Transposition of Place in Spatialized Music

Place transposition in spatialization arrays crosses paths between electroacoustic music and sound art practices. It is something that developed over time. For example, Luc Ferrari's seminal work evoking place, Presque du rien, is not a work of transposition per se. [17] It is, rather, a window onto a place and time that was present in the world at the time of the work's making, and becomes more and more remote with each passing year. A transportation, rather than a transposition, in place. But the place stays eternally frozen through the glass stereo window, before retreating to its thundering evening of internal music in the second movement. It becomes an image of some mysterious, ever transforming village, transposing itself differently onto the internal soundscapes of each passing generation who encounters it.

Then there are wholly phantasmagorical works, like Åke Hodell's Djurgårdsfärjan över floden styx (The Djurgården Ferry over the River Styx), transposing Charon's crows onto the otherwise peaceful crossing from the south of the city of Stockholm to one of its parks by ferry, just as much as the ferry's transmuted horn transposes onto the map of the Mälaren for a listener. [18] Here the transposition, itself, is imaginary – the transposition of a river. There is no spatialization or sonification of data. But it is a transposition, none-the-less, of phantasmagorical creatures and thoughts of death onto the everyday ferry passage.

Transposition of Space onto Objects

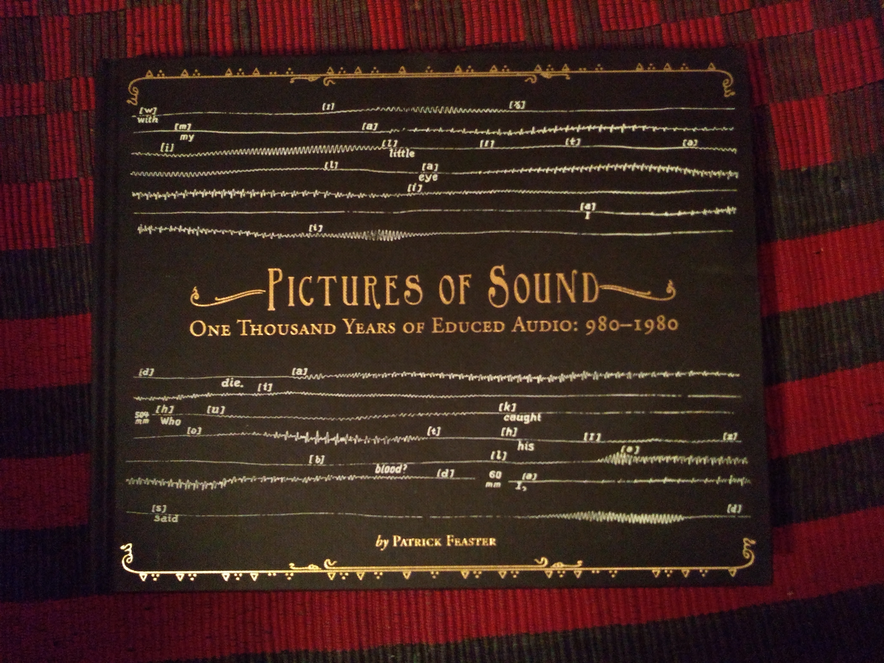

In his unusual book and CD Pictures of Sound, Patrick Feaster writes about the extraction of sound impressions, captured before the dawn of recording, from unusual sources. [6] This unique project features a variety of visual documents and objects used to notate, graph out or otherwise visualize sound, from which hauntingly visceral sonifications are extracted using various methods. There are grainy but comprehensible voices, drawn from the spectrographs of speech made at Bell Labs; eerily human singing pulled back out of spectrographic notation utilized by ethnomusicologists and acousticians; and weirdly lyrical performances of music drawn from mechanical instrument rolls. The sounds and recordings have a deeply haunting quality, as if the entities speaking or singing somehow dwelt in the objects themselves, imprisoned or sleeping for a century or more.

The Landscape Quartet, and most specifically Stefan Östersjö, employ a guitar-based transposition instrument: the Aeolian Guitar. [10, 11]

In their article Patterns of Ecological and Aesthetic Co-evolution: Tree-guitars, River violins and the Ecology of Listening, Östersjö and Bennett Hogg explain the origins of the aeolian guitar performance in their joint project of the creation of sculptural instruments with guitars and violins built into trees:

A guitar is attached to a tree, extra-long strings made from fishing line are fixed to the tuning heads, passed through the bridge, and then extended out into the environment where they are attached to suitably situated trees and tree branches ...Violins, with an extra-long ‘bridge’ made from a hazel stick wedged under the fingerboard, are suspended by this improvised ‘bridge’ from the fishing line, resonating the sounds made by the guitar at the opposite end of the strings ...In solo experiments Bennett discovered that this kind of set-up could also function as an aeolian harp, a discovery which Stefan has subsequently exploited in the development of a unique and identifiable performance technique. [12]

Microphones are placed inside the chambers of the instruments, which are sometimes wholly deconstructed, as described above. But the instruments can also sound on their own. The wind blows against these elongated strings, and they sing, like a chorus; this is what is called an "aeolian harp". The result is a more complex soundscape transposition of the landscape than Lamb’s austere recordings of the outback. Östersjö adds this about how the instruments are played:

Just like Hogg's river-violins (which are bowed by the current), aeolian guitar performance situates the performer in an immediate interaction with the affordances of a site. With strings attached to one or more trees, the performer controls pitch through the amount of body weight put into the assemblage of guitar-strings-performer and tree. By controlling the string tension, pitch contours can be shaped, and also the number of strings playing at a given moment. [13]

Thus, this is also a wholly psychogeographical practice, where the site plays the instruments as much as or sometimes more than the performers themselves, intertwining them in a cross-traversal.

Vic Rawlings' work with speakers, electronics and both modified wooden and aluminum cellos also contains this kind of transposition. [3] Sitting beside a rack of up-turned effects pedals with the backs carefully torn off, he takes bits of copper, sometimes formed into forks or globes, and prods the circuits. These signals are sent to an array of speaker-cones cast across the floor, sitting face up, occasionally with bits of metal, stone or coal in them. To this austere territory of weird membranes he adds sounds that are clearly drawn from the same source – but by hands instead of signals. The aluminum cello has extra resonator strings, and a long, metal rod attached to the bridge. Other cellos have other preparations. When he bows this rod, or over-pressures the altered strings, it is a transmutation of the softly abrasive blocks and shimmies of sound emitted from the pedals and speakers. A transpositional object resonator. In both Ulher's and Rawling's work, a carefully balanced music of individual sounds emerges in stark, on-stepping counterpoint. When another musician joins, such as Mike Bullock, who has also created an intricate world of extended sound with bass and electronics, another layer of post-transposition is added. [4] I have been around a great number of musicians working with this kind of object-oriented improvisation, where transposition comes in the form of magnification; the tiniest sounds transposed onto vast sound canvases, the physical details of objects spelled out in singular up-takes of minute detail. A whole spectrum is to be found here, from transposing the scale of the invisible details of objects, to the playing of the tiniest sounds on a musical instrument, transposing those sounds in magnitude to form whole soundscapes of these austere sources.

Perhaps the most well-known work of place transcription in recent years is Jacob Kirkegaard's work at Chernobyl, released on a recording entitled 4 Rooms. [14] Here, room resonance is the illuminator of ghosts, where he takes recordings of the utterly still rooms of several sites in Pripyat that were once gathering points, and plays them back into themselves in recursive recordings, so that the shifting imprint of air and room spectrums yield a sublime howl. [15]

There can also be precise attempts at parallel recreations of realities, utilizing tools like ambisonics whose nature as a medium contains that possibility, as with Natasha Barrett's OSSTS (Oslo Sound Space Transport System), whose real and surreal versions of Oslo are underlaid by a realistic sound-map of the city. [19] Spatialized music can be another method of aural transposition, when it is conceived as one place transposed onto another, like a different or transformed site, or a room of listeners. Spatial gesture, drawn from or re-applied to a transposed place, animates the impossible, lifting compass pointed geography with cloudbursts of the hand. Even the most accurate, ambisonics-based depiction of a given place creates a liminal world for re-imagining, leaving each person who listens to fill in their own narratives.

And of course there are Christina Kubisch's Electrical Walks. [16] Here participants don specially made headphones fitted with equipment to read electro-magnetic fields and convert them to sound. They are then sent to explore the city, walking in three dimensional alter-locales through a shifting, sonic map of the electro-magnetic world

The artists and researchers whose work I have chosen to highlight here utilize transposition with devices ranging from the wholly acoustic to the mechanical to taking up the invisible fields of electro-magnetism that surround us unawares. Even when walking only with a violin, I am often attempting to emulate, physically or conceptually, these other outer-acoustic ways of transposing the objects, places and entities I encounter. Some make their final transposition, to sonic artifacts or music, through the simple transference of a microphone, or even notation, where others require some further form of electronic or studio processing to bring forth the impression they carry. But each illuminates another entity, be it a voice, object, space or place. Each evokes the possibility to light a parallel image in communion through the act of listening, patterned after the fragments at hand. These pursuits of finding the ghosts of transposed sounds in places, or transposing the invisible harmonics of place – the traces of memory or passage – capture the endless spinning into that past that animates still objects and places, in a psychogeographical time-walk through aural re-mappings of space.

Trevor Wishart's Encounters in the Republic of Heaven is a masterful evocation of place, taking the dialects of a region of northern England, pulling forth a disappearing way of life from their voices, spinning a landscape of anecdotes, soundscapes and transformations out of them, and finally arriving at a requiem where they transmute into song. [20]

The work does not utilize any locational field recordings; its depictions of place and location are crafted and built solely from the voices of the people Wishart interviewed (with the exception of a jovial trombone in one man's story). It is through the transformation of the voices, but also through spatialization and spatialized gesture, that a phantom place is recreated. These everyday places in northern England shift and disappear almost like a kind of wind – like those places are doing in real life. It is a place built, or re-imagined, out of voices – unmistakably a place, transposed onto the listening field of those who join the work in listening, through surround arrays or headphones. This even translates to extend into stereo speakers to an extent, because the spatialized gestures are so fundamental to the work.

These works by Ferrari, Hodell, Barrett and Wishart take on the entity of the place they each address in more multifaceted ways than the utilization of a single or literal transposition technique, which might illuminate only the more solitary details of those places. They represent a range of imaginary transpositions, from the most subtle intimation of drawing one into a recorded place, as with Ferrari, to the depiction of a place re-constructed wholly from a portion of its components, as with Wishart. These four works also range a gamut from literally transposing something almost map-like onto a new field, as with Barrett’s work, to mythological transposition through mapping stories or symbols onto real-world sounds, as with Hodell’s. Places are as much defined, and even produced, by their stories as by their artifacts. Often those stories are as complex, and contain conflict even as they inhabit the same site. So the transposition of place has dimensions beyond the simple act of illumination. Each of these works goes beyond the simple act of illuminating another entity. Alongside the earlier examples of electromagnetic, room resonance, novel microphone playing or amplification techniques, these four works represent another order of transposition, adding a layer of more subjective illumination which is wholly imaginary or conceptual: the far away sea onto the thundering room, the Styx onto the Mälaren, Oslo onto the openly located "Controller Chair", the Northeast of England onto its own voices.

All the works I have touched upon in this section, and the various ways in which they employ aural transposition or psychogeographical practices, have either led me to practices of aural transposition that were new to me, or deepened my own practices of transposition and sonic psychogeography. I take these artists’ practices into my own, as a basis for broadening my own practice, to listen to the city, to re-imagine it, to seek out community in imagining the disappeared and to seek empowerment in the ephemeral. Field recordings and violin work are transferred through the radio-apparatus of modular synthesis and gesturalized space, or are transmuted in the transposition of places and objects; a handful of ghosts around a city of listeners, re-painting the city in simultaneous realities.

In David Prescott-Steed's Intersections of creative praxis with urban exploration, we join Prescott-Steed’s wanderings in the tunnels under Melbourne. [5] One needn’t be a virtuoso like the individuals described above to practice transposition with an acoustic instrument. Prescott-Steed first takes us on a talking tour of the tunnels. Then he begins an activity very well described by its title: Walking Through a Stormwater Drain While Playing the Violin (1380 Returning Steps) – while sawing away on the open strings of an old junk-shop violin. In his walk, a marvelous thing occurs. The sound of the instrument vibrates copiously off the stone walls of the tunnels, and you can hear where the tunnel narrows or becomes wide again, where the ceilings broaden, how the distance fades, by the spectral information in the ongoing, scratchy drone. Transposition of place by resonance; transposition of traversal by strings.

In the late 1990s, composer and sound artist Alan Lamb set microphones on the telegraph wires spanning the Australian outback, and recorded the wind.7 In 2001 I saw theremin player James Coleman perform with these haunting expanses of sound at the Zeitgeist Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts (in Boston) [8, 9] As his theremin took up the spectral clusters of drones and distant glints, there formed a signal-window from the little shopfront gallery onto a vast desert, keening through that sonic view-finder. A young doctor from the Dominican Republic happened into the gallery that night. He told me that he had only ever listened to Caribbean pop music. But now he returned every week for the next several months, "looking for that sound again". The transposition of place onto objects might have a possessing quality; or perhaps it is only that in feeling those sounds viscerally we see our own memories, or futures we imagined, painting themselves onto the places we inhabit or travel through, calling us into their ephemeral worlds.

Transposition of Sound, Object and Space

Transposition of Concrete Sounds with Acoustic Instruments

In my own practice, I never truly act alone. Everything is done walking in tandem with a phantom lexicon, holding a host of other artists whose work I have either witnessed myself, or been shown by still more other artists. For this reason, it is important to address some of the work of others that walks with me most constantly in my own practice.

Perhaps the most well-known example of modern acoustic instrument transposition comes from Olivier Messiaen's work with bird calls.[1] Just as with the transposition of musical materials, the act of transposing bird song, from simple renditions in folk or traditional music to work in the present day, is certainly nothing new to music. But Messiaen was utilizing a modern, scientific perspective – ornithology – in his work. This is a mark of its place in the modernism of the 20th century, even as he was also rooted in centuries of Parisian Catholic organ practices. And it is where a seminal crossroads forms with this kind of transposition, where it is simultaneously a scientific observation and a musical transformation. The organ tradition Messiaen was an integral part of is one with a rich improvisational side, so sophisticated as to constantly dovetail with a complex, multifaceted compositional practice. So the birds are called into this musical universe, and spin virtuosically out of the instruments, transformed and transubstantiated.

In the worlds of free improvisation I have traversed, complex musics emerge from people who have foundations ranging from conservatory training to autodidactic systems spanning many years and plateaus. There are a few musicians who have taken up the transposition and transformation of electronic sounds on acoustic instruments together with the transformation of objects into counter-instruments. Birgit Ulher merges the trumpet with a host of different speakers, radios, recordings and other resonating objects, some scattered across the floor, some placed in the bell of the instrument, to co-resonate with the transposed static and signals she plays back into them. [2]

Fall of Song by Mike Bullock and Vic Rawlings. CD Cover used with permission from Mike Bullock/Chloé Records.