Butler’s notion that gender is produced through repetition, and that the unconscious reiteration of gestures and patterns creates the illusion of naturalness6, became a guiding principle in my process. Throughout the time I was inside the foam body, I kept repeating the phrase “It’s natural” like a mantra, as if trying to convince myself of what was visibly contradicted by the body’s uncomfortable and artificial appearance. This tension between words and image marked my first experimentation with parody, using contradiction to expose the gap between what is said to be natural and what is experienced as constructed.

I began testing how repetition itself could operate as both method and reflection. I incorporated the phrase It’s Natural into each movement, using it as a refrain to probe the tension between gesture and language. This experiment functioned as parody and commentary at once: on the one hand, emphasizing the contrast between my restricted, difficult movements and the verbal insistence on naturalness; on the other, serving as a way of persuading myself, and perhaps the audience, to temporarily inhabit the fantasy of gender identity.

The oppositional relationship between gesture and material unfolded into a restrictive quality in my movements, and the struggle to fit inside that mold carried multiple symbolic layers that I could further expand by emphasizing the tension between the natural and the artificial. This paradoxical and conflictual relation—between being occupied and delimited—led me to recognize how parody in drag performance makes this tension felt in a more experiential way. Scholars of drag have pointed out how exaggeration and distortion of gestures create openings in the illusion of naturalness, exposing gender as repetition rather than essence.7 By repeating gender with intentional exaggerations, distortions, and even “wrong” gestures, drag opens up cracks in the illusion of naturalness. In doing so, it stages gender not as essence but as repetition, a repetition that always carries the possibility of error, of doing it differently, and thereby of unsettling the very norms that seek to fix and constrain the body.

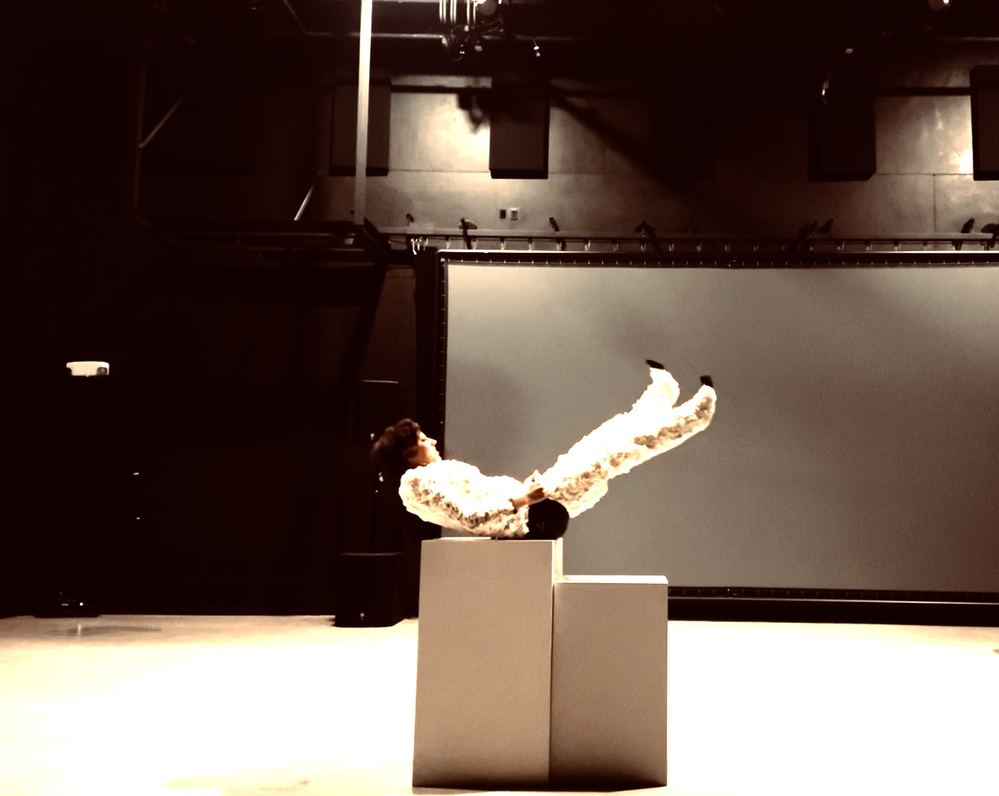

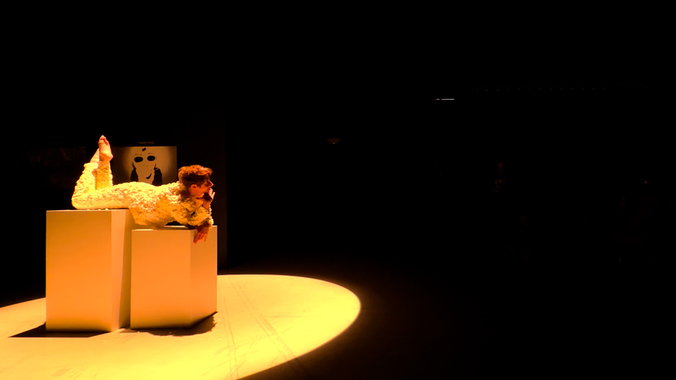

From there, I began to embody this ironic relation with the ultra-rigid foam body by composing movements and gestures that deliberately spoke the opposite. I started experimenting with how I might make the performance appear natural and effortless, while at the same time remaining obviously uncomfortable and absurd. This led me to research sculptural poses and translate them into my movements, especially poses of relaxation, as a way of exploring bodies that seem to project ease while in fact concealing tension.

Which elements turn the Struggle of inhabiting the foam body into a theatrical metaphor? The use of the pedestal acquired an additional meaning throughout the rehearsal process. At first, it was only a practical tool to help me enter the foam body. But through documentation and watching the rehearsal videos, I began to see the pedestal as carrying a stage-like quality, turning the act into a performance rather than just an exercise. This recognition led me to expand the experiment by introducing another theatrical device, the spotlight, which brought its own symbolic weight, reinforcing the sense of staging and connecting the work more directly to the language of gender as a mimesis.

I realized the performance had two parts. The first was the physical struggle, the exhausting effort of entering and carrying the foam body. The second began once I was inside it: figuring out how to live with its difficulty and turn that restriction into gestures that looked like the opposite, as if comfort were possible within constraint. This reversal led me to create a sequence of poses that contradicted the sound and appearance of the foam body. The material continued to resist me, every movement producing an uncomfortable noise, every gesture marked by friction, yet by inhabiting it and repeating those poses with my own voice, I came to understand the foam body as a structure that revealed meaning only through the act of being lived in abrasion. In this sense, the performance echoed Butler’s idea that identity materializes only through reiteration, and it was precisely the opposition between effort and ease, discomfort and display, that made the construction of gender perceptible. As Paula Braga observes, some of the Parangolé capes “play with the awareness of suffering and simultaneous aesthetic joy” and call for a shift from transcendence to immanence, stressing the participant’s full state of being in the world.7 In this sense, the foam body echoed that logic: each gesture was at once constraining and generative, never offering escape but instead producing an immanent experience where parody and struggle coexisted.

This process also led me to question the audience's participation in this performance. If the audience does not experience the foam body with their own bodies, is their laughter and recognition still a form of participation? Or is it limited to a passive role? Following Jacques Rancière’s proposition of the “emancipated spectator,” I would argue that awareness itself constitutes a participatory act, even when the body remains external to the material.8 At the same time, the experience opened the possibility of reimagining the performance as a collective wearing act, where the trauma of restriction and the parody of posing could be distributed across multiple bodies. This tension between witnessing and inhabiting remains a crucial question in my ongoing exploration of participatory and collaborative practices.