„(…) A není horší křivdy na zemi

než otročiti v cizí poddanosti:

Buď stokrát zdráv, kdo svými pažemi

v čas boje národ toho jařma zprostí. (…)“

“There’s no worse injustice on Earth

than to slave away in foreign subjugation:

Praised be a hundred times the one who,

in the time of war, will free the people from the yoke. (...)”

February 16, 1936, Prague

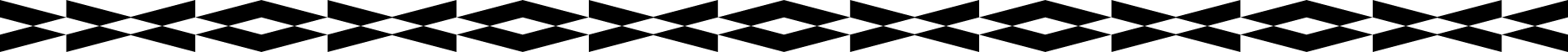

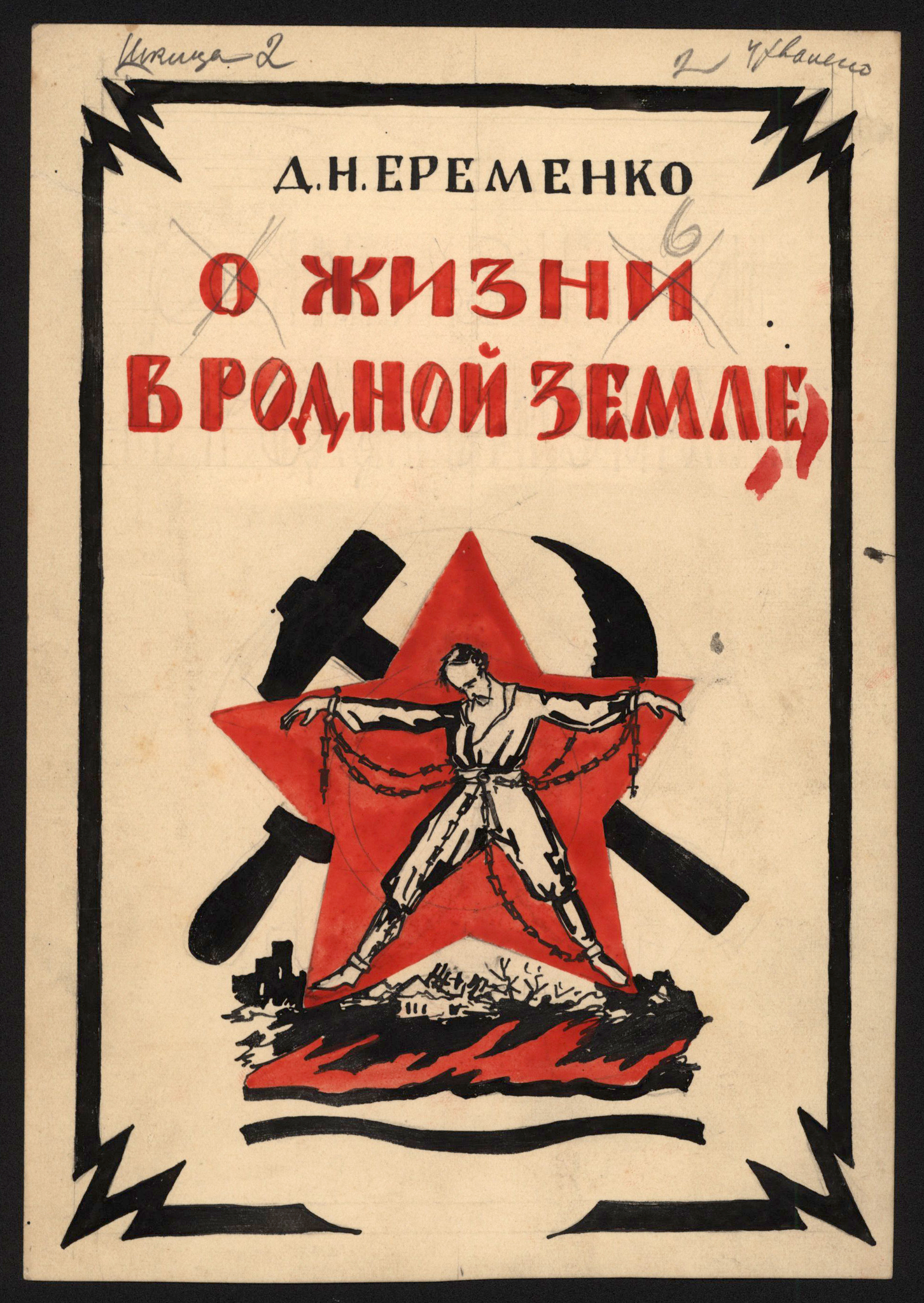

Spyrydon Cherkasenko (1876 Новий Буг, Херсонська область – 1940 Praha), Osvoboditel, in: Marie Omelčenková (ed.), T. G. Masarykovi ukrajinští básníci, Prague: Vydavatelství Česko-ukrajinská kniha, 1936, translated by František Tichý, typesetting and graphic design by Robert Lisovský, p. 6. The aforementioned book presented poems by Ukrainian authors “originally from the Greater Ukraine, living in Prague”, but also by poets who lived in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, an autonomous part of Czechoslovakia in the interwar period.

The current situation, in which the pressure of the Russian war of aggression on the territory of independent Ukraine has forced part of the Ukrainian population into neighboring countries to the “West”, resembles the situation of interwar Czechoslovakia, when the fledgling democratic state and surrounding countries received refugees from the “East”. From around the end of World War I, between 1917 and 1920, the Russian Empire was in disarray following the events of the Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian Civil War. As a result, anti-Bolsheviks, the so-called White Russians, Belarusians, Armenians and a large community of Ukrainian exiles who had failed in their attempt at independence, were forced to flee to the “West”.

Ukrainians had sought to establish an independent Ukrainian state since the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917: the Ukrainian War of Independence lasted from spring 1917 to autumn 1921. In 1922, Ukraine was incorporated into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and gained its independence only in 1991, after the dissolution of the USSR. Between 1919 and 1939, the southwestern part of present-day Ukraine, with Uzhhorod as its center, was part of Czechoslovakia; or more precisely one of five self-governing territories (Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia). This part of Subcarpathia or Transcarpathia, depending on the “center” from which we view it, also became part of the Soviet Union after World War II.

The Czechoslovak government headed by president Tomáš G. Masaryk,[1] minister of foreign affairs Edvard Beneš and the prime minister Karel Kramář, a well-known Slavophile, launched their so-called Russian Aid Action in 1921, aiming to assist refugees from the Russian Empire and Soviet Union in their assimilation and the continuous development of Slavic science and culture. Thanks to this program, Ukrainians made their way to Czechoslovakia,[2] while the relief action focused on the development of educational capacity and support of students.[3]

Most Ukrainians that came to Czechoslovakia maintained “anti-Communist and anti-Soviet stances”,[4] which were further reinforced by reports of the horrors of Holodomor, a man-made famine induced in Soviet Ukraine by the Bolsheviks in 1932–1933, which constituted genocide.[5] In addition to the anti-Communist and anti-Soviet ideological stances that were characteristic of the Ukrainian exiles in general, the opinions of individual members of the Ukrainian community differed and “showed a great diversity – from social democratic to nationalist with authoritarian tendencies”. Their beliefs and values were also diverse – from Orthodox and Greek Catholicism to Judaism and Protestantism to various forms of Marxism or atheistic humanism”.[6] This ideological spectrum would have been nurtured in an intellectual center for Ukrainians, the Ukrainian Free University that transferred to Prague in 1922 and which, among other disciplines, focused on Ukrainian studies (historical and philological contexts) and ethnographic and art-historical studies. The cultural and educational institutions that significantly helped shape the identity of Ukrainian exiles in Prague also included a post-secondary art school called the Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts in Prague (est. 1923)[7] and the Museum of the Struggle for Liberation of Ukraine (est. 1925).[8] A large amount of the surviving documentation related to the Ukrainian interwar diaspora and associated institutions is stored and processed by scholars at the specialized Slavonic Library, now part of the National Library of the Czech Republic in Prague.

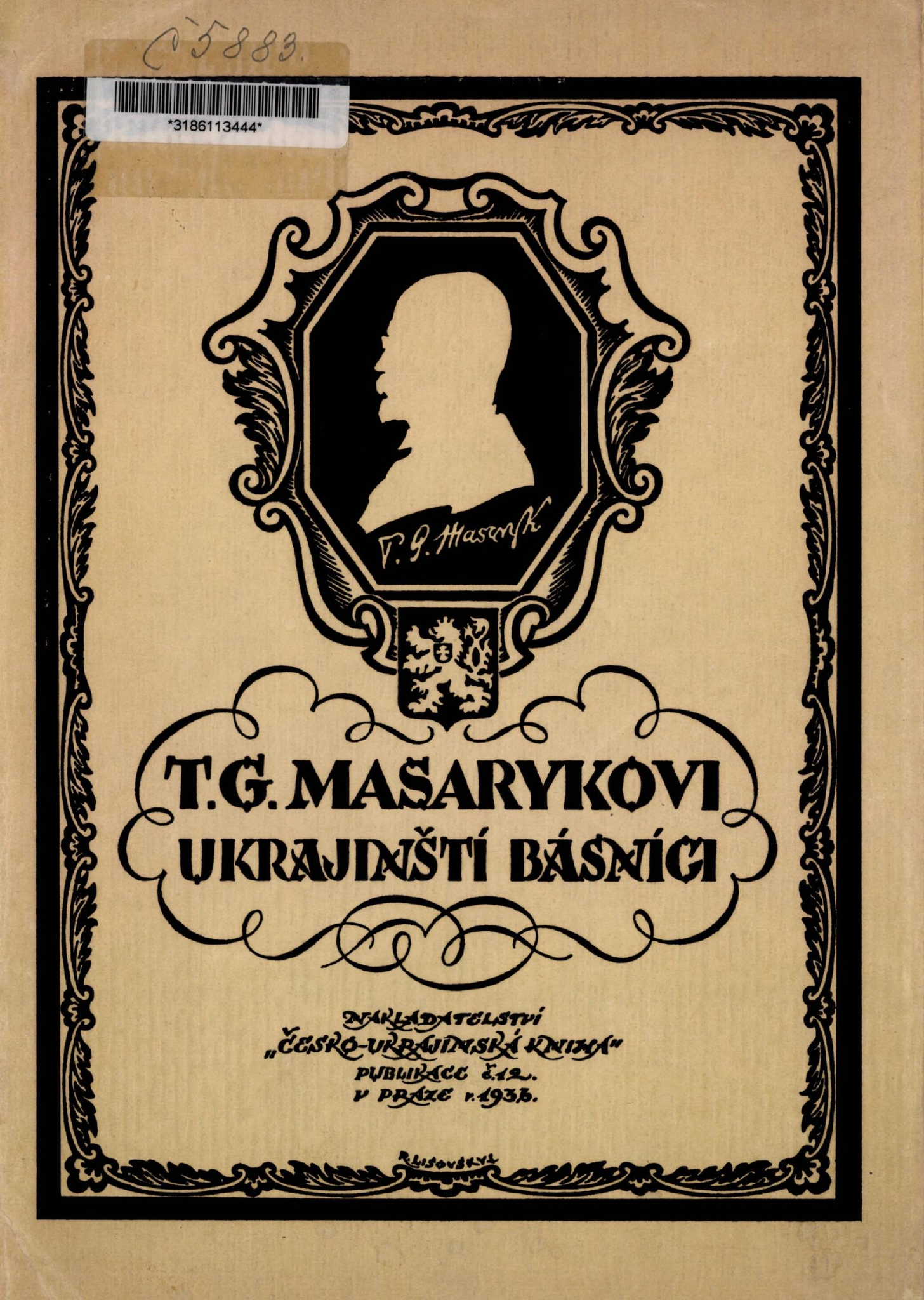

The Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts in Prague / Українська студія пластичного мистецтва and the Museum of the Struggle for Liberation of Ukraine / Музей визвольної боротьби України cooperated closely; both institutions were directed by Dmytro Antonovych (*1877 Kyiv – †1945 Prague).[9] Antonovych, a cultural historian, had resided in Prague since 1921 and actively participated in the newly formed structures of the exiled Ukrainian government and in the emerging diplomatic corps. He was a prominent figure in the field of social sciences and focused deeply on the history of Ukrainian art,[10] which he placed particularly in the European cultural matrix.[11]

He was involved in the development of the contemporary Ukrainian painting that strived for a specific form of modernism in the context of Prague exile, one that would connect Ukrainian “national” traditions with the current tendencies of the Western European fine arts, French and German in particular. The Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts, the art school established in Prague, was designed as a locally autonomous complement in relation to other art institutions in Ukraine, namely in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Lviv and Chernivtsi.

In a 1924 catalogue, Antonovych explained the reasons behind the founding of the school and the need for a Ukrainian art school in exile: “Ukrainian artists founded a distinct Ukrainian university of fine arts not because the Czechoslovak colleges, overcrowded as they are, could not accept all the young Ukrainian artists residing in the Czechoslovak Republic, but for different, deeper reasons that lie in the very essence of art. (...) Every nation differs in its manifestations of artistic creativity from others. (...) Ukrainian artists, having temporarily lost their native soil, were forced to establish their own artistic headquarters in Prague, which, in turn, led to the formation of the Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts in Prague. (...) The Studio is a Ukrainian art center in Prague, unconstrained in its direction and tendencies, the work of the center is Ukrainian, independently of whether the artists want it. (...) The Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts in Prague is the biggest center of Ukrainian art beyond [Ukraine’s] borders.”[12]

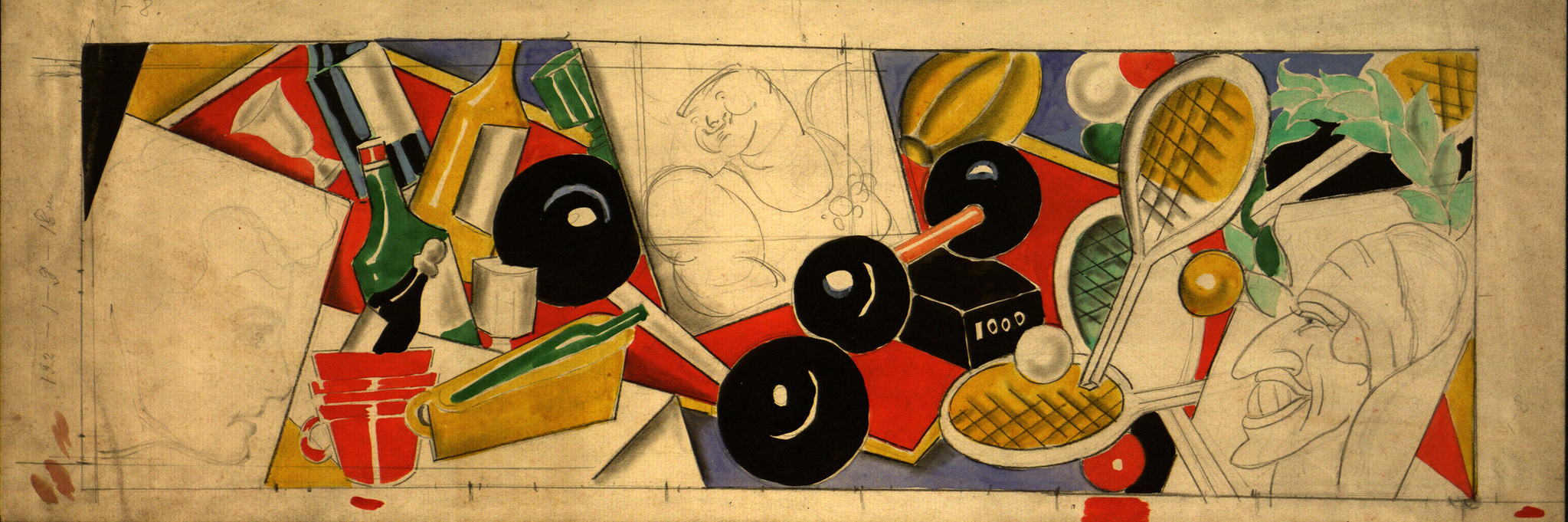

In addition to the director, professor Dmytro Antonovych, who taught art history, the staff included Serhei Mako, an artist trained in France, who taught drawing and painting; painter and sculptor Ivan Kulets; Ivan Mozalevskyi, who taught graphics and decorative arts; Kost Stachovskyi, who taught sculpture; Ivan Mirchuk, who taught aesthetics; and Fedir Slusarenko, who taught classical archaeology.

According to Serhei Mako, an influential educator at the school, the Ukrainian cultural identity had to be symbiotically intertwined with European modernity but should not identify with its predominantly Western European relation without reservation. As Rumjana Dačeva explains, Mako founded the international art group Skythy in the 1930s, built upon the “theory of Eurasian unity as an antithesis to the expansive Germano-Romanesque culture”.[13] Myroslava Mudrak, an art historian originally from Ukraine, now active in Ohio, has focused on Ivan Kulets as the painter and sculptor who connected French synthetic cubism with the Czech artistic group of “Tvrdošíjní”,[14] but also with the fairly strict aesthetic theories of formal harmony and the geometric canon of body proportions taught by Kulets’s colleague Ivan Mirchuk.[15] Kulets’s lectures were attended by Natalia Gerken-Rusova, Sofia Zarytska, Yuriy Vovk, Oksana Liaturynska, Petro Cholodny Jr., Mykola Krichevsky and Pavel Hromnytzky. The Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts, which provided education in the fields of fine and applied arts and architecture and was known as the “Ukrainian Academy” by contemporaries, continued in Prague until the 1948 coup d’état. Today, the Slavonic Library houses a unique collection of Ukrainian art from the first half of the twentieth century, primarily works by the educators and students who were associated with Prague and the Ukrainian academy.[16]

The Czechoslovak-Ukrainian ties of the interwar period manifested in the regions of the former Subcarpathian Ruthenia too. At the time of the First Czechoslovak Republic, there were no specialized art schools at the level of traditional art academies. The closest art academies could be found in Budapest or Lviv, and from the 1930s onwards, artists went to study in Prague or Bratislava. In 1927, painters Josef Bokšaj and Vojtěch Erdélyi[1] founded a public drawing school (Publyčnaja škola malovanja) in Uzhhorod, aiming to raise a new generation of Subcarpathian painters, educated in the European tradition and brought up in the spirit of Czechoslovak patriotism. Fedir Manaylo, a painter from Uzhhorod, studied at UMPRUM in Prague under the supervision of professor Zdeněk Kratochvíl in the 1930s. After his return to Subcarpathian Ruthenia, as a great collector and connoisseur of folk art, he combined these influences with a modern painting style in his own work.[2]

Both Erdélyi and Bokšaj were active in Uzhhorod and regularly participated in exhibitions outside of Subcarpathian Ruthenia, in Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia (Prague 1929, 1937; Brno 1928; Bratislava 1936), and were perceived as representatives of interwar Czechoslovak art, although their paintings were not purchased by the Modern Gallery (the institution preceding the National Gallery in Prague). In 1936, the Group of Fine Artists of Subcarpathian Ruthenia held an exhibition in the pavilion of the Slovak Art Forum in Bratislava, in which several female artists participated. The exhibition included works by Samuel Welber Sándor Beregi, Anton Boček, Josef Bokšaj, Jaromír Cupal, Ladislav Šarpataky, Jan and Vojtěch Erdélyiovi, Markéta Gottlieb-Blumová, Ladislav Kaigl, Andrej Kocka, Alžběta Lanczy, Maria Rejlová, Božena Rodová-Šašecí, Jolana Sárkanyi, Milada Špálová-Benešová, Alojz Šubrt, Josef Tomášek, Julius Virágh and Jaroslav Zajíček.

The folk art of Subcarpathian Ruthenia was an important object of research and tourist interest. In terms of the politicized ethnography of the fledgling Czechoslovakia, it was believed that the Subcarpathian land and its folk art preserved authentic relics of the Proto-Slavic people’s culture. Embroidery, folk costumes and wood carvings were therefore studied for the roots of Slavic identity. The study of the original geometric cross ornament (krivulka) represented a significant part of the ethnographic research, while Subcarpathian embroidery was considered evidence of the oldest ornamentation in Czechoslovakia. Modern reinterpretations of Proto-Slavic designs were part of the register of motifs of the representative national style used freely by the UMPRUM architects and ornamentalists in the First Czech Republic: Josef Gočár, Pavel Janák, František Kysela, F. H. Brunner and others.[3]

The ethnographer and teacher Amalia Kožmínová was one of the first Czechoslovak “missionaries” to work in multiethnic Subcarpathian Ruthenia.[4] She lived in the area, documenting it, and wrote a fascinating report on folk art. Part of her collection was presented at a major exhibition held in 1924 in the Museum of Applied Arts in Prague, titled “Art and Life of Subcarpathian Ruthenia”. The collection of embroideries from the region was presented in 1928 as “an eternal spring of water of life of the national culture and the Slavic tribe” at the International Congress for Folk Art in Prague and later came into possession of the National Museum.

The population of Subcarpathian Ruthenia was multiethnic and therefore multilingual. It consisted of Rusyns, Russians, Ukrainians, Hungarians, Jews, Romanians, Germans, Romani people and, after the incorporation into Czechoslovakia, Czechs and Slovaks as well. The Czechoslovak representation had been vocally reinforcing the Slavic identity against Germanic and Hungarian dominance and thus supported primarily the Rusyn “East Slavic” culture. Notably, such nationalist galvanization took place in a country whose inhabitants did not infer their identity from nationality nor language, but primarily from religious denomination and belonging to a manor. The modernization of Subcarpathian Ruthenia during the Czechoslovak era was largely understood as a form of aid directed from the Prague “center” toward the eastern “periphery”. Although Czechoslovakia invested heavily in local infrastructure, transportation, education and health care, guiding the centralized, government-led modernization with good intentions, in some ways Czechs were demonstrating their superiority over the people of Subcarpathian Ruthenia.[1] That is why the contemporary post-colonial discourse critically points out the fact that not even Czechs could completely avoid the pattern of social, geographical and ethnic hierarchization in the interwar period and often approached their eastern compatriots as representatives of the civilized West dealing with the backward “Orient”.[2] However, the local population today mostly retains a positive image of the “Czechoslovak” interwar era, stereotypically associated with progress and development in the collective memory.

The culture of interwar Czechoslovakia unquestionably benefited from the intellectual elites and the “high culture” of the artists that came from the “Greater Ukraine” and formed a distinctive Ukrainian diaspora, active in the academic sphere, in Prague and other Czech and Slovak cities, as well as from the Uzhhorod school of painting and deeper knowledge of the folk culture and craft of the population of Subcarpathian Ruthenia.

Lada Hubatová-Vacková