While the West marveled at the advances of science and paid attention to the ideas of this new rationalism and humanism, there were many rebels diffused in the society.14 The image of clarity, elegance, and rationalism was being defied not only by charlatans and magic makers, but also by philosophers like Johann Georg Hamann (1730-1788) and his pupil Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803). The former believed the ideals of the Enlightenment were “cutting reality into some kind of mathematically symmetrical pieces,” which he could not possibly agree with, for life could only be appreciated in non-mathematical terms.15 The latter opened a door into debates that dominated the philosophy and politics of future generations. Disagreeing with Kant’s conception of universalism, Herder upheld the argument that man acquired his identity through the notion of a collective - through the language, customs, superstitions, folk tales, and the folk music of their cultural surrounding. Man’s intrinsic necessity to express himself also became an essential part of his philosophy and played an important part in his theory of belonging. Relating expression to communication, and therefore to language, he maintained that personal expression and identity were inseparable from the experience of culture - that human beings were products of the so-called Volkgeist.16 Since Herder’s Germany was made up of small, independent German-speaking territories, it is no surprise that language became such a crucial focus in his theories of culture, for it was the one apparent thing that linked these territories. In a time that everything French was infiltrating every part of German society, Herder, like Johann Wolfgang van Goethe (1749-1832) and Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814), found it their duty to promote the German language, for “every language bears the stamp of the mind and character of a national group.”17

Herder marks the beginnings of the nationalism that are still present today, which, as will be discussed in later chapters, become an essential element of Romanticism in the 19th century. German nationalism in the late 18th century was evident in the movement of Sturm und Drang, a new kind of expression that sought to show the impulses of imagination and the irrational.18 Though the Enlightenment promoted the message that reason was the way forward, people came to terms with the idea that “nature imposed her obscure and unfathomable will on man.”19 Recalling the opening of Joseph Haydn’s (1732-1809) Symphony 39 in G minor, or Symphony 49 in F minor, we can feel the turbulence and inner psychological distress. Though the language is clearly based the principles of the Classical style (regular phrase lengths, clearly marked cadences, etc.), there is a shift of expression that does not fit with the aesthetics of the merry and elegant courts. The realism of that century was transformed into a “human reality, in which nature and things are impregnated with human vitality, and vice versa” - as Herder declared, a poet was meant to “create illusion, to impose his own world on us.”20 The following excerpt from Goethe’s “Prometheus” is a classic example of this necessity:

Wer half mir

Wider der Titanen Übermut?

Wer rettete vom Tode mich,

Von Sklaverei?

Hast du nicht alles selbst vollendet,

Heilig glühend Herz?

Und glühtest jung und gut,

Betrogen, Rettungsdank

Dem Schlafenden da droben?

Ich dich ehren? Wofür?

Hast du die Schmerzen gelindert

Je des Beladenen?

Hast du die Tränen gestillet

Je des Geängsteten?

Hat nicht mich zum Manne geschmiedet

Die allmächtige Zeit

Und das ewige Schicksal,

Meine Herrn und deine?

Wähntest du etwa,

Ich sollte das Leben hassen,

In Wüsten fliehen,

Weil nicht alle

Blütenträume reiften?

Hier sitz’ ich, forme Menschen

Nach meinem Bilde,

Ein Geschlecht, das mir gleich sei,

Zu leiden, zu weinen,

Zu geniessen und zu freuen sich

Und dein nicht zu achten,

Wie ich!

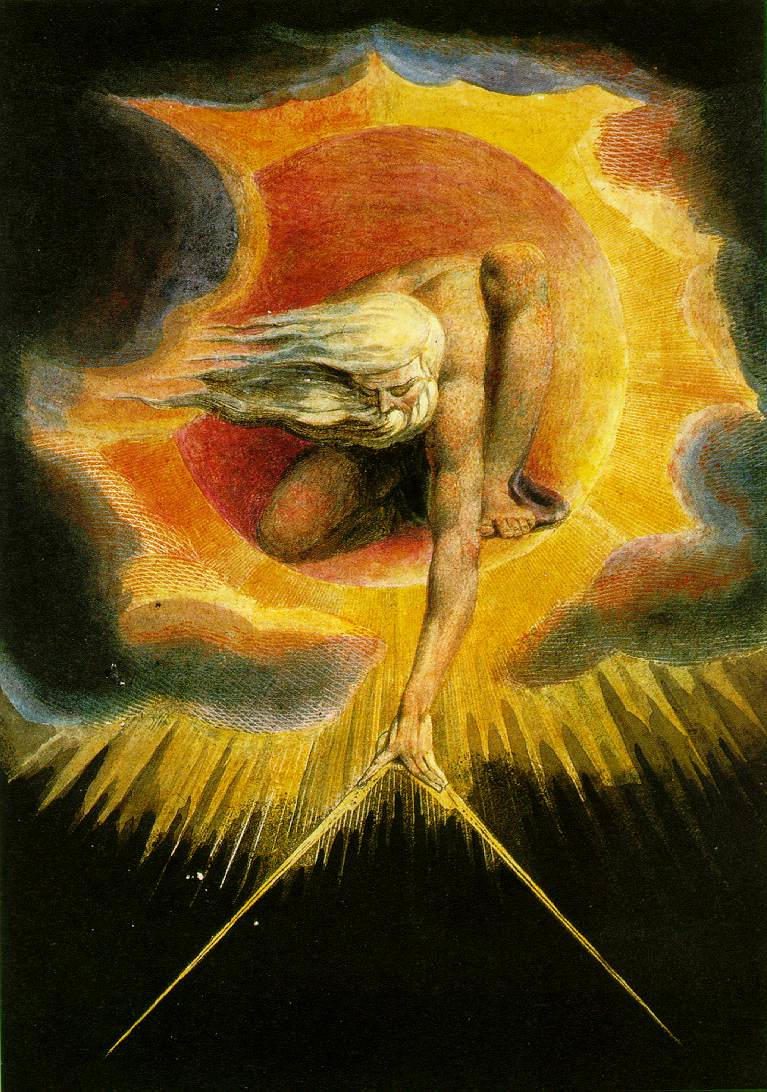

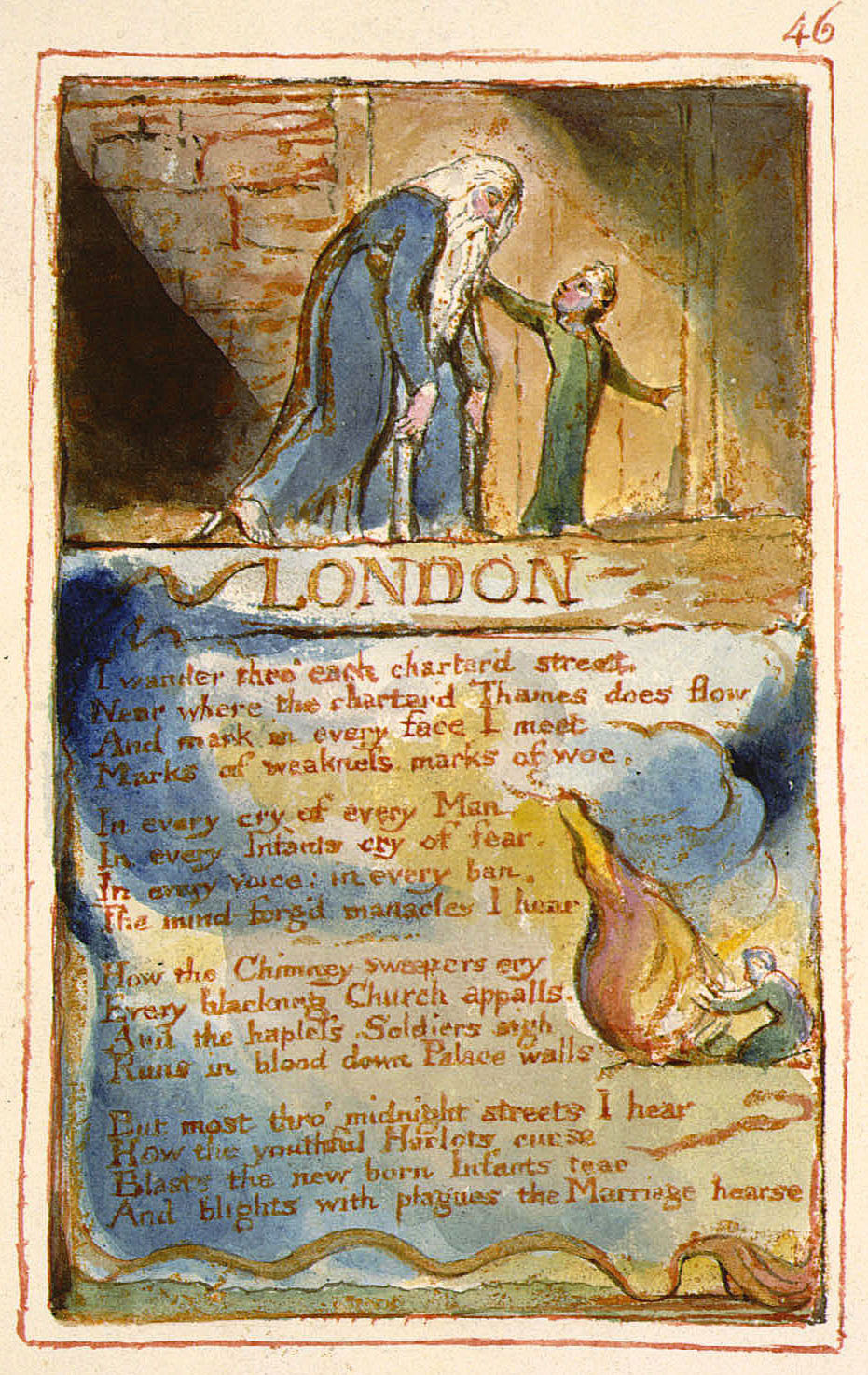

This spirit of Romanticism was also very much apparent outside German society. John Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), a Swiss-born painter who fled to England in search of freedom after being ordained a minister at the age of twenty, left a mark on the history of art. Though he was an admirer of principles of Neo-classicism, he used his fantasy to take us to the “dark recesses of the mind,” as seen in his The Nightmare (Figure 3).22 William Blake (1757-1827), a visionary and radical in English society, was another exemplary case of an artist who saw the imagination and expression as the key to human existence and the “source of mankind’s redemption."23 Being a student at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, like Fuseli, he was expected to work within the boundaries of their Neo-classical tradition, but his imagination and vision did not allow him to acquiesce. Circa 1788, Blake invented a new method for printmaking, the relief-etching, which allowed him to combine images and text in one platform. His “London” from Songs of Experience (Figure 4), shows this union of text and image, recounting the disgust for urban modern life. He used this medium to create books that “engaged the most pressing moral and political questions of the day, including revolution, sexual freedom and the slave trade.”24 His Ancient of Days (Figure 5) shows Urizen from the heavens setting a compass upon the earth, as if curtailing human’s freedom of thought and imagination.

Indeed, the end of the 18th century was a time of great turbulence, filled with confusion and political unrest, including several revolutions, not to mention a change in economics with the rise of the Industrial Revolution. When Rousseau wrote “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains,”25 in 1762 had the force to propel people to desire and fight for their freedoms of “thought, of freedom, of worship, of speech, and of taste.”26 Blake, had a clear vision of this when he wrote that “poetry fetter’d, fetters the human race.”27

Who helped me

Withstand the Titans’ insolence?

Who saved me from death

And slavery?

Did you not accomplish all this yourself,

Sacred glowing heart?

And did you not – young, innocent,

Deceived – glow with gratitude for your deliverance

To that slumber in the skies?

I honour you? Why?

Did you ever soothe the anguish

That weighed me down?

Did you ever dry my tears

When I was terrified?

Was I not forged into manhood

By all-powerful Time

And everlasting Fate,

My masters and yours?

Did you suppose

I should hate life,

Flee into the wilderness,

Because not all

My blossoming dreams bore fruit?

Here I sit, making men

In my own image,

A race that shall be like me,

That shall suffer, weep,

Know joy and delight,

And ignore you

As I do!21