Road*Registers – a logbook of mobile worlds

In September 2016 we opened an exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna to disseminate our research methods and findings in the growing community of arts-based research at our host institution – and also to communicate the project to a wider audience in Vienna. For this exhibition we appropriated the notion of ‘road registers’ from Kathleen Stewart (2014), which we considered both a perfect title and a more open and inclusive framework for an exhibition, combining our own research with the work of others.

We conceived this exhibition as an interim report about this research project in the form of an art exhibition. This decision had the added advantage of freeing us from the discipline, linear argumentation structure, and textual reading methodology implicit in a scientific paper. Furthermore, the works that inspired our theoretical and methodological approach are not only discretely quoted in footnotes and sources but also prominently displayed in key positions in the exhibition space. This allowed for connecting lines of sight and interactive relationships while presenting suggestions for possible pathways through the different chapters, thereby varying the narrative structures.

Artworks as representational mediums in exhibitions are subject to similar laws to contributions to written scientific publications. The choice of media and the structure of the work privilege certain substantive aspects and discriminate against others, hence they simultaneously include and exclude. For this reason, we tried to define the methodological approaches as broadly as possible.

The order in which the three central case studies in the research project are shown in the three large exhibition spaces corresponds with a mapping that follows the real geographical situation – from south to north. Visitors enter the exhibition through works concerned with the ‘Bulgarian region’, then go through a ‘corridor’ to come to the ‘Vienna area’ with its historical reference projects, and finally arrive in the ‘Baltic region’, which is a cul-de-sac. Here they turn around and wander in the opposite direction through the exhibition – through the ‘Vienna area’ back to ‘Bulgaria’ and the exit.

The representation of these three case studies consisted primarily of large-scale diagrams and abstract maps of pathways, networks, and urban archipelagos along the transnational routes we drove along in our Ford Transit. There were also objects we brought back ‘from the field’ on our research journeys. However, we also wanted to (literally) give a voice to the social actors by employing semi-documentary video works of other artists whose large-format projections open up the three large exhibition rooms almost like windows while expanding the geographical and substantive viewpoints, too.

Starting with the SOMAT network of lorry drivers formerly employed by what was the state monopoly for transnational goods transport in Communist Bulgaria, we follow via video Corridor #8 by Boris Despodov, an ambitious but never realised road construction project running from the Black Sea coast to Albania. A presentation of the history of the international bus station in Vienna (from which the most frequented route leads to Serbia), is complemented by Logbook Serbistan, a video by Želimir Žilnik showing the fate of refugees who, before the huge wave of people in autumn 2015, came from North Africa, Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan and got stuck in Serbia. The conclusion is formed by the rhythms of the Tallinn ferry terminal and its connections to Helsinki, which dominate the whole seaport, and the video Forgotten Space by Allan Sekula and Noël Burch, which opens up a window on the container ship traffic spanning the oceans of the world.

The exhibition also included supplementary works and contributions from artists, art historians, journalists, architects, and anthropologists (made as part of research ventures and trips), which were of vital importance for the curators and their research project. Key examples of the historical methods of research and representation, which have, in the meantime, inspired numerous generations, were the image-oriented universal language by Otto Neurath and Gerd Arntz (Groß 2015), small, self-published artists’ books documenting typologies of architecture along the roadside by Ed Ruscha, and those by the Las Vegas Studio run by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. In 1968, using the semiotic focus of road users, Venturi and Brown, together with students from Yale University, investigated the architecture of the entertainment economy that had developed along one street: the strip in Las Vegas (Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour 1972).

The presented artworks spanned methodological extremes – from critical and analytical distance to empathetic participation. For instance, Matthias Klos’s search for a location from which to make photographic overviews of the surroundings of a major road and its infrastructures automatically generates distance. This is aesthetically beneficial for the photos of the logistics landscape but detrimental to establishing social contact in the field. Gabriele Sturm’s decision to be a ‘participant observer’ in the field by accompanying a lorry driver for a 3,000 kilometre journey leads to the opposite – unavoidable closeness, intimacy, and empathy but also a loss of aesthetic control. The temporal dimensions in these works encompasses both long-term investigations, such as Mindaugas Kavaliauska’s photo documentary observations of the systemically determined delay in personal motorisation in Lithuania, which, inter alia, led to a huge second-hand car market after the fall of the Iron Curtain, as well as short-term, purely material appropriations like the ‘cut-outs’ of an asphalt road surface with traces of its use by Sonia Leimer. These isolated fragments from urban spaces are open to multiple interpretations on archaeological, psychoanalytical, political, and poetic levels.

A further curatorial aspect of the project was the attempt to sound out shifts in meaning in different contexts. In contrast to the auratic white cube of the exhibition space at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, the works of the participants were also staged in the Stop and Go research laboratory situated in an active road-to-rail cargo terminal – a location with practical connections to the subject along with an ‘authentic’ atmosphere and a great amount of mobility expertise. An extensive print and video library was also made available to visitors there.

ROAD*REGISTERS: a logbook of mobile worlds

An exhibition as part of the WWTF research project Stop and Go: Nodes of Transformation and Transition with contributions by Gerd Arntz | Noël Burch | Boris Despodov | Thomas Grabka | Martin Grabner | Michael Hieslmair | Kurt Hörbst | Helmut Kandl | Johanna Kandl | Emiliya Karaboeva | Mindaugas Kavaliauskas | Matthias Klos | Sonia Leimer | Vesselina Nikolaeva | Katarzyna Osiecka | Zara Pfeifer | Tarmo Pikner | Lisl Ponger | Maximilian Pramatarov | Ed Ruscha | Rimini Protokoll | SO MAT-Archive | Allan Sekula | Tim Sharp | Gabriele Sturm | Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown | Tatjana Vukosavljević | Ina Weber | Želimir Žilnik | Michael Zinganel

30 September–6 November 2016

x hibit Academy of Fine Arts, Schillerplatz 3, A-1010 Wien

Stop and Go. Project Space, Nordwestbahnhof, Taborstraße 95, A-1200 Vienna

Curatorial team: Michael Hieslmair | Michael Zinganel

> More photos from the exhibition ROAD*REGISTERS

> A catalogue of the exhibition ROAD*REGISTERS can be previewed and downloaded here

The node and network of the Vienna International Bus Terminal

Escape as a travel motive was far from being the research focus of our project. We viewed escape as one of many motives and modes in a continuum of mobilities (Hall and Williams 2002), which is characterised above all by the daily transport of goods and people along these corridors, although it also includes the transport of legal and illegal goods as well as persons with or without papers, whose motives range from tourist interests and trade and business travel to migration and escape (Bauman 2000).

In 2013, when we submitted our research project, refugees from Syria were not yet a sensational theme for the mass media – even though, by that point at the latest, thousands were already on their way. Instead, populist politicians and media were still spreading doomsday scenarios of a migrant invasion from Bulgaria and Romania, which had been full EU members since 2007, even though their citizens could only work legally in Germany or Austria from 2014, after the end of the seven-year transition phase. The route of this imagined invasion corresponded with the so-called Balkan route or, more precisely, the web of roads traversing South-East Europe. In our project we did not intend to support this thesis of an invasion – quite the contrary – the aim was to document the normality of a multi-local existence, the continuous experience of being on the road and becoming accustomed to a life in transit. In this light, especially for those who don’t possess their own vehicle, minivans and transnational bus services are the preferred means of transport, which also provide capacities to transport substantial amounts of goods.

Vienna International Bus Terminal represented an important hub for these types of bus passengers. In our view, this terminal was also interesting because it is currently situated at a very – at first glance – unattractive location under a highway bridge and looks like a non-place par excellence. Due to the dominant image until recently of bus travel as a means of transport for low-income migrants from South-East Europe, the bus stations were gentrified away from their previous locations next to inner-city train stations (Haberfellner 2014). Our thesis was that this bus terminal, in fact, was not merely a space without history; rather, countless mobile actors with mobility and migration experiences come together here at busy times, exchanging with one another, and their individual stories also reflect the transformations in the regions along their routes. We also considered the bus drivers of the international lines to be important actors of knowledge transfer, as their scheduled bus stops are nearby, they have known many of their regular customers for years, and they know what can be transported across which borders and how. Additionally, the drivers from the private Austrian bus company Blaguss, which operates this terminal, usually have migrant backgrounds, have escaped from the acts of war and ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia or their economic consequences, or are children of former guest workers or refugees.

The traffic web of transnational bus routes that start or intersect here represents the connections of destination and source regions of tourists, former guest workers and their relatives, commuters, and labour migrants. Currently, the most frequented strand leads via the A4 eastern highway to Hungary, either in the direction of Romania or via Serbia and on to Bosnia and Bulgaria. In these buses one can naturally also find persons who are regarded as unwelcome in Vienna’s majority population: beggars, prostitutes, thieves, and people without valid papers (Tatzgern 2016). For the most part, however, these buses carry those service personnel whose modestly paid work facilitates the above-average quality of everyday life for Vienna’s middle class in the first place.

© Photo: Lisa Rastl 2015

Section of the road corridor from Vienna to the Austrian-Hungarian border, beginning at the Vienna International Bus Terminal, showing several urban archipelagos developed around logistical hubs along the highway …

© Photo: Peter Trautwein 2015

Documentation of the side programme: a public guided bus tour visiting several nodes of transnational mobility and migration between Vienna and the Austrian-Hungarian border.

© Photo: Martin Grabner 2015

Vienna International Bus Terminal strangely located underneath a highway bridge – the point of departure for transnational bus connections operated on regular services.

© Map: Hieslmair | Zinganel

The network of international bus connections with Vienna at its centre. Most notable are the many stops in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe.

The map is redrawn from the timetable data on bus connections and estimated numbers of passengers provided by the management of the Vienna International Bus Terminal; however, there are many further smaller bus lines departing from and arriving at other, often informal bus stations.

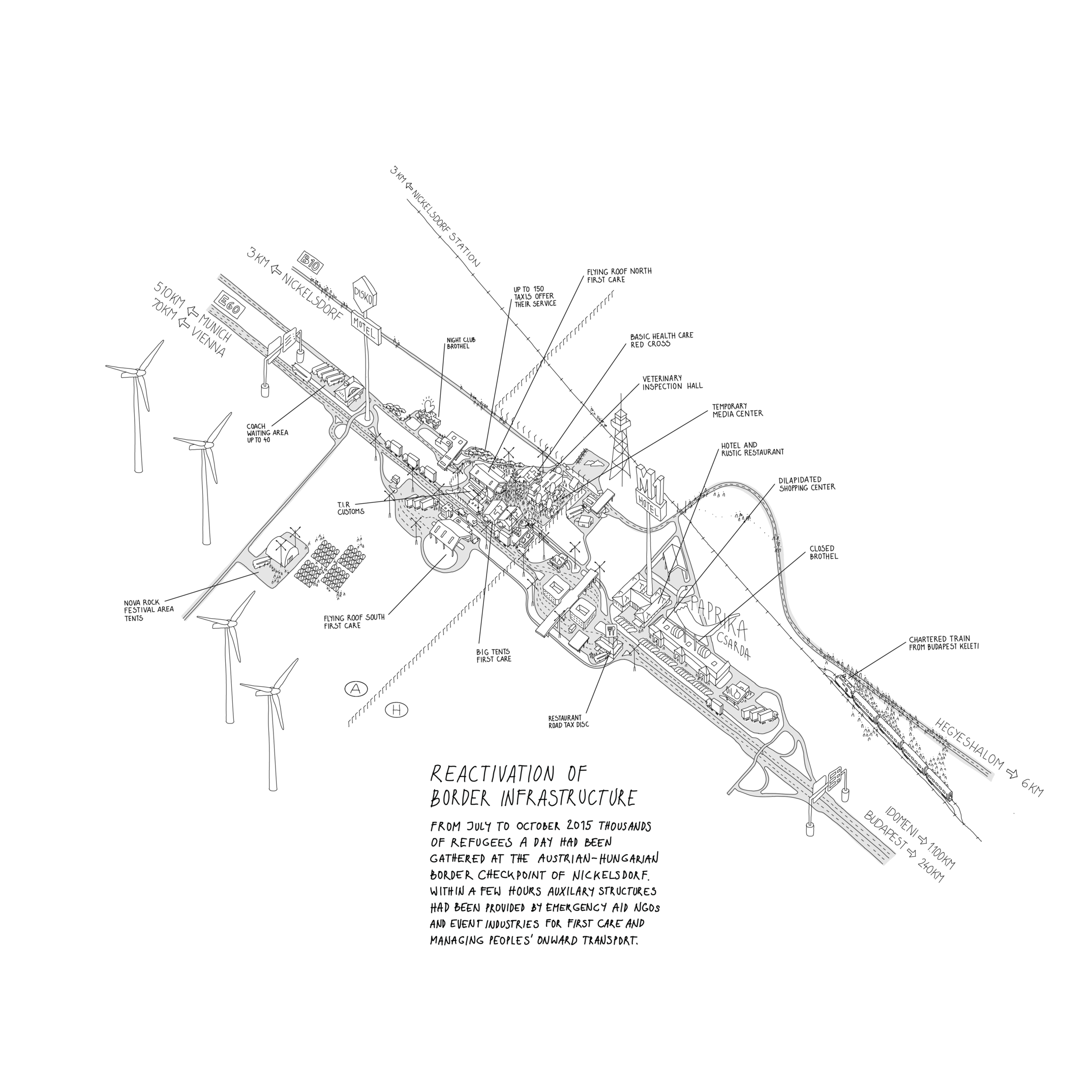

The re-activation of the Austrian-Hungarian border station during the ‘wave’ of refugees in autumn 2015

Irrespective of the refugee crisis, the transformation of the border crossing between Austria and Hungary and the history of the small border municipality of Nickelsdorf would in itself be worth its own research. The current road network had been gradually developed and improved, and the traffic volume shifted to this new route. The old road led right through the village, past small old customs houses and the tollgate, then past a street with pubs and stores bustling with activity. But the new modern border crossing was constructed far outside the municipality and finally complemented with a fully fledged highway in 1996. While the former border village went silent, the new border crossing with its highway entrance and exit ramps on both sides of the border and its more modern control facilities evolved into what seems to be an arbitrarily densifying agglomeration of streets and building complexes – an urban archipelago typical of the modern mobility landscape. Several petrol stations, hotels and motels, restaurants and markets, some partly designed and branded as theme parks (Paprika), night clubs, brothels and betting shops, kiosks and truck parks settled along the new route, touting for the best location and subjecting themselves – especially on the Hungarian side – to tough predatory competition. In our research project, however, we had stipulated different emphases, different case studies, had found other border crossings along our routes more important, so for the time being we had no free capacities available.

The unforeseeable dimension of the wave of refugees in late summer and autumn 2015 threatened to completely overshadow every discourse on mobility and migration – including our research project as well, which was now deemed particularly topical. We decided to incorporate the Nickelsdorf border crossing – which we had already passed through many times on our research trips – more strongly in our investigations. To this end, we organised a one-day public bus excursion in December 2015 in the framework of a workshop; the tour started at the Vienna International Bus Terminal and visited other hubs of mobility and migration and urban archipelagos along the A4 eastern highway before arriving at the border crossing. Mayor Gerhard Zapfl then guided us to all the places in Nickelsdorf where just two months earlier the tremendous influx of refugees had to be handled without any preparation.

Up to this point, we had regarded the border crossings along the routes of our research trips – as with other stops – simply as thresholds in the mobility landscape. We had overlooked that, out of fear of the controls, there was expertise to be sold concerning evasion of the controls and that the differences between the availability and costs of goods and services produce booming border economies on both sides, which attract mobile actors and are used by those in transit (Schlögel 2005; Konstantinov 1996).

Initially, we hardly realised that custom and border police are important employers in border regions. In almost every family in the border villages there was at least one member who had found work in this realm or still worked there (Zapfl 2016a). A smuggler who doesn’t personally know at least one of the border officers and their work roster and doesn’t know the level of smuggled goods they will tolerate or the costs is incompetent. Hence, the reliability of these social networks influences the choice of smuggling routes to allow as many people as possible to have their share in the added value.

This applies to the smuggling not only of goods but also of people. During the refugee crisis in late summer 2015, the majority of the refugees did not take, as one would expect, the regular and low-priced bus connections from Turkey to Bulgaria and then, within the EU, on to Vienna. Many were led along the much more dangerous route across the Mediterranean to Greece, and from there overland to Macedonia and Serbia. But most of those who made it to Bulgaria were again smuggled out of the EU into Serbia and then back in the EU via Hungary. This seemingly unnecessary traversal of two EU external borders cannot be explained alone by the fact that the border between the two neighbouring EU states, Bulgaria and Romania, is exceptionally well-controlled; rather, it also involves the networks that have been growing for many years along the Serbian-Bulgarian and Serbian-Hungarian borders, which had at last gained a key significance during the Yugoslavian wars.

From Hungary the refugees passed the border crossing near Nickelsdorf. Since Hungary joined the EU in 2004, it has been an inner-EU border crossing, and since 2002 also a crossing between two Schengen states; hence, from Hungary on, borders are essentially open and controls are only carried out randomly in exceptional cases. Accordingly, the infrastructure for border controls has been gradually reduced to a minimum, and the gigantic parking lots for trucks became wastelands or were adapted for other purposes.

Mobilisation instead of control

From July 2015 a growing number of refugees were picked up along the stretch of the A4 eastern highway between the border and Vienna. Smugglers had brought them from Hungary across the border to Austria. On 27 August a refrigerator truck was found on the service lane of the A4, close to the Designer Outlet Parndorf shopping centre, twenty-two kilometres from the Austrian-Hungarian border. Seventy-one dead refugees were found inside. They were brought for forensic examination and identification to a border-crossing cooling hall, which had originally been set up to control imported food. Just a week later, from 4 September, while the corpses were still stored at the site, thousands of refugees in Hungary started arriving each day at the border crossing. Initially, they were transported from Nickelsdorf to Vienna West Station in trains chartered from the Austrian Federal Railways – later with buses and taxis – and then taken further on to Germany. On 16 September the military took over the Austria-wide coordination of the transport logistics from the border crossing to the train stations and emergency shelters. To this end, one officer requested buses from a private company, which were more flexible in bringing refugees directly to the respective destinations (Mayerhofer 2016). As mentioned before, many of the bus drivers originated from the Yugoslavian successor states, and their families themselves had personal experiences of migration and escape.

The parking lots and border infrastructures, which had hardly been used since the end of the EU and Schengen border, were also reactivated to handle the stream of refugees and were complemented by temporary structures from both the emergency aid and event sectors. The large parking lot in front of a former border zone disco on the Austrian side was now used for chartered buses, which were then sent to the border one by one. The manager of a rock festival near the border opened his backstage hall and the festival meadow as a camping ground to accommodate the refugees. On the highway the truck parking lot in front of the roofed control zone and the area under the flying roof were adapted for first aid measures. Later on two large heatable tents were erected on the parking lot. These were never put into operation because on 15 October the refugee flow on this route came to an end. The ‘closing’ of the border between Serbia and Hungary proclaimed by the Hungarian government and celebrated in the media now redirected the masses to another strand of the Balkan route.

During these critical days the responsible government politicians in Vienna vanished from the scene. Confronted with the emergency situation and lack of instructions, the help organisations and supervisory bodies, including those of the state, which had gathered at the border decided to respond on their own authority. They neglected the guidelines of the Dublin II Regulation by only trying to provide for the mass of refugees, while keeping them in constant movement to prevent escalations in front of running TV cameras, rather than by controlling them (Zapfl 2016a).

Austrian ‘welcome culture’ primarily pertained not to their refugees but to their preferably conflict-free further transport to Germany. Buses were the best-suited means of transportation to keep the enormous stream in controlled motion and to prevent frustration among refugees (or at least keep it within limits), while those responsible in the background could still negotiate the respective destinations of the buses. In autumn 2015 the reactivated border crossing was thus not a space of demobilisation but one of mobilisation. It revealed a state-tolerated strategy of ‘mobilising away’, which Austria shared with other countries along the refugee routes (Benigni and Pierdicca 2016).

In October 2016, upon completion of our research project and exactly a year after the influx of refugees, we repeated our bus tour to Nickelsdorf: There we found new, more solid control infrastructures built upon the large truck parking lot on the premises of the border crossing; a big facility comprised of containers with booths to check the personal data of those wanting to enter the country; another container facility for accommodating detained persons without an entry permit – a de facto custody prison; and prefabricated barrier elements that, if needed, could be assembled within a few hours into a solid fence with barbed wire topping on both sides of the border – measures, in the words of Nickelsdorf’s mayor, that ‘will hopefully never be needed’ (Zapfl 2016b).

The experience of the refugee crisis was drastic for the small border village: the events brought the previously insignificant and easily overlooked municipality into the world’s press, and the concerted efforts had – according to the proud mayor –a very positive effect on the village’s sense of community. Thus, the autumn of 2015 will definitely play an important role in the collective memory of the village in the future. The mayor emphasised that the temporary state of emergency caused by the mass flight of refugees was in no case unique in the history of the small border village: during the Hungarian crisis in November 1956, 180,000 refugees passed through Nickelsdorf, and in 1989, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, 40,000 exhausted GDR citizens had to be tended to. Also the escape routes that changed since October 2015 were not new: the stretch from Serbia to Croatia, through Slovenia to Austria across the Spielberg border crossing, has been a part of mobility and migration history since the 1960s as a route for guest workers. Many of the bus drivers, who in autumn 2015 transported the new refugees across Austria, had once entered the country on these very roads.

Today it is not entirely true to say that the entire Balkan route is ‘closed’. As was the case before the so-called ‘crisis’, wherever escape helpers have logistics and functioning networks available, sometimes including state supervisory bodies, goods and people without the right papers will cross the borders – together with countless other mobile individuals, including ‘research explorers’ like ourselves.

© Drawing: Hieslmair | Zinganel

The drawing is based on conversations with Gerhard Zapfl, mayor of the border-village of Nickelsdorf, who was in charge of the management of forced migration and first aid for migrants arriving at the station. Actually, the map was redrawn in several stages, after the mayor found important elements missing each time. Later we also used this map as the basic structure for an animated graphic novel.

To see the video visit Method 2: Mapping