Principles of Practice

What is practice as defined here? There are two layers of practice that are unfolded and inquired into:

1. The creative practices of visual art and writing.

2. Crafting consciousness through and as artistic practice

A curated set of principles have therefore been created in order to engage with porosity as a practice of crafting consciousness, and to make tangible and visible practices of visual art and writing. Sādhanā, the Sanskrit word for practice, is a spiritual and meditative practice, where the artist seeks to immerse herself in a state of transcendence or oneness with the universal consciousness through her creative practice. The curated set unravels the terse meaning of the word Sādhanā to activate each aspect of this word and build a more comprehensive practice.

Why does one need principles of practice?

There is both complexity and paradox in every creative act. The intuitive flashes and insights that emerge in seemingly unconnected moments help us to see certain patterns or orders that can inform and create a space in our consciousness for creative moments. Porosity is a specific state of consciousness and often elusive to reach and experience. The principles of engagement help to keep this state open, while the principles of practice allow these elusive experiences to be acknowledged, articulated, and crafted into visual or written form.

How do they work?

Principles of practice as outlined here are a curated set emerging from the cultural-philosophical framework outlined in the introduction. These seven principles are non-linear in their relationship with each other, but they do act as intricate web of ideas that work as a set and not independently. While it may appear that individual works/sketches could be through one or another principle of practice, a body of work that evolves under the framework of porosity would use the entire set in its evolution.

What are they?

My practice emerges through seven key principles: artistic reflection, ritual practice, philosophical inquiry, metaphysical embodiment, physical transience, mythological storytelling, and aesthetic play. Through movement, text, and image, through gardening, walking, pausing, and listening, I build everyday practices that become my grounds for artistic inquiry and research. ‘Movement is a continuous problem to deal with in painting. A painting is a static image, but the construction of a painting is performative,’ says artist Catrin Webster, who goes on to write about how performance painting turns into a meditative process when capturing her journeys through the Welsh landscape.(Merriman and Webster, 2009).

“We experience life through our senses, this I’d call real experience, first hand engagement with the world around us in the moment. I see my arts practice as increasing opportunity for such engagement, art as a doorway between our inner and outer worlds.” — (Keating, n.d.)

Our acts of perception emerge from simple embodied everyday actions like walking, driving, looking through a window, digging, planting, or composting. In Richard Keating’s work, he uses ‘art-walking’ practice as a way of place-making and developing landscape aesthetics (Keating, 2014). Actions and art-making are entwined in my practice, as actions themselves become line, space and form, and performative art. (Ilango & Kalyan, 2015). Webster points out how travel journeys, repeating a certain journey or circuit, also takes the form of a drawn line (Webster, 2012). My work draws on the interconnectedness between everyday actions and engagement, and the principles of practice to emerge an art of transforming consciousness.

Artistic reflection: Reflection through the practice of art. Reflections occur through the creation of form and the diverse artistic processes involved in the act of making. Sometimes form itself is the reflection, be it text, image, or movement. Reflection allows for intrinsic action in artistic practice and sometimes extends to everyday action as well. A thoughtful awareness of practice leads to artistic reflection. Drawing from meditative practices of the arts, yoga, and vedanta, reflection here is the process of consciousness reflecting on itself. This is critical for a practice of porosity, as it is built on a correspondence between inner and outer. For example, this paradoxical process is evoked through the iconography and symbolism of Śiva as the Lord of Dance, Natarāja. Natarāja dances in the heart of the devotee, indicated by a lotus at the base, yet he also dances in the expanse of the cosmos, as indicated by the aureole of flames that surround him. For the devotee, cit, consciousness is his interiority as well as the hall of consciousness, where Natarāja dances the citambalam. This ability for the cosmic, macro, universal consciousness to reside within the inner, micro, individual consciousness, and for one to be conscious of the other, is one of the best iconographic symbols of reflection and enlightenment within the tradition.

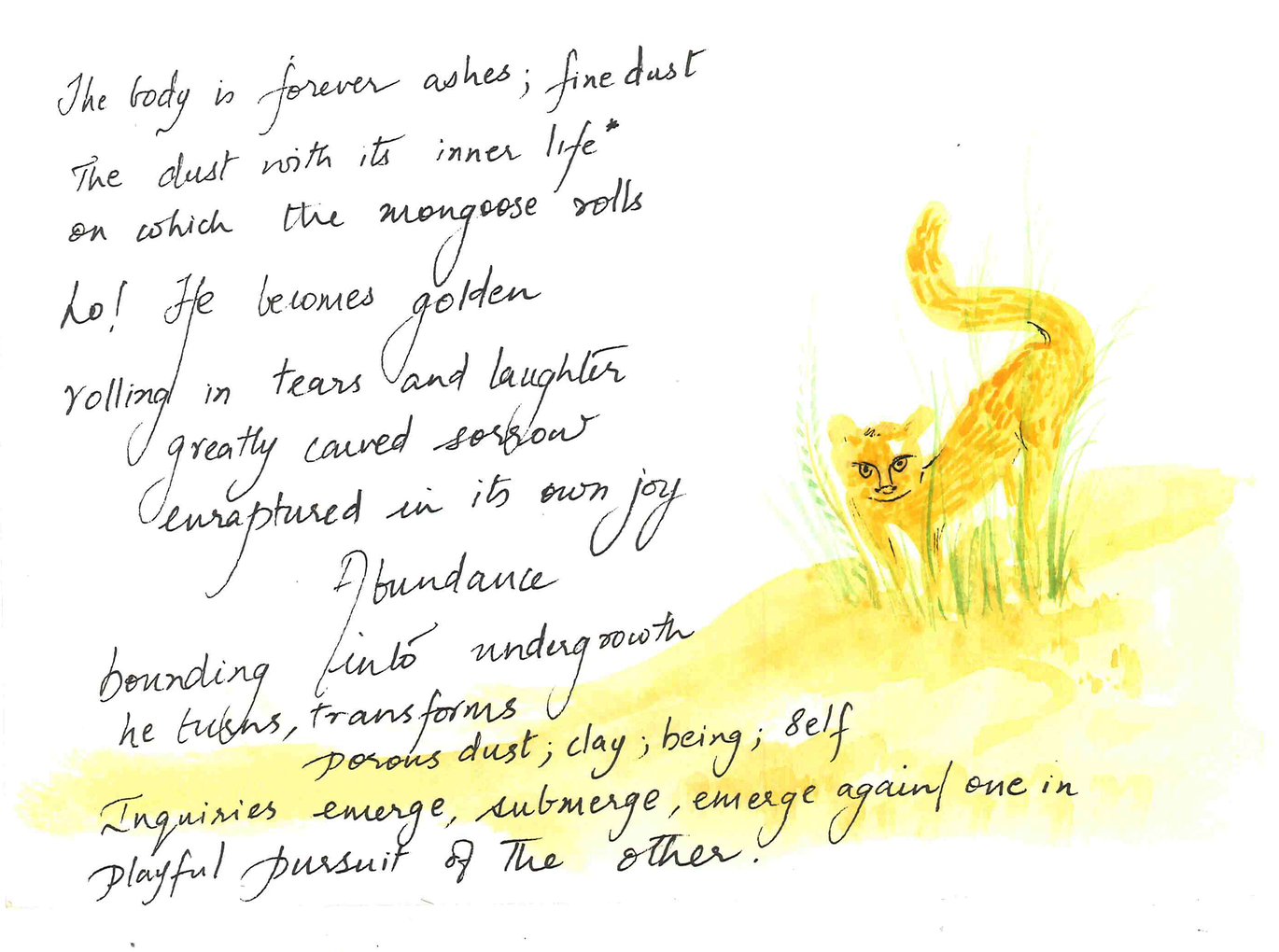

Ritual practice: Yajña and sādhanā are two words that denote intensive meditative practice in the Indian arts. Yajña also indicates transformation that an individual may experience through a creative process, as observed by Kak (2006). Practice in this light becomes an act of self-transformation and deep change within oneself. From walking quietly in natural spaces and listening to other beings to acts of painting, writing poetry, gardening, or composting, each action becomes a ritual practice of being, an aesthetic state of rasa in which correspondences are established between the microcosm and macrocosm. Rasa here is a state of being, the soul of a relationship between inner and outer. Time and space, when consecrated as yajña and sādhanā, become sacred, where exchange and continuum between self and cosmos become possible through symbols, myths, narratives, traditional knowledge systems, and notions of being (Vatsyayan, 1997).

Pages from journal, 2008, ‘Reflective Poem on Self’, drawing out the relationship between the inner and outer worlds.

The reflection draws upon the cultural perspective of the macro and micro as they are entwined and reflective of each other. This kind of reflection allows for a flow of consciousness that moves seamlessly across all beings and derives from both a cosmology and a highly developed symbolism in the Indian tradition.

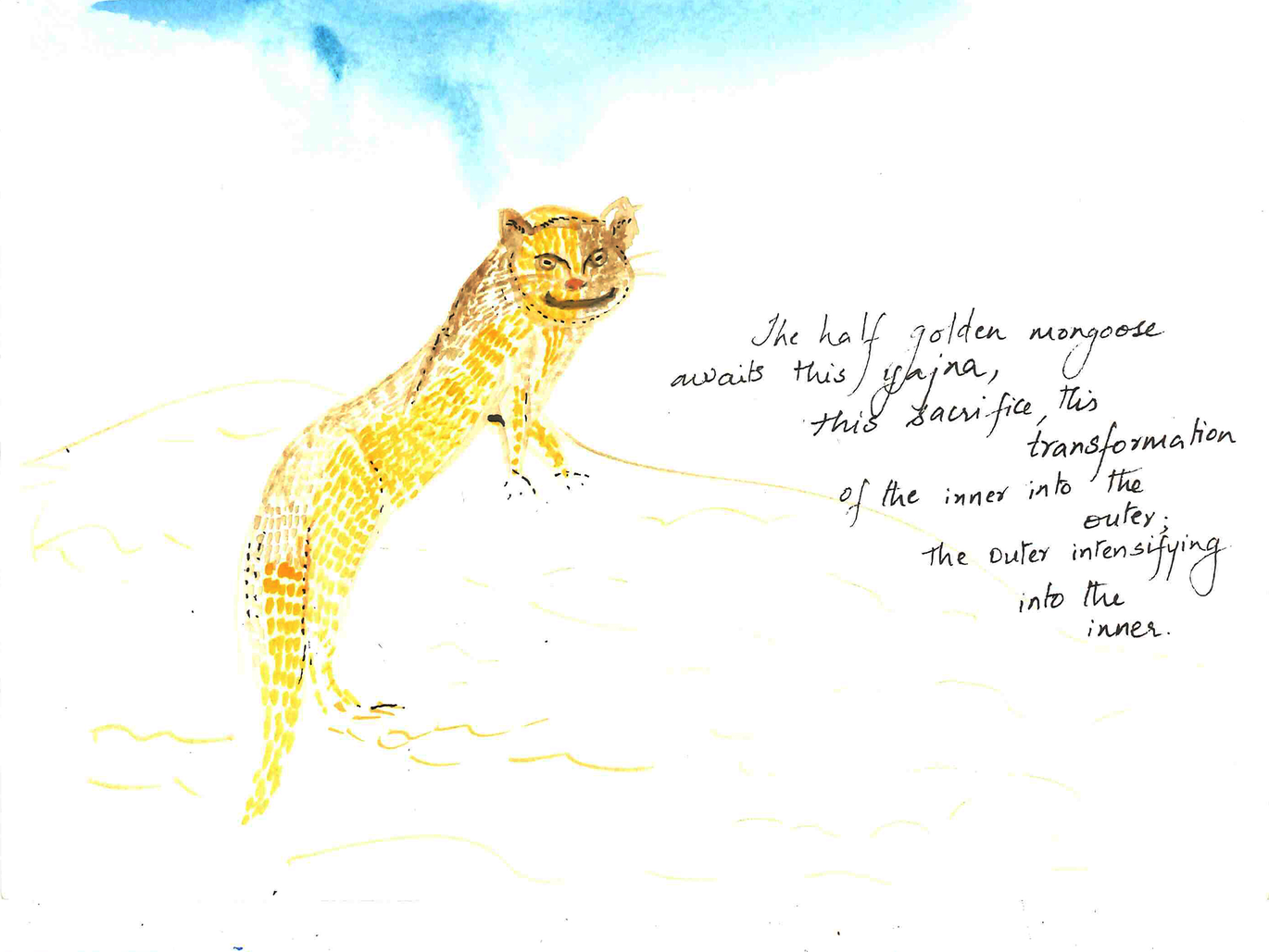

The artist’s enquiry is a unique process of research. The concerns here are many. But at the heart of this enquiry lies paradox, magic, and alchemy. The story of the half-golden mongoose in the Mahabharata talks about the essence of yajna, or sacrifice. A fundamental transformation requires simplicity of giving, of willing sacrifice rather than opulent show. The mongoose, in fact a cursed young man, had a body half made of gold, a quirk he’d acquired after rolling over food that an old man and his family had sacrificed to a guest, even though they had been hungry for a week. Later he attends King Yudishtira’s grand yajna. In vain, the mongoose attempts to transform the other half of his body into gold by rolling over the King’s sacrifice. Boldly he claims that Yudishtira’s yajna is false and does not stand up to the great level of sacrifice of the poor man’s yajna. As Indian stories go, rich in metaphor and perplexing, the mongoose remains a stark and important image in my mind. I chose the half-golden mongoose as a guiding light, the judge of this yajna. He also becomes the quiet inner voice, allowing me to characterise him, to invite him to join my journey so that I might seek the essence of transformation through him. He is a symbol of transformation, of sacrifice, of yajna. His straightforwardness, embodied experience, and bold pronouncement of what he considers a yajnamakes him a trustworthy voice.

The following poem (written in 2017), ‘Vac’, interprets the Hindu notion of the word as imbued with magic, mysticism, and profound mystery.

Visualised in Indian sculpture and painting in the form of a lion or a hybrid creature called Yali or Sardula, the power of the word and its meaning can be found in the Vedic goddess Vac. Drawing from the philosophy of Vac, the poem captures the essence of the relationship between word and meaning and extends them to questions of cognitive justice, culture, and identity.

Vac

Come reclaim me,

roaming wild spirit of lioness

of word and inner meaning

suffused, diffused

into this raw land

that unfolds

cradling you and me

like newborns;

like warriors

Give me back my

native tongue

the living flame of

my connections with my

land

and

sky

Come claim me

Vac, seething goddess

of word and meaning

ravage my senses

so I may come alive again,

let me ride on your

back

Mother, and mysterious

thread of consciousness

Let us roam across wilderness

of plundered land and abundant forest

Teach me again,

teach all that I have forgotten of my

people’s voices

Come reclaim me,

roaming wild spirit of lion

of word and inner meaning

suffused, diffused

into this inner

hall of consciousness.

-----------------------

Philosophical inquiry: Much of my artistic journey stems from philosophical enquiries into the nature of existence, self and being, the creation of meaning, and Indian speculative thought traditions. A philosophical approach to both art-making and ecological consciousness reframes my thinking within the realm of eco-ethics. This in turn impacts my play with form, technique, media, and material. Vital to Indian notions of philosophy is yoga, where mind and body, inner and outer align together. Artistic practice is also yoga.

Finding and connecting the profound and the mundane in everyday action is central to my work. This is also crafting of consciousness that arises from Tamil cultural notions of neṟi or muṟai. These two words/concepts may be interpreted as more than a tradition or a way of life, they imply ways of being, where the philosophical, sacred and the mundane everyday flow in a singular frame of responsible living. This is the idea of living tradition and daily practice at being human in Tamil culture. Philosophical inquiry is intrinsically embedded in these two concepts of neṟi and muṟai.

Yali and child playing with words, illustration for self-authored story ‘A pearl! A costly pearl! Did you find any?’ selected for the Katha Chitrakala Award 2005.