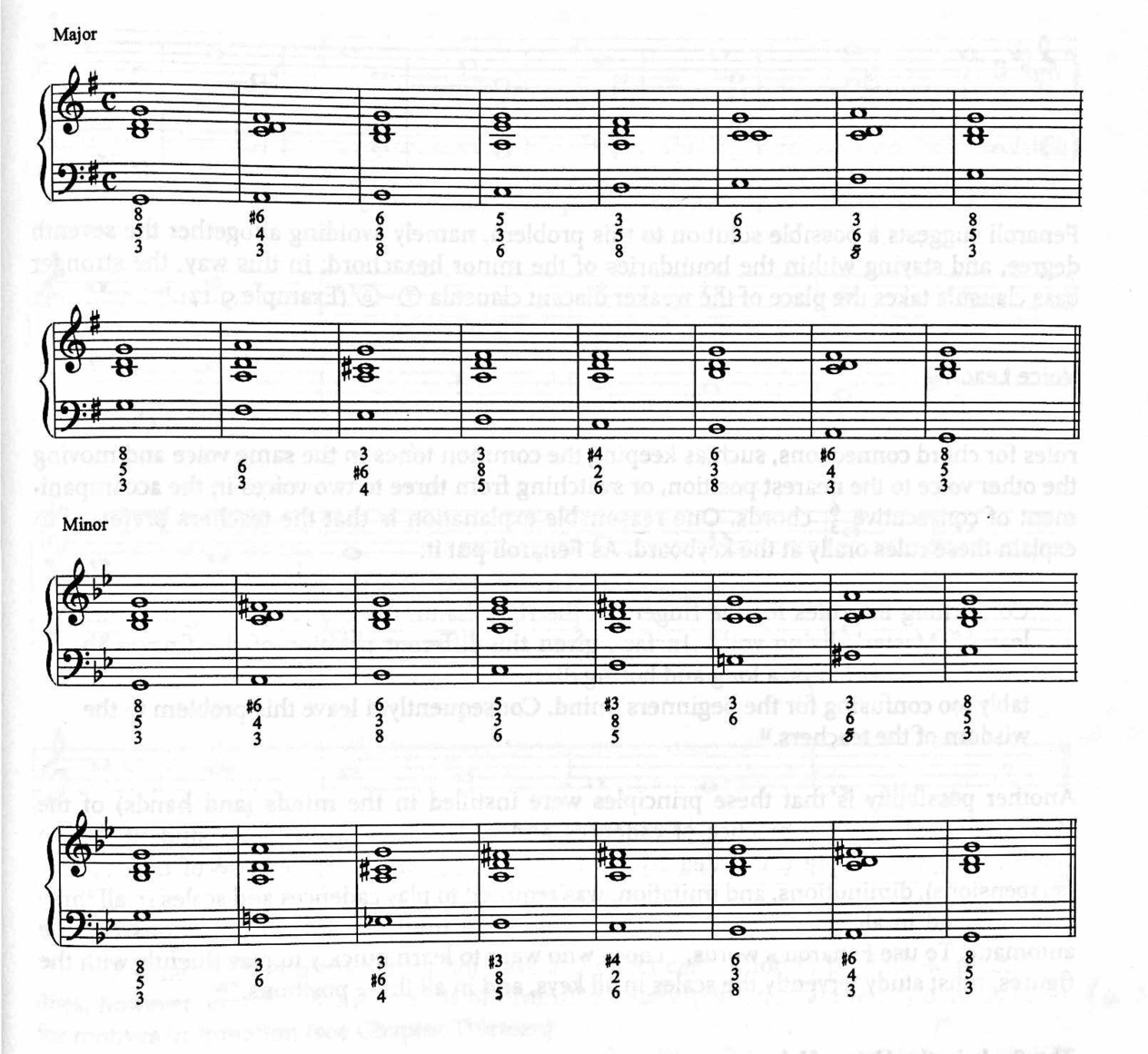

Returning to the previous subject of scales - the rule of the octave was developed as a system that assigned specific chords to each of the scale degrees. The figurations basically showing us which intervals one could execute in relationship to the bass. Different maestri had different ways of harmonizing these scales throughout the years, but Fenaroli’s version became the prominent one by the second half of the 18th century.1 This rule is “more than an ingenious tool for accompaniment of a scale; it is a powerful means of tonal coherence.”2

FIGURE 6 Fenaroli’s version of the regola dell’ottava in major and minor, taken from Giorgio Sanguinetti’s The Art of Partimento, 115

As a cellist, the obvious way to put this into practice is to arpeggiate the chords from the bass up and down the scale in different keys. It is important at the beginning to keep the intervals as close as possible in one position, so that one can become familiar with the different shapes that these chords take in one's hands.

Once this becomes more or less natural, one can start adding passing tones and neighbor notes around these arpeggios, which can add more of a sense of music making with these exercises. For each full cycle (of the scale), assign a different rhythm, time signature, and character - this will also allow one to expand one's tool box and creativity within the confines of the harmonies.

The following step would be to move more freely between octaves and different positions. Start with mere arpeggiations in order to explore and find what possibilities are available. Little by little consciously start adding embellishments (as in the exercise before), to create more versatility in the approach to this scale.

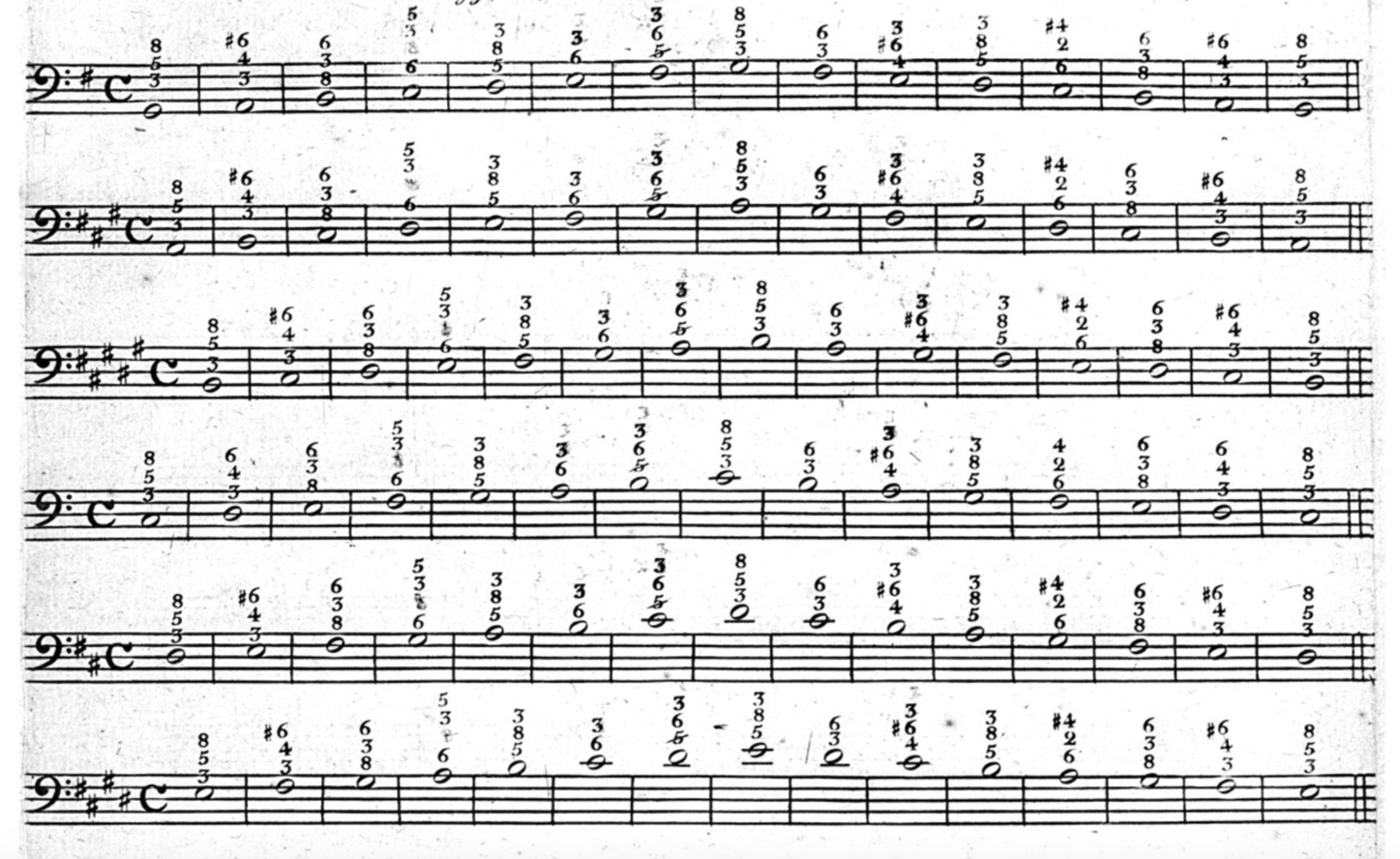

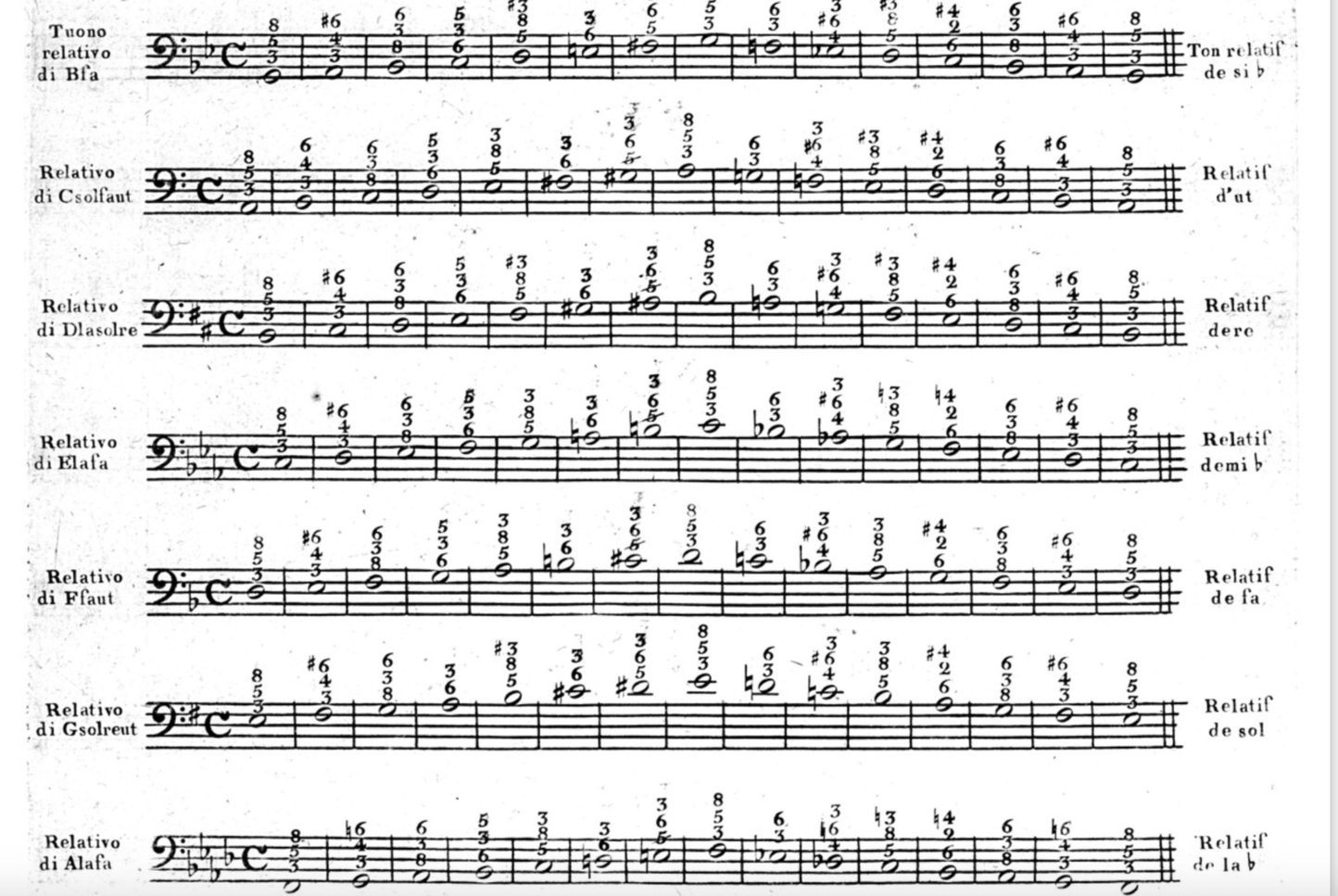

Below are the figured scales from Fenaroli’s treatise, and use them as a guide to practice the rule of the octave in the different keys.

FIGURE 7 Fenaroli’s Book 1 of Partimento ossia Basso Numerato, 50

A Scales in the major mode

Example using a Gigue rhythm Example using a Siciliana rhythm

Also becoming familiar with the regola dell’ottava, create different bass lines and practice improvising over them with the same principles, keeping in mind the harmonizations that could be used with each scale degree.

Returning to the previous subject of scales - the rule of the octave was developed as a system that assigned specific chords to each of the scale degrees. The figurations basically showing us which intervals one could execute in relationship to the bass. Different maestri had different ways of harmonizing these scales throughout the years, but Fenaroli’s version became the prominent one by the second half of the 18th century.1 This rule is “more than an ingenious tool for accompaniment of a scale; it is a powerful means of tonal coherence.”2

FIGURE 6 Fenaroli’s version of the regola dell’ottava in major and minor, taken from Giorgio Sanguinetti’s The Art of Partimento, 115

As a cellist, the obvious way to put this into practice is to arpeggiate the chords from the bass up and down the scale in different keys. It is important at the beginning to keep the intervals as close as possible in one position, so that one can become familiar with the different shapes that these chords take in one's hands.

Once this becomes more or less natural, one can start adding passing tones and neighbor notes around these arpeggios, which can add more of a sense of music making with these exercises. For each full cycle (of the scale), assign a different rhythm, time signature, and character - this will also allow one to expand one's tool box and creativity within the confines of the harmonies.

The following step would be to move more freely between octaves and different positions. Start with mere arpeggiations in order to explore and find what possibilities are available. Little by little consciously start adding embellishments (as in the exercise before), to create more versatility in the approach to this scale.

Below are the figured scales from Fenaroli’s treatise, and use them as a guide to practice the rule of the octave in the different keys.

FIGURE 7 Fenaroli’s Book 1 of Partimento ossia Basso Numerato, 50

A Scales in the major mode

B Scales in the minor mode

Example using a Gigue rhythm Example using a Siciliana rhythm

Also becoming familiar with the regola dell’ottava, create different bass lines and practice improvising over them with the same principles, keeping in mind the harmonizations that could be used with each scale degree.