Theoretical premise: “Coming back to the body”, interiority…exteriority

I walk down the street with a friend, she talks about her plans to spend some time dancing abroad over the summer and utters: “I want to start getting back into my body.” Where has she been until now? The saying is very familiar, many times heard and also uttered by myself. I start to think of my colleague Nele in one of our sessions, when she said: “Ma olen endast väljas”, which refers to being upset but in direct translation from Estonian reads “I am out of myself” ("I am besides myself"). Then there is the infamous “listening to your body” – from where exactly are we listening to ourselves? Such seemingly obvious and everyday instances lead me to ponder the body as a place – likewise, a room – we inhabit.. experience.. live…leave… relate with and from, wonder away from…and can return to. One could read such sayings as a separation in which the body and self have become divided, or one could also read it as a relationship held in practice between parts of oneself – a self to self relationship.

However, people's need and joy in re-connecting with their embodied aspects of self is something I have witnessed in somatic practice on many occasions.

A human can be in many ways: their attention and awareness gathered into the dense place of the body in a certain location, as well as with their awareness dispersed in global space and their physical selves transitioning between thinned-out places. Philosopher Edward S. Casey analyses alongside geographer Robert D. Sack’s writings that as part of the ongoing “glocalization”, whereby locality is indifferently linked to every other place in the world, that places become exceedingly more thinned and merge with space (2001: 406). Casey posits that thinned-out places put the self to a test, “tempting it to mimic their tenuous character by becoming itself an indecisive entity incapable of the kind of resolute action that is required in a determinately structured place like a workshop.” (Ibid.: 408) He holds that the more places are thinned out, the more people will need to find “thick places” – as given in the Aristotelian model of place – for their “enrichment”. Could it be that when my friend and many others claim wanting to “come back to their body”, they are reflecting the desire to return from a spread out existence in space to a thicker place of their own?

It seems to me based on experience that whereas our mind’s attention and consciousness can reach across space, the body – even though evolved through time and across ecosystems, developed though consuming both locally and globally sourced food and culture – resists a full thinning out. The body persists in its locality, even when we move and accelerate through space, its thickness stays with us, and it yearns to be attended and expressed.

In “Kohtkeha”, one of the aims is to form a more grounded relationship with the thick and pulsating materiality of the body, which involves a shifting of attention from the surrounding space and activities towards the interiority. Living and experiencing as a body, writes philosopher Hans Rainer Sepp, can become exceedingly grounded to what lies “external” to the body, with both our awareness and experience disguising themselves “with the escape into the objects” (Sepp 2023: 36). A similar line of thought can be also found in Erin Manning’s proposition of “a leaky sense of self”, whereby the body-world is always tending to and attending to the world (2013: 2). She writes: “Being and worlding depend on the activity of reaching-toward. Reaching-toward foregrounds the relationality inherent in experience, a kind of feeling-with the world.” (Ibid.) My wish here is not to contend the relational ontology of the body (and world), but rather to question and highlight the possibility and potentiality of reaching within. What about having a direct experience of oneself? What does tending to and attending to the inner ecology of the body do? How do we understand interiority in experience, existing simultaneously as a transcorporeal eco-subject?

Underneath the experience of the world, there lies the interior experience of self, difficult to grasp but nevertheless part of every experience of the “outside”. Sepp describes it succinctly: “The peculiarity of this interior consists, consequently, in the fact that it is reflexively not capturable: it stands in no correlation to any experience that gives it originally,” and as a result “usually does not become thematic” (2023: 37). He calls it the “primal interior”, which is the ground for our experiencing itself (Ibid.).

What is necessary for having an experience? Experience of the aspects of yourself which might be more in the unconscious, more subtle and tender in their presence, lying under and above the tonality of everyday embodiment, humaning?

It might be that the first requirement is space and time. '

Unless you are after experiences that puncture you with strength and speed. Such experiences simply grab hold of your bodily space and time.

There are many ways to have experiences, many ways to be in experience.

What is your habitual experiential modality of being? Which experiential consciousness do you embody and act from most often? Would you like your experience of yourself, others and the world to diversify?

Well, then make/take/allow/open up space and give it time — give it an opportunity, and opening, to come forth.

It is a room where four people gather to be a body. Unconditionally, without knowing what the practice of being a body entails in its ever evolving entirety. They enter to land within themselves (where were they before?), to perceive their inner spaces. They find themselves in a pressure-free environment where the body, with a tendency to become excessively condensed and accelerated, can find the organicity of its flow. To body is to be in experience. Here, they are guided by the dynamic process, desires and needs of their living matter, and their individual embodiments act as evolving and changing scores of the now. To body is to create and hold space. Experiencing creates a field that fills the seemingly empty room with a felt enmindedness, which can be entered into and joined with.

You are invited within.

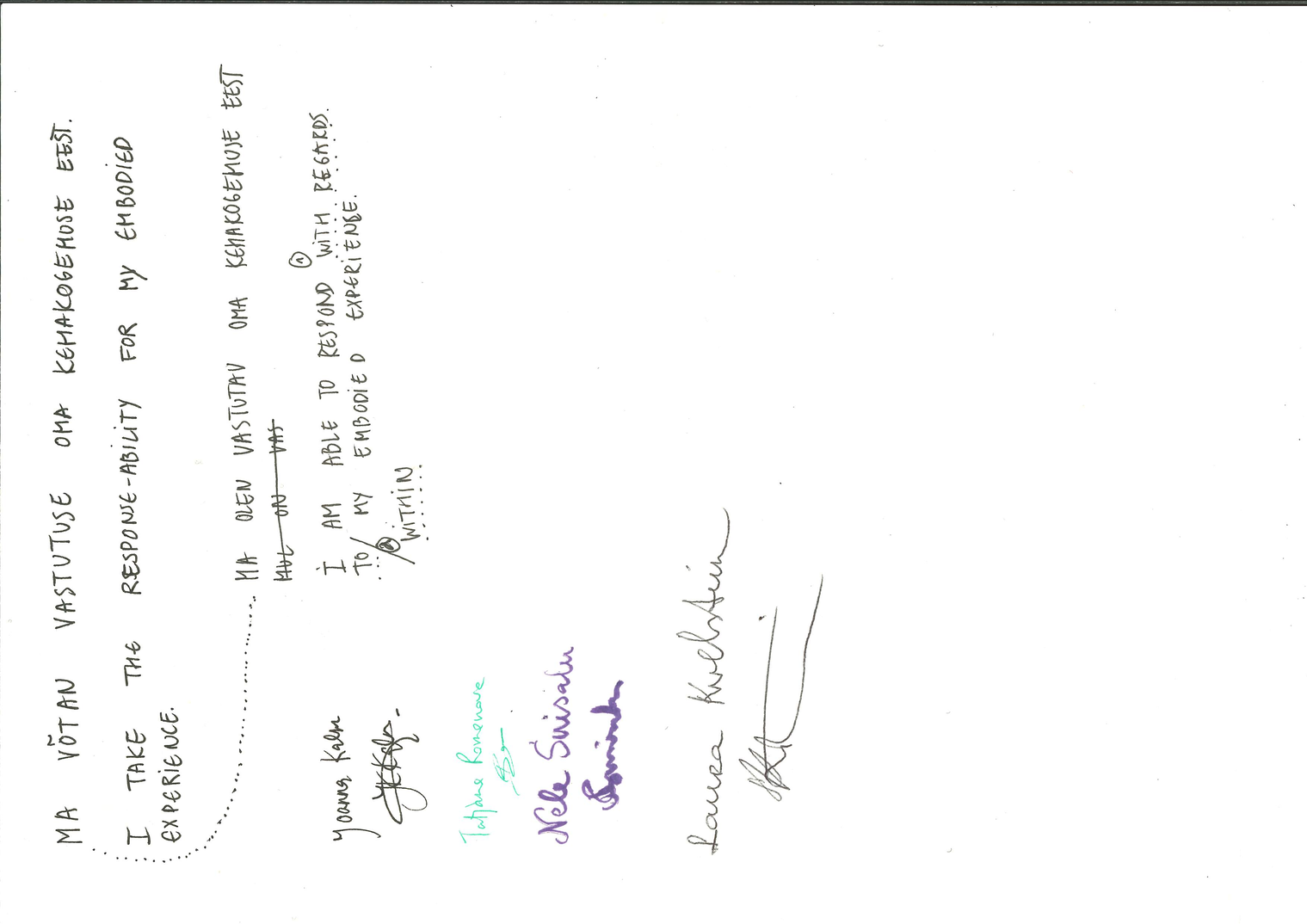

The space is held by dance artists Joanna Kalm, Laura Kvelstein, Nele Suisalu and Tatjana Romanova. They met from fall of 2022 until September 2024, sporadically and periodically intensively. Bodyplace is a somatic practice and/or a durational performance and/or a generator of embodied reflexivity and conversation, which emerged out of a collective studio-based meetings – of deep hanging out with our bodies and each other.

Every room / space / body has an ethiquette which reflects its/their ethics and is communicated through various means that are embodied, enacted and materialised.

In Bodyplace, the room speaks and signals with soft surfaces.

With carpets and pillows.

With blankets.

With a quiet atmosphere.

With daylight.

With tea and coffee and snacks.

With a vacuum cleaner in the corner.

With drawing utensils and papers on the floor.

With books.

With notes and drawings on the wall.

The room speaks and signals with undulating bodies.

With resting bodies across different surfaces.

With soft and listening steps.

With a caring presence that does not rupture others' presences.

With diverse dances of becoming.

With no pressure to perform according to existing standards.

With attentions turned inside.

With talk about minute and passing sensations.

With asking: "How are you?"

Embodied ethics of the practice and room:

-

Care and comfort: the material setting of the room invite to position oneself in a place and position that feel comfortable for them; seeing the performers being comfortable and taking care of themselves gives permission to the visitors to do the same;

-

Somatic agency: every body can follow their of embodiment process as the basis for action; personal somatic sensations were treated as valid and crucial for decision making;

-

Sustainability: being, expressing and engaging was in accordance to present personal resource; no to extractivist tendencies; supporting well-being;

-

Diversity and inclusivity: performers allowing themselves to materialise differently, to fall out of normative embodiment, thus encouraging visitors as well to experiment and widen their embodied expression-engagement; supporting ethodiversity; being aware and honouring one’s own and others’ diverse wishes, needs and boundaries.

To be honest, we do not say too much when you enter. Bodyplace is a spherical space: you enter, you are already in it, with your questions and doubts.

We see you, acknowledge your entrance and presence with our bodies; usually, but not always, one of us would afford a verbal 'hello' or locking of eyes, to confirm your arrival.

We offer you a papersheet with guiding bodily pathways upon entrance. The papers are at the door. We hope this makes your landing easier, but there is also a chance you passed it by.

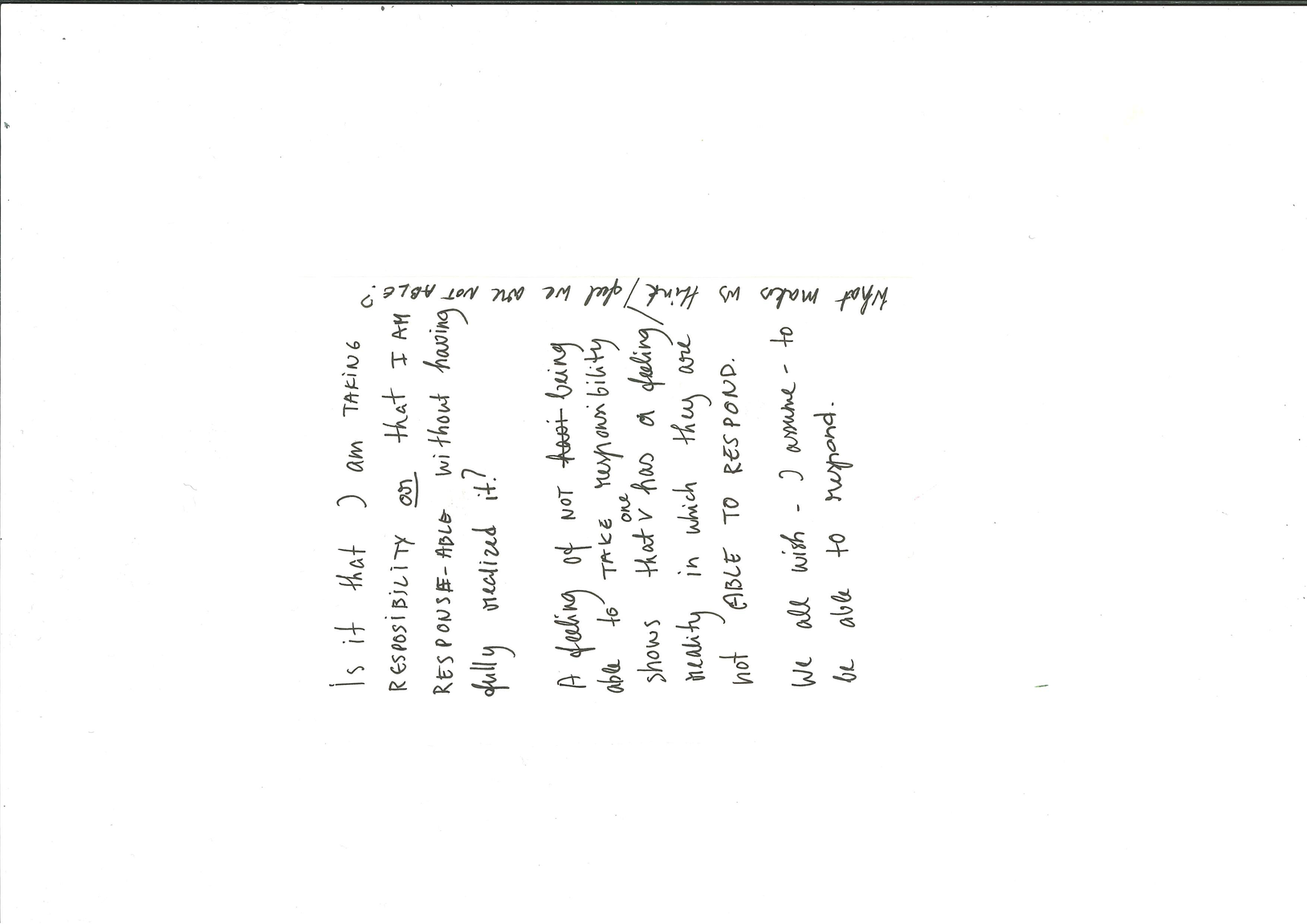

That's okay: this room is about figuring out how we are bodying and in that sense it is a lot about personal responsibility and accountability. We are not here to tell you how to be a body, how to human. Rather, it is a space for allowing our priorly composed embodiments to unravel and re-configure. We are in processes of undoing and becoming. Observing and questioning our own enminded materialisations.

A visitor expresses: “It is so good to be here that I am aware of not wanting to break myself or the surroundings.”

I ask intuitively: “You mean that you develop a sensitivity towards yourself and the surroundings?”

She responds: “Exactly. It is like being in a bubble and I do not want to break it. When you enter the room, there is a whole other feeling here compared to the outside.”

2.3 Affective embodied subjectivity

The performers' embodiment process acts in the room as a practice-based example of how visiting bodies could engage with themselves and the room. Hereby, the directing of the situation is done through implicit exemplifying, not telling visitors how they ought to be-move-engage. This highlights visitors' personal agency as well as foregrounds the affective capacity of embodied subjectivity (as a mode of education).

2.4 Embodied reflexivity and conversation

The practice entails embodied reflexivity and conversation as a method, which opens up personal and shared processes through a cognitive and verbal layer. The aim is to make the often ephemeral and preverbal embodied sensemaking more tangible as well as accessible for visitors. This allows the visiting bodies to enter and join the practice and affords a way performers and visitors can engage in verbal exchange.

2.1 Space holding (co-regulation)

2.2 Somatic self-regulation

2.3 Methodology circle

2.3 Affective embodied subjectivity

2.4 Embodied reflexivity and conversation

2.1 Space holding (co-regulation)

The whole process of Bodyplace and its practice is underlied by the notion of "holding space" (Keleman et al. 2017; Kessler 2012; Floyd 2016). Holding space is a widely used term and approach in therapy, psychology and also palliative and supportive care, which refers to an attentive and empathetic presence with others in a situation, as opposed to actively “fixing”, “curing” and “doing” in care settings (Keleman et al. 2017). It involves intentionally cultivating a safe space for active listening and for allowing others to initiate action.

For me, as a project lead, it emerged intuitively, mostly from a place of not fully knowing how to start unravelling the questions surrounding somatic self-materialisation. I sensed a connection (based on the work I had done during my MA studies) between somatic self-listening, self-regulation and autopoiesis, the ability of an organism/system to maintain its homeostasis and reproduce itself within its operative organisational closure (refer to part 3). In short, I wanted to afford space and time so as to observe how my collaborators and I would regulate-organise-materialise based on somatic listening, which, I feel today, meant listening to the autopietic unravelling of the body-subject.

At the same time, I was increasingly aware of the power a practice has over people's embodiment. To hold space means to hold bodies. So, how to hold this space? What kind of practice do I propose? The practice acts, in the words of Barad, like an “apparatus”, a material-discursive reconfiguring that comes to produce certain phenomena. The phenomenon is what unfolds, a dynamic relationality taking place through intra-actions (Barad 2003: 820) – ways of embodying the self. Given this premise, I remained cautious of what kind of framing and signals I was providing for the group.

In many ways, I was in a praradoxical situation: wanting to witness differential becomings, but not able to say how it could be attained or direct it very overtly. Because to do that, would have meant to define the practice and the findings, but I wanted us to figure out a collaborative and intra-active becoming of both – the practice framework and our embodiments. Not to allocate most of the power to the side of practice to form certain kinds of bodies, but to allow embodiment processes likewise to shape the practice. Ultimately, I was aiming for having both sides – embodiment and practice – responsive.

So, I became a space holder.

A position, which is also reflected upon by Corrigan in Open Space Technology, a group facilitation approach (2006: 9):

This is the pure practice of servant leadership. You have nothing to offer in terms of direction, only a container to hold and a will to manifest. You place yourself outside the circle, get out of the way when the marketplace opens and you find that the group manages itself.

I pose that holding space is an act of extension, of becoming a room for another person(s) and their process to express into. This is what I knew how to do, intuitively: remain present, listen, perceive, respond. Like a therapist, I would say and do in response to what was released into our shared space. I/we and the room support emergence.

However, what we started to notice during the development of the practice is that the way I/we collectively held space was not by being the “frame” for the situation. I/ we were not situated on the “boundary” of the practice, in support of what was unravelling within the group. Rather, I/ we were in the midst of the practice – being part of our own evolving embodiments and holding space for one another at the same time. Therefore, it became evident that the participants, maintaining a receptive and empathetic openness towards their own and others’ embodied processes, were also active as “space holders”. In fact, being in the process of somatic self-listening and -expression seemed to be an act that creates, holds and informs space.

Holding space is an invisible action, yet actively felt – may it exist as a field? How does self-experiencing create, hold and inform space around and thereby affect others' embodiments? These questions invite us to acknowledge the affective role of embodiment, not just for the self but to the collective, whereby personal embodiment can impact how others' perceive and form themselves. This is where somatic embodiment gets socio-political.

People fret that structure leads to action. That is true, but it is not the structure from outside that leads to actions, it is the structure that emerges from the inside that is where the explosion of action originates. Like a seed that contains the tree.

(Corrigan 2006: 51)

2.2 Somatic self-regulation

The underlying method for the practice/room is to follow one's own embodiment process as an evolving score in the now, thereby highlighting how felt needs, desires and boundaries are in a constant shift anf inform our actions. Furthermore, the dynamics of each person – both the working group members' and visiting bodies' – becomes the basis for content emergence and dramaturgy (spacetimemattering) in the moment. Additionally, the performers and the visiting bodies are encouraged to inquire into the dynamics of their living matter and be-move-engage in as much harmony with their personal processes as possible. In short, we practice being somatically agentic. The ongoing research inquiry looks into how participants' expression – experience in time, intensity, scale, movement modality – and engagement – inwards... outwards attention and action – can start to re-form differently when parts of somatic self are fully included and expressed.

The set-up affords observing the embodied subject in space, however there is a methodological gravitation towards self-experiencing and feeling with others. The practice relies heavily on inereoception, persons' ability to perceive sensations from their tissue matrix that inform them about energy, emotions, temperature, motor initiation, pain, needs etc. As the internal dimensions are highlighted and become affectively present in personal body and surrounding space, visual perception is no longer as prominent, compared to more traditional dance practices and performances.

The practice evokes a "turning around" of perspectives, as worded by Annika, a visitor, whereby the person undergoes an internal (and spatial) turn in which they go from looking at the practice from the outside to turning their attention towards their inner space and therefore looking outwards from themself. This turning faciliatets witnessing the practice as performance unravelling within, which means the visiting body themself becomes a place of performance. Looking at the practice is possible in as much as one takes part in it.

Somatic self-regulation – Presencing and bodying in relation to personal embodied process/ing.

The latter includes:

practical and creative actions taken for maintaining organismic allostatic and homeostatic baselines;

attuning to needs, desires, boundaries as perceived via interoceptive, proprioceptive, exteroceptive and vestibular sensory-motor processing,

and responding to sensations and perceptions with practical-creative presencing and bodying;

sensory-motor looping as a way to thinkfeel in movement and process information and emotions.

Entering a room,

circling inwards,

turning around,

the gaze turns towards self,

I becomes the place of gaze,

a feeling-ground of

self,

the room and others

BODY IS THE SCORE

BODY KEEPS THE SCORE

BODY REWRITES THE SCORE

SPACE IS THE SCORE

SPACE KEEPS THE SCORE

SPACE REWRITES THE SCORE

The room, we came to realise through practice, acted like a cellular membrane. It contained us without separating us.

The gallery space has big windows, which allowed there to be information flow (light, sound, people looking, entering, exiting) between the room and surrounding environment.

As a result, the room could maintain its own integrity, similarly to cells in the body, which are in intra-active relations with the environment, but which nevertheless decide and modulate what and how much passes into and out of the cellular-body space.

It is acknowledged in cellular biology that it is the emergence of the cellular membrane that makes the formation of an organism possible, as it provides structural integrity and a underlies unification. Without the membrane, the cellular strata – and we – would be lost to the spatial dynamics and differentiation between bodies would become impossible.

Thus, being a membranous being and inhabiting membranous spaces entails simultaneously two modus of existing: experiencing relative containement and existing in relations.

Cellular sensemaking (CS) is one aspect of the somatic sensibility in development in my doctoral work. Cellular sensemaking invites to consider organismic organisation and regulation on a basal level and in relation to expanded and human-scale engagements. Furthermore, CS invites to feel into the small stuff, track our sensations on a small scale that goes often unnoticed, and realise the agentic capacities of the cellular matrix.

Throughout our process, we kept on returning to thinkingfeeling with the cellular membrane. This started from one of our somatic practices during which we worked on the fluid-membrane balance of the cells (class material part of the Body-Mind Centering Fluid System Course). We sensed into the tone of our skin membrane and of other tissues present in our bodies, focused on the simultaneous condensing and expanding yielf taking place in the body, and felt into the fluid movement around the cells and through the membrane, as well as the calm the presence of fluids in the cells.

Thinkingfeeling with the cells become a practice of attunement to the micro-sensations, not just on a tissue or organ level, but beyond and inbetween. We could track our im/permeability, tensions and relaxation, openness and closeness, fluidity and stuckness by attuning to our cells.

Additionally, it allowed us to attend to questions regarding interiority and exteriority, both on a cognitive level and through experience. I needed to understand better what does it mean to work somatically – following personal sensations – as an ecologically formed subject existing in myriad of relations with matterings others? How can a somatic sensibilty, which entails a certain organismic boundedess, co-exist with practices and philosophies of transcorporeality and agential realism – posthumanist frameworks?

Tone can be considered as a felt sense of liveliness present in all the tissues of the body, including “the mind” – a certain readiness and capacity to perceive, engage and act. Chiropractic Donald McDowall et al. posit in a health science literature review on “tone as a health concept” that the latter can be described as “the passive neurological condition of strength found in all body tissues” (2017: 17).

There is something about the tensive quality of tissues. The body is not slacking, falling apart, there are internal relations between cells and tissues, which manifest itself as strength, but also as weakness and as tension.

Tone, according to the teachings of somatic movement approach Body-Mind Centering™, is based on vibration (Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, 2025). Each tissue, emotional state, environment or situation vibrates in their own tone. Vibration makes me think of movement: the minute shifting back and forth, from side to side, in all directions of the space. Tissues… cells… molecules… of the body but also of matter around us vibrate – they motion on a micro scale even when seemingly still.

Social scientists James Ash and Lesley A. Gallacher likewise posit that “vibration is a form of movement that is common to all bodies and objects (2015: 76)”. It feels to me that the movement – vibrational – capacity and quality of the tissues is perceived as tone.