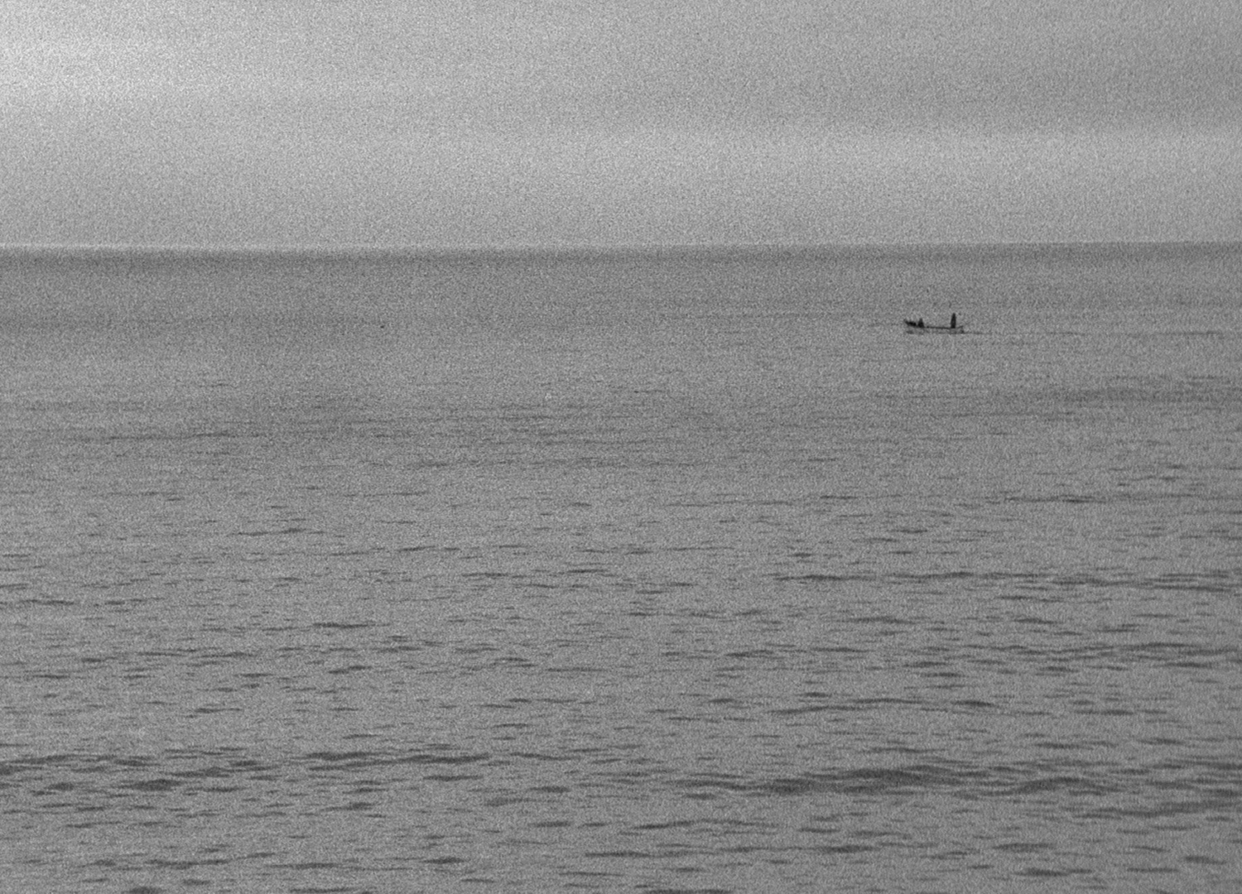

The opening shot in Days In Between, figuring a tiny boat with a single man floating on water as it enters the frame from the right, anticipates a stance that accompanied me throughout the whole time I have been involved with the film and the expanded form the project took on: consciously avoiding the placement of myself in the position of somebody who possesses power over his/her subject matter, of someone who knows. The fluid ribbon of water between the observer and the observed foretells this distance; so does the choice of a static shot from a tripod instead of more nonobjective, handheld cinematography. As a matter of fact it remains the case that, even today, I lack a considerable amount of knowledge of the complexities of the place’s histories, the entrenched conflicts and the region’s centuries old struggles. The film then, the ‘outcome’ - it remains disputable if there is a single one1

- cannot be representative of something, not even in its implicit critique of the western stigmatization of the region. Rather than claiming truth, and to avoid a totalizing historical narrative, it attempts to frame multiple realities in flux. There is a distrust implied here towards the reliability of the image to stand for the real, but also a skepticism towards the efficiency of the author to convey a streamlined, unifying narrative. The feeling of being on the outside of things, of coming to terms with difference and lack of understanding, occasioned a will to reinstate this sense of estrangement in the meeting with something unfamiliar and new. Conscious of my different location in regard to the places and histories with which I was implicated whilst researching and making the film meant overtly acknowledging and reflecting on the constrained, inhibiting and at the same time empowering location and condition from which I was to tell a story. Engaging with the strangeness and awkwardness of this ‘misfit’ condition that seems to move counter to an orthodoxy of form generated an interest in forms of ambiguity, discontinuity, and silencing; in processes commonly suppressed, or merely gone unnoticed.

A very distinct example of an expanded notion of in-betweenness can perhaps be described by the function the Kaiser-Panorama11 performed in the film and how it modulated the underlying process. Early on in the research we were captivated by a passage in Walter Benjamin’s Berlin Childhood around 1900. There, Benjamin expresses his relief that the image sequences in the Kaiser-Panorama were not accompanied by music, except for the automated sound between two pictures: “But there was a small, genuinely disturbing effect that seemed to me superior. This was the ringing of a little bell that sounded a few seconds before each picture moved off with a jolt, in order to make way first for an empty space and then for the next image.”12 Following this find we realized that Franz Kafka had noted in his diary entries of 1911 a similar observation, where he describes the time required to transport the images in the Kaiser-Panorama as the space which allows the viewer to stray from one scene before diving back to the next motionless subject. A mechanical element, he claims, holds sway over imagination.13 These two annotations triggered an association to Aby Warburg’s “thought-spaces” [Denkräume] that activate the space between image and spectator, a surge in the affective temporality of images, their inherent energy flows and their “survivals”. Such active, mobilizing gaps between the images can be traced in his Mnemosyne Atlas, a genealogical project seeking affinities - via temporal ruptures - between images diachronically. Warburg, widely known for his Pathosformeln that marked a cut, a twist in the comprehension of the relation of the Florentine Renaissance to Antiquity, raised questions of the iconology of the interval as an expression of a non-linear, topographic vision of history: in his 1929 journal he refers to his Mnemosyne Atlas as an “iconology of the intervals”.14 Georges Didi-Huberman sees the Mnemosyne Atlas “as a visual matrix for the multiplication of possible interpretations”.15 The black forms on the fabric can be perceived as not being a negative space, but rather a dynamic, positive terrain similar to a cut in cinematic montage that pairs two instances and places them into an expanded notional framework. It is within this spatial occurrence of in-betweenness that memory can emerge. As Philippe-Alain Michaud tellingly suggests, “To grasp what

The title Days In Between was not a foregone conclusion, we came to this decision relatively late in the process when the film was in post-production.3 It felt correspondent to one of the film’s most formative notions and points of address - that of the gap and the interstice.4 In-betweenness operates here on multiple, often divergent, intersubjective levels. The Balkans have been analyzed extensively by many scholars as “an enigmatic, impenetrable, impulsive and untamed psycho-geographic phenomenon”,5 a byword for hostility and synonymous with the ‘other’, the repressed flip-side of European history - in the words of Slavoj Žižek, “the screen on to which Europe projected its own repressed reverse.”6 The name itself goes back to a misunderstanding by a handful of European geographers in the early 19th century, who erroneously took the comparatively small mountain range of Stara Planina, (or the Balkan Mountains in Bulgaria, in Antiquity known as the Haemus Mount, a range that needed to be crossed on one’s way from Central Europe to Constantinople) to be a massive chain dominating Southeastern Europe. Like the Pyrenees that bound the Iberian Peninsula and separate it from continental Europe, Stara Planina was thought to stretch all the way from the Adria to the Black Sea.7 Moreover, the Balkans have - from different standpoints, but predominantly from the West - been seen as a liminal space, neither here nor there, neither West nor East. Travelers in the 18th and 19th centuries, unable to define the region with precision and certainty, preferred the more vague and less constraining term “lands

Warburg meant by the ‘iconology of the intervals’ one must try to understand, in terms of introspection and montage, what binds, or, inversely, separates, the motifs on the irregular black fields that isolate the images on the surface of the panels and bear witness to an enigmatic prediscursive purpose.” Michaud then goes on to analyze how these intervals serve as fault lines that “organize the representations into archipelagoes” in order to support his argument regarding the way Warburg introduces differences, and how he challenges the parameters of space and time in a cinematic approach, thereby transforming knowledge into a cosmological, infra-discursive configuration.16

A lengthy series of itineraries over four years turned into vectors of time lapses, at times crossing or overlapping which, by temporalizing space, came to connect into a destabilized reading of location, topography and history. It is here where the contemporaneity of the uncontemporaneous feeds in, the manifold temporal aspects and their intractability entangled in one’s understanding of heterogeneously crafted and fabricated places. The collision of the actuality of being there with the actualities that had been and those that were expected, or even anticipated, became a constant point of reference in the development of the project. Embracing vulnerability and resisting the idea of certitude by creating spaces for chance encounters to occur: such strategies aided in debunking the essayist’s authority to maintain a potent overview at all times. By de-centering one’s own subjectivity and abandoning the conception of a unitary self, a narrative topography of jagged storylines and submerged realities could now be deployed. Translated into the film’s materiality, this constant dis-placement and movement between fringe and center inscribed itself on the film emulsion producing a surface accountable to a process of doing, un-doing and re-doing. Thus the surface, similarly to history, cannot be affixed, or be congruent with itself.

The project consciously inhabits the dynamic space between two strands that it closely follows as it sways to and fro. The first mirrors the attempt to bring one’s personal voice - by both tuning in and effecting slippage - to another place with all the implications this endeavor entails, especially because (and this indicates the second strand) this ‘other place’ is a composite agglomeration of deeply rooted historical narratives and socio-political imaginaries. The impact of the collision that this inaccessibility of understanding occasions, and the trace it leaves over time, unfold in the visual, textual and auditory itineraries of the project. Whereas the first strand

in between”8 - a term that facilitated the cementation and perpetuation of a view that situated the ‘wild’ and ‘lawless’ countries as being between the two littoral zones. Marius Babias asserts that Carl Schmitt’s 1925 dispositive that saw the Balkans as a buffer zone between Europe and Asia, between Christianity and Islam, and between civilization and barbarism persists through to the present.9 By any standard the image of the Balkans rests upon dualistic concepts, fixed binaries and sets of antagonisms.

One of the questions the film asks is: What in our analytic frameworks would change if we were to think beyond such oppositional pairs and how can one deconstruct the essentialist view of center and periphery, here and there, we and the others? Trinh T. Minh-ha’s concept of “being of both - of here and there” aided me - especially in the research stage after shooting - in appreciating the potential within processes of de-familiarization and of “making strange” the dominant narratives through which we think we see our world(s). This guiding thread was complemented by a repeated questioning of the representative space that one occupies and from which one speaks or produces meaning. Her reconceptualization of the idea of ‘home’, as a source of identity in its becoming a boundary event, moreover facilitated a further entry point into the acknowledgement of in-betweenness that arises in any given encounter.10

For water to flow in a river it presumes the active presence (even if they have gone unnoticed) of opposing river banks, which enable it to pick up speed and get into motion. The seemingly uncontainable flow is therefore contingent on its banks. In any of the river’s stages of modification or change in profile, all elements are interlocked in mutual dependence and are engaged in a constant state of re-negotiation; hard bedrock also yielding to the constant motion of water. The image of the river banks not being mutually exclusive, then, linked to our state of in-betweenness and drift during these journeys, where feelings of clarity and obscurity were compossible.

Looking at a map of Southeastern Europe it is striking how many of the national borders follow the course of a river. At the time, I was interested in rivers as invisible and politically instrumental borders, especially between the Habsburg and the Ottoman Empires, borders that divide the peninsula even today. Indeed, rivers as liminal, transitional zones where the course of a boundary remains indefinite formed the starting point for this film. To think of a river as a borderscape is to think of nature in its performative role as a limb in culture’s puppet theatre, imposed and directed by ideology.

The plastic, tactile picture one experiences when peering through the lenses of the Kaiser-Panorama is, in reality, the result of a slightly shifted double image. Two offset takes of the same motif are exposed next to each other on a glass support structure and are separated by an empty strip. This literal interval, then, becomes a structural element that enables binocular vision; the interstice being already materially marked on the photographic medium. Three-dimensional illusion presupposes here a (spatially) simultaneous conjoining of two images.

During the process of researching the film, developing the voice-over text and the on-site travels for film and audio recordings, it often felt as if we

has its point of departure in the loss of the audiovisual footage and repeatedly folds back onto this event by addressing notions of disappearance, incertitude and rupture through affective strategies, the second thread attempts to critically re-situate history in the plural to the extent that it adheres to the premise that history is never one’s own, but resides in the way we are implicated in each other’s traumas.2 The film then, one could say, embodies the process of grappling with this dual telling as it attempts to disturb binaries.

were dwelling in and moving through similar interstitial spaces. What does it mean to leave and to return, or to put it otherwise, to constantly depart? In my reading through the different stages of the project, every arrival was contingent upon a departure, one either preceding or following. Anterior and posterior, both before and after, departure was here linked to a cut, a rupture in an ordinary flow of events. Montage, one could say, was literally taking place way before I had the processed analog film on screen; materializing in the encounter of the body with place—in traversing, leaving, returning, repeating.

The sequence from the film shown here demonstrates quite well the initial obstacle that was present before commencing a project that subsequently grew into a leviathan, and at the same time embodies the project’s momentum: that we were telling or visualizing a story that is, from the very beginning, caught up in contradictions and was too complex to navigate through and apprehend. Cathy Caruth resourcefully observes that one should “Permit history to arise where immediate understanding may not”. In her view history can be grasped in the inaccessibility of its occurrence and as a narrative of a belated experience.15

Returning to the Kaiser Panorama, although it was not our intention to search for images of it in Southeastern Europe, nevertheless it happened so that on our last day of what would be the final trip before going into post-production we chanced upon a Kaiser Panorama in operation at the Cinematheque in Belgrade.

The recorded image and audio sequences came to play a decisive role on various levels of signification in Days In Between. The pre-last sequence, in which diverse shots of the Kaiser Panorama, as it transports the images, alternate with recordings of mounted animals staring at the spectator in the Natural History Department of the University of Cluj is programmatic for the whole narrative of the film. A montage that is governed by comparative viewing and cyclicality could expose the manipulative forces of control, subjection and domination. The characteristic sound of the apparatus transporting the images, wholly alienated now, re-materializes as the auditory ‘sync’ backdrop of a boy chopping wood, an otherwise intrinsically ‘documentary’ scene. The film is replete with analogous incongruent juxtapositions on an image-text and an image-sound level. I will return to this sequence later on when I elaborate on the recent iterations of the project where it disconnects, as it were, from the essay film to transform into a standalone entity.

On one of our first travels we were sitting in Orșova, a small town in Romania but just across from Serbia, where the Cerna River meets the Danube. Just below are the Iron Gates, the impressive gorge separating the southern Carpathian Mountains from the foothills of the Balkan Mountains, a region whose settlement dates back to the neolithic period. Close by, the ‘Tabula Traiana’ reminds us of the Roman road built under Traian, accessible only by boat now and half submerged since the early 1970s because of the joint mega-project between Romania and Yugoslavia, the Iron Gate Dam. In the course of its construction the tiny island of Ada Kaleh in the Danube, a Turkish exclave up to 1923 and forgotten, as it were, at the 1878 Congress of Berlin, was flooded and its inhabitants evacuated. This incident prompted me to consider the genealogy of images (mental and physical) that are always already embedded within economies of the visible and the obscure(d). The reverberation of past events on places and materials took on, in the night of September 11, 2011, very tactile dimensions. It also spawned another feedback loop and reminded me of a family story concerning the flooding of another town, Přísečnice in the Czech Republic (or Preßnitz, as my aunt used to tell me) where my grandfather, having left Germany as a child in 1913-14, had attended a music school. These recollections feature in the last part of the film as text fragments, their respective images gone underwater, so to speak.

telling or visualizing a story that is, from the very beginning, caught up in contradictions and was too complex to navigate through and apprehend. Cathy Caruth resourcefully observes that one should “Permit history to arise where immediate understanding may not”. In her view history can be grasped in the inaccessibility of its occurrence and as a narrative of a belated experience.17

To return to the Kaiser-Panorama, although it was not our intention to search for images of it in Southeastern Europe, it nevertheless happened that on the last day of what would be our final trip before going into post-production we chanced upon a Kaiser-Panorama in operation at the Cinematheque in Belgrade. The recorded image and audio sequences came to play a decisive role on various levels of signification in Days In Between. The penultimate sequence, in which diverse shots of the Kaiser-Panorama as it transports the images (ad infinitum) alternate with recordings of mounted animals staring at the spectator in the Natural History Department of the University of Cluj, is symptomatic of the whole narrative of the film. A montage that is governed by comparative viewing and cyclicality could expose the manipulative forces of control, subjection and domination. The characteristic sound of the apparatus transporting the images, wholly alienated now, re-materializes as the auditory ‘sync’ backdrop of a boy chopping wood, an otherwise intrinsically ‘documentary’ scene. The film is replete with analogous incongruent juxtapositions on the level of image-text and of image-sound. I will return to this sequence later on when I elaborate on the recent iterations of the project where it disconnects, as it were, from the essay film to transform into a standalone entity.