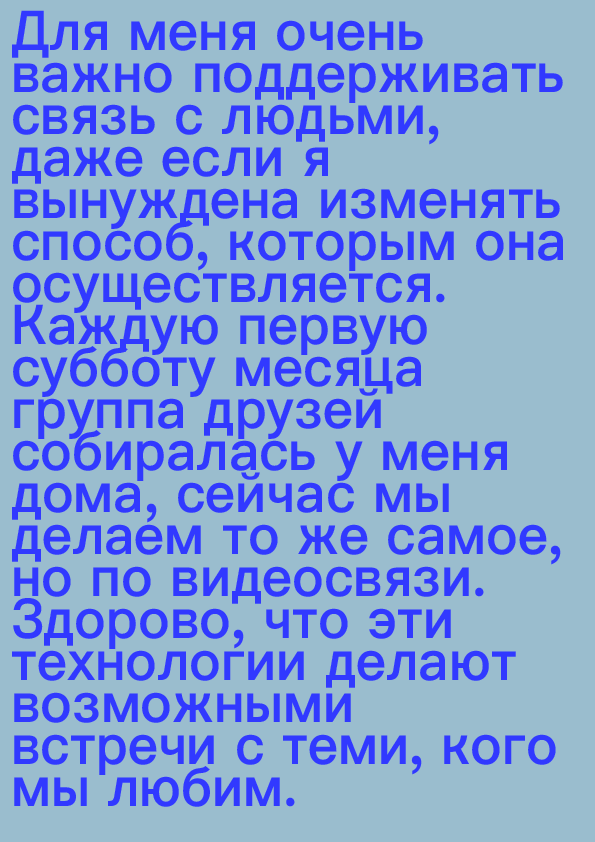

The webpage remained active for about eighteen months. During this time we received hundreds of contributions from participants across more than forty countries. This collection constitutes an intriguing, polyphonic portrait of how individuals around the world grappled with the shifting meaning of private space during a period of such profound uncertainty. Together, these contributions offer a situative mosaic of stories, voices, and reflective thoughts, capturing both the intimate texture of everyday life and the unsettled condition of the domestic sphere at large, in a moment when we were all strangely isolated yet bound together by a shared global experience.

The breadth of material we received was strikingly diverse. While the biggest quantity of submissions still came from Western Europe, a significant number of contributions reached us from many other corners of the world, such as Egypt, Japan, Brazil, the United States, Kosovo, China, India, South Africa, etc.[1] Similar to the geographical span, the short videos reveal a wide array of domestic scenes: kitchens, living rooms, attics, libraries, bedrooms, balconies, gardens, storage spaces, hotel rooms, garages, etc. Some videos are inhabited by people, others are mainly occupied by things. Certain places appear carefully staged, as if arranged for the purpose of the camera lens, while others feel like an unfiltered, authentic glimpse into the intimacy of an ordinary domestic setting. The accompanying audio testimonies are predominantly in English, though there are many other languages scattered throughout the collection: French, Arabic, Turkish, Mandarin, German, Swiss German, Russian, Spanish, Catalan, and more.[2]

What we became more and more aware of, in the process of collecting, was that the project, at this phase, did not merely serve as an archive to capture and document a historical moment. It gradually began to form the contours of a space, possibly even a safe space, for expression and, perhaps, even for relief. For many participants, it became a place to voice their emotional and psychological states, to release their heavy thoughts, fears, and hopes that had accumulated amid the unfolding of a world that felt ever more uncertain and unstable.

Spread the Call!

Particularly during the first phase of the collection process, but indeed throughout the entire project, we received invaluable support from several institutions that not only helped us to further develop the project but, crucially at this initial phase, provided it with a certain exposure and wider visibility that proved essential for expanding its participatory reach. Among them was the VRHAM! Festival in Hamburg, one of the first to see the value in the project, invited us to join its online residency program, which included mentorship and a public presentation. Another immensely important support came from CPH:LAB, the development initiative of the CPH:DOX Festival, which accompanied us over the course of a whole year, offering tremendous guidance across many dimensions of the project’s conceptual development and outreach strategies. Finally, The Smallest of Worlds also benefited from the Pixel, Bytes + Film funding program by the BMWKMS, as well as the workshop series organized by sound:frame.

[1] Joan Soler-Adillon et al., “The Smallest of Worlds: Participation, Construction of Space and Micronarrative in VR-Based Experimental Documentary,” in Documentary in the Age of COVID, ed. Dafydd Sills-Jones and Pietari Kääpä, Documentary Film Cultures, volume 4 (Peter Lang, 2023), 68.

[1] Ibid.

Prelude

The idea for the project The Smallest of Worlds was born in February 2020. I got selected to join a media art residency at Espronceda, Institute of Art and Culture in Barcelona. It was there that I met Bettina Katja Lange, a stage designer and video artist from Berlin, and Joan Soler-Adillon, a media artist and scholar based in Barcelona. Together, we collaborated within the framework of the four-week residency and realized a VR experience which we titled Occultation. In its most basic sense, the work is a spatial recollection of our encounter with the city of Barcelona and the people we met during the time of the residency.

Occultation became, in many ways, the conceptual starting point for The Smallest of Worlds. Particularly its methodical approach, the usage of techniques such as photogrammetry, its spatially fragmented structure, the distinct visual aesthetics, as well as the interdisciplinary collaboration between the three of us, laid the groundwork for what would follow.

Shortly after the residency’s final exhibition, where we showcased Occultation, many parts of Europe began with their first wave of Covid-19-related lockdowns. Back in our home cities, and to a certain extent confined within our apartments, we continued our conversations online about the possible continuation of our collaboration — and it was precisely within this situation and under these strange global conditions, that we began to contemplate on how the pandemic crisis, unfolding in front of us, was already affecting and even reshuffling our longstanding notions of privacy and intimacy that we have built in relation to the places we inhabit and call our own. The question of what the/a private space means in times of pervasive crisis, in all its layers and contradictions, soon became our central concern, and ultimately, the point of departure for The Smallest of Worlds.

“The essayist’s aesthetic is that of the collector, or the ‘amateur’ in an archaic sense: such works seem destined for the writerly equivalent of the Wunderkammer - the essayist thrives on miscellanea. Except to say: the discrete essay may itself be an omnium-gahterum.” 3

“[…] an aggregate either of diverse material or disparate ways of saying the same or similar things.” 4

“[…] somewhere or other the spirit of essay-writing is walking on; and no one knows where it will turn up.” (Hamburger, Michael: An Essay on th Essay)

“Das Essay erklärt nicht sein Thema und informiert in diesem Sinn nicht, seine Leser. Im Gegenteil, es verwandelt sein Thema in ein Rätsel. Es verwickelt sich im Thema und verwickelt seine Leser darin. Das ist seine Attraktion.” (Flusser, P.3)

Micro-Gesturing as Self-Inscription

One aspect that became particularly interesting through the continuous review of the submitted material is the ways in which people chose to present themselves visually. Sometimes explicitly as a carefully staged character within their own domestic setting (this most probably meant that someone else must have taken the video), at other times only by a fleeting second through the appearance of their gestalt in the reflection of a mirror or window. However, another form of inscription, perhaps unnoticed by many of the contributors, is their inscription through the navigation of their smartphone camera, in the gestures of moving through their space while recording. These movements are often charged with affective moments, when, for instance, someone suddenly notices something and turns the camera to capture it. Sometimes these ruptures are rhythmic, at other times quick and uncoordinated. These gestures, in a further instance, also reveal how bodily motion becomes attuned to the act of thinking and verbalizing these thoughts: how it shifts when articulating something complex, or when expressing fear or hope, or when the mind begins to digress and wander, literally carrying the camera along with it. This reciprocity between thinking and bodily gesturing constitutes a subtle yet deeply intimate mode of authorial inscription, one that became particularly fascinating to me, as it yields yet another dimension of immediacy and interiority within the audiovisual fabric.

This performative triangle of filming, thinking, and articulating led me to revisit Alexandre Astruc’s concept of the caméra-stylo (camera-pen), which I touched upon in Chapter 2.1. — a notion of writing audiovisually, with the camera as both an instrument of thought and expression.[1] In this sense, I began to think of these audiovisual testimonies, gathered through our call for participation, as micro-essays in their own right, each portraying an inner landscape in a double sense: as a literal unfolding motion through interior spaces, and as a laying bare of an inner emotional and mental state.

[1] Alexandre Astruc, “The Birth of a New Avant Garde: La Caméra-Stylo,” in Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology, ed. Scott MacKenzie (University of California Press, 2014), 604-5.

"The essay and the essay film do not create new forms of experimentation, realism, or narrative; they rethink existing ones as a dialogue of ideas” (Timothy Corrigan, The Essay Film: From Montaigne, after Marker (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). P.51.)

“Now we are in a position to see that it offers aesthetic knowledge, that is to say knowledge which is organized artistically rather than scientifically or logically. The essay’s open-minded approach to experience is balanced by aesthetic pattern and closure. It is not a work of art in the full sense, but a kind of hybrid of art and science, an aesthetic treatment of material that could otherwise be studied scientifically or systematically.” (Graham Good p 14-15)

“It feels perfectly at ease quoting, plundering, hijacking, and reordering what is already there and established to serve its purpose. And it feels perfectly at ease doing that twice or three times over, so that the same elements switch into new configurations. It is the rhizomatic form par excellence, forever expanding and finding no better reason to stop than the exhaustion of its own animating energy.” (Jean-Pierre Gorin: Essays on the essay film p. 272)

“The essay offers knowledge of the moment, not more. The moment is one of insight, where self and object reciprocally clarify and define each other.” (Graham Good p 8)

The Living Archive

The Smallest of Worlds has been exhibited internationally across various gallery spaces and conferences. Throughout the process, we kept referring to the VR experience and its underlying archive of contributions as The Smallest of Worlds. However, for its different modes of presentation and exhibition, we began to title it #See You At Home – The Private Space as Public Encounter.

The phase of making public proved particularly interesting in this project, not only because the constellation of its content was continuously adapted and expanded as we kept collecting new material from participants, but also because the very format of the work remained essentially fluid. Each exhibition setup was articulated differently and emphasized distinct aspects and concerns of the collected material. In this sense, the work itself became a kind of living archive that would constantly reconfiguring its own form of presentation in response to new contexts, materials, and audiences.

CPH:DOX Interactive: A Protean Form in Times of Crisis

In 2020, The Smallest of Worlds, still in its conceptual phase, was invited to take part in the CPH:LAB program, a development initiative of the CPH:DOX documentary festival in Copenhagen. The program describes itself as a talent development program and playful laboratory to seek for “[…] new visions of what a documentary can be in a digital age.”[1] The plan, at that point, was that the work would eventually be exhibited physically as a result of this program and during the documentary film festival in Copenhagen in April 2021. Yet in the midst of pandemic restrictions, the very possibility of presenting a VR piece in a public exhibition setting was uncertain.

While the VR format was always at the heart of the project, we were urged to imagine alternative strategies for presentation in a public and physical context. The challenge for us laid in how to convey the character of a work designed for an immersive and intimate spectatorial experience, while ensuring it remained COVID-safe? Or put differently, how could one preserve the essence of an experience so deeply tied to intimate technology — in our case VR — without relying on VR headsets that, at the time, were regarded as problematic devices due to the high potential viral transmission?

To keep all options open, we ultimately came to conceive the project as a triptych: three distinct, yet interrelated modes of presentation that could either stand independently or could be combined into one single exhibition constellation.[2]

The first mode remained closest to our initial intention: a room-scale VR prototype, published on the video game platform Steam, for the duration of the festival. This version allowed viewers equipped with the necessary immersive technology to enter the work from the comfort of their own homes. We also thought of this setup as particularly fitting for an embodied spectatorial experience, since the viewer’s domestic environment would, conceptually, enter the constellation and form a dialogue with the domestic scenarios encountered within the work. In this way, the boundaries between the spectator’s real home and the virtual homes presented in the piece became porous.

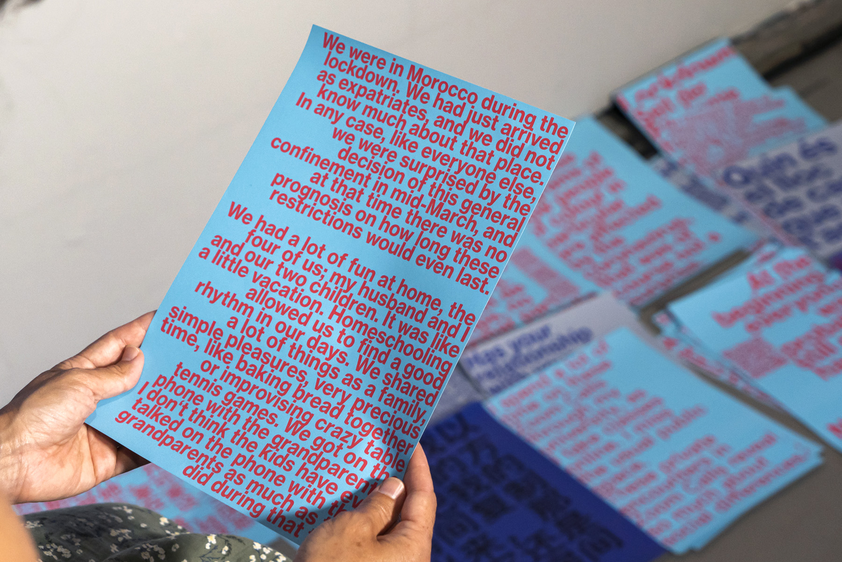

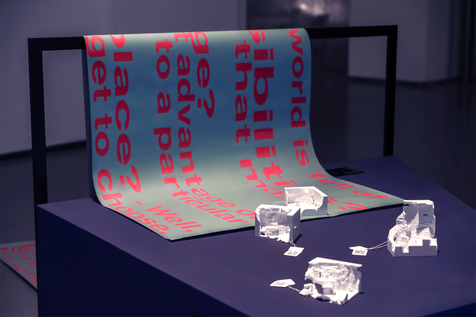

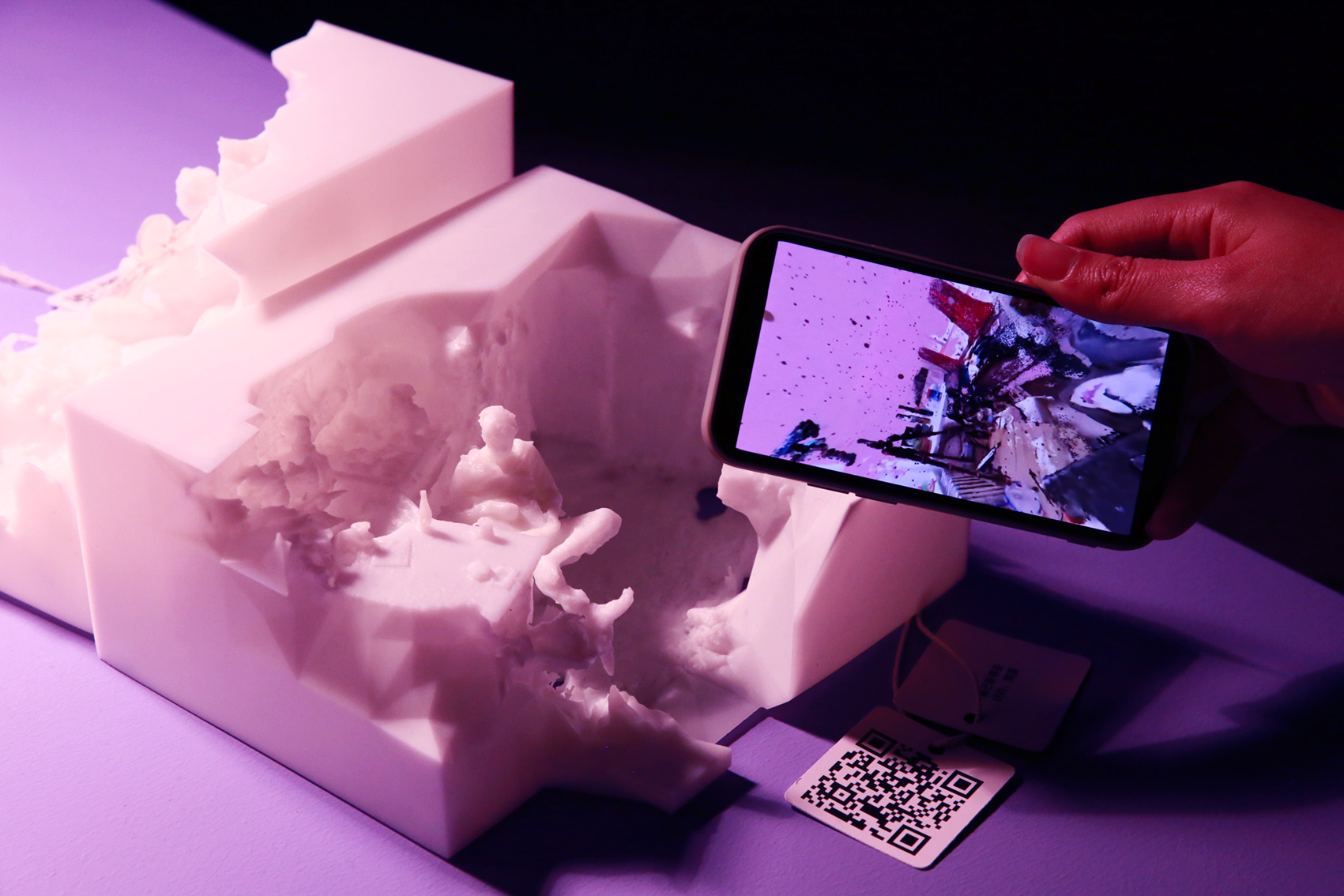

The second mode translated the digital archive into a physical form. Nine fragments were selected and transformed into 3D-printed sculptures, each accompanied by a small tag. These tags carried metadata, including the first name and the city of the contributor, and a QR code. When scanned with one’s personal smart device, the QR code opened a 360-degree interactive video, a window into the digital archive of domestic scenarios, complemented with an audio memo, and the corresponding soundscape.

While at the moment of conceptualizing and producing this second presentation mode of the work, the CPH:DOX Festival was still planned to be happening physically in Copenhagen, albeit under conditions marked by heightened awareness of health risks and strict safety measures. We regarded this version as an ideal answer to the circumstances, as it allowed visitors to engage individually, using their own devices, without the risks inherent by sharing VR equipment or being in close physical contact with others. At the same time, it addressed a broader issue, namely the inherent exclusivity of VR experiences, which are often constrained to a single or a small group of viewers at a time and thus tend to produce often long waiting lines.

However, as the opening of the CPH:DOX Festival in April 2021 approached, the organizers decided at relatively short notice to move the entire event online. This shift prompted us to once again rethink the presentation of the work and we developed a third version. The premise was to create an experience that would remain conceptually comparable to the VR piece, yet one that would offer a broader accessibility and could be encountered with a comparable low technical threshold.

This idea materialized as a screen-based web experience, launched and hosted on the indie video game platform itch.io. The presentation allowed viewers to navigate spatially and at their own pace through an entirely new composed landscape of 3D fragments and audible traces — a miniature reimagining of the VR work.

Taken together, these three iterations, or better, windows into The Smallest of Worlds archive were never meant as mere technical variations or purely pragmatic adaptations. Although the extraordinary circumstances of this particular time, amid the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, prompted our experimentation with different modes of presentation, each version was designed to reveal a distinct facet of the underlying archive of 3D fragments and audio memos, each a different inflection of the same question. In this sense, the work may be thought of as inherently transmedial: not a single fixed form, but a shifting practice of articulation, in which each medium discloses something the others cannot. Perhaps, it is here, that the project not only reflects the transgressive and protean nature of the essay, but with its historical moment, when the pandemic not only reconfigured private space but also demanded new, experimental modes to exhibition and spectatorship.[3]

#See You At Home: Curating between Beijing / Zurich / Barcelona — Materializing the Immersive Archive

During 2021 and 2022, we conceptualized and realized three major exhibitions to present the project and growing archive of The Smallest of Worlds. Each exhibition carried the title #See You At Home — The Domestic Space as Public Encounter and unfolded as a distinct iteration of the project. The first took place at ETH Zürich, invited by the Chair of Art and Architecture led by Prof. Karin Sander; the second at the Goethe-Institut China in Beijing, in their gallery space 798; and the third at the Santa Monica Art Center, as part of the ISEA conference in Barcelona.

Although all three shared the same title, each exhibition constituted a re-curation of the collected material, with an emphasis on different aspects of the work. At the core of every presentation remained the VR experience, which functioned as the nucleus around which other elements were choreographed. These elements included the already briefly discussed 3D-printed miniatures derived from a selection of contributed spaces, visual and textual excerpts from translated video submissions and transcribed testimonies, carefully chosen found objects that echoed atmospheres from the received domestic scenarios, and a display design that wove these disparate fragments into a cohesive constellation that invited the gallery visitors to encounter the work in multiple ways: through touch, reading, listening, or through full bodily immersion.

At the Goethe-Institut gallery space 798 in the Art District of Beijing, we extended this constellation with a live projection, a window into the Mozilla Hubs environment composed of fragments collected in preparation for the lecture performance (see section on the lecture performance, as well as the reflection on the Mozilla Hubs room). In Barcelona, at ISEA conference, we expanded the installation with monitors displaying raw, unedited footage from the archive, thereby opening another register of engagement, a more transparent view into the collection itself.

Each of these exhibition environments was conceived not as a neutral display but as a place, or more precisely, as a site of exchange. A spatial composition that evoked, however abstractly, the qualities of a domestic space, while being situated within the ambiguous terrain between the notion of intimacy and interiority (which resides at the project’s core), and the public domain of the gallery space.

The spatial concept of each exhibition was guided by the twin gestures of wandering and pondering. Much like the VR experience, the exhibition setups were designed as explorative environments in which visitors could linger, interact with the artifacts, make themselves comfortable, and gradually unfold the constellation of materials at their own pace and rhythm. Presenting the work in a fragmented manner spatially and narratively, and without a definitive line of argumentative thought, was for us not simply a curatorial decision, but an essential strategy for creating a dialogical space, one that invited the visitor to piece together the fragments, to think with us (the authors) in the reverberation of the presented materials, to hesitate, to question, and if it is felt, to doubt, or even to disagree with our thoughts and opinions. Essentially, they are asked to become interlocutors, active agents to construct meaning across the presented artifacts according to their own terms of engagement.

This approach echoes the notion of meandering and straying discussed in Chapter 4.2 of the dissertation Book: a refusal of linearity and prescribed pathways. None of the exhibitions had a fixed direction, a correct route to follow, or even a designated starting point. Instead, they where presented as an open and unstable spatial text. Each visitor was prompted to find their own way through the assemblage. They were encouraged to drift, to digress, to lose themselves in the multiplicity of materials and the stratified media layers. In this sense, the exhibitions were conceived less as didactic displays than as landscapes, open terrains of fragments — coordinated rather than subordinated[1] — to be discovered, traversed, and meticulously inspected. The act of wandering through them became both a mode of encounter and a method of knowledge generation, in a sense of a slow, tentative unfolding that mirrored the essayistic logic of the work itself. This reflects Alison Butler’s notion on the mode of exhibition-as-essay, as she describes the potential of the gallery space as a location for intellectual reflection and rather than being merely a display of research results understanding it as an active debate chamber within an informal public sphere.[2]

Possessiveness and Pensiveness

While this exhibition gesture of wandering and pondering manifested with varying intensities across the different iterations of the work, we began to observe an interesting appropriative behavior emerging among the audiences who encountered the exhibition settings we designed. These behaviors can be well reflected in Laura Mulvey’s concept of the pensive and possessive spectator (see also the discussion in the thesis book Chapter 2.5.). In Beijing, for example, an entire room was dedicated to the work, and visitors actively began to use the furniture pieces we designed for the exhibition, even some of the props we did not initially think would be used by the visitors. As the staff of the Goethe-Institut pointed out in one of our many conversations, the gallery space gradually transformed into a living space. Happenings, such as a visitor heating their dinner in the microwave on display, while others occasionally stretched out on the designed furniture to rest or take a nap, became integral to the exhibition. The installation, in this sense, had shifted from being a space of presentation into one of inhabitation, and thus essentially blurred the line between intellectual experience and domestic rituals. This act of occupation by the visitors, I would argue, generated a complex kind of awareness and intellectual attentiveness, one that is rooted in embodied engagement, as the spectators themselves became active performers within the exhibition environment.

By contrast, the presentation at the Santa Monica Art Center, as part of the ISEA conference, offered a different atmosphere. Embedded within a group exhibition, it lacked the same degree of intimacy, yet a possessive and pensive engagement still emerged. Here, visitors began to contribute handwritten statements on scraps of paper, leaving them within the installation itself. In doing so, they not only built a dialogue with the body of what was presented (and thus, indirectly, with us as authors) but also extended the work’s constellation of fragments with their own. In a sense, they continued to write the essay alongside us. [Fig.]

Such moments as the ones described point to something essential, namely the structural openness of the work. Much like the essayistic gesture itself, the exhibitions were never closed forms, but rather repeated invitations. To borrow once again from Mulvey, the gallery visitor here occupies a position that is at once pensive and possessive: lingering in contemplation, but also appropriating, taking hold of the materials presented, making it their own. In this way, we might also recall Roland Barthes’ notion of the writerly text, in which the audience refrains from being a passive consumer of meaning and turns into an active producer of it.[3] Or, likewise, Jacques Rancière’s idea of the emancipated spectator, who does not simply follow an already-scripted path but creates their own itinerary, digressions, and connections.[4]

As such, every exhibition iteration became less of a fixed endpoint than a generative space of essayistic co-authorship. Visitors did not merely watch or listen; they inhabited, continued to write, rewrote, and sometimes even disrupted the work. Consequently, what emerged was not a determined statement but an ongoing essayistic negotiation between the gallery visitors and the presented materials, one that intentionally remains fragmentary, always provisional, and where meaning was not imposed in an authoritarian manner but continuously made and remade through encounters.

The Archive as Living Entity

Each exhibition of The Smallest of Worlds archive constituted not merely a presentation, but a re-curation of the collected material. Even the core piece, the VR experience itself, was never entirely fixed; rather it was continually adapted, sometimes enriched with newly sent voice memos or additional spatial contributions, at other times reconfigured according to the local context in which it was shown. Likewise, the physical installations embedding the VR experience shifted in their form and articulation with each iteration to produce site-specific variations that continuously reframed the archive anew.

These re-curations were guided by multiple impulses. On the one hand, they allowed us to foreground different aspects of the archive, on the other, they deepened our ongoing engagement with the collected material. For instance, at the Santa Monica Arts Center during the ISEA conference, the exhibition placed particular emphasis on the contributed audio memos, turning the polyphony of voices and their potential interrelations into the central concern. In contrast, the presentation at ETH Zürich, framed by the research orientation of the hosting department, invited us to draw our attention to the processual dimension of the project, to the very cycles of translation and transmedial transformations through which the work materializes. What emerged was a conscious act of staging these moments: from video excerpts to digital spatial fragments, from virtual reconstructions to 3D-printed miniatures, and finally to scenographic configurations that re-inscribed, within the exhibition setting, gestures and situations derived from the contributors’ domestic interiors.

In this sense, each presentation functioned as a temporary constellative arrangement, arrested only in the moment of its public display. The global trajectory of the project, with presentations in cities such as Beijing, Paris, Barcelona, Hamburg, and New York, further demanded contextual sensitivity. Each iteration required a curatorial response to its local environment, whether by including more contributions from the respective area or by engaging on a more conceptual dimension with the cultural, social, or political specificities of the site.

Consequently, as the work assumes the form of essayistic attempts it is essentially unfinished, provisional, and as such in a constant state of becoming. Its logic is less that of a definitive argument than of an open-ended exploration. As Max Bense notes, the essay does not resolve its subject but holds it in suspension, offering a multiplicity of perspectives rather than a single conclusion.[5] This orientation became crucial for us, since the very subject of the work, the fragile significance of private space in times of crisis, resists univocal representation and demands this multiplicity of voices and approaches.

This multiplicity of voices and perspectives on the subject matter is then also the essential gesture towards the audience who experience the presentation of the material. In an essayistic way, they are essentially involved in the process of meaning-making. In each iteration, they are an indispensable part in the constitution of the exhibition’s arguments.

In conclusion, each iteration thus opened a new window into the project and its evolving material collection. Each iteration also challenged us to approach the work with fresh eyes and ears, to re-engage with the material anew. Through this process, the archive of The Smallest of Worlds appeared not as a static repository but as Wolfgang Ernst would say, a living entity — an active agent/catalyst of meaning-making. It became a place charged with unrealized potentials that could only be fully activated through its modes of becoming public, within specific contexts, curatorial gestures, and through the audience’s acts of reception.

Through this process, the archive of The Smallest of Worlds appeared not as a static repository but as Freiling would say, an active agent[6] — living entity of meaning-making. It became a place charged with unrealized potentials that could only be fully activated through its modes of becoming public, within specific contexts, curatorial gestures, and through the audience’s acts of reception.

[1] T. W. Adorno, “The Essay as Form,” trans. Bob Hullot-Kentor and Frederic Will, New German Critique, no. 32 (1984): 170, https://doi.org/10.2307/488160.

[2] Alison Butler, Displacements: Reading Space and Time in Moving Image Installations, chap. 6, “The Essay Installation,” Palgrave Close Readings in Film and Television Series (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), Kindle edition. READ AGAIN

“The essay offers knowledge of the moment, not more. The moment is one of insight, where self and object reciprocally clarify and define each other.” (Graham Good p 8)

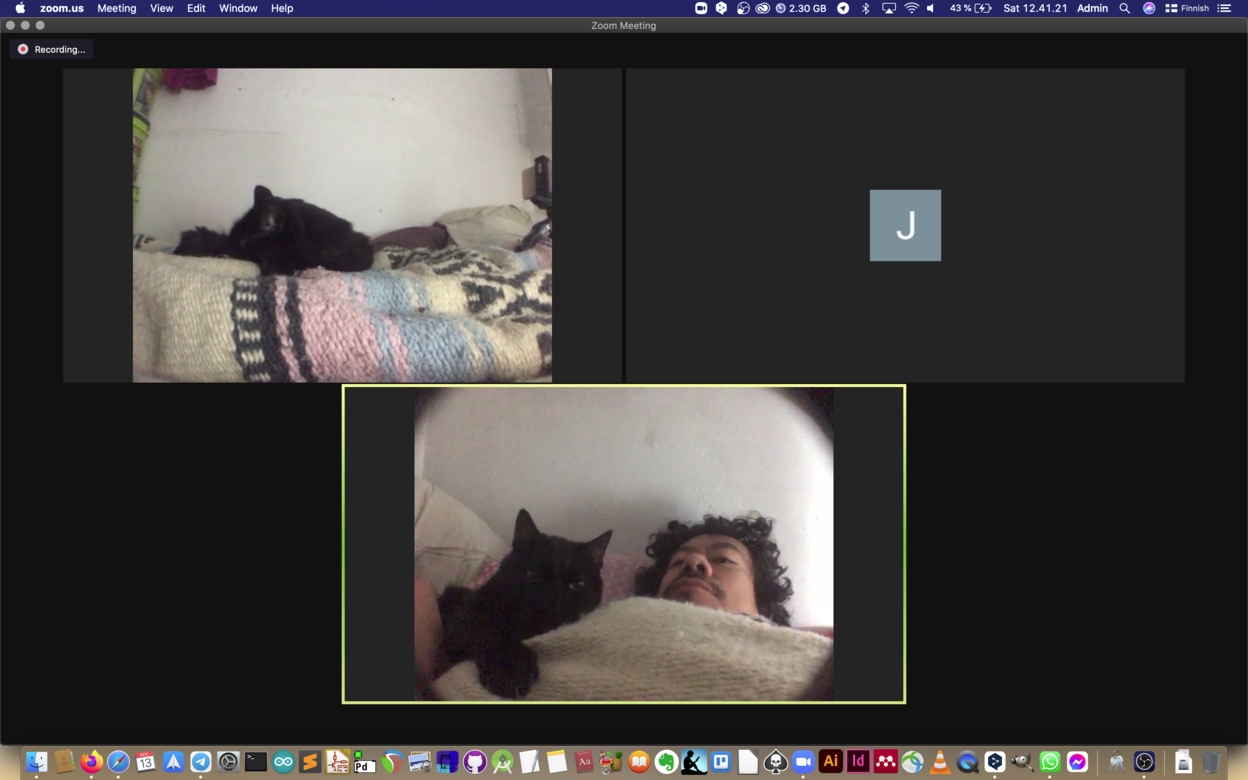

#See You At Home: Rehearsing the Lecture Performance

The online lecture performance #See You At Home on Zoom presented a markedly different mode of engaging with The Smallest of Worlds project and archive, diverging significantly from other occations in which the work was staged and displayed. The performance took place twice, first on November 13, and second one week later on November 21, 2021. Both were hosted by the Goethe-Institut China in Beijing.

Each performance was conceived as a one-hour experience for up to thirty participants, the performance required advance registration through the Goethe-Institut webpage. Two weeks prior to the event, the participants were invited to contribute to The Smallest of Worlds archive, following the same procedure as in the original open call: they were asked to submit a short video of a private portion of their home and a recorded voice memo. These contributions were then used as building blocks to compose a Mozilla Hubs virtual environment, which was one among several other components of the lecture performance.

What made this iteration particularly stand out in regard to other formats and modes in which the work had publicly materialized was the involvement of a group of early participants who had contributed to The Smallest of Worlds archive and with whom we had remained in contact throughout the duration of the project and even beyond. They were invited to co-perform the lecture with us. In the end, several were eager to participate: Rixta from Amsterdam, Alban from Prishtina, Tilemy from Mexico City, Akira from Kyoto/Innsbruck, Anton from Berlin, and Chao from Munich. The lecture performance hence unfolded as a co-creative process rather than a one-directional presentation.

Unlike a conventional lecture format, #See You At Home — The Lecture Performance was designed as an interactive and non-linear experience. Drawing inspiration from the narrative structure of chapters in the VR experience, we created nine Zoom break-out rooms, each hosted by one of the performers. Crucially, the performers were asked to stage their contributions from the very spaces they had originally shared with the project: Alban from his library, Rixta from her houseboat, Tilemy from his apartment bedroom, and so forth. Each Zoom break-out room was staged with at least three cameras views, offering multiple perspectives on both the performer and their living environment. What unfolded within these spaces and during the lecture performance was left to the performers themselves, however, there was one condition, they had to reflect on, or more precisely, to essay the overarching question that guided the project from its inception: what is the meaning of the private space in times of pandemic crisis?

Much to our excitement, each performer tackled the central question in an idiosyncratic yet deeply personal manner. Rixta, herself an artist, embodied this through a performative metamorphosis, gradually transforming herself into a vampire-like figure while mumbling her own reflections on the central theme in the form of an obscure monologue. The theater-maker Alban turned his room into a reading event, straying through his library shelves, pulling pout books, reading fragments aloud, and pausing occasionally to converse with his audience. Chao, both actor and passionate cook, opened his kitchen to the public, inviting participants to share with him the act of preparing a meal. Akira quietly practices Japanese calligraphy within a meticulous created mediative atmosphere; while Anton, a musician, gave an experimental sound performance; and Tilemy, joining from Mexico City at dawn, allowed his audience to accompany him in the probably most quotidian of activities: waking up, performing his morning routine, and sharing the rising sun over the city as it beautifully illuminated his apartment.

We, as initiators of the project, also hosted break-out rooms. At the time being distributed in Vienna, Helsinki, and Barcelona. Bettina and her friend Juan transcribed voice memos from the archive and translated them back and forth between German and Mandarin by using the online tool DeepL. Meanwhile, Joan and I navigated a Google Earth map, zooming in and out of the locations where our performers were based, and juxtaposed this with traversals through the Mozilla Hubs virtual environment, populated with 3D fragments and audio contributions submitted by the lecture audience themselves in the days leading up to the event.

Each Zoom break-out room became a site of encounter, spaces that carried, on the one hand, the unsettling feeling of observation and surveillance, yet on the other, opened the possibility for a fragile but genuine mode of intimate experience.

Structurally, the one-hour performance opened with a brief introduction delivered in Mandarin by Chao. This opening moment was shared by all participants, as every audience member witnessed the same scenario. Moving through his apartment before settling at the kitchen counter, Chao guided the audience not only through the idea and, importantly, the practicalities of the Zoom event, but also wove into this introduction a set of critical reflections. He elaborated on the precariousness of privacy in applications such as Zoom (critically addressing the very platform we were inhabiting), on the risks of data excavation, while raising ethical questions on the sheer possibility of digitally mediated intimacy. In the end he arrived at the ambiguous notion of the private space as a platform, one that, once streamed publicly, could become a stage for self-expression and a site for dialogue.

After this reflective monologue as an entry point, the performance shifted in its mode and form. The Zoom break-out rooms were activated, and the interface suddenly fragmented into a mosaic-like experience. Participants were invited to move freely between rooms, drifting from one domestic performance to another, observing, conversing in the chat, or quietly attending the unfolding of sequences.

Following this second part of the performance, the Zoom call was again reassembled. All participants were moved back into a single shared window, collapsing the dispersed experience into a collective frame once again. At this point, we dropped a link in the chat that granted access to a Mozilla Hubs room. Together, we digitally migrated into this spatial virtual environment, composed of the audience’s own contributions.

In this final phase of the event, the roles subtly inverted, as the audience, along with their fragments, moved into focus. They became the subject of attention, of observation, and of intimate exposure. What began as a guided entry into other people’s domestic spaces ultimately returned to the audience themselves, turning the encounter into a reciprocal exchange and emphasizing the dialectic, often inherent in digital media, namely of seeing and being seen, of sharing and being exposed.

In essence, #See You At Home – The Lecture Performance can be understood as an experiment in the collective rehearsal of ideas and practice of thinking in public. It was a fragmented attempt to grasp and to compose an account of the significance of the private space unsettled in times of crisis, while also critically illuminating the pervasive presence of media under such conditions. In this regard, the central question could perhaps be reframed as: what is the role of private space in moments of pandemic crisis and ubiquitous media exposure? Filtered through many different performances, voices, and minds, the live event became a collective act of essay-making within the public interface of Zoom and Mozilla Hubs, or, as David Carlin perhaps would describe it, a form of collective essaying as a mode of world-making.[1]

[1] David Carlin, “Essaying as Method: Risky Accounts and Composing Collectives,” TEXT 22, no. 1 (2018): 11–12, https://doi.org/10.52086/001c.25108.

“The essay offers knowledge of the moment, not more. The moment is one of insight, where self and object reciprocally clarify and define each other.” (Graham Good p 8)

#See You At Home: An Immersive and Performative Filmic Endeavor

In June 2023 and in April 2024, we were invited to present filmic excerpts from The Smallest of Worlds, first at the Disseny Hub Barcelona as part of the Digital Impact Festival, and at Ars Electronica’s 8K Deep Space, in collaboration with the International Screen Institute in Linz.

For both presentations, The Smallest of Worlds archive was reimagined in the form of an immersive film. This was not merely an audiovisual documentation of the VR piece, as if one were simply recording a walking-through experience, but rather an entirely new iteration of the work. We built an environment from ground up, rec-curated the archive’s domestic fragments, audio memos, and original audiovisual footage. Yet, unlike the VR work, which was composed in smaller, chapter-like units, in the filmic adaptation we sought to experiment with spatial continuity and temporal fluidity, arranging the selected elements into an expansive and open landscape. This patchworked terrain was then digitally traversed, observed, and recorded as a machinima — a film created within the digital environment of the game engine. The movement through the scene was orchestrated by multiple animated virtual cameras, of which some were positioned orthogonally, others tilted 90 degrees downward to capture a top view of the scene. All cameras were synchronized, recording the same scene in real-time, yet from different perspectives.

In the post-production of the machinima, we explored the idea of multi-layered split-screen arrangements by superimposing earlier produced video materials from the project onto the newly recorded footage. We actively employed techniques such as frame-in-frame composition to evoke the impression of an audiovisual mosaic or a mise en abyme effect, where images fold into one another. Conceptually, our aim was for the film to embody the compositional logic of the digital environment, while, importantly, exploring the expressive affordances of its own medium.

The presentation of The Smallest of Worlds as a filmic experience introduced an entirely new spectatorial condition for the work. Whereas in other versions of the piece the viewer is prompted to move actively, turning, navigating, and composing their own path, here the motion is transferred to the medium itself. The animated camera performs the movement, while the spectators remain static, seated, and watching the performance of unfolding images collectively. In both audiovisual presentation setups, the spectatorial experience shifted and transformed a private, individual encounter — as the spectator would experience in the VR piece — into a shared and public act.

In both screenings, we used a dual projection setup, consisting of a wall and a floor projection. This spatial fragmentation of the image into two channels extended the logic of fragmentation and split-screen montage already present within the moving images themselves. This spatial segregation of the visual field within the screening room created a more enveloping and immersive, yet also more complicated and demanding, spectatorial experience. To some extent, we sought to challenge the stasis of the audience by inviting them to oscillate their gaze between the two projections, to continuously adjust their perspective and orientation, and in this process become more conscious of their own activity of looking.

For the screening in Barcelona, we added a performative layer to the filmic presentation. While the film contained an audio track with atmospheric sounds, the plurivocal dimension of the voice memos was reactivated through live bilingual reading by Bettina and Joan. Joan performed a selection of contributed testimonies in Catalan, while Bettina read them in English.

What I found particularly compelling in this setup was that it introduced a different kind of authorial presence, one that was live, situated, and explicitly embodied on stage. The contributed statements were performed almost like a live DJ set, alternating between the two enunciators and unfolding as a dialogue in which both grappled their way through the piles of material. They inhabited the images not only through their voices but also with their entire bodies, through their gestures and actions. In this way, Joan and Bettina were able to react in real time to the audience, adapting to the mood of the moment, shifting tonality and rhythm, and addressing the spectators more directly in order to establish a shared, dialogical relationship.

“The essay offers knowledge of the moment, not more. The moment is one of insight, where self and object reciprocally clarify and define each other.” (Graham Good p 8)

Mozilla Hubs: A Passage for Dialogue — If I could retire I would do it here

Beyond its role as a component of the lecture performance, the Mozilla Hubs room assumed another important function. Between November 6 and 28, 2021 the room was activated, live, and projected as an expansion to the exhibition setup into the Goethe-Institut gallery space in Beijing’s 798 Art District. Visitors were able to traverse the digital environment themselves, using a keyboard and mouse provided in the space, while simultaneously become witnesses to the continuous updates we made to the virtual room throughout the exhibition’s duration.

Most intriguingly, however, the Mozilla Hubs environment became not only a projected window within the gallery space that expanded outwards, but rather an aperture that allowed for a reciprocity, a connecting passage, more like a digital portal. It allowed us, the distant authors, to establish a direct dialogue with visitors on site. In this sense, Mozilla Hubs functioned less as a static display and more as a spatial communication channel, or, metaphorical speaking, a porous interface between the gallery space in Beijing and our dispersed locations. Through it, we were able to converse with gallery visitors, answer questions, performing guided tours, and, basically, inhabit the exhibition from afar, leaving a subtle, but perceivable traces of our authorial presence.

This role was particularly significant given the circumstances that in autumn 2021, the time when the exhibition was produced and opened to the public, we were unable to enter China due to Covid-19 travel restrictions. As a result, the entire project had to be curated and coordinated remotely, with the indispensable and tireless support of the Goethe-Institut team. In this context, the Mozilla Hubs room, then, was not only an online extension of the exhibition to broaden its exposure, but an important and essential link that allowed us to be present from time to time, and, as I wrote in chapter 4.2 of the thesis book, in relation to Chris Marker’s L’Ouvroir it enabled us — like Marker — to extend our essayistic gesture, one that unfolded not only within the media text of the Mozilla Hubs environment, but also through its reflection back into the physical exhibition space.

While the Mozilla Hubs room remained online as a reminiscence of the exhibition, Mozilla declared their intention to discontinue their foray into web-based immersive worlds. As of spring 2024, they stopped providing support and resources for Mozilla Hubs.