Systems >>

2. Parsimonia

3. EMP Triangle

4. Sinew0od

>> Patches

1. TCP/IP: NIME

2. TCP/IP: Sestina

3. TCP/IP: Reconciliation

4. Re-patching Bach

5. Triangular Progressions

6. Sinew0od for Bass Clarinet

7. Sinew0od for Halldorophone

8. Sinew0od for Buchla

Publications >>

3. Live Coding the Global Hyperorgan

© Mattias Petersson, 2025

Method

Technically, the re-patching process of the Chaconne involved the following steps:

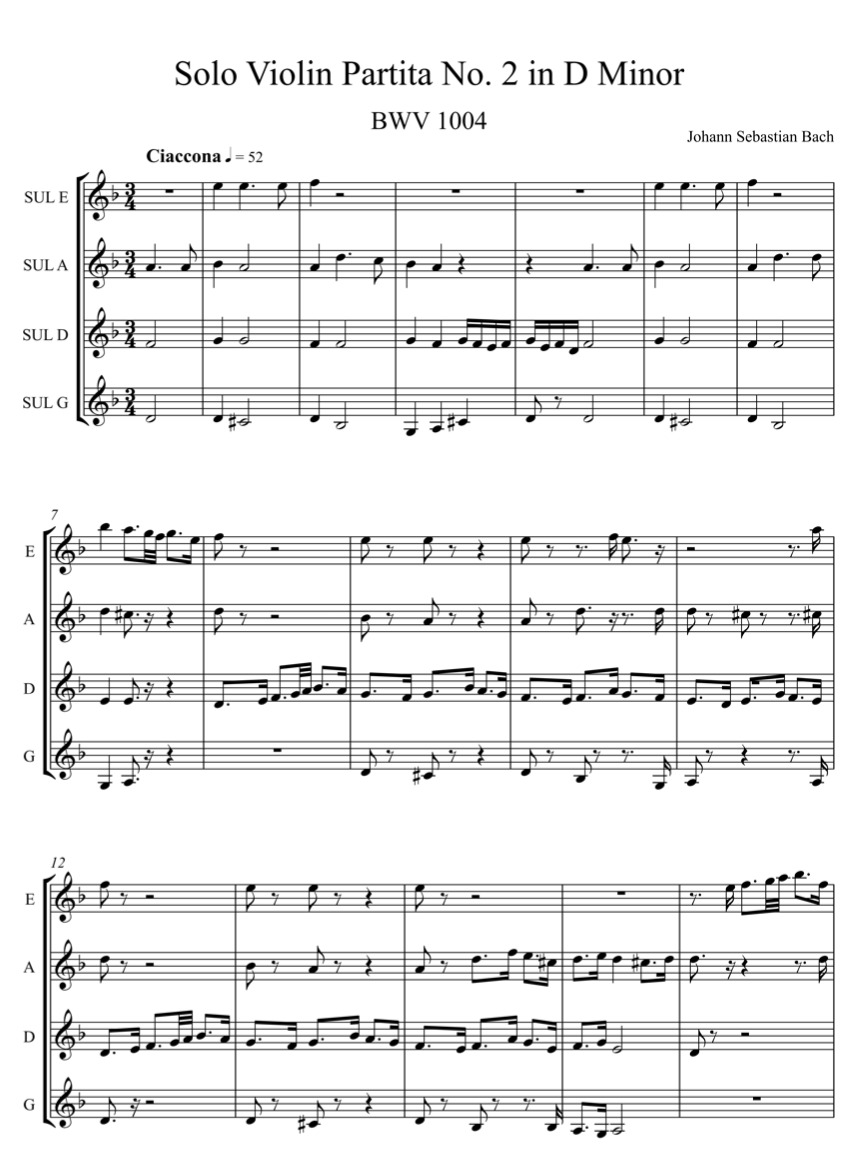

• Analyze the original score based on the practical use of the different strings of the violin.

• Make a new four part score, based on the events and gestures of each string.

• Export the four-part score as separate MIDI files.

• Send the MIDI file data to a modular synthesizer on four separate MIDI channels.

• Patch the channels to four different oscillators, corresponding to and tuned as the violin strings.

• Sample the violin's resonant body, the strings, and various secondary and extraneous sounds, e.g., hits, scratches, and bow hiss.

• Use these secondary sounds as impulse responses to create a virtual resonant body and as sources of modulation for the modular synthesizer.

• Add a performative layer of live patching to play the piece.

Patch 4: Re-patching Bach

Acknowledging the social, cultural, and immaterial aspects of musicking, but also the cybernetic perspectives on musical instruments, this project applies an expanded understanding of pieces and instruments as interactive modular musicking systems. Using this mindset as a conceptual framework, and applied as an analysis of the famous Chaconne from J.S. Bach’s Partita in d minor for solo violin, BWV 1004, a new 'radical interpretation' has been made resulting in a re-composition of the original piece. By deconstructing and modularizing the system that the score, Bach's composition, the instrument, and the performance practice comprise, the aim with this project was to re-patch the agencies of these components of the system, in order to reshape the Chaconne into a new piece, but also to make an interpretation of certain aspects of Bach’s compositional methods. The first performance of the piece took place on March 28, 2023, at the Royal College of Muisc in Stockholm, as part of the Back to the Future symposium.

Background

Conceptually, Re-patching Bach departs from my long-term collaboration with violinist George Kentros in our duo there are no more four seasons. Here, we explore how we could use our experience of new music and contemporary composition techniques to perform old music as if it were written today. It all took off with Vivaldi's The Four Seasons, which was premiered, in the version we created, in December 2004, and after quite extensive touring was recorded and released as an album in 2008. Since then we have made new pieces based on H.I.F. von Biber's Passacaglia for solo violin, Maurice Ravel's Bolero, Johann Strauss II's An der Schönen Blauen Donau, and various other projects.

In the case of the original Chaconne, its agents consist of a famous dead composer, a score, the functional body of a violin, its affordances and ergodynamics, traditions, and performance practices. Thus, the original piece is a complex system that prescribes a certain type of musicking. However, it is also a piece that has been subject to many different transcriptions and arrangements. Besides many transcriptions for guitar, a search on the Internet reveals adaptations for piano (including a romantic version made by Ferrucio Busoni), wind quintet, symphony orchestra (by Leopold Stokowski), electric guitar and drum machine, and others.

A deconstruction enables a new understanding of the original composition, and poses questions regarding what constitutes the object of interpretation. Instead of the standard procedure of regarding the score as 'the piece' and a bearer of truth, the various types of previous musicking connected to the work can also be taken into account. Thus, the many transcriptions and different interpretations and performances of this piece become a crucial part of the piece. How do people play it? Why? On which instruments? What gestures and movements are involved? How does it sound? In the process of deconstruction, the work epistemology is exposed, and this creates a foundation for what you negotiate with while making your own interpretation.

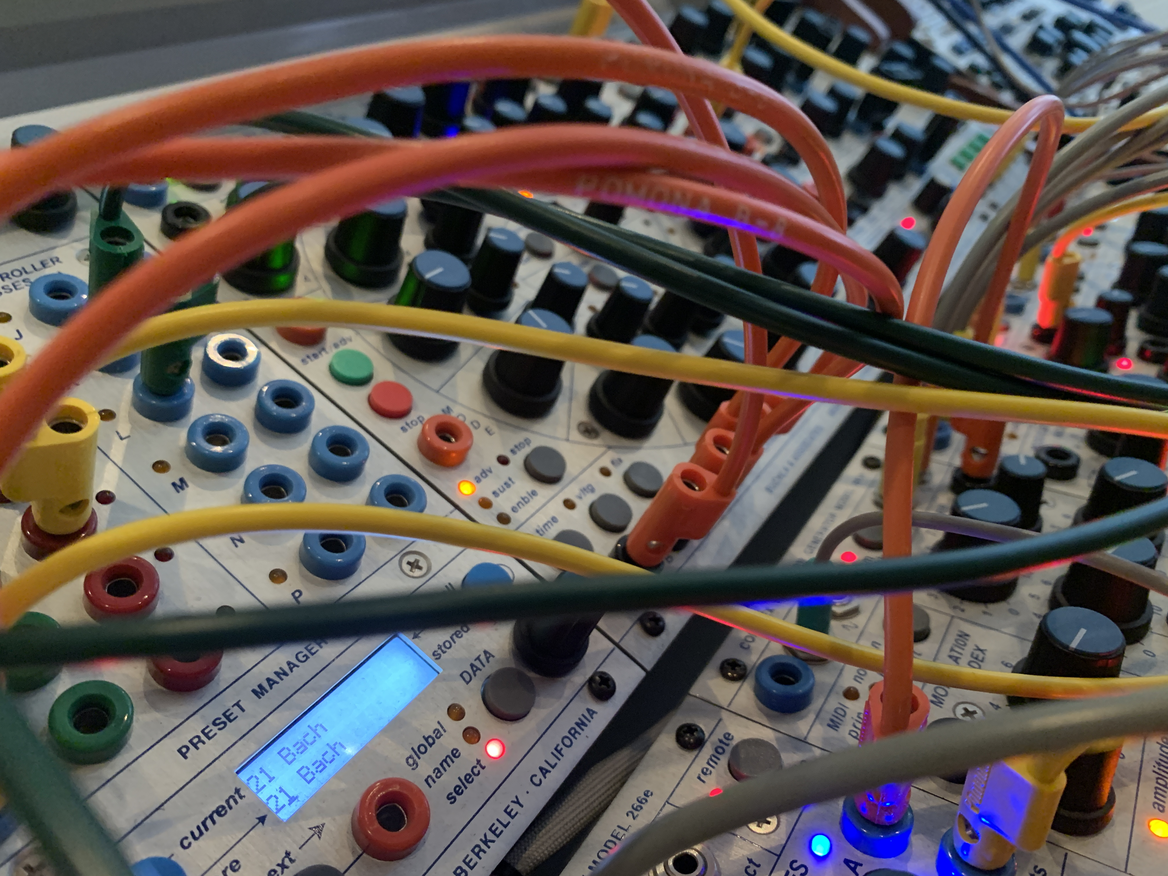

A customized 10-unit Buchla 200e system (shown above) was used to perform the piece. This system was chosen both because of its sonic possibilities and its digital control interface, incorporating an advanced MIDI to CV module, as well as a preset system for settings. The form factor and portability of this system have also made it a regular part of my live setup, usually in combination with Parsimonia, and sometimes also Bitwig.

The Patch

In this piece, the four channels of the 292e were connected to four separate inputs of the audio interface, enabling separate processing. Bitwig's native convolution device was used to add a virtual resonating body to these channels. In trying different samples from the bank of secondary sounds of the violin, I ended up using Bartòk-pizzicatos recorded on each open string as impulse responses (IR). The Buchla 292e channel A was then convolved with the G string pizzicato, the B channel with the D string, the C channel with the A string, and the D channel with the E string. The basic idea was to connect the oscillators representing the E, A, D, and G strings to the 292e channels A, B, C, and D, and thus mirror the resonances. However, it is, of course, possible to patch differently for different performances. Furthermore, the four channels of the 292e were grouped and routed through a global convolution device, using a recorded hit on the body of the violin as IR.

Three more layers were added in the Bitwig setup: First, a basic polyphonic synth plays the original's all four parts, ring-modulated by the Buchla 292e return. Second, the four parts play discrete Sampler devices, using the Bartòk pizz samples mapped in a mirrored fashion, such that the e string part plays the g string sample, the a string plays the d string, the d string plays the a string, and the g string plays the sample of the e string. The third layer consists of eight percussion tracks with a kick drum sample each. The rhythms are derived from both the original and retrograde versions of the parts, although hits are triggered with a very low probability of only nine percent. All these three layers are convolved by the same violin body hit as mentioned above.

For the first part of analyzing the score, I consulted the violinist George Kentros, who marked the score with different colors, according to the string on which the notes are played.

The recording above is from the lecture recital that was part of the Back to the Future symposium at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm, on March 28-29, 2023.