Tallinn Harbour:

rhythms of a road-to-sea bottleneck

and the effects on the city

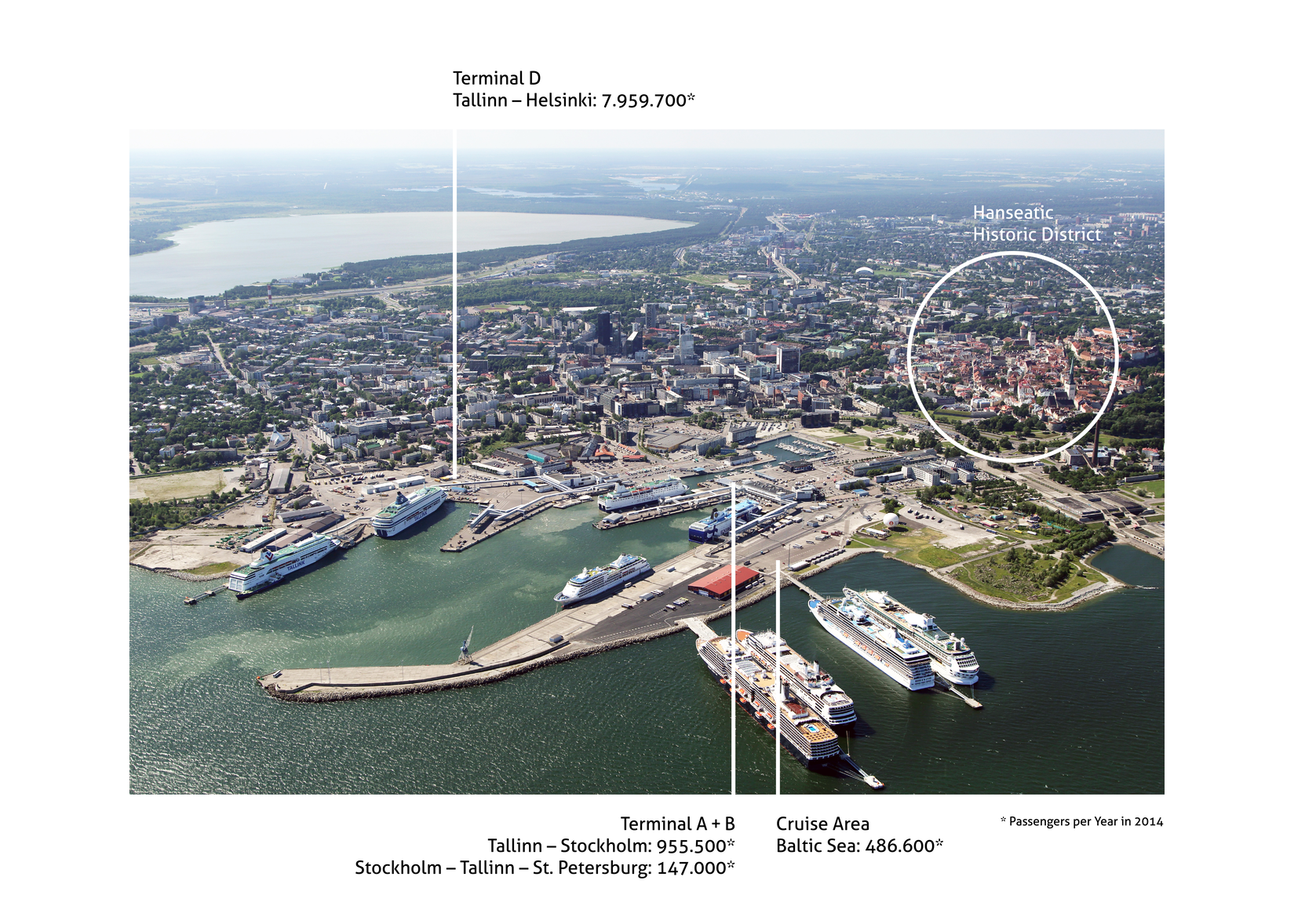

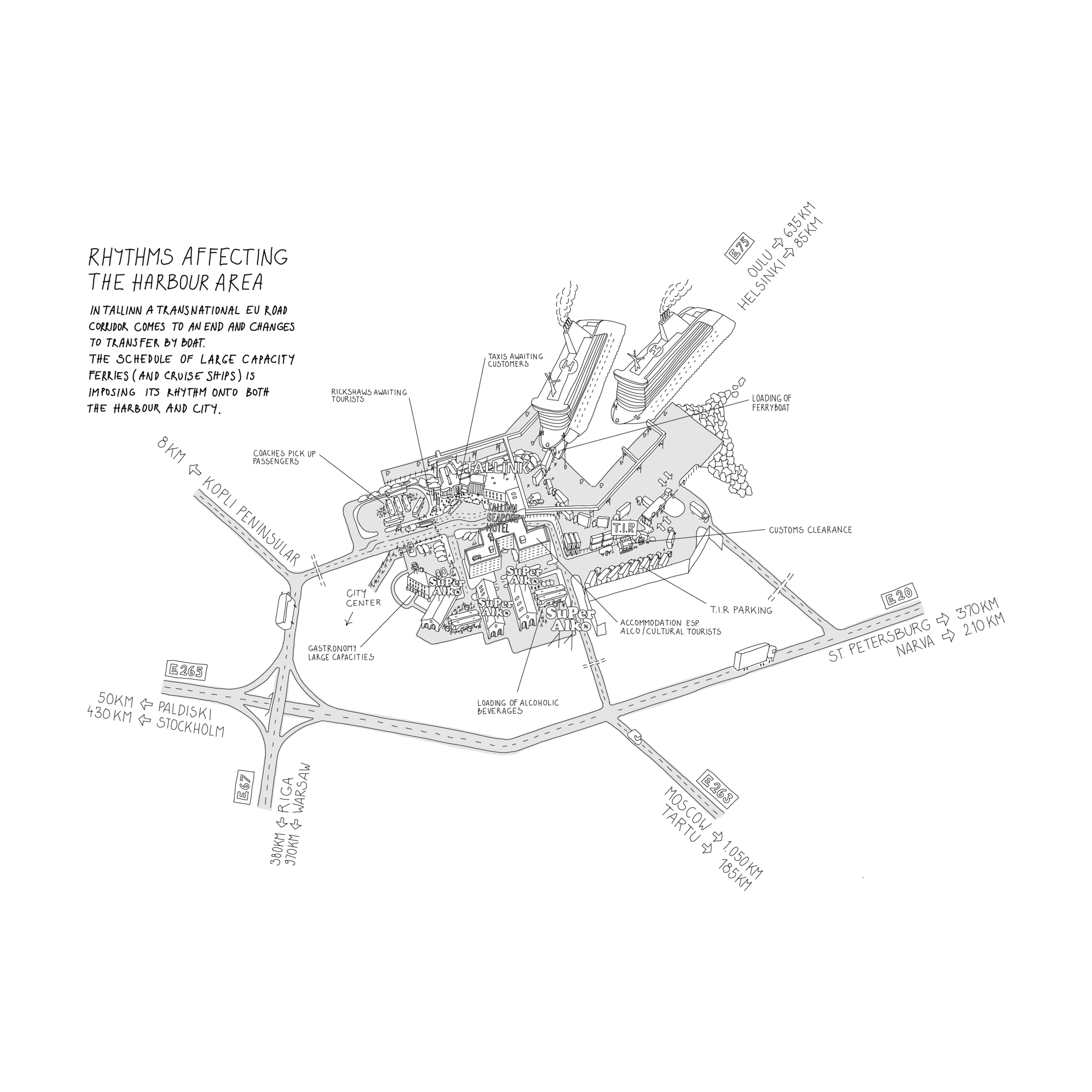

Between Tallinn in Estonia (part of the Soviet Union before the fall of the Iron Curtain) and Helsinki in Finland (part of the capitalist West), a continuation of the pan-European road corridor is in place in the form of a highly efficient regular ferry connection. Pedestrians, cars, buses, and lorries are transported across the Baltic Sea in huge ships that leave every three hours. In both cities three major highways arrive at big terminal complexes, which represent bottlenecks that narrow traffic to the limited capacities and decelerated speed of the vessels, which are delivered over to the harbour on the opposite side of the Baltic bay, where vehicles are redirected to the road corridors once again.

The enormous income, price, and purchasing power differentials between Estonia and Finland drive the flow of mobility: while 15 per cent of the Estonian population try to make their fortune as labour migrants in Finland, groups of Finns travel as tourists to Tallinn to consume and shop cheaply – above all, for alcohol. The routes and routines of these mobile subjects have an enormous influence on the city because they stimulate the building of new infrastructures (larger ships, new terminals, hotels, bars, souvenir shops, and supermarkets, many of them specialising in alcoholic drinks), while service providers of all kinds want to take advantage of the traffic flow: bus drivers, taxi drivers, mobile kiosks, and even beggars, appearing and disappearing with the rhythm of arrivals and departures of the big boats. But the intensive influx of tourists has also strikingly altered the streetscape of the historic city centre, with the most visible signs being the amber jewellery shops, themed ‘Hanseatic-era’ restaurants, and pubs screening football matches.

Because of its history as a picturesque, well-maintained Hanseatic city, Tallinn in summer is a popular destination for cultural tourists and cruise-line passengers. The Russian population that settled during the Soviet period – many today without a passport – have been pushed into low-wage jobs and ‘grey area’ markets because of post-socialist de-industrialisation and discrimination. Nowadays the Russian market next to the train station – Balti Jaarma Turk – is regarded as one of the most popular ‘authentic’ attractions for souvenir hunters. In contrast with almost everywhere else, the noteworthy building boom in Tallinn has not even been interrupted by the housing mortgage crisis. The reason for this lies in the fact that many of the elegant, newly built projects have been financed mainly by Scandinavian companies and investment funds with whose help wealthy Russian investors were enabled to safely anchor their vulnerable capital in EU harbours.

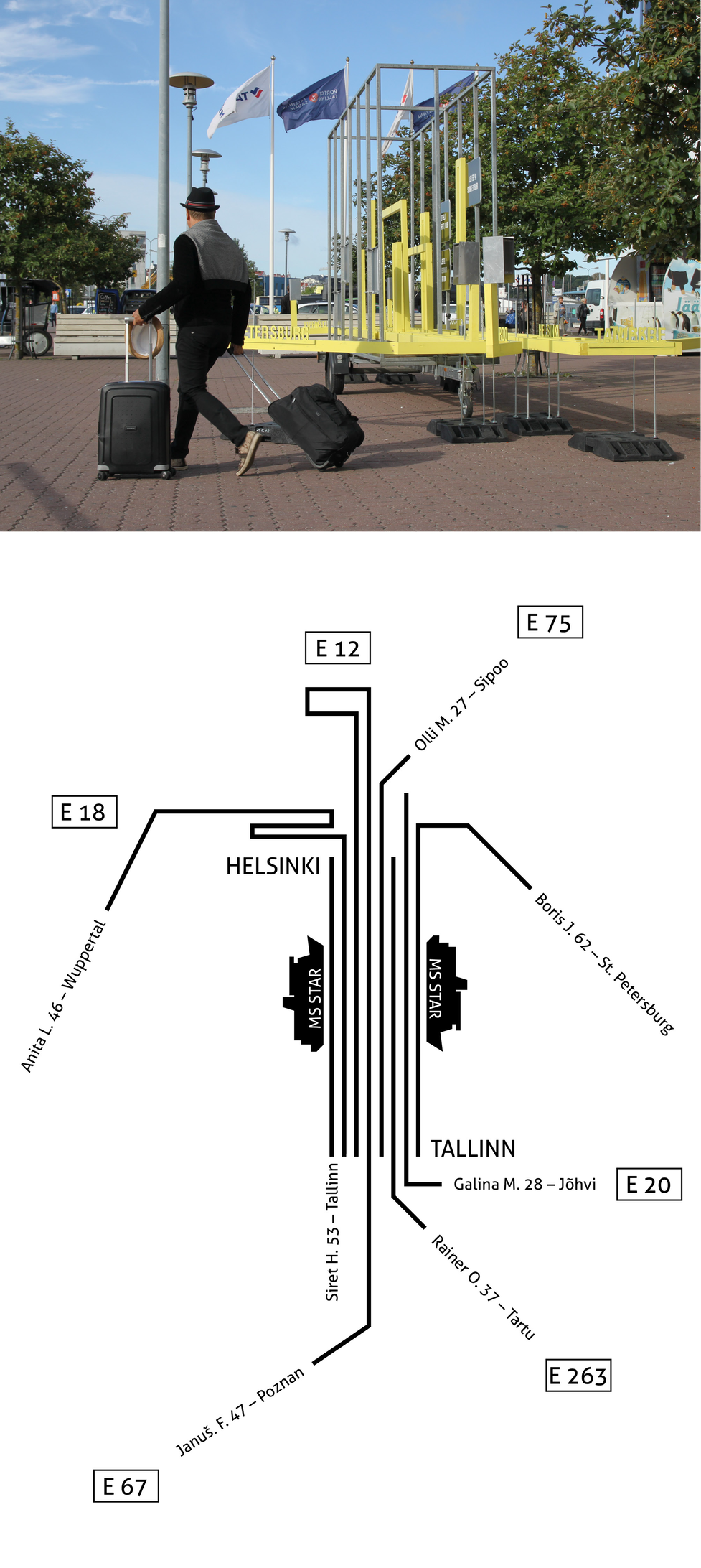

Installation in front of Terminal D at the Port of Tallinn: a contribution to the satellite programme of the Tallinn Architecture Biennale

TAB 2015 Self-Driven City

Boris J., 62

Investor and manager from St. Petersburg, Russia, who controls his real estate investments in Estonia every second month.

Galina M., 28

Skilled primary school teacher, ethnic Russian, currently a waitress, from Jõhvi, Estonia, who works in shifts at a bar on the ferry boat after having lost her initial job.

Januš. F., 47

Truck driver from Poznan, Poland who transports cargo between Poland, Finland, and Russia. He passes by the harbour once a week.

Rainer O., 37

Construction worker from Tartu, Estonia, who, due to the quite remarkable differences in earnings, works as a labour migrant around Helsinki.

Anita L., 46

Export manager from Wuppertal, Germany, who visits clients in Scandinavia and the Baltic realm over three combined trips per year.

Olli M., 27

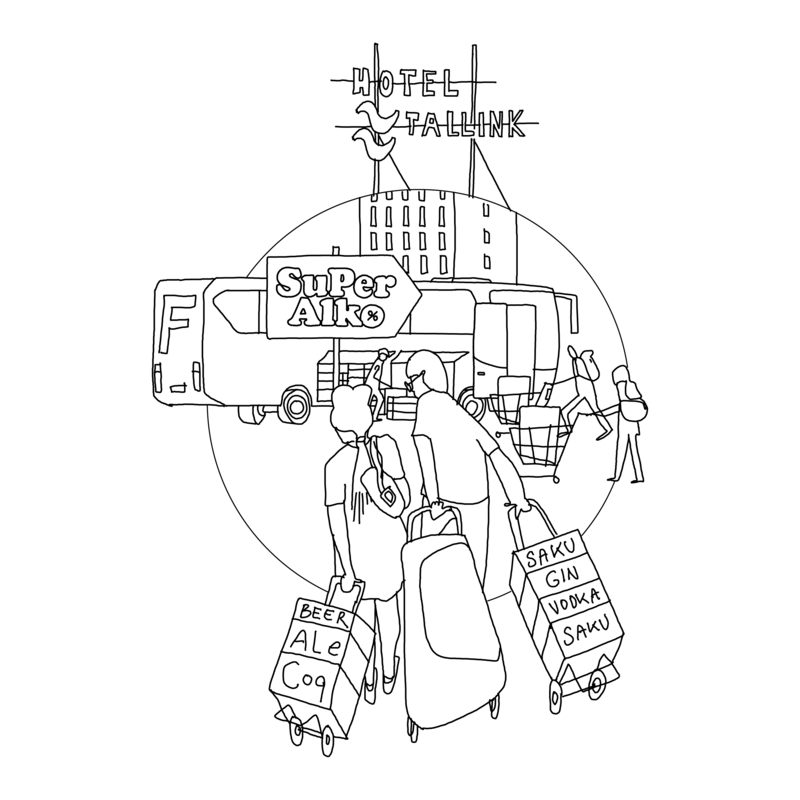

Car mechanic and his friends from Sipoo, Finland, who three times per year travel to Tallinn to stroll around the bars of the old town of Tallinn and to purchase as many alcoholic drinks as allowed. The significant difference in prices enables them to refinance the costs of the trip.

Siret H., 53

Accountant from Tallinn, Estonia, who frequently travels to Helsinki to purchase objects at flea markets in Helsinki and resell them at Tallinn’s Telliskivi flea market twice per month.

A speaking passenger-network diagram

In September 2015 we employed the cultural capital of the Tallinn Architecture Biennale to convince the harbour administration of Tallinn to support our project and realise our first large-scale intervention in public space. We obtained permission to park our trailer in front of Terminal D. With almost eight million passengers a year, it is the most frequented terminal connecting Tallinn and Helsinki. Here we expected not only to attract a large audience to visit our intervention but also to meet a variety of people and speak about their mobility experiences.

In this context the trailer did not function as a large-scale drawing board but as the supporting structure for a three-dimensional network sculpture. The yellow wooden beams represented an abstract map of the routes and paths of selected individuals who use the ferry connection – both their voyage across the sea and their landside trips from their departure point to their target destination. Via built-in loudspeakers passers-by could listen to the individuals’ narrations, which introduced different motives, rhythms, rituals, and routines (represented by the sound files to the right).

These micro-narratives relate both to the individuals’ biographies and to more general historical, political, and economic transformations of the Baltic area, thereby interrelating transnational mobility flows and place-making in very specific sites. Moreover, these stories address sociocultural/economic differences and effects that cause, among other things, (labour) migration and cross-border consumption. For example: an ethnic Russian teacher who works in shifts at a bar on the ferry boat after having lost her original job; a Russian businessman from St. Petersburg who checks his real estate investments in Estonia every second month; a Polish truck driver who passes by the harbour once a week; a construction worker from the south-east of Estonia who works as a labour migrant around Helsinki; a sales representative of a German company who visits clients in Scandinavia and the Baltic area; and a group of young Finns who frequently travel to Tallinn with a reduced group ticket to stroll around the bars of the Old Town of Tallinn, before returning with their shopping carts to bring back as many alcoholic drinks as the carts allowed – the significantly lower prices easily enable them to refinance the costs of the trip.

The represented paths and narratives are based on or refer to thirty episodic interviews with staff and passengers of the ferry line, conducted by our Estonian research partner, Tarmo Pikner, either onboard the boat or in the waiting areas of the terminal building. Fragments of the real experiences of many different people were rendered anonymous and consciously merged into a reduced number of seven fictional characters, which still offer a wide range of travel biographies but do not overburden the capacities of the people passing the installation. To enhance the grade of abstraction, each of the soundtracks was spoken by a radio presenter.

This installation was intended not only as a representation of the final results of our Tallinn research but also as a visually attractive trigger for collecting additional expertise from mobile actors. During the set-up process we could experience live onsite how the arrival times of ferry boats dramatically increased the number of taxis, buses, and rickshaw drivers along with the presence of small-scale vendors and beggars. The seemingly over-dimensioned asphalt desert of parking lots became completely filled with vehicles for a short time. Once the parking lots were empty again, the consumption zones alongside the beaten paths of tourists became crowded: the souvenir shops and bars in the Old Town, the shopping malls along the inner ring, and the many alcohol supermarkets and hotels near the harbour.

For the installation itself the chosen site turned out to be less appropriate for our efforts: although there were an enormous number of passengers passing by, they were far too busy heading for a taxi or bus or following the crowds on the path towards the city centre. The only people who had time to speak with us were the terminal staff smoking a cigarette outdoors, passengers who had missed the boat, and people waiting to offer services to arriving passengers. For example, whenever a boat arrived several rickshaw drivers turned up and switched on certain signature tunes to catch the attention of passengers. They had time to watch us building the installation over the course of several days. One of them, who arrived first each day, introduced us to his precarious work life: he was a young, deprived ethnic Russian from far outside Tallinn, who did not even have an apartment in town – too expensive, he said. Of course, he knew the schedule of the boats by heart, as he does with all other events in town. He works a tight schedule as long as the high summer season lasts. At night he sleeps – no more than a few hours each day – in his vehicle, parked on the waterfront or in a vacant warehouse nearby. He often takes a nap while awaiting the arrival of a ferry. The vehicle does not belong to him. He has to pay rent to the company that has drawn a monopolist licence to exclusively offer these services in Tallinn and in other European cities.

Drunken Finns, who had missed their ferry and had to wait for the next, explained the prices of alcohol to us in detail and the best choices to increase their virtual income by purchasing drinks in Tallinn that would cost more than double in Finland, thereby refinancing the costs of the trip and more. But we also learned that this specific carnivalesque ritual is not limited to lower-middle-class men: there were also whole families, each member pulling an unfoldable trolley packed with alcoholic drinks back on board. And when buses leave the boat and pick up the passengers – mainly elderly tourists – at the big parking lot in front of the terminal, they first drive directly to one of the many supermarkets – with names like SuperAlko Store – and fill the huge boot with boxes of drinks, before they start the sightseeing trip.

On the other hand, merely the attempt to get the permission of the harbour administration to use this site for the installation opened doors to insider knowledge: about the enormous revenue made from tourism and the high-risk dependency of Tallinn on low tax, low wages, and cheap service and consumer products, especially alcohol, in comparison with Scandinavian countries. Some drinks are even imported from Finland by boat to be sold much cheaper and brought back by the Finns. The manager also introduced us to historic details of the harbour, which was transformed from an entirely closed-off cargo terminal in Communist times into an open terrain used solely by ferry boats and cruise ships, a promising site for real estate developments between the Old Town and the harbour front, and thus a perfect vehicle for mobilising the flow of capital, virtually travelling parallel with the ferry lines.