Introduction

"Our present scheme of social life in which we drudge behind the scenes most of the time in order to present an "impressive" face for a few moments of company is outworn."

—- R.M. Schindler (in Shelter or Playground)

The Silver Screen Effect / This is where I post from is an essayistic experiment developed as part of the MAK Schindler Scholarship, an artists- and architects-in-residence program at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in Los Angeles, California. Over the course of six months, from April to September 2024, the project explored representations of domesticity in Los Angeles as they are mediated by social media platforms (and channels), and as they intersect with the local real estate industry and emerging proptech platforms. Particular attention was given to the phenomenon of the so-called Content House, understood in its broadest cultural and architectural sense. Content Houses — often also referred to as Collab Houses or TikTok Houses — are predominantly shared domestic environments in which social media influencers and digital creators reside, stage everyday life and domesticity, collaboratively produce content, and advertise products. These houses have been frequently influenced or even managed by companies operating across real estate, talent management, branding, and the entertainment industry.

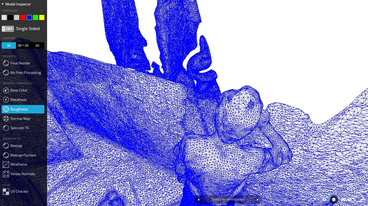

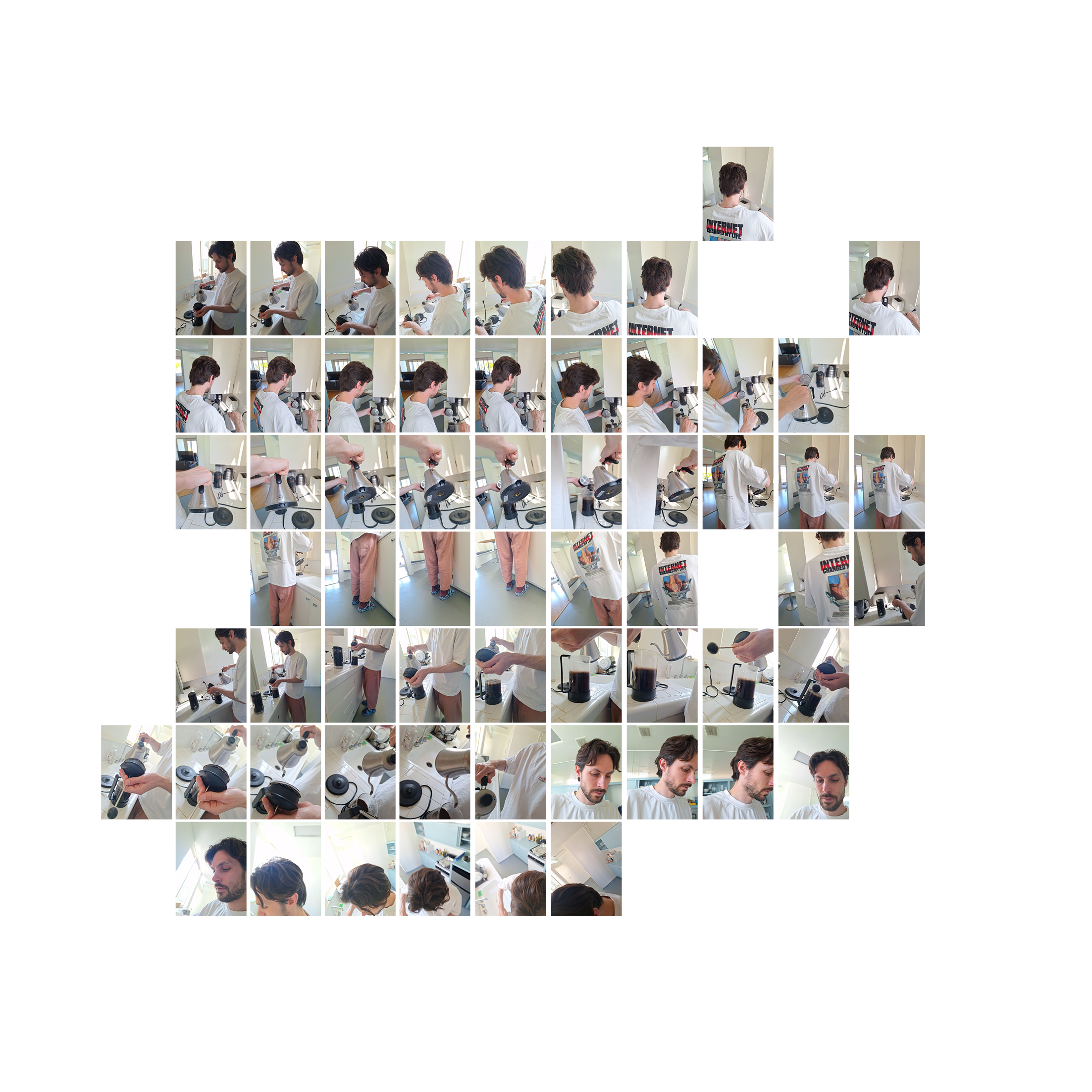

Against this backdrop, the project set out to probe this nexus between social media and the real estate economy through a mode of embodied research, conceived as a self-experiment in life-writing that deliberately blurred the boundaries between personal lived experience and critical inquiry. To this end, we chose to transform the provided apartment, where we lived and pursued our research during the period of the residency, into a kind of Content House itself. This decision initiated an ongoing activity of documenting 3D domestic moments drawn from our daily lives, which were continuously uploaded and published on the 3D asset sharing and monetization platform Sketchfab. These digital captures were accompanied by critical and reflective annotations, situating our lived experiences within a broader investigation into the aesthetics, economies, and spatial politics of social media and the local real estate industry.

Collaborators

Dominic Schwab, Bettina Katja Lange

Format

Multimedia Installation, Online, ... ..

Exhibtions

MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles, USA, 2024.

Tools and Technologies

Setchfab, Polycam, Smartphone 3D scanning ....

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX By XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXexploring

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX myself, XXXXXXXX I X

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX explore XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

all XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX men.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX(Michel de Montaigne)

“ ... it flirts with genres (documentary, pamphlet, fiction, diary … you name them) but never attaches itself to one.” — Jean-Pierre Gorin

- There is no best practice.

- (No one asks a painter «Which is your best brush?» Knowing how to edit in AdobePremiere is not any better for making video essays than using iMovie or drawing on a piece of paper.)

- We use the tools at hand and use them in unplanned ways.

- Videographic practice is an affective, multi-sensory, and bodily experience. We use our bodies, our memories, our intuitions, our flaws.

- What does «essay» literally mean? («essayer»: to try, to try out, to test... [and to fail])

- Restrictions are productive, they are arbitrary but never random (and meant to be overstepped).

- None of us know more than the others in the room, but we all know different things.

- Completeness is not the goal and intactness is not the start – we aim for multiplicity and inexhaustibility.

- Let's not make video essays in order to master anything.

- Seek process, not outcome!

- Let’s not only use audiovisual sources to analyze, question, and problematize the material itself, but let’s also use (misuse? abuse? re-use? appropriate?) them to think about/through/with our lives, cultures, societies at large.

- Let's stop talking about success and start talking about resonance.

- Embrace mistakes, accidents, glitches, and chance!

- Perfection is a disease.

- Be vulnerable and use your privileges accordingly. ” 1

He looks at me.

‘I tell you, I was at rock bottom. Nothin’ left to lose. And there was this force, draggin’ me further into the mess. Took me a minute to get it—this was the devil.’

‘He’s everywhere, man.’

‘Prison. Skid row. Been there.’

“The essayist’s

personality is

offered as a

‘universal particular,’

an example not

of particular

virtue or vice,

but of an ‘actually existing’

individual and unorganized

‘wholeness’ of his experience,"

(Graham Good, 8)

Postings from the Courtyard

Besides the presentation of the essayistic life-writing within the four walls of our apartment, we conceived a second intervention in the residence courtyard, a liminal zone functioning as a connective passage between the front-facing apartments and the gallery situated at the rear of the plot. Particularly, through its in-between status, between the institutional aura of the gallery space and the mundane atmosphere of the apartments, the site became somewhat appealing to us.

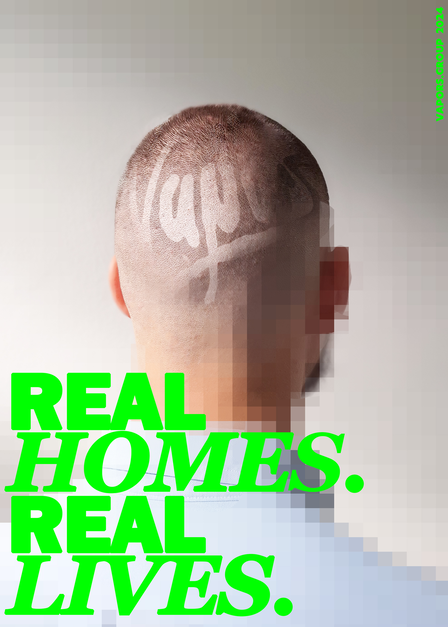

We titled the intervention This Is Where I Post From, a materialization, or rather, a re-staging of one of the 3D vignettes from the essayistic life-writing. As outlined earlier, each vignette seeks to reveal a distinct facet of the intersection between social media cultures and the real estate market in and around the city of Los Angeles. The 3D vignette we chose to re-stage in the courtyard — May 07, 2024 at 05:34 PM, Las Vegas Plaza Hotel Pool — looks at how real estate agents have begun to adopt the rhetoric and performative strategies of influencers, increasingly presenting themselves as online personalities on platforms such as TikTok to market and even to sell properties. Conversely, and by no means less paradoxically, social media content creators, including prominent figures such as Jonathan Carson, have carved out a new niche in entertainment by commenting on real estate listings drawn from platforms like Zillow, Trulia, and Redfin. These proptech platforms, with their vast and ever-growing image repositories, have evolved into ready-made inventories for their sketch comedy-like commentaries.

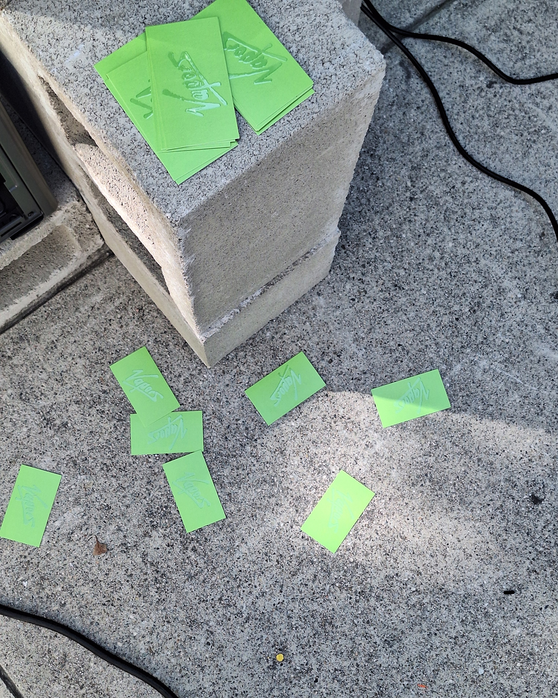

The intervention’s setup occupied an extended portion of the courtyard and comprised of several sculptural and media elements: a sun lounger fitted with a customized green screen; a media tower build from stacked concrete bricks, supporting a monitor that looped a room-tour recording of our favorite listings found on the proptech platform Zillow; a digital billboard displaying a series of designed advertisements, affixed to the trunk of the courtyard’s palm tree; and fictional real-estate business cards scattered throughout the installation. Finally, as its most striking feature, a two-by-two-meter hot-air advertising balloon hovered above the installation setup and the courtyard as a whole, serving as both a literal and ironic nod to the real estate bubble and its absurd speculation dynamics.

In the context of the overall exhibition setup, This is where I post from should not be seen as an autonomous intervention, but an extension of the essay’s digital existence, a fragment, re-staged, re-articulated, and rendered tangible through a material configuration. It could also be understood as one of the essay’s ongoing rehearsals, yet here materialized and situated within the shared, semi-public sphere of the courtyard. These intertextual and intermedial relations between the accumulated digital essay, presented in the domestic space of the apartment, and one of its fragments materialized in form of the courtyard intervention, was further complicated by the fact that, during its exposition, the intervention itself became subject to the same life-writing process: it was captured, spatially documented, and subsequently re-inscribed and published as another essayistic vignette within The Silver Screen Effect diary.

The role of the medium?

This is my first attempt at life-writing, or keeping a diary. I often wonder if capturing fleeting moments in three dimensions can be as intimate as a personal film or a written piece.

I am not sure…

These spatial fragments capture a different kind of intimacy, one that’s hard to put into words. Navigating a three-dimensional document—turning it, rotating it, zooming in and out—gives it a unique accessibility. It’s almost like as you would touch the document. I wonder if this creates a special bond between the viewer and the document?

#container-weave, #container-editor {background-color: }.tool-caption, .simple-text-editor-content, .simple-text-editor-content .x-window-mc, .html-text-editor-content, .html-text-editor-content .x-window-mc {font-family: 'nimbus sans l', sans-serif;color: #000000}

“ Stuff it! Distill it! Stratify and compress it.” 2

“The essay offers knowledge of the moment, not more. The moment is one of insight, where self and object reciprocally clarify and define each other.” (Graham Good p 8)

Group LV: Re-inhabiting the Mackey Apartments

The idea of how to present the work within a public context was guided by a desire to return it to the place where the spatial life-writing process had begun, namely, the domestic space of the Mackey Apartments itself. We chose the living room, with its adjoining balcony, as the most fitting site for its presentation. We placed our working desk, which we used throughout the residency period, in the center of the room to create a spatial separation between the entrance situation and the living space. We arranged on it a computer, a screen, a mouse, and a keyboard, as well as a selection of artifacts that had accumulated throughout the project and carried for us important traces of its development.

Through this spatial and technical setup, visitors could navigate the essay within a specifically designed webpage. Simultaneously, the digital environment was projected across an entire wall of the living room, not only to provide a more immersive spectatorial experience, but also to allow the essay to re-inhabit the apartment again, both metaphorically and phenomenologically speaking. The projection was scaled up to occupy the space as fully as possible, intentionally overlapping with the apartment’s distinctive architectural features, such as the overhead windows and the custom-built shelf-unit that partially cuts through each of the Mackey Apartments.

There was something quietly striking about seeing people move through the 3D vignettes within the very space where most of them had originated, as if the digital and the physical layers of the work, once again, folded back upon one another.

Our choice to exhibit in the apartment, rather than exhibiting in the gallery next door, as did the other artists who shared the residency program with us, was deliberate. It felt more authentic to situate the project within the mesh of its own beginnings. At the same time, this gesture was twofold. On one level, the apartment, a modernist landmark of Los Angeles, is usually not accessible, reserved only for the residents who receive the artistic and architectural scholarship. By opening it, we not only situated the work itself and made it available, but also aimed to design an open house atmosphere, in which visitors could explore, linger, or simply enjoy the apartment in its lived-in state.

On another level, inviting the public into our private domestic sphere became a way to reflect critically on the project’s own trajectory. Having spent so much time examining the phenomenon of the Content House in its various forms and manifestations, and having, perhaps with a touch of irony, identified the residency program and the Mackey Apartments themselves as a kind of Content House situation — albeit artistically and architecturally inflected — it felt only appropriate to let the apartment once again take center stage. In this sense, during the five days of public presentation, the apartment not only turned into a site of exposition but also served as a chamber for dialogue, reflection, and continuation of the project’s ideas.

“The genre can and must be heterogeneous and strange to itself, but its variety and its capaciousness do not mean that it lacks shape.” (Brian Dillon Location 178)”

‘Content is where I expect much of the real money will be made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting.’

(Bill Gates: Content is King, 1996)

Content is ...

Content is Platform

Content is Service

Content is Business

Content is deology

Content is Labor

Content is Exploitation

Content is Tech Language

Content is Queen

Content is Tentacular

Content is Human

Content is Flesh

Content is Product

Content is Subscription

Content is Capitalism

Content is Form

Content is Medium

Content is Contained

Content is Brand

Content is Monopoly

Content is Infrastructure

Content is 🏚️

Content is 🚗

🤳 is Warehouse

🤳 is Space

🤳 is 🏝️

🤳 is 🌐

🤳 is 🕯️

I Digresssssss — VAPORS.GROUP

Another form of materialization, and a distinctly different mode of publication of the work, took shape through the invention of the fictional real estate and media company named, VAPORS.GROUP. This gesture was at once playful, ironic, and critical. It responded to the rather paradoxical strategies and mechanisms deployed by real estate agencies in and around Los Angeles that, with the rise of the Content House, discovered a new and uncharted territory: using their property listings as gateways into social media business and digital talent management. With this move, they not only hoped to boost the market value of their real estate portfolio through relentless hypermediation, but also actively developed a monetization model built around the very phenomenon of the Content House, along with their distinct aesthetic logic within social media culture. This happened through the exploitative labour of influencers, who were often cast and granted with luxury living conditions, yet their stay had to be paid by a steady flow of promotional posts, brand collaborations, and e-commerce adverts, all carefully orchestrated by the hosting agency and often under problematic conditions.

One controversial figure within this system, Amir Ben-Yohanan, a real estate mogul and CEO of Clubhouse Media Group, Inc., went so far as to compare this development to the U.S. Gold Rush of the 1850s, while he, rather unabashedly, cherishes the opportunities born from a yet unregulated market.

It was precisely against this backdrop that the idea of VAPORS.GROUP as a kind of critical alter ego emerged. The name VAPORS itself draws from two intertwined references: Vaporwave and Vaporware. Vaporwave refers to a nostalgic aesthetic rooted in early internet culture. Vaporware, a word borrowed from the tech industry, describes a product that is hyped and long-awaited but endlessly delayed or never released at all.

The idea of VAPORS.GROUP has been made public through multiple channels: a dedicated website (www.vapors.group) linking directly to The Silver Screen Effect essay; a set of business cards; and, perhaps most ironic, a hot-air balloon adorned with the VAPORS.GROUP logo and the company’s web address.

Straying Through Miracle Mile

During the exhibition days, we decided to release the balloon from its controlled environment of the institutionalized setting and to take it into the neighborhood through the performative gesture of walking. These walks through Miracle Mile became yet another mode of making the project public. We strayed through the streets, anchored the balloon in front yards of various properties, and began spontaneous conversations with passersby, who were often curious, amused, or confused about the happening. Occasionally, these encounters would evolve into more intense debates about our study, and many of those felt compelled to later visit our show at the Mackey Apartments.

In this sense, the performative walks extended the publication beyond the physical boundaries of the exhibition setup, transforming it into a lived, dialogical practice.

VAPORS thus existed not only as a fictional company or a digital trace, but as a fleeting, embodied gesture — a way of thinking about visibility, speculation, and participation in the everyday fabric of the city.

“The essay offers knowledge of the moment, not more. The moment is one of insight, where self and object reciprocally clarify and define each other.” (Graham Good p 8)

“ They come in all sizes, shapes and hues — and they will continue to do so.” (Jean-Pierre Gorin: Essays on the essay film p. 270)

‘Content is where I expect much of the real money will be made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting.’

(Bill Gates: Content is King, 1996)

“What does the collector add to the ‘imaginary museum’ in which his thoughts wander?” (Bart Verschaffel)”

“In doing that, not only is the scholar becoming a filmmaker, but, even more crucially, instead of remaining on the position of an outside observer, I insert myself as participant into the very film scene I am analyzing. The scholar’s/film-maker’s body blends with the body of the characters in the film as well as with the body of the film material itself.” (used in Chapter 2.2)” (Johannes Binotto)

ScreenLife: Essaying the Studio

The essayistic life-writing process explored in The Silver Screen Effect also found continuation in the form of a teaching proposal for a seminar at ./studio3 — the Institute of Experimental Architecture, University of Innsbruck. In this sense, the project’s making public took place within an academic context, specifically through a design course with twelve students. This represents a distinctly different mode of publicness, one that operates not through exhibition or presentation, but rather through a form of transmission. Here, the conceptual and methodological seed of the work is passed on to a small group of students who, by engaging with and expanding upon it through their own experiments and reflective engagement, become critical interlocutors in a shared debate about the creative and epistemic value of such a spatial practice in the context of architecture and design education.

The conceptual framework of the seminar was to invite students to engage with a digital life-writing practice within the game engine environment of Unity. Throughout the semester, each student would continuously build and inhabit a personal digital space — a kind of evolving diary, or journal — where moments of life and study were to be documented, reflected upon, and spatially articulated. These environments may not be understood as simply portfolios or showcases of produced work within the semester, but rather multilayered spaces where personal and academic experiences intertwine, and where students could confront and interface with their own processes of thought, of practice, and of self, on different scales and intensities.

The course unfolded in twelve sessions, each session being three hours long, alternating between discussion-based meetings and more intensive two-day workshop units. The discussions in the various sessions revolved around artistic and experimental architectural precedents that explored life-writing, or similar modalities, as creative processes and methods, while the workshops delved into the technical and conceptual possibilities of Unity, with the aim to attune students to the affordances of game engines and to equip them with the necessary tools for developing their own essayistic life-writing practice.

As emphasized in the seminar description, the course was closely linked to each student’s main architectural design project, which they were developing simultaneously within one of the faculty’s many design studios. I found this connection quite essential, since it offered both a foundation and an impulse for beginning their life-writing process. Drawing on my own experience as a past architecture student, so much of architectural work, the long hours of thinking, sketching, modeling, doubting, and rethinking, mostly remains invisible in the final presentation of a project. These moments and processes, however, are where the actual intellectual and emotional labor of design unfolds. The seminar thus actively encouraged students to become aware, capture, and preserve these often ephemeral layers of their work — the fleeting thoughts, failed model attempts, and idiosyncratic late-night notes — by recording and storing them within their digital life-writing environments.

The Critical Self as Meta-Gesture

In principle, the course adopted a process similar to the one I had developed within my own essayistic practice. Its structure was divided into three main activities: a collecting phase, a curational phase — both were conceived as parallel activities throughout the entire duration of the semester — and finally, a publication phase. The latter culminated in a performative walk, each student navigated through their own life-writing environment with a live vocal commentary. This performance was presented within a public exhibition setup at the University of Innsbruck.

Importantly, upon beginning with their essayistic life-writing process, each of the students was confronted with a set of guiding questions. First, and most fundamental, each was asked to develop a personal strategy for documenting both their academic activities and their life outside the university. How might they document these experiences across different media, such as textual, audiovisual, and spatial? Second, they had to consider how the evolving collection of materials could be staged: would it be an affective and intuitive, or rather a carefully planned process; chaotic or ordered; spontaneous or systematized — or anything between? And what would their temporal framework be? Would the curational effort happen daily, weekly, or fluctuate in intensity over time?

A third and most challenging question concerned the ways in which students could essayistically inscribe themselves into their spatial composition, to position themselves as a kind of extratextual enunciator through a form of second-order inscription. Second-order inscription means here not simply a form of self-expression, but a meta-reflection of how the self is constructed and appears within the fabric of the work. In a way, it has to be seen as a gesture that turns inwards, reflecting on its own makings as a conscious echo, and simultaneously outwards, as a voice that exists outside of the work to form a direct address and establish a dialogue with its audience. In this sense, what strategies could they develop to establish such a layered meta-reflection that holds all fragments together and draws the visitor into an essayistic dialogue?

This last question, also, carried intentionally a little provocative note. In conventional architectural and design education, unlike many art-based pedagogies, the inscription of the self, the subjective stance, and the personal affective nature of practice are often pushed aside in favor of a more objective and logic-driven presentation of results. In this sense, students were confronted with the task of foregrounding their own subjective voice, their idiosyncratic thoughts, and sensitivities rather than concealing them within the process.

In response to this set of questions, the students developed a range of approaches and, consequently, a wide variety of essayistic life-writing environments emerged. What quickly became apparent was the desire of all students to work across media, to combine text, image, audio, video, and 3D objects. They tended much more to work with the multiplicity of media than to narrow themselves down or even confine themselves to a more uniform mode of articulation. Notably, as well, many students placed a strong emphasis on worldbuilding, constructing atmospheric and thematic environments for their documentary materials to be nested in. This ranged from vividly composed, forest-like worlds, to labyrinthine fantasy environments reminiscent of dungeon mazes, to minimal, abstract spaces — and of course, everything in between. Each of these atmospheres was in some way tied to each student’s individual main studio project and evolved in parallel with their documentary activities in the seminar. As the semester progressed and the students became increasingly attuned and immersed in their design work, these atmospheres grew denser, more meticulously constructed, and more intricately entangled with their spatial life-writing process

Perhaps the most complex task, to inscribe themselves as a layered meta-activity, and find ways of addressing the yet-to-be-imagined visitor of their environment and building a dialogue with them, felt much more difficult for the students. While many used in the end an interesting symbolic gesture, namely the implementation of a digital recreation of themselves — a kind of explicit, yet mute inscription — a third-person avatar through which a visitor could navigate the environment. However, more intimate and reflective gestures of self-inscription, capable of forming a genuine dialogue, often took shape through other, more traditional modes. Some chose to embed textual diary fragments dispersed across the digital landscape, or to weave in audio memos that would activate as reflective sonic layers when approached by the visitor. Others engaged with the challenge of self-inscription more on a visual dimension, by incorporating traces of their everyday lives through evocative images, video clips, or 3D scans of objects and domestic settings.

However, it became evident that this form of second-order inscription — the meta-dimension of revealing interiority — did not come as easily as other activities in the spatial life-writing process. It required a particular sensitivity and openness to expose vulnerability, a quality that often stands in sharp contrast with the conventional codes of communication within design representation. Yet, among all the student works, it became clear that it is exactly within these fragile layers of self-reflection and self-reflexivity that the collected materials, as part of the life-writing process, are held together and gain their most profound value, namely, the moment where the particular and the situated subjective begin to resonate with a wider public, becoming meaningful as something universal.

This, I believe, marks one of the most interesting aspects to be further explored and discussed in future iterations of the seminars.

“Our present scheme of social life in which we drudge behind the scenes most of the time in order to present an "impressive" face for a few moments of company is outworn.”

—- R.M. Schindler (in Shelter or Playground)

“The genre can and must be heterogeneous and strange to itself, but its variety and its capaciousness do not mean that it lacks shape.” 3

“The

‘I’

of

the

essay film

always

clearly

and

strongly

implicates

a ‘

you’.” 4

“How I loved to stuff myself with the unripe, the unready, the rough and ragged greens of undigested thought … Bricoleur is what I am. Collector of scraps: sappy, juicy, unraveling, precipitous. Fragments I yearn together …” Bird: A Memoir' by Susan Mitchell, Erotikon

3D Documenting as Spatial Life-Writing

Among the works that influenced me the most during the development of The Silver Screen Effect / This is where I post from were Jonas Mekas’s 365 Day Project, Will DiGravio’s Rio Bravo, and also John Smith’s Hotel Diaries. All three works have a durational component inscribed. Mekas’s and DiGravio’s works even adhere to a strict routine of producing and publishing a clip every single day.

While these works were realized in audiovisual formats, I sought to extend the principle of daily production into a spatial practice, employing 3D scanning and photogrammetry as my medium, using a smartphone and tablet equipped with an application called Polycam throughout the duration of the project.

Maintaining such a persistent rhythm of documentation proved at the beginning undeniably difficult. It required a long period of adjustment before the process felt remotely effortless and became an intuitive gesture. Nevertheless, it was precisely this heightened self-involvement in the act of documentation that became most interesting for me. The method not only built a bridge to precedents in diaristic and essayistic practices but also positioned me in proximity to the very subjects of my research, namely content creators operating within popular formats such as Living Alone Vlogs or influencers residing in TikTok Houses. By embracing their routines, I temporarily embodied the conditions of the practices I was investigating, blurring the line between my research investments and lived experience.

The aim of the spatial life-writing method was to construct a diverse mosaic of domestic life, which gradually expanded outward into everyday activities beyond our immediate living space, such as research trips, site visits across the Los Angeles area, and even excursions further afield. Each act of 3D documentation demanded a momentary suspension of movement. When either I, Dominic, or Bettina slowly circled the scene, attempting to 3D scan it, the subject had to remain still for about two minutes. Factors such as overall lighting, steadiness of movement by the documenter, and camera quality further determined whether a convincing 3D artifact could be generated.

This technical and performative demand formed one of the central barriers of the process. Unlike the quick immediacy of a smartphone snapshot, each 3D scan required time, coordination, and the willingness of all to participate. Yet, what at first felt almost like a violent intrusion into the fluency of everyday life eventually became part of a shared rhythm that transformed the act of documenting into a small, collective, and recurring performance. Precisely through this collective effort and attunement within the group, the act of 3D capturing gradually turned into something quite immediate and intimate, at times even sparking a reflexive gesture in itself.

Over six months of residency and research, we produced more than one hundred 3D documents. In the end, for various reasons, 67 were finalized and published on the 3D infrastructure of Sketchfab, forming a fragmented record of our lived experiences, research practice, and daily routines.

Embodying the Research: Life-Writing as (Re)collection of the Self

The spatial life-writing process became a way of being in resonance with the practices of social media influencers and content creators whose vlogs and media channels I was following and studying. It allowed me to gather an implicit kind of knowledge, namely to understand, at least to some extent, what it takes to inhabit the practices of these creators from within, and also what it means to adapt to the labor logics characteristic of a so-called Content House. This constituted access to a form of knowledge I could not have penetrated otherwise. Becoming accustomed to their rituals offered me a different perspective on the subject matter, one that emerged through proximity and re-enactment rather than purely observation.

While it must be pointed out that I did not work with audiovisual means, but rather through 3D scanning techniques, yet this mode of engagement nevertheless enabled me to develop a certain sensitivity toward the gestures and aesthetics of this practice. It also prompted me to reconsider — even to confront myself with — the preconceptions I carried with me when I first approached the topic.

But, to be more concrete, what kinds of findings did this process actually yield in relation to my research? What insights did this practice open up? Retrospectively, I can say that it sharpened my awareness and generated forms of discreet, practice-based knowledge, insights that could only be gained through the investment of doing. For instance:

I became more sensitive about the labor involved in producing such content.

I felt how content production can rhythmicize and structure daily life, creating routines around filming and editing.

I recognized how I began to understand my apartment we inhabited at the time of this research differently, namely through the lens of its affordances for content production. This included adapting the layout, becoming more aware of light conditions, attuning to atmospheres that worked better in 3D captures, and even considering what to wear in relation to the apartment’s colors.

I simultaneously developed technical fluency with the 3D capturing technologies and the application I was using.

I became more sensitive to how domestic rituals are produced, framed, choreographed, and staged within these social media formats.

I became more explicitly aware of the tension, or better the negotiation between authenticity and performance that have been adopted by these content creators.

“[…] the essay always speaks of something that has already been given form, or at least something that has already been there at some time in the past; hence it is part of the nature of the essay that it does not create new things from an empty nothingness but only orders those which were once alive. And because it orders them anew and does not form something new out of formlessness, it is bound to them and must always speak ‘the truth’ about them, must find expression for their essential nature.5

Prelude

The work, The Silver Screen Effect is perhaps my most explicitly personal one to date, as I — in the form of the enunciator — appear regularly within it. It is also the work in which my lived experience of being in Los Angeles, inhabiting the city, residing at the Mackey Apartments designed by Rudolph M. Schindler, most vividly intertwines with my research activities themselves. This situation also led me to a mode of experimentation with what I began to call a spatial life-writing process, a form of daily capturing and documenting my lived experience in a diaristic manner. The term life-writing is well established within literature studies. It refers to a broad constellation of free, often eclectic, forms of life narrative: writings concerned with lives, fragments of lives, or the very material from which life stories can be traced and assembled. Life-writing stretches across a wide variety of expressions, such as biographies, autobiographies, bio-fictions, diaries, memoirs, journals, letters, weblogs, and social media entries, among many others. Cultural Studies scholar and specialist in life-writing Margaretta Jolly extends the practice even beyond its literary scope. For her, life-writing also takes place in non-literary media, such as the visual arts, photography, film, and other cultural artifacts.

In my engagement with the essayistic mode, I found myself increasingly drawn to forms of life-writing with diaristic inflections. Life-writing, such as the diaristic as one of its modes, places the “I” at the center of the text and therefore remains closely aligned with the essayistic mode. As Laura Rascaroli notes, the diary can be understood as a subcategory of the essayistic, where the subjective and the reflective converge. Indeed, an essay may be composed of life-writing fragments such as diary entries, and conversely, life-writing practices can themselves assume the form of essayistic accounts and gestures.

In shaping my essayistic life-writing approach, I was strongly influenced by Jonas Mekas’s practice of diary filmmaking. For me, his practice demonstrates so evocative how the diary form can open a space between self-documentation — and as such the autobiographic — and wider cultural, political, and critical reflection.

The origins of my exploration with forms of life-writing and the diaristic go back to a workshop I co-led at the Vienna Architecture Summer School in 2022, together with Dominic Schwab, Cenk Güzelis, and Stefan Maier. In this workshop, we experimented with what it might mean to produce a collective diary through spatial media. With our participants, Dila Kirmizitoprak, Yannick Datzer, Lucia Herber, we tested a range of spatial documentation practices like 3D scanning, photogrammetry, and volumetric video recordings, among others. Over the course of a week, this experiment evolved into an intimate process of self-documentation, where participants captured themselves, their routines, and immediate everyday surroundings. The resulting work, then, was a collective diary composed within a digital spatial environment and presented through VR technology as an immersive experience.

One year later, and still encouraged by the results of this workshop, I reanimated this method and practiced it the context of a university excursion. In 2023, I organized a study trip New York with my colleague Cenk Güzelis at ./studio3 – Institute for Experimental Architecture. Throughout the entire trip, I conducted multiple daily 3D scans of the group and our activities, with the aim of constructing a spatial diary of the excursion. I did so, and this accumulated record was later shared with all students who participated in the trip. Interestingly, two of the students, Julia Muschler and Altagracia Spannring, further used this material and developed an interactive video game using the 3D scans as a basis to construct a walkable memory space of the time we shared together in New York. It is only safe to say that these were the stepping stones that led to the conception of The Silver Screen Effect.

Sourcing, Scraping, Clipping: Gathering Associative Material

Alongside the spatial life-writing process, with its embodied insights, another, parallel mode of material gathering and knowledge pursue unfolded. Whereas the former was situated in daily lived practice, this second approach aimed to investigate the broad phenomenon of Content House from a more distanced, detached observatory angle. Here, the focus was placed more on tracing genealogies, resonances, and historical continuities of the Content Houses through various media and formats.

This process took shape primarily through the collecting of associative materials, most of them sourced from the internet. The techniques were: screenshotting and screencasting, video clipping, online texts sourcing and secondary literature review, as well as scraping of online forums. Gradually, these fragments were synthesized into a multimedia research journal using the Research Catalogue, which served as a provisional site to form associative thoughts, establish temporal associations, and record observations. In this sense, keeping and maintaining this journal was itself a meta-reflective activity, a space where I could reflect once again my knowledge-generating procedures.

The material collected was intentionally much more heterogeneous in its medial form than that we gathered in The Smallest of Worlds. It spanned the entire spectrum from the seemingly utterly trivial to thoroughly rigorous. Social media posts claimed their space next to academic literature; real estate tours besides music industry ephemera; archival documents alongside memes and GIFs. Photographs, videos, and sound recordings from fieldwork coexisted with screenshots and screencasts gathered during online meanderings. This assemblage reflected not only the multiplicity of the subject under investigation but also the impossibility of isolating the Content House phenomenon from the wider cultural, economic, and technological ecologies from which it sprang, and through which it continues to evolve.

In this sense, the gathered material did not aspire to form a linear account or even narrative closure, but rather to generate constellations of meaning and associations in which a tentative account — or fragile image — of what a Content House might be, where it has come from, where it could drift next, could appear and remain fertile ground for further debate.

“In the glass life, everything can be used. It is all material.” 6

“[…] I increasingly have this urge to appear in my videos and thus in the films that I am working with. To be physically present in them, as a vulnerable body. And one of the explanations for me is that I’ve always already had that desire, also when quoting something — to be in conversation, to be in the same room with the author I am quoting.” (Johannes Binotto)

“The kind of thinking that grounds an essay is picking up, preserving, collecting, waiting, until a figura, a constellation of images or words emerges, the prelude of a thought.” 7