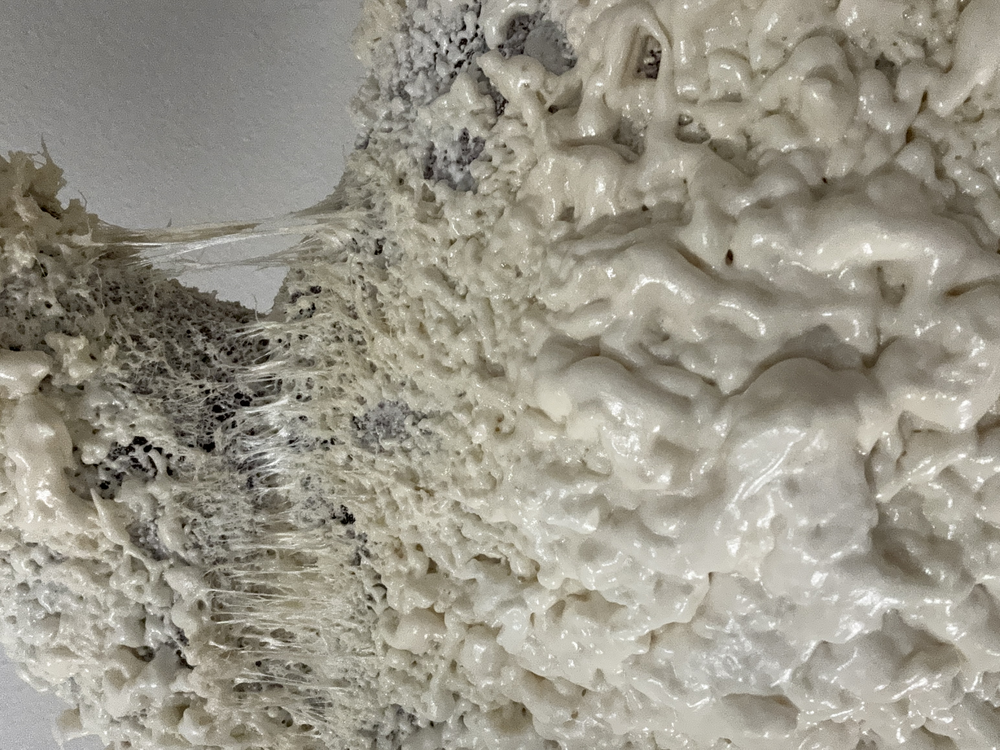

In order to apply the material onto my body, I first had to protect my skin with plastic film. The first piece of foam I applied over a long-sleeved elastane shirt, and once the material dried, it became so rigid that I had to ask for help to get out of that armor. The material turned every gesture into effort, embodying the way gender norms solidify into rigid roles. Yet, with time, the hardened foam cracked and fragmented, leaving residues on my skin and in the space—traces of instability that exposed the fragility of what at first appeared solid.

In this experimentation, I drew on Hélio Oiticica’s concept of the Parangolé, which he described not as costumes but as propositions for action.4 I cite Oiticica here not only for the visual or historical resonance of his work but for the methodological framework it offers: the emphasis on the body as the activator of the piece and on material as a co-creator of meaning. Within an artistic research context, this perspective allows me to approach foam not as a garment to be worn but as a proposition that reshapes movement, gesture, and relation. Wearing foam thus became a methodological inquiry into how body and material negotiate with one another, generating actions that neither could predetermine alone.

Which material could bring an artificial quality capable of exposing gender identity as constructed rather than given? And how could my body relate to this material? Provoked by Judith Butler's proposition, developed in opposition to essentialist feminist claims of a natural female identity, that the body is not a natural given but a construct shaped by social norms, with gender as one of its primary inscriptions, I began investigating materials that could embody this sense of artificiality, unnatural and constructed, seeking those that might act not just as props but as active agents. Drag queens' performances became a crucial point of observation, not only because their characters emerge through costumes and material excess, but because they lay bare the fact that gender itself is a costume, stitched together through parody, exaggeration, and performance. I analyzed how they mobilize the tension between natural and artificial, using parody and gesture to expose gender as a construction.

Drag shows became a point of observation, where I analyzed how performers use materials to reveal gender as costume rather than essence, and how they explore the duality of natural versus artificial through parody and gesture. As Judith Butler reminds us, “in imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself—as well as its contingency.”3 Watching the Wigstock documentary and Tabboo!’s performance, I encountered drag not simply as parody but as an innovative practice where costume and gesture expose the instability of gender norms. These works became my first point of inspiration. I began to wonder: could materials in my own performances work in a similar way, not simply as adornment, but as critical devices that expose the construction of identity?

This question led me to search for a material that could carry this artificial quality in its aesthetics, enabling the creation of a drag-inspired garment for rehearsal. Foam insulation became the center of my exploration, with many ideas circling around it. It stands for artificiality, expansion, rigidity, mask, cracking, entrapment, and transformation. These qualities overlap—rigidity is close to fragility, a mask can also break, and protection can turn into a trap. The material is never stable: it grows too much, hardens into shells, then cracks apart. In this way, foam is not just a material but a metaphor, showing how identity can be built, restricted, and also broken open. I began by experimenting with its application on flat and curved surfaces, studying how long it took the material to harden completely and how I should apply it in order to achieve the results I desired.

Foam insulation became the center of my exploration, with many ideas circling around it. It stands for artificiality, expansion, rigidity, mask, cracking, entrapment, and transformation. These qualities overlap; rigidity is close to fragility, a mask can also break, and protection can turn into a trap. The material is never stable: it grows too much, hardens into shells, then cracks apart. In this way, foam is not just a material but a metaphor, showing how identity can be built, restricted, and also broken open.

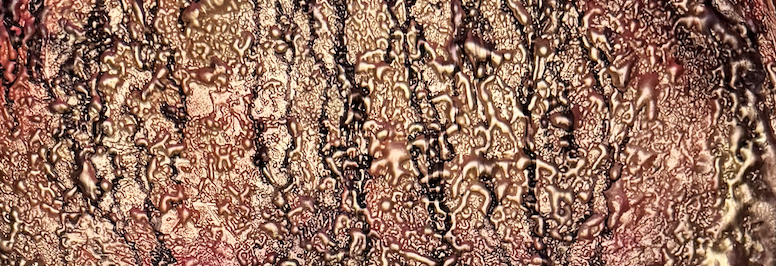

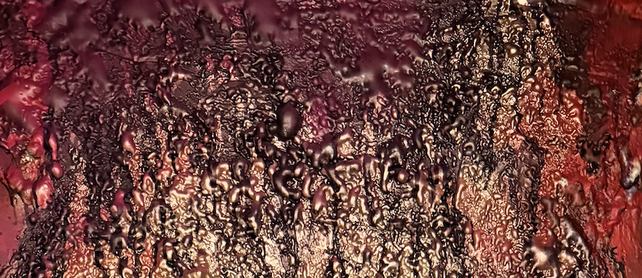

I experimented with foam’s artificial surface by spray-painting it in different colors and setting it against its original off-white. Spray polyurethane foam (SPF) is a synthetic polymer created when two liquid components, an isocyanate and a polyol resin, are mixed together. The reaction produces heat and rapid expansion, generating a foam with a cellular structure that hardens in place. This expansion, valued in construction for filling gaps and sealing against air and moisture, proved unpredictable in performance, swelling beyond control, spreading into lumps, and cracking as it cured.

There are two main types of spray foam: open-cell and closed-cell. Open-cell foam is softer, lighter, and more porous, often used for sound absorption but less effective as a moisture barrier. Closed-cell foam is denser and more rigid, with higher insulation value and water resistance, but less flexibility once cured. The insulation foams I used were manufactured in off-white or yellowish tones. Through repeated trials, I noticed that not only thickness but also brand affected the results: the foam’s expansion rate, cell density, and cured size varied significantly from one manufacturer to another. Thin layers hardened quickly and became brittle, while thicker pours held volume but risked collapsing or detaching.

Once I began applying the material onto my body, I first dressed in a second skin made of leggings and a long-sleeved top in elastane. I chose this fabric because its stretch made it easier to dress. Even so, once the foam hardened, the layer became very rigid, and I often needed help to remove it. On top of this surface, the foam became not only an external layer but a resistant shell. It clung, stiffened, and fractured with movement, restricting my gestures and demanding adjustments to my choreography. What began as a technical study—testing color, type, thickness, brand, and evolved into a process where the material itself dictated the conditions of interaction.

Gradually, I started to notice how this material could also resonate with the questions I was raising. Foam is strikingly unnatural, not only in its chemical composition but also in its visual aspect once it expands. As it hardens, it restricts and limits movement, which began to suggest a metaphor for how gender performance solidifies into rigid roles that constrain bodily freedom. Yet, when applied to a surface in motion, the foam eventually grows brittle and begins to crack, leaving behind traces and residues, material reminders that expose the instability and artificiality of what at first appears solid.

When I first began rehearsing how to wear this body, I had no sense of how difficult it would be to enter it. Very quickly, I realized that the act of putting on the rigid shell was already performance: the struggle to inhabit the form became inseparable from the work itself. Another discovery that emerged in experimentation was the peculiar sound the foam produced — a constant cracking, as if the material were resisting the act of embodiment. This auditory dimension underscored the instability of the structure, making the process of wearing it an encounter with fracture as much as with form.

Wearing the foam revealed limitations that I could integrate into the vocabulary of gestures. The friction between two surfaces, my body and the foam body, staged a dialogue of oppositions. Molded from my own form, it was never truly mine: simultaneously inhabited and alien. The foam carried the imprint of my body and could only exist through my presence, yet its rigidity imposed strict limits on movement, dictating how gestures unfolded.

In this sense, the foam body functioned as both material experiment and critical metaphor. It embodied the paradox Judith Butler identifies in the way gender norms materialize on the body, producing a recognizable form of subjectivity while simultaneously constraining the possibilities of its expression.5 The performance thus became an embodied inquiry into how subjectivity is shaped at once through inhabitation and restriction, presence and resistance.