Solomiya Pelykh / Соломія Пелих (2003) lived in Kyiv before the war. Although her interest lay in art, she began to study philosophy. After the beginning of the Russian occupation, she first hid with her relatives and later decided to travel further in Europe. She was accepted to UMPRUM following a normal admission procedure and has been studying sculpture there since 2023. As a budding artist, she draws on her previous study of philosophy and interest in anthropology. She sees her artistic journey as research focused primarily on the position of traditions and religion in contemporary society.

In her view, it is impossible to come from Ukraine and not reflect on the topic of war. Despite the dramatic events that saw her brother conscripted into the army, she feels she is following the right path. After she completes her studies, she would like to return home to foster the culture in the region. Our interview took place online, as Solya was staying at a cottage near Kyiv with her family.

KATEŘINA KLÍMOVÁ’S INTERVIEW WITH SOLOMIYA PELYKH, CONDUCTED VIA EMAIL, SEPTEMBER 2024

Kateřina Klímová: Solya, where are you right now?

Solomiya Pelykh: I’m not far from Kyiv, at our cottage. I come here about every six months.

KK: What were the circumstances surrounding your arrival in Prague and your start at UMPRUM?

SP: I didn’t want to leave. When I studied philosophy in Kyiv, I lived alone, yet in the same city as the rest of my family. When the war started, my mom wanted to me to move back with them. I was hiding with them. We spent several weeks in Poland too, but we returned to Ukraine. I didn’t have anyone abroad, just an ex-boyfriend in Spain. In the end, I went there and stayed for six months. Then I moved to Budapest to stay with one of my friends. From there I went to see Prague and UMPRUM. I immediately felt that this was the place I’d like to be at, I liked the emphasis on freedom and individual expression.

I submitted my application at a time when the initial wave of refugees had already passed and there were no special internships for Ukrainian students. I took regular entrance exams among other applicants.

KK: And what studio did you apply to?

SP: Painting. But the examiners recommended Sculpture, so I went there in the end. I had few works in my portfolio, and I didn’t even hope it could work out. I didn’t expect anything.

KK: How were you received at the school?

SP: It was great. Everyone was nice and supportive already during the exams. Although the atmosphere was very competitive, others helped me with the translation to English. And during consultations, heads of the departments explained something to me in English and eventually everyone switched to English for a much longer period of time.

KK: And how do you reflect on your studies at UMPRUM in the context of your personal journey? Do you feel you’re in the right place?

SP: Yes, that’s what I feel. I’ve always wanted to pursue art, but studying modern art back home isn’t possible. Art Schools in Ukraine are still influenced by the curriculum from the times of the Soviet Union. That’s why I wanted to study abroad. I believed that it could be a means of grasping the world.

KK: Did you study any art program in Ukraine before the war?

SP: No. I only studied philosophy. For two years. I prepared my portfolio for UMPRUM in several months.

KK: That was a very bold move.

SP: Yes. I definitely didn’t expect I could be accepted.

KK: And when you enrolled in the school, were you trying to imprint themes of war and nationality into your work?

SP: Well, I’ve only been here for two terms and I’m just about to start my second year. But both of my works are linked to war, albeit indirectly. In the work I titled Památník kolektivního zranění (Collective Trauma Memorial), I reflect on how trauma is passed on to subsequent generations. Considering what effect starvation had on Ukrainians in the 1930s – when the survivors carried pieces of bread crusts in their pockets out of fear, and even their children then saved every penny – how will the ongoing war events mark Ukrainians and their future generations this time?

KK: As I browsed through your portfolio, it seemed to me that there are many references to traditions and religion in your works. Is that right?

SP: Yes, I reflect on them. Initially, I have projected, quite naively, mostly my own experience and feelings. Later, I wanted and still want to focus on generalization of these feelings in society. I am very interested in anthropology, national folklore, symbolism, original techniques and in how war has transformed local society. I view art as a research tool.

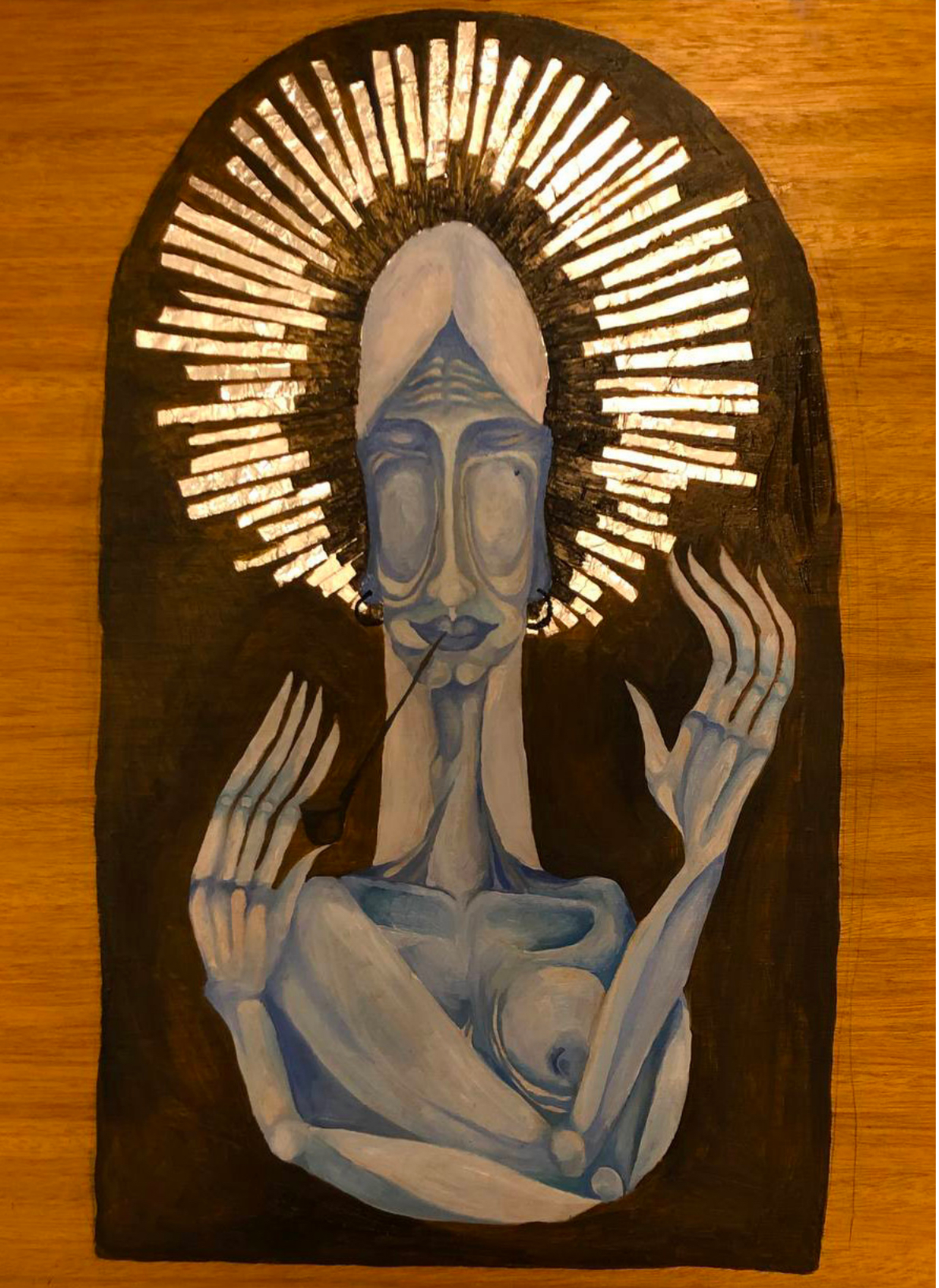

For instance, a certain phenomenon emerged among Ukrainians with the war; they have been acting on a whim. Those who wanted to get married, got married, others didn’t hesitate with divorces. As a result of the war, they suddenly began to believe in God, or vice versa, became atheists. I tried to project this into a piece called The New God, where the imaginary god is embodied by a carton of cigarettes. This came to me in summer 2022, when I overheard a conversation of two girls at the train station. One of them said that “a pack of cigarettes now gives me more hope than any god”. The work is conceived as this god’s icon.

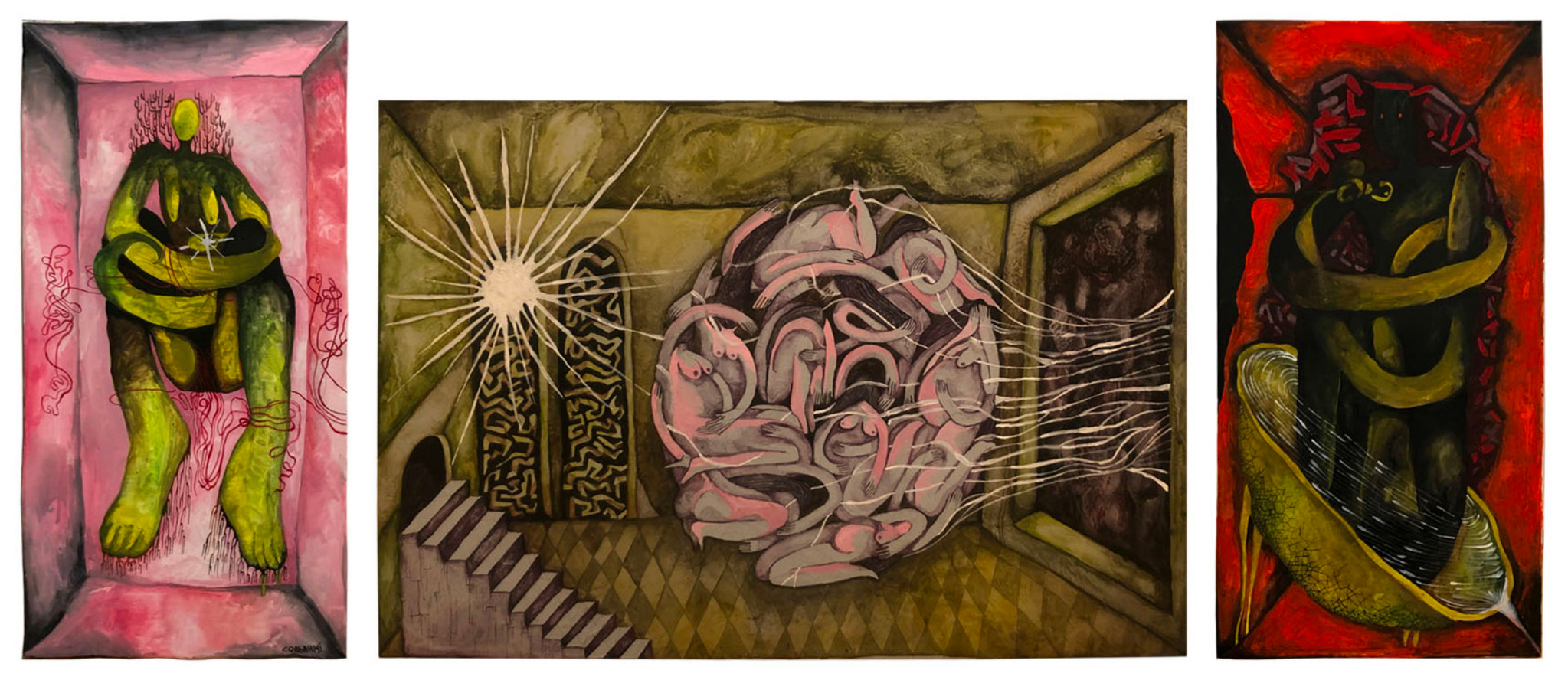

In my Eidos triptych, also an earlier work, I tried again to capture the anxiety of the time we had been hiding in air raid shelters, so it’s a very personal work. I named the canvas cycle Eidos, because it attempts to capture the essence or concept of anxiety and confinement.

In another work, I try to capture the idea that freedom is collective, and I allude to the Maidan revolution that took place when I was 10.

KK: Do you plan to continue working with these topics?

SP: I think it is impossible to be an artist from Ukraine and not reflect what’s happening over there. My exact focus is what’s changing. First, it was primarily my and my family’s experience. My brother and friends fight in the war, and we’re worried about them.

The experience of a lost home is also crucial. And also the guilt that one feels when they’re not in Ukraine with others, but hiding in a foreign country.

KK: I can’t even imagine such feelings and experiences.

SP: But sometimes we also experience and hear positive stories that bring a sudden burst of happiness: like when the brother of one of my friends returned from captivity. However, sometimes sudden grief strikes too.

Various news stories come in, sometimes joyful, sometimes sad, and everyone is trying to maintain some kind of life-war balance to withstand the unexpected events. It is important to navigate one’s own way through all this. For me, that means participating in various protests and using art as a medium to talk about war.

It is important to remind ourselves that even the bad can lead to something good. That’s what I imprinted into Sunflower. Have you heard of that story that began to spread after the start of the war, about a Ukrainian grandmother that approached Russian soldiers and offered them sunflower seeds to put in their pockets? So that at least sunflowers grow from them, when they die?

KK: Yes, I saw a meme like that on the internet.

SP: I think we need such stories. It is important to see meaning and hope in this. My work is more of a material test, but the message is hopefully obvious. Instead of seeds, there are embracing figures.

After all, I wanted to say something similar with my second end-of-term project that I named Dolor, which is Spanish for pain. In Ukraine, we suffer daily merely from the information we receive and the context we live in. I tried to create a Virgin Mary icon in these objects and tried to convey suffering unromantically, with respect and as a precious part of being human. Because all this pain means we’re human.