Introduction

How can refugia and multispecies practices function as vital modes of inquiry in the context of ecological and epistemic crises driven by anthropocentric worldviews? Artistic research, in this context, offers a valuable entry point into pressing ecological and epistemological debates, contributing to both academic and wider public debates addressing anthropocentric challenges. These debates often center on variations of the same question: How can humankind “save” the Earth so that humanity can survive, preferably in ways that maintain its fundamentally unsustainable modes of living?

At the same time, various intellectual and activist movements have been actively opposing these dominant paradigms – advocating for more just and more sustainable ways of living. Frameworks such as degrowth, decolonialism, post-capitalism, or post-anthropocentrism amongst others form part of a broader effort to move beyond the constraints of growth, colonialism, capitalist accumulation, and human exceptionalism. In contrast to the prevailing question – How can humankind “save” the Earth so that humanity can survive, preferably in ways that maintain its fundamentally unsustainable modes of living? – these movements pose a more generative inquiry: How can we compose more liveable cosmopolitics? That is, how can we live well – with and among each other, including other species?

It is within this broader landscape that I turn to the concept of the more-than-human. The term more-than-human was first coined by philosopher and ecologist David Abram in The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (1996) to describe this richly entangled world – in the sense that humans can only be human “in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human” (Abram, 1996,p.9).

In subsequent years, more-than-human frameworks gained traction, also in artistic research – through scholars such as Donna Haraway, Anna Tsing, Tim Ingold, and Ron Wakkary – who helped shape its relevance across academic and practice-based disciplines. Wakkary suggests in Things We Could Design: For More Than Human-Centered Worlds (2021) that human-centered design contributes to the anthropocentric problem by placing humans at the center of thought and action. The meaning of more-than-human has expanded comparing its original framing by Abram, who used it to refer to an entangled living world:

[a] larger community [that] includes, along with the humans, the multiple nonhuman entities that constitute the local landscape, from the diverse plants and the myriad animals – birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, insects – that inhabit or migrate through the region, to the particular winds and weather patterns that inform the local geography, as well as the various landforms – forests, rivers, caves, mountains – that lend their specific character to the surrounding earth (Abram, 1996, p.14).

Later, Wakkary, includes technological and artificial elements. This is a particularly interesting evolution, given that Abram described the phonetic alphabet as a “strange and potent technology” (Abram, 1996, p.64) that distanced humans from the more-than-human world. He argues that nature began to lose its voice with the spread of the alphabet. Unlike pictographs and ideograms – whose shapes directly referenced to natural forms like a paw prints, the sun, a serpent, etc. – the alphabet locked language into a purely human system.

More-than-human frameworks are lacking a shared conceptual grounding, which has led it to be interpreted and mobilized in markedly different ways. When Abram (1996) coined the term, he used it adjectivally – e.g. more-than-human world, field, realm, ecology, matrix, cosmos, earth, terrain. This way, it refers to [a] an expanded collective that includes humans and nonhumans, offering a (set of) lens(es) through which we can perceive and understand the world. However, more-than-human has also been employed to describe [b] a distinction between the human and the more-than-human, thereby reinstating the very separation that the term was originally intended to disrupt. The conceptual power of the former becomes diminished in the latter usage; reduced from a rich lens of multitudes to a mere synonym for nonhuman, a rebranding of nature of you will (Just, 2022). Using more-than-human as an adjective rather than a noun matters because it keeps the concept alive as a relational orientation, as it becomes grammatically embedded within a process, a field of action, or a way of knowing, instead of turning it into a static category.

For example, during an interview with Steve Paulson for Los Angeles Review of Books (2019) Donna Haraway answers to one of the questions about kinship: “If I am kin with the human and more-than-human beings of the Monterey Bay area, then I have accountabilities and obligations and pleasures that are different than if I cared about another place.” While Haraway stresses a kind of situated care and attachment, referring to human and more-than-human beings in this way, risks setting them in opposition, defining the latter only in contrast to the human rather than in relation with it.

While intended to de-center the human, the term more-than-human itself re-centers the human by using it as the point of reference. By doing so, not only does it tend to reinforce the very human/nature binary it seeks to disrupt, but it could also unintentionally risk reaffirming the very focal point it seeks to decentralise. Because, if the human remains the implicit norm – even in this attempt to make more room for all life that allows us to (have) be(come) humans in the first place; would that not potentially put a constraint on the capacity for imagination beyond this point of reference? The unintended focus on the human could be paralysing for those that attempt to create conceptual and speculative spaces that inspire different possibilities (Westerlaken, 2021).

The grapple for what collective nouns to use to define a strong has been challenging. As we reach for concepts and frameworks, each term seems to falter one way or another, holding unwanted hierarchies or contradictions; ultimately incapable to fully hold the depth of what is meant. Humanimal (Mitchell, 2003, xiii) has been proposed as a hybrid word that puts human and animal together. It is a linguistic way of paying attention to how humans and nonhumans co-create each other cybernetically. Its uptake in academic discourse has been limited, and its conceptual utility remains questionable. Similar to the nominal use of more-than-human, the noun form of humanimal risks collapsing the dynamic and relational complexity of interspecies entanglements into a static categorical identity. Moreover, the term fails to account for nonhuman, nonanimal life forms – such as plants, fungi, and microorganisms – narrowing its conceptual scope.

Another term, multispecies (Haraway, 2003, 2008) has also been contested. Timothy Ingold argues that it is only from an anthropocentric sovereign perspective that nature can become a classification of various species (Ingold, 2013). Abandoning this perspective, Ingold reasons, challenges the very concept of species, as it requires rethinking how we group beings based on similarity and difference.

In short, the struggle to conceptualize this fully – to find language expansive enough to carry it – remains an unsettled quest. However, despite their limitations, these terms should not be discarded; rather, as Haraway (2008) encourages, we must “stay with the trouble.” Even as these terms may evolve into better frameworks, they serve a crucial function now to ally human and nonhuman worldings together against binaries. In the search for a shared conceptual framework, these various terms converge – albeit imperfectly – on the idea of reciprocal accountability – of learning to see and to respond to one another.

For many Indigenous cultures, such ways of relating are not abstract concepts to be defined. Instead, they are lived realities, embedded in the land, stories, and practice. However, while acknowledging the richness of multispecies cosmologies, uncritical adoption of Indigenous knowledge risks constituting a form of neo-colonial appropriation, which Zoe Todd (2019) terms “white public space”. Todd (2019) emphasizes the need to develop our own approaches to multispecies thinking that remain attentive to the context and relationality. “[A] superficial engagement with indigenous thought is already made possible by the still-influential inheritance of colonial ways of understanding indigeneity, and the omnipresence of rights discourses in modernity helps to further assimilate indigenous philosophies to Western ones” (Tanasescu, 2022, p.42)

This underscores the imperative for non-Indigenous practitioners to cultivate their own modes of worlding – not through replication or superficial (and often romanticized) adoption of Indigenous concepts, but through embodied, relational engagement that allows multispecies relationships to unfold organically. Rather than relying solely on theoretical frameworks, this approach prioritizes doing – embodied engagement – messy exploratory practices based on being together.

In this way artistic practices can be developed and tested within diverse environments as speculative tools for multispecies communication beyond mere verbal communication which represents human ways of understanding. Speculation in this context is a practice of bringing to the surface alternative worlds that are already real and present. This interpretation of speculation is much related to the pluriverse, “a world where many worlds fit, as the Zapatista put it with stunning clarity” (Escobar, 2018, xvi). Pluriversal thinking, is not about inventing what does not yet exist, but about recognizing, affirming, and making space for these coexisting realities. In other words, these worlds do already exist, but are often obscured or marginalized by dominant ways of knowing.

Speculation, then, is not about imagining what is absent, but about revealing and sustaining alternative worlds. These worlds are already present, even if they are rendered invisible or marginalized within prevailing epistemologies. Speculation in this context becomes a practice decolonization and deanthropocentrizing of knowledge by dismantling dominant knowledge structures and making space (spacemaking) for alternative modes of knowing and being.

Refugia spacemaking

As I walk through a nature reserve at dusk, the light fades slowly. I hear jackdaws chirping as they settle into the trees for the night. A mosquito lands on my hand. I feel its tickle and slap it away. That sudden sound startles a nearby rabbit, which scurries away. The rabbit senses my steps as vibrations through the ground. In turn, I cannot hear its soft paws; it is too quiet for my ears. But an owl nearby catches every hop with ease. Meanwhile, the jackdaws could not care any less about any of this. They just want to rest until morning.

Each being inhabits its own umwelt – a concept coined by biologist Jakob von Uexküll in 1909. The term, derived from the German word for “environment,” refers not to the objective environment in its entirety, but to the specific slice of it that an organism can perceive, interpret, and respond to: its perceptual world. An umwelt is thus the unique sensorium through which a being experiences reality. Humans can never experience the world as a whale or as a plant, because we cannot fully inhabit the perceptual worlds or knowledge systems through which other species engage with reality.

If diverse umwelts serve as an epistemological map for exploring multispecies encounters and collaboration, then the landscape becomes a verb rather than a noun; and humans are part of that landscape (Mitchell, 2003). Landscape is not something out there to be seen, instead it is a process of becoming and responding. Inasmuch as jackdaws, rabbits and owls are part of our landscape, we are part of theirs. Hence “landscape (whether urban or rural, artificial or natural) always greets us as space, as environment, as that within which 'we' find – or lose – ourselves.” (Mitchell, 2003, p.2). In other words, humans are not external observers of the natural world but are themselves embedded within it, positioned as situated beings within complex landscapes (Haraway, 1988). This embeddedness entails that human action is always participatory, entangled in ecological processes, and thus consequential. Human practices – ranging from industrial agriculture and mining to patterns of consumption – actively shape and transform ecological systems.

Human practices may serve narrow anthropocentric interests or attempt to address the needs of the more-than-human world; but either way, these interventions are always entangled within broader ecosystems and their consequences unfold there. These consequences today include mass extinction, deforestation, and many other forms of ecological destruction, pointing to the urgent need for a new era of reciprocity with nature (Fletcher et al, 2024).

Refugia emerge as critical spaces where life can retreat and survive during periods of environmental stress. As refugia become scarcer, destruction not only ends lives but also forecloses the very conditions that enable life renewal. In this sense, death loses its unique regenerative qualities and turns into a double death, where futures collapse into the present (Bird Rose, 2004). It is an erasure of worlds and possibilities that might otherwise have lived on because death becomes profit instead of regenerating into life (McBrien, 2016). In this way, refugia function as spatial resistances offering a counter-narrative to the alienation caused by conceptual dichotomies such as human/nature and life/death.

In this context, I propose to explore refugia as shelter spaces for multispecies continuities, cultivating kinship and meaning-making. Refugia invite the exploration of alternative, ecologically attuned practices through which situated beings can engage with their environments. At the same time these spaces extend beyond their ecological role and act as spaces for stories, ideas, and imagination to persist. In dialogue with the concept of double death, refugia might instead be understood as spaces of double birth: not only do they create context for nonhuman life to survive and flourish, but they also open room for possibilities to emerge. Refugia allow multispecies practices to persist and thrive, even when the surrounding systems are inhospitable to multispecies co-creation. This way, refugia safeguard knowledge sharing and production that might otherwise be marginalized or erased. It creates space for speculative futures, counter-narratives, connection and relationality. This spacemaking process invites stories and experiences, that go beyond the humancentered narratives.

When engaging with humans and nonhumans in site-specific participatory practices, it is essential to acknowledge the existence of these distinct umwelts. The space should allow for these other ways of perceiving to be actively present, meaning that these multispecies encounters should not be intended solely for human understanding. Instead of assuming human superiority and attempting to fully comprehend the nonhuman by fitting it into frameworks designed solely for human understanding, alternative approaches are needed. This way, through practice, these multispecies encounters create spaces, for new ways of knowing, alternative processes and systems of reciprocity and care. “Rather than fantasizing about untouched nature or returning to a pristine past, we must learn to live with, respond to, and care within the ruins – with other species, damaged landscapes, and uncertain futures” (Anna Tsing, 2017). This kind of spacemaking – where different ways of perceiving the world can shelter – is exactly what has been defined as the Terrapolis (Haraway, 2016), the Pluriverse (Escobar, 2018), and the more-than-human world (Abram, 1996).

These site-specific practices culminate into acts of spacemaking; spaces that cultivate multispecies kin- and meaning-making. By foregrounding process and relationality over fixed outcomes or normative modes of interaction, these practices open space for the emergence of lived relationships, collective memory, and a sense of belonging. These practices offer a radical reimagining of identity, potentiality, and alliance—challenging conventional assumptions about who “we” are, what we might become, and with whom we can engage. In doing so, the practices disrupt seemingly neutral concepts of humanity embedded within Western scientific and academic discourses, revealing the limitations of frameworks that take human centrality and universality for granted.

Beelonging: a refugium

Multimedia bee hotel installation

Constructed from reclaimed wood, the beelonging installation welcomes a variety of guests in Ghent University's botanical garden – each guest with their own distinct perceived umwelt. The hotel serves as a space where both long-term residents and brief visitors can interbee. The long-term resident is the wild solitary bee, who nests its future generations in the nesting tubes. The brief visitor is the human, a passer-by, drawn by curiosity, chance, or interest. Yet, the hotel remains open to unexpected guests, such as ants, butterflies and wasps. The hotel functions as an epistemic device, revealing how situated yet species-specific activities illuminate the dynamics of distinct modes of perception, labour, and relational agency. The only explanation provided to human visitors is the following text: “Beelonging is a multimedia bee hotel that facilitates encounters between travellers, long-term residents, and passers-by. Different worlds touch each other in the wood. What do we experience in each other’s presence?”

Noticeably absent are conventional information descriptions, such as statements about the ecological importance of bees or their role in biodiversity. By refraining from translating bee life into human metrics – pollination rates, population counts, or ecosystem services – the installation foregrounds the qualitative, experiential, and relational dimensions of existence. Human visitors are invited to enter a de-anthropocentred framework, in the space/physicality of beelonging, without the safety net of more familiar (‘human-centered’) narratives.

The installation does not merely ask humans to observe bees – it prompts a shared presence, where humans and wild solitary bees occupy the same space, each navigating their own umwelt. In this sense, the installation functions as both a space and inquiry: How can humans cultivate attentiveness to nonhumans in ways that neither reduce them to human frameworks of meaning, nor render them invisible, but instead allow for a shared multispecies space?

Attached to the side of the hotel is a digital screen, displaying a looping animation video of approximately thirty seconds. This animation serves as a portal into the multispecies practice that is about to unfold. It shows a cyclical process, situating the human participant within a more-than-human playground that highlights co-creative practice and emphasizes the interdependent roles of humans, bees, soil, wind, and flowers in shaping a multispecies landscape. In this site-specific practice, humans and bees are engaged in distinct yet resonant activities, together composing a space of more-than-human worlding, a multispecium.

Practice of sending flower seed letters

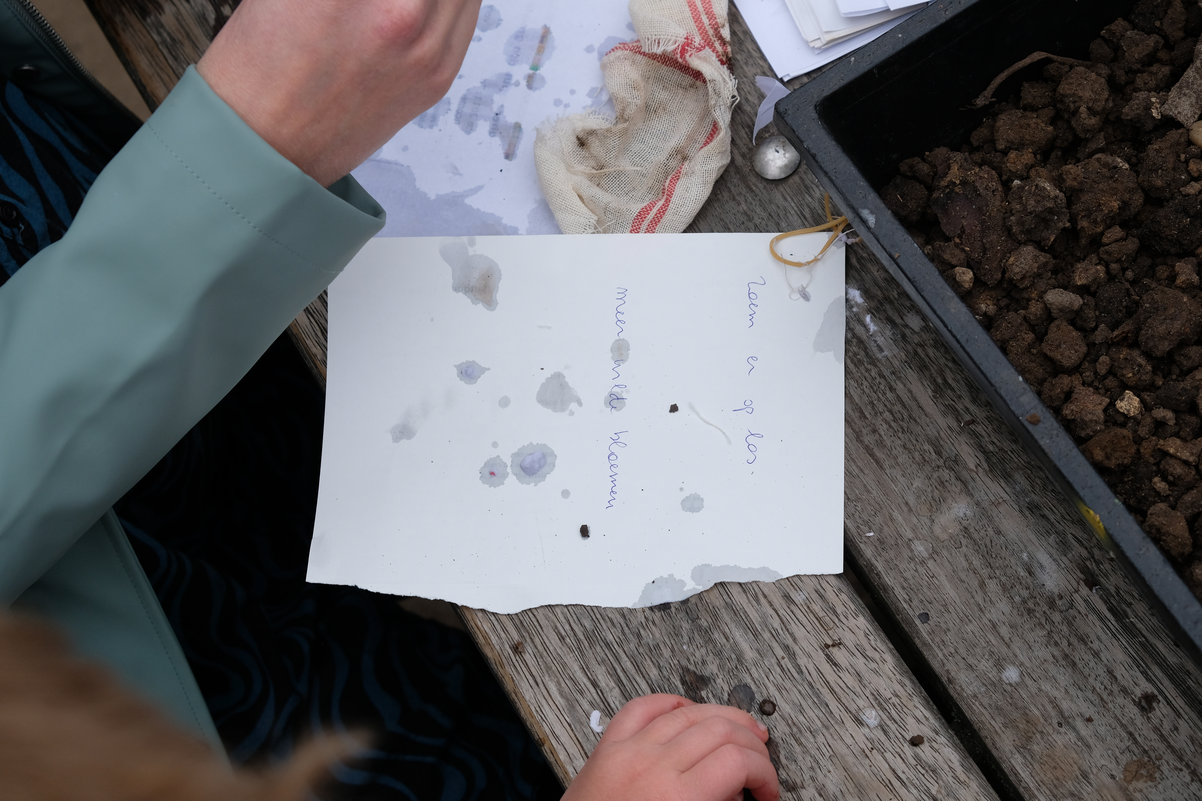

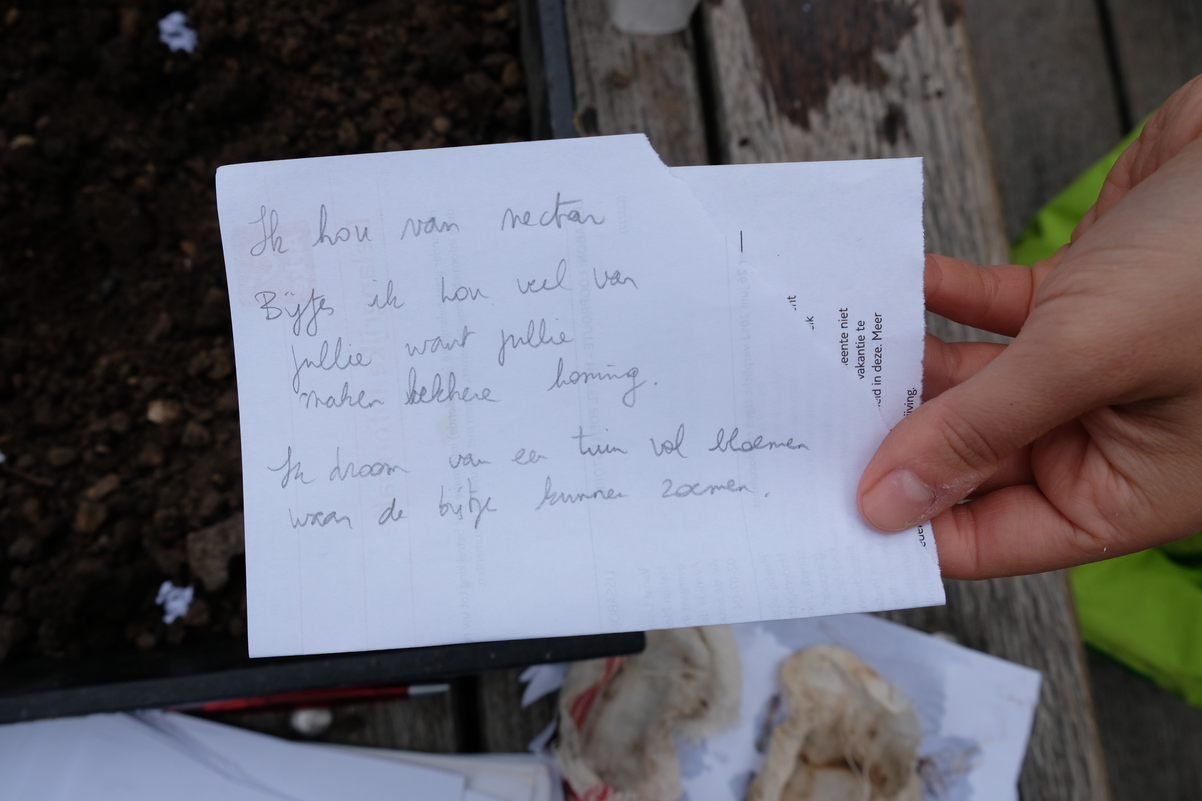

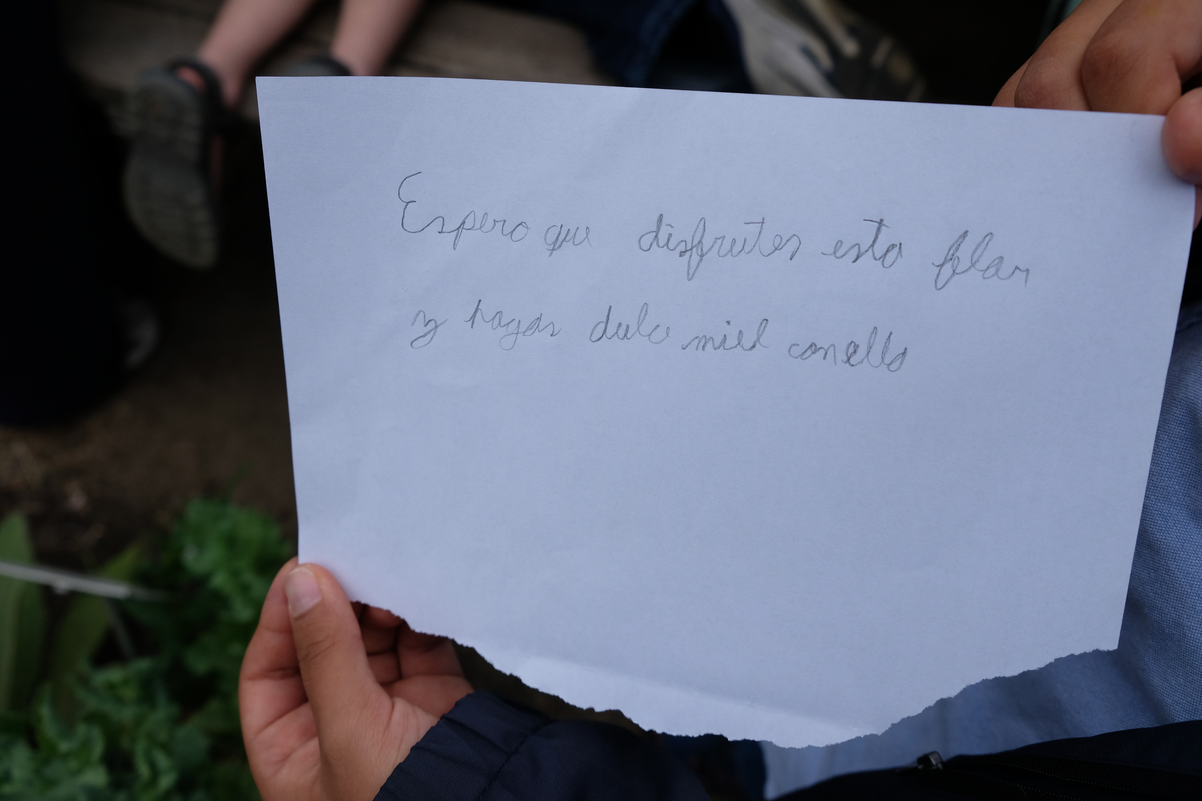

The physical presence of the hotel is amplified through a specific activity that deepens its spacemaking capacity. Human participants were invited to engage with reflective questions about the life of a bee. They were asked: What would you like to say to the bee? and if you were a bee, what would you want to express? Participants wrote their responses on scrap paper – material that would otherwise have gone to waste. This paper, once in the soil, decomposes into organic matter and carbon-rich fibers, improving soil structure, retaining moisture, and supporting microorganisms. These handwritten reflections, or drawings for those who could not write, were then mixed together into paper pulp, from which participants shaped small blobs. Flower seeds – calendula in this case – were placed inside, and another layer of pulp was added to close them off. By squeezing out the excess water, participants formed the mixture into balls. When people plant or even simply throw them onto the earth, they send their thoughts and ideas as messages to nature itself. Their reflections literally take root and grow in the landscape, extending their presence beyond words and becoming part of living ecological spaces.

Engaging materially and ecologically – whether through humans creating seed letters or bees pollinating – generates a space of multispecies interaction and co-creation. Spacemaking in this context is not merely about physical space, but also emotional, social, and ecological space. This extends the bee hotel beyond its physical boundaries, transforming it into a space of reciprocity where action produces the multispecium: a site of encounter, practice, and shared experience across species.

The seeds, soil, human thoughts, bees and paper pulp altogether engage in processes that cannot be fully grasped or experienced directly. A small action, like creating a flower seed bomb and releasing it into nature, initiates ripples that extend through time. In this context, time is not linear but shaped by feedback loops, where actions and interactions continuously influence one another. This interplay produces a form of spatial and temporal agency that transcends individual species and can only exist within a multispecies context. These agencies exist within the in-between space that is neither fully human nor fully nonhuman. The space is shaped by gestures, interactions, care-takings, movements, intentions, thoughts.

Final considerations

The spacemaking process of refugia is not based on a predetermined framework. It emerges from ongoing reflections and actions; from doing, being- and becoming-with. The practice begins with an invitation but unfolds unpredictably as it leaves room for non-control and for more-than-human co-creations along the way.

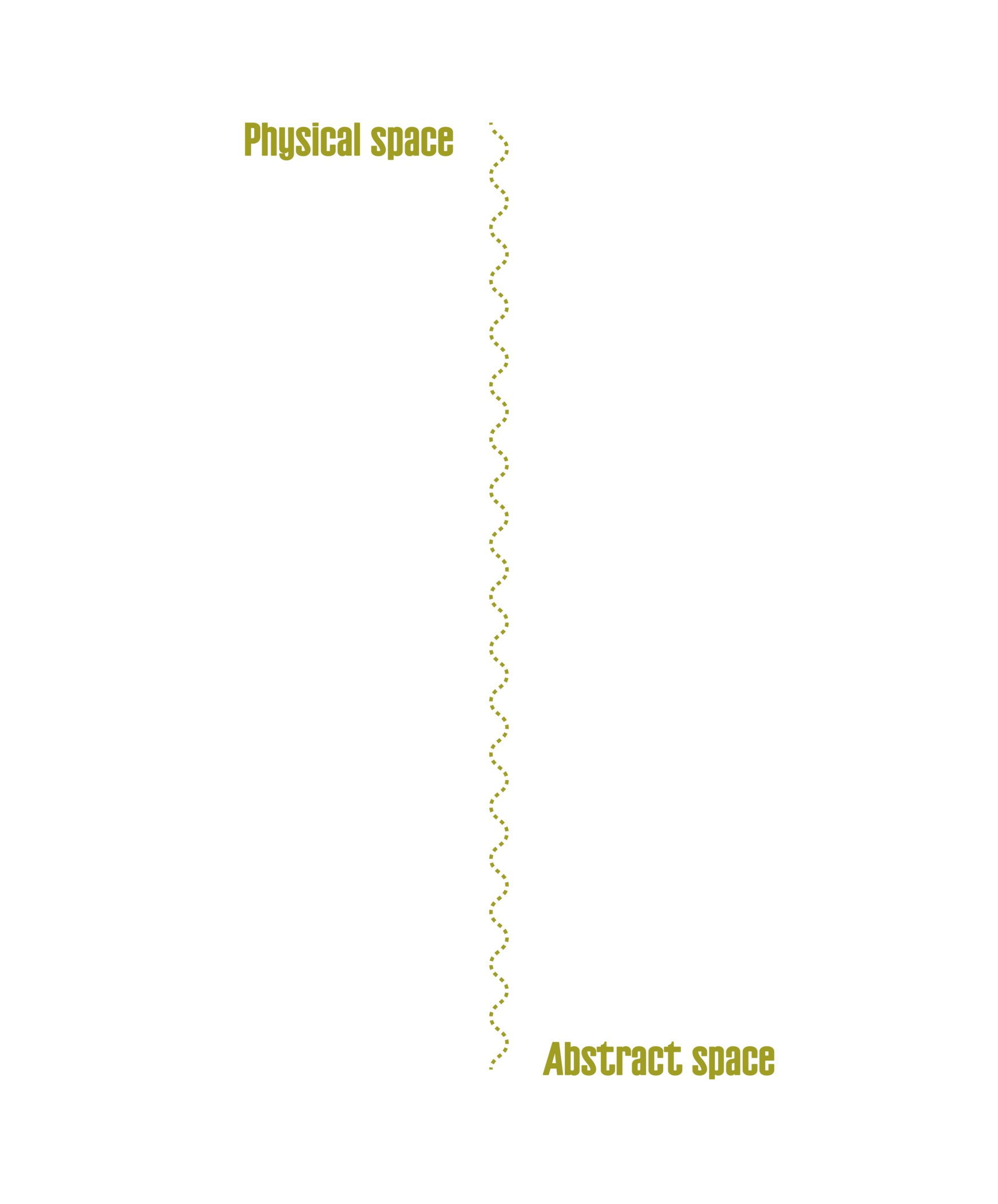

Refugia, as proposed here, exceed ecological and environmental definitions, functions, and roles. They are not confined to a particular locality or physical form but exist also as abstract spaces – sites of relating that are continually made and remade through practice. They are ever becoming, like landscape is a verb. As Beelonging illustrates, a refugium is hybrid in the sense that it combines both the tangible and the abstract. A refugium is rooted in place and in physical systems – like the multimedia bee hotel – while it also extends beyond place through reciprocal acts of attention, care, and speculation – like the practice of making flower seed letters.

Building refugia is a process that is co-shaped by each participant. Participating in the process as such is not merely using the space but means contributing to the building of refugia. Only together can creatures and critters highlight the wideness and plurality of kin- and meaning-making among different species.

At the epistemological level, refugial spacemaking is simultaneously a method and an outcome. The spacemaking process is an engaging practice in which refugia are continually generated, reimagining multispecies coexistence. Refugia unsettle anthropocentric worldviews while gesturing toward speculated futures – that are already present – of more-than-human life. Refugial spacemaking asks ongoing engagement, inviting humans and nonhumans, to co-create living sites.

Refugia, as proposed here, extend beyond their environmental and ecological interpretation, and provide tangible, experiential, and lived encounters. One can enter refugia – anywhere, at any moment – by noticing, by caring, by resonating, by speculating in more-than-human dialogue(s). If multispecies across the world build refugia, they collectively weave a network of refugia: a living system that extends beyond species, geography, and culture. These refugia affirm that no single species or epistemology can monopolize kin- and meaning-making. What emerges is a common that we share: spaces and practices that resonate together.

References

Abram, D. (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a more-than-human World. New York: Vintage Books.

Barnosky, A., Matzke, N., Tomiya, S. et al. (2011). Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature, 471, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09678

Bird Rose, B. (2004). Reports from a wild country: ethics for decolonisation. Sydney: University Of New South Wales Press Ltd.

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fletcher et al. (2024). Earth at risk: An urgent call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(6), e2310210121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2310210121

Haraway, D. J. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Haraway, D. J. (2003). The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people, and significant otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Haraway, D. J. (2008). When species meet. Minneaopolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ingold, T. (2013). Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Abingdon: Routlegde.

Just, J. (2022). Cultivating more-than-human care: Exploring bird watching as a landscaping practice on the example of sand martins and flooded gravel pits. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 11(6), 1205-1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2022.04.007

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2003). Foreword: The rights of things. In C. Wolfe, Animal rites: American culture, the discourse of species, and posthumanist theory (pp. ix–xiv). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Paulson, S. (2019, December 6). Making Kin: An Interview with Donna Haraway. Los Angeles Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/making-kin-an-interview-with-donna-haraway/

Tanasescu, M. (2022). Understanding the Rights of Nature: A Critical Introduction. (New Ecology, 6). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839454312

Todd, Z. (2015). Indigenizing the Anthropocene. In H. Davis & E. Turpin (Eds.), Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters among aesthetics, politics, environments and epistemologies (pp. 241–254). London: Open Humanities Press.

van Dooren, T., Kirksey, E., & Münster, U. (2016). Multispecies Studies: Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness. Environmental Humanities, 8(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527695

Wakkary, R. (2021). Things we could design: for more than human-centered worlds. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Westerlaken, M. (2020). It matters what designs design designs: speculations on multispecies worlding. Global Discourse. https://doi.org/10.1332/204378920x16032019312511