As with the music by Rolf Wallin and Helmuth Lachenmann, this doesn’t offer the singer much musical freedom - it is all there, very exactly notated, in the score: the different voice qualities, and sometimes even the way I move my body. The sense of freedom comes only after hours of practice, and then it is still the composer’s intentions I am delivering. Now, I know that both Bauckholt and Wallin want the performer to have artistic freedom and take ownership of the music, so I’m not talking about being controlled by a ”demonic master ”composer (the ”tiger cage” that Fia Adler Sandblad talked about in our dialogue in chapter 4, is comfortable and spacious). However, there is a huge difference in the way I make music. Monteverdi and his contemporaries require us to improvise and play with the music - to go outside the written score, while Bauckholt, Wallin and Lachenmann need us to stay within their frame. I don’t play with this, the same way I would ‘play’ with Monteverdi, where ornaments are added and rhythms and timing change after my whims at that very moment.

(A little note though: Carola Bauckholt often gives the singer some freedom to pick her own tessitura - the pitches are in certain places approximate, and Wallin does the same in some parts of ”…though what made it”.)

What did I bring to L’Orfeo:

One example of how I directly linked this to my L’Orfeo-process,and vice versa was Messagiera. Monteverdi writes un uneven rhythm for her, as to illustrate her distress. Striggio gives her strong words ”Ahi caso acerbo, ahi fat'empio e crudele. Ahi stelle ingiuriose, ahi ciel avaro.”FN She is well aware that her words will kill Orfeo. She doesn’t want to say them but she has to. In Rolf Wallin’s ”…though what made it has gone”, I found a key that helped me sculpt her and her voice within me. ”…though what made it has gone” starts with the phrase: ”What I say now is not said by me”FN. Wallin chops up the words and makes them impossible to understand; sometimes the ”sssss”s goes outwards and sometimes inwards as if I’m trying to catch my breath, or as if I am crying. Bringing the affetti of Messagiera into Wallin’s music as an experiment, turned out to give me a personal intention, giving both consonants and vowels a meaning beyond the pure sounds. When I returned to Monteverdi, Messagieras part, inspired by Rolf Wallin, her crying and desperation found an intensity I hadn’t heard before.

Could the 17th-century actor-singers have used what we today call Extended Vocal Techniques? Probably not. But, when the singer’s treatment of the text as ”singing,” it’s unavoidable to sometimes move away from the generic, classical singer norm - thus, in this case, Extended?FN

In recent artistic research projects Alex Nowitz, ”Monsters I Love”, and the already mentioned Øystein Elle, ”Capto Musicæ” both investigate the ”extended voice”. In many ways our work intertwines; cross-over singers/musicians with a desire to use our whole instrument, and musical and singing being, exploring what the human voice is actually capable of. Nowitz describes his starting point: ”Over the course of twenty-five years experiencing a variety of diverse vocal practices from different æsthetic fields, such as opera, improvisation, new music compositions, Jazz and Rock-related experiments, etc., I have come to learn that there are ways to go beyond boundaries hitherto considered impossible. The question then was and is how might we transcend limits and how far might we actually go?”

My wish in these projects was not to see how far I can stretch my voice, but to investigate what is already there. I would only need to extend it if when the narrative and texts asked for it. Though needless to say, I agree with Nowitz when he claims that ”the classical approach to vocal arts in Western culture, the concept of the one-register voice, to put it very bluntly, squeezes the actual potential of the voice in a tiny little box providing only a small palette for the composer to draw on.”FN

Classical singing is, in my opinion, already an extended and extreme form of using the voice. We manipulate the muscles and vocal cords into making the most amazing sounds, but, I dare say, it is extreme.

Personally, I find that problematic, it implies that the classical ”Bel Canto” is the norm and that which differs from it is ”Extended”. Elle argues in the same way: ”Within Western art music the techniques based in Bel Canto are still the most common vocal aesthetics. And although one could argue that the highly stylized voice as it occurs in the operatic tradition is a vocal extension, the term Extended Vocal Techniques is understood as a designation of the techniques that escapes the tradition of Bel Canto.”

From my personal standpoint, some of what we call Extended Vocal Techniques are closer to the basic functions of the voice: crying, sighing, laughing.FN

”Before language was developed, the voice's primary function served for uttering emotional sounds’ such as weeping, laughter and warning cries. Despite the secondary conditioning by voice training and the culturally generated differences inherent in all speech and song, the connection to this primitive stratum still exists. The voice may directly express a human being's psychological state and express a nuanced emotional life. Joy, sorrow, enthusiasm and despair may be heard within a single sound…” Susanna Eken FN

The mini-opera ”Beyoncé and Beyond” by Rebecka Ahvenniemi, was commissioned by Bergen Nasjonale Opera as part of the Future Opera-project - three new operas in one evening.

The following conversation is a fantasy collage made with parts of an interview with Rebecka Ahvenniemi by Ida Habbestad, after the premiere of ”Beyoncé and Beyond”. The method of cutting and pasting the interview I have re-interpreted with the same method I used in L’Orfeo (as I am discussing in chapter 8 - The mise en scene). I have added my own thoughts to this conversation as if I had been there myself.

The original interview is found here (in Norwegian, the translation into English is made by me.)

Chapter 6

Leaving it

- and finding the Otherness of L’Orfeo

A very important chapter on how I used contemporary music, pop, and cross-over in L’Orfeo.

There is new research showing that the brain works in different ways in different types of musiciansX. Neurons activates different parts of the brain if you are a musician who improvises a lot (jazz and some baroque musicians) or if you mostly play from a score (the normal classical performer).FN There is even research showing there might be actual differences in personality between performers of different genres. Extroverted Folk musicians, risk-taking jazz musicians, introverted classical musicians…FN

Then, there are us... We, who feel most whole when we are in the Doubleness, and the in-between, or when we can go from one to the other.

Touching the Otherness of our selves. Making contact!

(Is this how Anna Renzi’s brain worked? Not wanting to choose, needing to be all? Neurons jumping back and forth in her brain?)

Rebecka Ahvenniemi: I have asked myself how I, as a composer, and as a woman, can approach the opera format today, when almost the entire reference basis is created by men.

It is not irrelevant who made the libretto or music for an opera. In itself, the opera form reflects society, the political and social structures at any given time - including gender ideals. Anyone who has access to this also has access to define.

Elisabeth: I think that is part of my personal problem with Opera as genre. Even if I know we are, as you said, part of a culture and history, I have to respond to it from where I stand today, and at the same time understand of the time it was created. But all these young, beautiful women who sings and then dies (as Euridice and, in a way Proserpina) or being banished (Messagiera FN)… The same kind women who get killed in every crime-noir… So, there are some things that haven’t changed.

Ida Habbestad: Also, in terms of content, opera has often themed political and social structures. Your input was, among other things, to choose Beyoncé as a reference?

R.A: Beyoncé symbolizes the tension between being a woman in a position of power, and at the same time, being just that: a woman. Beyoncé is rich and famous. She is a songwriter, music producer, pop singer, and feminist. At the same time, she expresses herself through extremely sexualized female roles in her music, which can be seen as problematic from a feminist perspective.

Bild

R.A In the beginning of this opera (”Beyoncé and beyond”), the star is born from Orpheus' dream. However, the focus is on her, and she arises as a result of Orpheus's imagination.

Here, I recreated a musical aesthetic based on Monteverdi's operatic style (as well as Purcell, Mozart e.a). I have also experimented with the tension between the vocal technique in the Renaissance and early Baroque, and improvisational singing in R & B style, which is not necessarily very far away.

Elisabeth varies between chest sound and head sound, depending on the style…

E…and those shifts were sometimes very fast. You could make me go from ”Beyoncé” to Monteverdi in the middle of a melismatic ”wailing.” John Potter (as I have returned to many times) claims that modern pop singers might be closer to the late renaissance singing ideal than modern classical singers. In this opera, I got to test that. And as with my earlier experiments with Susanna Wallumrød (whom I will come back to in a bit), I decided that I like this connection, and feel vocally connected to it.

And of course your Orpheus link is extremely suitable for me! (laughs)

I.H: How have you thought about the dissemination of text - also musical - in your work?

R.A: I have written large parts of the libretto performed vocally in a constructed Italian-Latin-like language, which sounds like an "opera language". There is also an English text.

E: At first, I did not take the text seriously but played more with it. Because it is a constructed language I could do this - some of the respect we can have for a language we don’t fully master disappeared. Later, the seriousness crept in, so to speak, without me noticing even it.

R.A: One purpose was to make the text genre we actually encounter in rap, R&B, and pop songs more visible. The lyrics become more striking when they are detached from their original context and format.

E: It also made me sing the quite explicit lyrics with a distance that made them appear even stronger. It is an intriguing way of writing a libretto. You used so many parameters: sounds, semantics, nonsense…

Going back to Monteverdi and L’Orfeo, I can totally see Proserpina in this story. She is a QUEEN, but our modern gaze tends to view her sexual playfulness as submissive and victimized. Definitely Euridice! She is characterized as an innocent woman - but is also a tree nymph, who’s name means Wisdom.

R.A: Yes, it's not just a sad story of the oppression of women. When the main character is born, she doesn't have a name, she is just beautiful (like Euridice). After a little while we see a distinctly strong personality; she is diva, ambitious, and pompous.

It was the ambiguity and duality in Rebecka’s opera that aroused my desire to explore Proserpina and Euridice in a new way. They are also sexualized women, who can easily be interpreted as the Madonna and the Whore in our eyes. I felt really ashamed when I, a woman and feminist in the 21st-century, realized I had formed them as the stereotyped weak women they appear on the paper. When I could see them as whole persons, with stories and wills of their own, the entire narrative changed. I used the energy, and also parts of Rebecka’s music, when I worked on ”The Tree with a name” with Wolfgang Lehmann (see chapter 7). Beyoncé was a fabulous and powerful igniter for this.

Questions asked:

Am I two (or three, or fifty) different singers/musicians/roles depending on what genre or style I'm performing? What divides them? What ties them together? What factors determine how the voice will work, or not? Can I use the interpretation of opera characters to better understand these roles?

What can I use from my knowledge of early music in my practice as a performer of contemporary music, and vice versa?

How different is my voice really, when I perform different styles and roles?

What happens when I connect them instead of separate them?

Method: With an auto-ethnographical mind, the sessions, workshops and projects were carefully investigated and observed: How did I behave in the surroundings I put myself? What happened to my voice? How important were the people who were there with me?

In the centre, as always, is L’Orfeo and how the story of him best can be told.

The constant dialogue between L’Orfeo and my different selves.

Dialogue, or touching? Meeting a stranger? ”All touching entails an infinite alterity, so that touching the other is touching all others, including the ”self”, and touching the ”self” entails touching the stranger within.” Barad. FN

Originally I wasn’t going to bring New Music into this project. I would perform L’Orfeo all by myself, and by that bringing Magnus Tessing Schneider’s theories on role doubling in early operas, to an extreme. Still, I had to understand why as a singer I needed to do this in the first place. My constant switches between strictness and freedom, melodic singing and EVT, new score based work, strictly notated music and the early music yearning for improvisation and creativity.

Øystein Elle and his artistic research project ”Capto Musicæ” is one project I can link to mine. He also merges early music with different contemporary expressions and theatre, but he seem to be able to collate the pieces: ”…in an artistic context where boundaries between genres and disciplines are becoming increasingly blurred, this mixture of expressions emerges as its own distinct creative field.”

For me, the boundaries aren’t blurred. Instead, over the years they have become increasingly firm and stable, making the jumps between them harder and harder, to the extent that I see myself as a completely different performer from one day to the other - multiplying my own roles.

In these projects I aimed to create that ”mixture of expressions” and let them ”emerge as its own distinct creative field”.

If Monteverdi is ”easy” to learn, this is not.

First: The score. I look at it, and I have to understand it… At first blurry and unclear, but gradually: note by note, bar by bar, I knead the music into my vocal cords and muscles. Over and over again. And Again. I have on occasion even used a ruler to understand where the pulse is, and how the bars are constructed. The music can be like a big puzzle where I carefully put piece by piece together, and slowly an image appears and I begin to see the patterns. Harmonies and melodies emerge from the blurred and unclear.

It is struggle, and a reluctance to go into the unknown, of uncomfortable intervals, of different understanding of tempi, of extreme highs and lows. Extreme use of the voice - leaving the classical technique and shifting into Extended Vocal Techniques (see later in this chapter), bending the voice and forcing the vocal cords into unknown sounds.

Sometimes I feel that my own will is controlled by someone else, that I, myself, ambeing reconstructed; or as Ellen Ugelvik said about the process of learning ”Serynade” by Helmut Lachenmann: ”It sometimes happened that when playing, you have to re-learn the instrument. I mean that I had to destroy something inside myself, the way I've played and listened to myself in the past, and build something bigger and more nuanced. It hurts!”FN

And then, the concentration in the meeting between the other musician/s. Collecting energy and making music from the complex scores. Slowly we understand the language of the composer together.

Neither of these two works is a traditional ”soprano accompanied by pianist” - the voice and the piano blend together and become a single instrument. The process with Kenneth Karlsson was thus characterized by collaboration and uncompromising cooperation. Every measure is chiseled together. This would never be the case with music from the 17th-century, where everyone is important, yes, but the instruments the instruments revolve around both voice and lyrics

Secular Psalms was commissioned by Vollen United as a part of the marking of Barbara Strozzi’s 400 years anniversary. Buene’s task was to choose a piece by Barbara Strozzi and place that in his own musical context and language. We wanted him, and us, to play with boundaries, breaking them, and create something new.FN

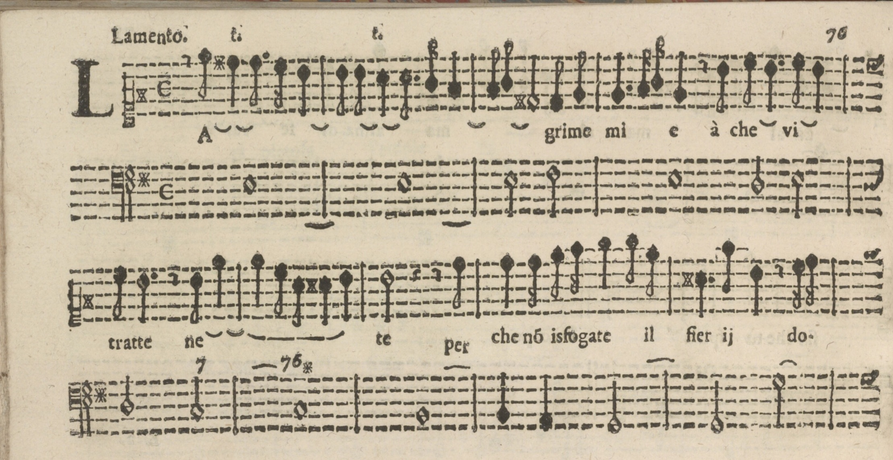

Eivind Buene chose the lament ”Lagrime mie” by Barbara Strozzi. I sang this aria the first time as a singing student in my early twenties. It is, by many singers, one of Barbara Strozzi’s most loved laments.FN

Buene had used a modern print of score (this is a score that can be found on the free music database imslp), where the editor had added a ”ficta”, a ”natural”, that doesn’t occur in the facsimile, and with that, he added an extra chromatic movement. I can’t say for sure that this was wrong, but neither have I sung it like that before, nor heard anyone else doing it.

Eivind couldn’t know this - he only saw the modern print where the publisher made some choices for us (see chapter 3). It looks correct (and maybe it is! We don’t know!!), but it felt wrong for me. Despite the for me, alternative melody line, my body remembered the song well and I should have been able to sing it without any difficulties. The setting however is unfamiliar and I feel lost: On the one hand, I have a lutist (Fredrik Bock) whom I’ve sung with for many years (and have even recorded this particular Strozzi-song - I will come back to that). On the other side, a pianist (Kenneth Karlsson) whom I’ve also worked with for years, but then on a repertoire consisting of mainly 20th- and 21st-century music. The cellist, Inga Grytås Byrkjeland, is a musician who, like me, jumps between different genres

Buene wanted me to use my ”baroque singing style”FN, but the piano line is romantic, and the overall sound in the piece is too…” timeless” for me to feel comfortable doing that. And, again, what is a baroque singing style? It is anything but an imagination, a modern fabrication. In the book ”A history of Singing”, John Potter and Neil Sorrel discuss how the ”baroque sound” came to be what it is today. Their main perspective is British vocal music sound, and how it emerged from the cathedral choirs with their long and unbroken traditions, ”This is not a style rooted in any consideration of historical performance practice but is a living traditions based on a certain sort of musical discipline; for most choristers it is the only ”proper” way to sing”.FN This makes it easier to understand why we consider vibrato-less voices more ”HIP” than a fuller voice. But is this to say, it was an ideal for a female soprano who doesn’t sing in a choir? I don’t believe so. Anna Renzi, as a female actor-singer, should also be quite far from an English Cathedral choir with only boys and men.

I discussed in chapter three, how modern pop and jazz affected this research project. Here I am taking it a bit further.

The most common sound of a baroque singer today is a leaner and cleaner version of the modern ”19th-century bel canto” singer who sings with a low larynx and round, even sound, but John Potter argues that pop/rock singers (and their singing techniques) actually are much closer to the 16th- and 17th-century vocal ideal: ”The forays into early music by rock singers such as Jeff Buckley and Sting reveal the potential of a speech technique to illuminate the poetry of the text and the redundancy of much early music singing pedagogy.”FN

(They also say ”it takes a brave singer to pursue this way of singing”, but I wonder if it’s not the organizers who need the courage…FN)

For many years already, Fredrik Bock and I have explored these connections in our attempt to renew the performance practice of lute songs. We have already played with the singer/songwriter format in both "Love-songs respelled" and ”Sound, sweet Airs and the Art of Longing”FN I am taking this experience with me and bringing it further here in three different cross-over projects: ”O green meadow / River”, Susanna K. Wallumrød (Vollen United), ”Messiah for 4” (Ensemble Odd Size), and ”The Oriental Winds of the Baroque”. They all investigate the links between early music and various kinds of popular music, like pop, jazz, or folk/world music.

All projects in this section can be placed in that second category of Baroque Musicians with strong connections to the jazz, folk and pop music worlds- together with.. Hans Ek and Kats-Chernin.

Ensemble Odd Size - Messiah for 4

Ensemble Odd Size and the work we do is thoroughly presented throughout the reflection.

As described in chapter 3, this has been an ongoing project for a few years and I wouldn't have thought of doing L’Orfeo by myself if it wasn't for this group.

In ”Messiah for 4”, we take a well-known work, originally written for a large ensemble and many singers, we break it down and re-create it (doing Cover versions of it, as I talk about in chapter 3 - the Music). Our work is built on our lust for looking beyond the obvious. We aim to use our knowledge about early music together with our modern preferences.

In these examples, we are experimenting with gender (I’m singing an aria associated with a very masculine bass-singer), language and folk-lore (I’ve translated the English lyrics into Swedish, and the music is influenced by Scandinavian folk music). All of which I’ve investigated in L’Orfeo.

Me:

- Baroque soprano

Usually, a clear voice without vibrato. Uneven angles. Strong colours. Flowing, but distinct phrases, sometimes embellished with trills and graceful diminutions.

- New Music Singer

Able to manage different singing techniques and needs a mind for reading complex scores. A flexible voice and open mind for intricate and enigmatic scores is also desirable.

sometimes lead me to

- Creating new music+Early music project

- Taking part in Cross-over projects (f.ex, early music+pop/folk, New music+pop/folk)

- Playing with so-called Extended Vocal Techniques

The use of text (and a little acting-singing)

The way Rolf Wallin and Helmut Lachenmann use the text ”…though what made it has gone” and ”Got Lost” are in many ways similar: they paint panic, fear and sadness, by letting the singer trip on the words, get stuck on consonants, jumping between languages. Words are chopped up into fragments. They are mixed together, into one another, over one another, becoming sounds without obvious meaning. Stuttering. Repeating. Like a Recitar Cantando of the subconscious? (Yes, this is a term invented by me!)

Even though both of them have written the pronunciation of the text very clearly (with phonetics, rhythms, notes and instructions) I’ve found it challenging to perform this music as a ”singer”. Despite all the information in the score, my body had to figure out how to actually do all the things the composers ask of me through physical experience. But, when I turned my mind into an ”actor-singer” mode, it seemed to solve those technical challenges. Adding gestures, linked to the phrases, enforced the underlying narrative and took away some of the pressure in the complexity of the music. Instead of more or less impressive sounds and Extended Vocal Techniques (i’m coming back to this term in a little while), I expressed something, for me, meaningful and physically embodied.

O green meadow / River, Susanna K. Wallumrød

"O green meadow,” was part of the same concert as "Secular Psalms" by Eivind Buene at the Ultima festival 2019, and the parameters were the same: use Strozzi's music, or get inspired by her, incorporate it in your own context, and create a new piece.

The score we received from Wallumrød was very, very clean: a simple melody over a figured bass line, with just a few hints on tempo and dynamics from which we were to form an arrangement suitable for the ensemble, similar to a score form the 17th century where we often have only a song line and a basso continuo. As mentioned, Wallumrød herself has engaged with baroque musicians in which she sings e.g. Dowland. She knows very well what kind of musicians she was composing for.FN

While practicing ”Green meadow”, there was a discussion in the group about the musical form. Since we didn’t have much time to either talk to Susanna Wallumrød, or work with her, we had to figure out how to solve some of the more unclear patches of the score ourselves. There were severe disagreements and heated arguments. Lucky for us, she is alive and just before the actual concert she could give us her own opinions on how she wanted it performed. Of course, it could have worked other ways too, but we could now make a choice based on her, the composer’s intentions. We didn’t have to guess, like we have to do in L’Orfeo.

Charulatha Mani (Griffith University)

A recent, inspiring, artistic research project I also want to refer to is Charulatha Mani’s exiting ”Hybridising Karnatik Music and Early Opera: A Journey Through Voice, Word, and Gesture”.

Our two projects meet in that we both wanted to investigate our own musical backgrounds (her’s as a karnatik singer FN - me as a classical, baroque singer) by mirroring them in apparently opposite styles and/or singing as much as possible ourselves.

One of her research questions was:

”How can an exploration of the key elements of declamation in early opera through the lens of Karnatik raga and my Karnatik voice lead to composition and performance of musico-poetic hybridity?”FN

Although her research made her investigate a genre she didn’t know very well before, and mine was about combining the different musical voices already very familiar to me, our common tool was L’Orfeo! Her research project was to sing Monteverdi as an KarnaticX singer and she even sang her way through many of the roles (even if that wasn’t her main subject). Hearing her sing Possente Spirto in her karnatic singing technique - with coloraturas and melismatic runs similar to that of a baroque singer - was quite eye opening. Hearing the well known music from the outside, from the ”otherness”, gave me the same experience as letting the characters sing each other’s texts and melodies: the very core of Monteverdi and L’Orfeo appeared in a clearer sound.

One day, Charulatha sent me a graphic score of La Music (from the Prologo - a part that I took out myself). She had written it down herself and it was very loose and open with just the necessary notes left of the original music and she asked me to sing and improvise around it:

”Many of those involved in early music also experimented with the avant-garde. The group dynamics flourished in a similar manner, with many singers steering clear fo the mainstream and experimenting with both old and new music. Like the early music movement, the avant-garde had roots in musical events earlier in the century and grew out of attempts to extend or bypass conventional singing". John Potter FN

In this live version of "...though what made it has gone", we had worked on implementing gestures and body language in the piece, with Kjetil Skøyen. This way I brought gestures into Wallin. Gestures and more Acting-Singing.

(Norwegian academy of Music 24/10-2019)

The Oriental Winds of the Baroque

Even though this project wasn’t directly linked to L’Orfeo I wanted to include it in my research process because the mixing of genres and performing baroque music with ” non-baroque musicians” - all musicians played from their personal outlook and background - opened my mind for new possibilities that became part of the final result.

It was a wish from the amazing saxophone player Rolf-Erik Nystrøm (one of the most versatile musicians in Norway. He moves between almost every single genre there is. He is as appreciated for his lyrical improvisation skills as being a performer of the avant-garde) to investigate different cultural influences on the 17th-century music scene in Europe: rhythms from North Africa, melodies from the middle east, dances from South America…

Kouame Sereba (voice and percussion) from la Côte d'Ivoire, Nils Økland (Violins, Hardanger fiddle…) with a background in Norwegian folk music, Jesus Fernandez (lute) from Andalusia, and Rolf-Erik Nystrøm (saxophone) from his own magical universe. This world music/baroque setup is similar to groups like L’Arpeggiata who also play with genres, searching for unexpected roots of the European baroque.

The Argentinian conductor Gabriel Garrido, when I worked with him and Ensemble Elyma in the beginning of the century, often talked about the unbroken folk traditions in South America and how they still influence the performance practice of European 16th- and 17th music. In South America music by Monteverdi and his contemporaries became part of a living tradition, instead of, Garrido said, Baroque music developing into Rococo, Classical, Romantic, and so on. This gave him, and us, an immediate and natural access to the 400 years old music that I experienced as very authentic, not only HIP.

This project, The Oriental Winds of the Baroque, has that same attitude. When singing Lamento della Ninfa accompanied by saxophone, Hardanger fiddle as well as a HIP-lute, I found that the ”tempo della mano” was more available to me than in a conventional setting. Maybe the unbroken lines from the 17th-century? Maybe the laid-back atmosphere?

Here is a short extract, the whole album can be found here.

Carola Bauckholt recorded and transcribed sounds from little baby Emil. The notation is very exact and the score even comes with a cd with all of Emil’s authentic sounds. The goal for the performer is to sound as much like little Emil as possible.FN

My body remembers being a baby even if my conscious mind does not, and my voice actually knows where to do find both the crying and whimpering and the exploratory and playful sounds. It is fascinating to explore the emotions these sounds stir up. And the empathy I feel for my inner baby. And I suspect the audience feels it too.

E. Again, I want to argue that I see no specific similarities between early music singing and new music (unless we choose to perform it the same way), but that there is a wish for a non-mainstream approach that draws singers/musicians like me to these extremes. That is not to say this combination is uncommon - it is not unusual FN - but I believe that it’s something else we are looking for. The Doubleness? The Otherness? The extremes!

S. But there ARE similarities? The profound essence is the same: the Music!

You breathe, and the air causes your vocal cords to vibrate and creating sound; your desire to change people's lives - if only for right now -, your deep love for music and the joy of interacting with fellow musicians. Same. The feeling that the music is more significant than us. Same. Conveying text and emotional streams of selves… SAME!

E.Yes of course. But, as I said, after looking for similarities for many years, I began to notice that this search made me an even more divided artist because the similarities I thought I was searching for were no longer there. The way of approaching the score is different, the interaction between the musicians is different, the rehearsal process is different, the audience, the text, and the words...

S. Many say that the vocal sound is similar. That it is ”instrumental” in both early and new music. That you use your voice as an instrument?

E. But why? During the 17th century, it was the instruments that imitated the voice, not the other way. The voice was the start. The Pure, human, voice.FN

I agree that phrasing, articulation and precision are more important than the sound itself (which is more desired in e.g the romantic repertoire), and that is perhaps similar in both fields, but how I phrase, articulate, am precise, is different.

I would argue that someone like Monteverdi is closer to…Andrew Lloyd Webber or Susanna Wallumrød than Lachenmann!

S. Ok! But, what about the non-Vibrato?

E. Yes, that seems to be a link. But only if we can agree that singers sang without vibrato in the 17th-century, and we can’t (as discussed a few sentences ago). There are too many sources indicating vibrato amongst singers even then. And haven’t we gotten further away from the ”vibrato question”? Vibrato is normally not an issue for me. I use it or I don’t use it, according to the piece and the emotion. But I find it interesting that many still considered non-vibrato more ”baroque” than a voice with a natural vibrato.FN

S. Where do you place yourself in the contemporary scene?

E. This is difficult, as I don’t really see me on a specific scene at all. I am a performing artist and singer with extensive classical training. I am not an inventive, improvising singer - I’m actually quite traditional, even if I am strong-headed, and prefer to do things my way.

One big difference between myself and singers like Elle and Nowitz is that they are also creative artists. In addition to being singers, they are composers who sometimes write the music they are performing. I sing from a pre-created score most of the time.

S. Do you want to compose and become a creative artist?

E. No, but I would love to be more co-creative.

S. In chapter one I asked you: "When do You feel most like yourself?" and your answer was:

"In the Doubleness - When two sides meet." But here, in this project, you seem to literally loose your footing.

E. I also said:”Or, rather, when I can go from one to the Other…I feel whole when I embrace both, but also in the space between extremes. Operating in entirely different universes… ” When I don’t have to decide my mind stays open. Karen Barad says: ”Indeterminacy is not a lack, a loss, but an affirmation, a celebration of the plentitude of nothingness.”FN

Vollen United is a flexible ensemble based on a duo with pianist Kenneth Karlsson and me. We invite different musicians from different genres and styles. In this case cellist Inga Grytås Byrkjeland and lutist Fredrik Bock.

What theories and methods did I bring from the cross-over projects to L’Orfeo?

- Reminding me of the unbroken traditions we have and using them.

- Viewing Monteverdi’s music as music from another tradition - a tradition we don’t know everything about - can broaden our minds and make us more humble.

- Merging genres opens doors to new sounds. The contact between pop and baroque is e.g especially liberating

- The necessity of breaking rules!

- Using my voice without overthinking. A simpleness. When I don’t over articulate the text, I can give space to the poetry in the words.

- The similarities between early music and pop/jazz /folk are really there.

- Finding techniques in other cultures that gave me a broader palette to work from.

- Making me aware of the different roles I, myself, already play in different settings.

- The decision to include a jazz musician (Johannes Lundberg) in the final production, thus drawing a line from thoughts and research from e.g Andrew Lawrence-King (see. chapter 4 - the music)

-

In all of the cross-over projects I’ve made conscious choices about the sound of my voice. Going away from the ”generic soprano norm” might have taken away some of the expected shine and glitter from my voice, but instead it gave me a musical freedom. Since the voice in some cases was ”unexpected” and less conventional (e.g ”Why do the nations…” from ”Messiah for 4”) I felt freer to express my own musical ideas, which was later crucial in L’Orfeo.

- A reminder of how little we get from the score. Even when we are provided with basic conditions to know how the composer wants her/his music (she is alive!), we can’t really know unless we ask. We can only guess. (I think that is a beautiful and respectful starting point.)

Theories and methods I brought from ”Emil” and ”Die Alte" to L’Orfeo:

- They are quite the opposite of 17th-century opera which offers a clear ”Otherness” to Orfeo and to Monteverdi. Monteverdi has natural freedom and playfulness I don’t find here as easy. I have to work for it.

- They create a story in sounds (”Favola in Suoni”) and make me less dependent on words not within my normal vocabulary (f.ex the archaic Italian I sing in L’Orfeo).

- I can sometimes skip words and use basic noises instead (Crying, sighing, laughing…)

- They showed me how the most primitive vocal sounds are intuitively empathetic.

- Euridice’s voice, in my performance, is directly linked to ”Emil” and Caronte’s to ”Die Alte” (although Caronte is more intense, I did found the basis of him in ”Die Alte”)

- Trusting the mirror neurons in my audience to awaken their empathy FN

- Wallin and Bauckholt are both represented in ”A tree with a name” (will be presented in chapter 7)

What I brought with me to L’Orfeo:

- My ambiguity can be used as a strength when switching between the characters and roles in L’Orfeo.

- To strive for unity in the musical duality! Or not! It can also just be respected for what it is.

- When mixing styles (as I did in L’Orfeo) I need to be able to sing with my own voice, HIP or not. Find it! Trust it!

- Be firm and decisive even in the unknown! Just go for it!

- Be aware of ”non-vibrato”!

- Mistakes in the print, might not be mistakes. Or they just might. Make them yours. Claim them!

- There are still opinions on how certain singers should sound: ignore them!

All of these projects are Dialogue between Monteverdi and other genres, styles, and composers; Dialogue between me and other musicians; Dialogue between my musical personalities. Dialogue between the brains.

They will all be directly linked to L'Orfeo or to "A tree with a name", which I will discuss in the next chapter: Touching Otherness

”However, hybridity also made itself visible in the distinctness that the music, languages and styles retained in such a confluence.”

Charulata Mani.FN

From my diary 17/9-2019

Meeting here, in the middle, not knowing how. But we are making music, and the problems might have been all my head, and only there.. Are my own contradictive perceptions of my separate musical worlds building barriers in me? Couldn’t I invent a new way of meeting them?

The others seem to do fine, but I am torn. I am two of my personalities at the same time, and they don’t really agree. This concert is a struggle. I am making myself vulnerable by adding this to my artistic results, but if anything, I need honesty and vulnerability

Beyonce and Beyond, Rebecka Ahvenniemi, DNO (Bergen), 9/3 2018.

Musical direction - Stephen Higgings, Stage directions - Sjaron Minailo

Singers: Elisabeth Holmertz, Lore Lixenberg, Halvor Festervoll Melien

Extracts from "...though what made it has gone" (Rolf Wallin) And "Un feu naissant" (2. couplet) (Joseph Chabanceau de la Barre

Especially in learning Possente Spirto, I often asked myself how Charulatha would have sung it. Trying to imitate refined and flowing ornaments of a Karnatic singer.

This is an old human, who’s lost words and memory. What she has left: Sighs, moans, muffled words and pain. Like with Emil, the nerves from my vocal cords send signals to my most instinctive feelings. The sounds from my voice make my body happy, sad, frustrated, tired. FN

I know that it’s painful to listen to as well. To hear a baby cry. A confused, sad woman who cannot find her own self anymore. It hurts to listen to and it hurts to perform it.

There is nothing refined in my voice - just immediate rawness. Performing this, I must forget my classical training, but I don’t experience anything ”extended” in this - it is just very natural.

How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace, and bring glad tidings of good things!” (trans: Hur ljuvliga är ej stegen från dem som kommer med bud om frid. Och bringar glädje till jorden, ja glädje till vårt folk)

Wikipedia on The doctrine of the affections (italian ”affetti”): ”also known as the doctrine of affects, doctrine of the passions, theory of the affects, or by the German term Affektenlehre (after the German Affekt; plural Affekte) was a theory in the aesthetics of painting, music, and theatre, widely used in the Baroque era (1600–1750)”