All the information, knowledge and detail that is gained throughout the research related to technique, mental and physical processes and the main concepts of approaching sound, start to form a common language of communication between composer and performer. Even though we utilise lists, recordings of improvisations, notes and videos as part of documenting and structuring experimentation, the goal remains to attain the embodiment of a specific practice, which is to be achieved by an ever evolving training. Once the practice starts becoming part of the musician’s habitus, we can mainly work with embodied memory. Rebecca Schneider discusses the qualitative differences between archive and memory in the arts. She argues that the constant efforts of maintaining and preserving a performance by documenting it in whatever way, defies the power of ephemerality, the ability of a performance moment to evade materiality (Schneider 2012). In the archive culture of the West, specifically in music, notation and the traditional score are to serve mainly the purpose of representing in the most accurate way possible what music should sound like, in order for it to be reproducible. It focuses on describing the sound result. In different cultures throughout history, however, there have been various approaches of notating. Tibetan chants notation focused on the movement of the voice; Byzantine chants notation is differential in the pitch representation, describing relations among notes, as well as qualities of the voice’s tone; Western music notation utilises an absolute representation of pitch; more contemporary notation systems attempt to depict also physical components of sound production.7 In general terms, notation is a way of expressing and reflecting thought. The information contained in a notation and the way this information is expressed in writing indicates the order of priorities, but also what purpose the score is intended to serve. In the context of this project’s practice, notation, even though it is not present from the beginning, is shaped parallel with the research process and constantly interacts with the unfolding progress of the knowledge. Practice informs notation and notation informs practice. In principle, notation here does not seek to describe sound, nor to depict an exact timeline of events. It rather introduces an environment of action-based elements, in which the musician performs according to the training leading up to the performance.

- Tim Ingold in his book Lines: A Brief History dedicates a chapter to the relation between language, music and notation. He writes extensively about the intimate and organic link between language and its music and sound. He discusses instances of cultures where reading written text functions as an act of remembering, or looking at written signs can activate hearing. Throughout this chapter, he explains the strong connection between vision and hearing in the context of notation, and how this connection has decayed through time. (Ingold 2016, 6–28)

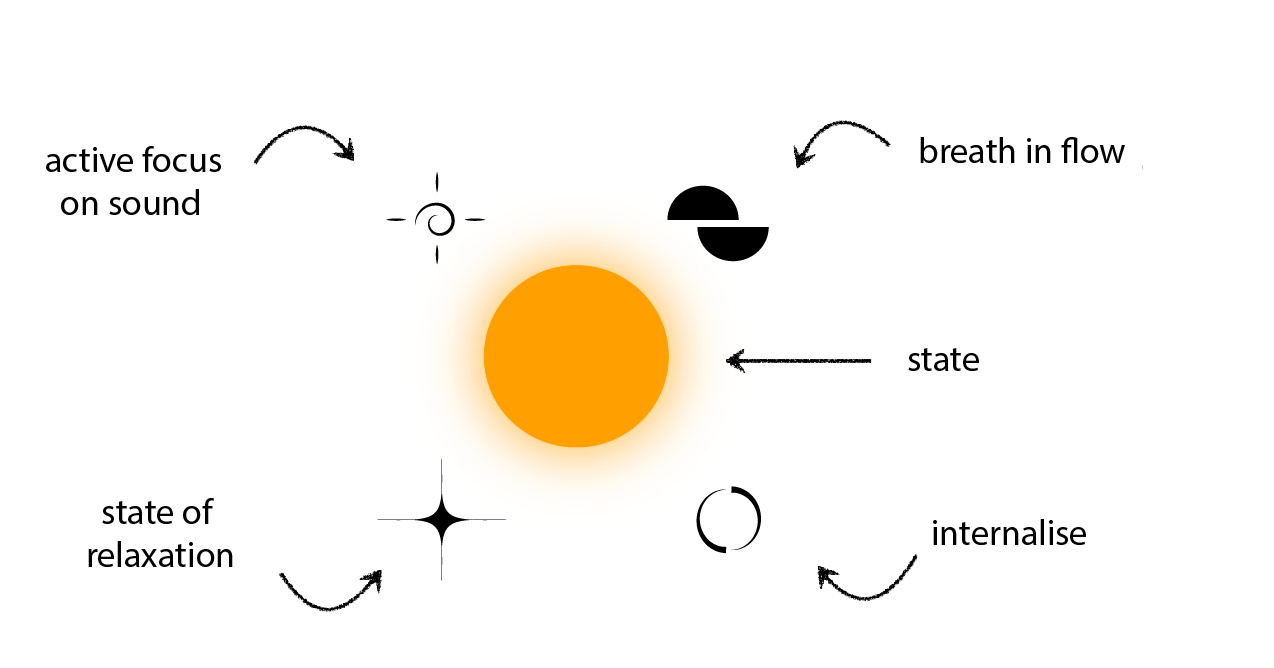

More concretely, the structure of notation that is being developed throughout most of the projects of this research (Artefact 2–4) is conceptually influenced by the notion of verticality of human thought manifestation (Small 1998, 50–63)8 and the spatially compact meanings of ideograms.9 In the notation system, concepts are not notated linearly and in detail, but are encapsulated and condensed into complex, often multidimensional figures, which describe either a state or a process. Each figure contains information about qualities of movement, thought, breath, sensations, texture and space perception. If we take a look at the first version of notation for the singer10 (Fig. 5), at the centre of the figure is the symbol that indicates that the action is to be thought of and carried out as a state, i.e. as a non-goal oriented moment. This main symbol is surrounded by four other signs that refer to the different qualities of the action. 1) Active focus on sound: the focus of the singer should be on shaping the sound that she produces. 2) Breath in flow: the singer should inhale and exhale equally with sound. 3) State of relaxation: the action has to be performed in a relaxed body state, meaning mainly the location where the sound is produced. 4) Internalised action: the focus and the sound are to be kept intimate and to oneself.

- Small in this chapter discusses the human effort to express meaning through language and gesture. Thoughts in the human mind manifest in a vertical manner, in a non-linear way. He analyses the translation of thought in language of words, where meaning is broken down into units, and is stretched out horizontally in time, and compares it with the language of gestures, which seems to be able to carry out the metaphorical and non-linear nature of thought.

- Ideograms are representations of concepts or ideas in a non-linear way, which can also combine multiple concepts within the same space.

- This refers to the piece Fact 4 (2024) for singer Helena Sorokina-Kogler and percussionist Manuel Alcaraz Clemente.

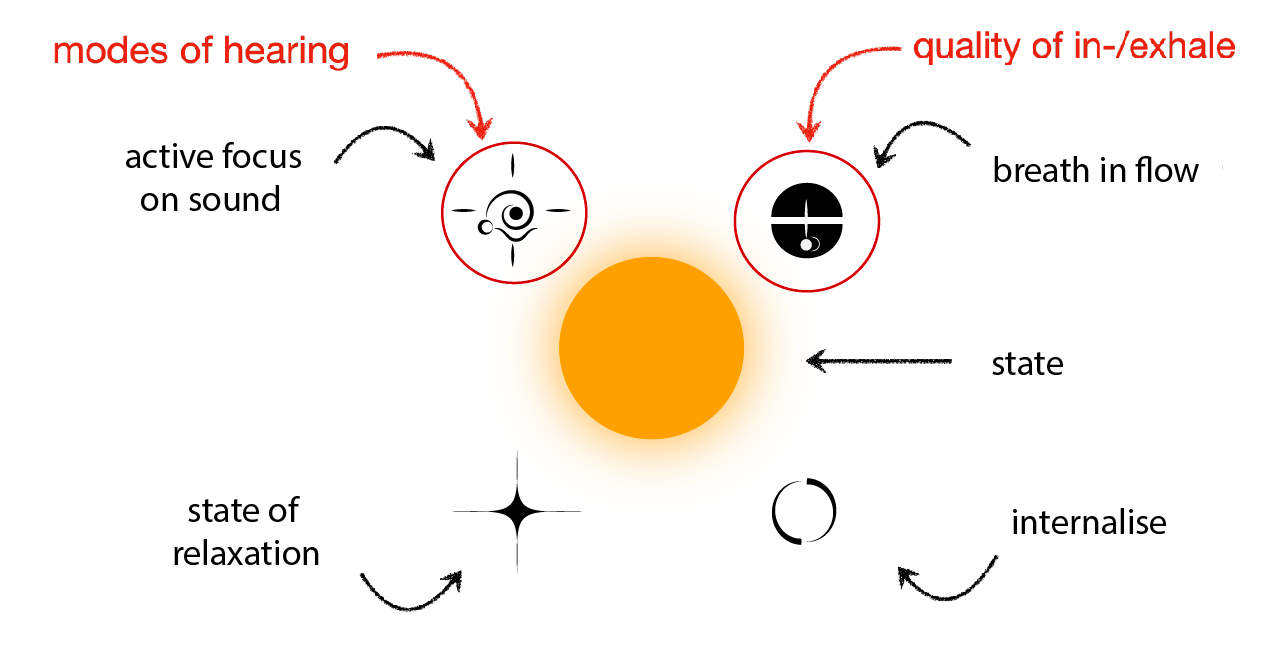

After the observations discussed in the video excerpts of Figs. 3 and 4, it seemed potentially fruitful to integrate two new possibilities of action, or more refined conscious focus into the practice, namely the focus on different modes of hearing, and the different patterns of breathing in flow. At this point, there seems to be a necessity for evolving and refining certain signs in the notation (Fig. 6). The sign that stands for the active focus on sound has to be differentiated, to indicate when the mental focus on sound is to be performed by means of activating the three modes of hearing. Furthermore, the sign expressing that the breathing is in flow would have to indicate more concretely what quality the articulation of this action should have. Thus, variations were developed that give the performer more information about the patterns of the breath in each instance.

As Schechner describes with regard to theatre making, the rehearsal process is a process of deconstruction and reconstruction, “[o]ld habits, the old body, old ways of thinking and doing are fiercely attacked, deconstructed and eliminated even, as new ways of doing, thinking, and feeling are being built” (Schechner 1994, 643). While the singer in Artefact 4 is continuously being trained to think in an alternative way about singing, to zoom in and engage with her body processes, perform them and make them audible, the score is there to visually-poetically depict the process, and create a basis of communication between performer and composer. During extensive rehearsing time together, the specifics of the performance are eventually being sculpted by observations of bodily and sonic manifestation that eventually become an embodied score within and through the body of the performer. Performing becomes an act that balances between letting something happen and making something happen.