A new staging of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

The goal of the new interpretations, as mentioned in my introduction to this exposition is to re-set the music from within. The resultant new staging aims to relieve it of some of the cultural layers and rituals that have historically been assigned to its interpretation. I want to bring forward a slightly different story, than told by Beethoven, from within the musical material. In a sense continuing what Theodor W Adorno in a grand manner thought to be the pillars of Beethoven’s music as well as for The Enlightenment as a whole; “Humanity and demythologization.” (Chua 2009, 571-572) Beethoven’s music has become mythologized to such a large extent that it is sometimes difficult to hear the music from under all the meanings that have been attributed to it.

As Daniel Chua writes in his essay ‘Beethoven's other Humanism’: “For Adorno, Beethoven's humanity issues precisely from such a definition: by emancipating music from the cultic functions of the past, the composer mirrors the human who ‘dares to know’. Demythologization is the process that brings the autonomous subject and an autonomous music into recognition as brothers of a new humanity. But ironically, music’s liberation from cult coincides historically with its elevation to the status of cult. Far from secularizing music, demythologization tends to convert the means into an end, turning a religious art into an art religion.” (Chua 2009, 571-572)

Going into the more detailed considerations of interpretation Susan Sontag presents an interesting view in her article mentioned earlier: “Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all”…“The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means”.

A central task for my interpretation is to put on stage a slightly less heroic scene for the ‘liberation of the self’. To bring forward a self that is a bit more hesitatant and wavering in respect to its own position in the world. In doing this I engage with what we might call a metonymic strategy. As I discussed in the introduction the Beethoven piece is interpreted metonymically in the sense of looking for close relationships from within the piece itself. No new outer connotations are established, only associations in the mode of displacement.

Accordingly there is no new music being written, no electronics or any other new material added. I start with the music (sic) – ‘how it goes’, or ‘what makes it tick’ (Kivy 2006, 119) - and break some expectations by opening the (sonata) form and cutting out some shorter and longer parts, that for me stand out as redundant today. Instead the interpretation brings forward certain transitions to heighten other kinds of energies and expectations. In the setting, I am trying to transmit the acute sense that anything can happen, as would be the case when the piece was premiered.

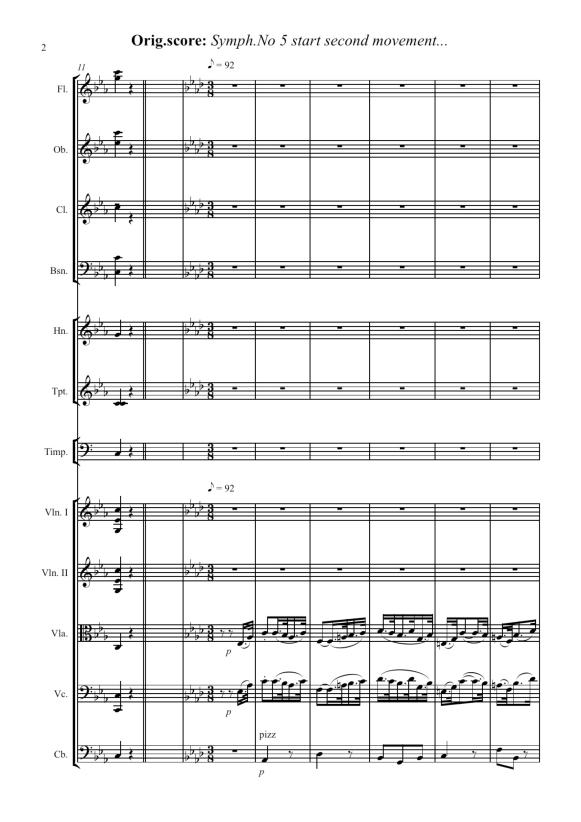

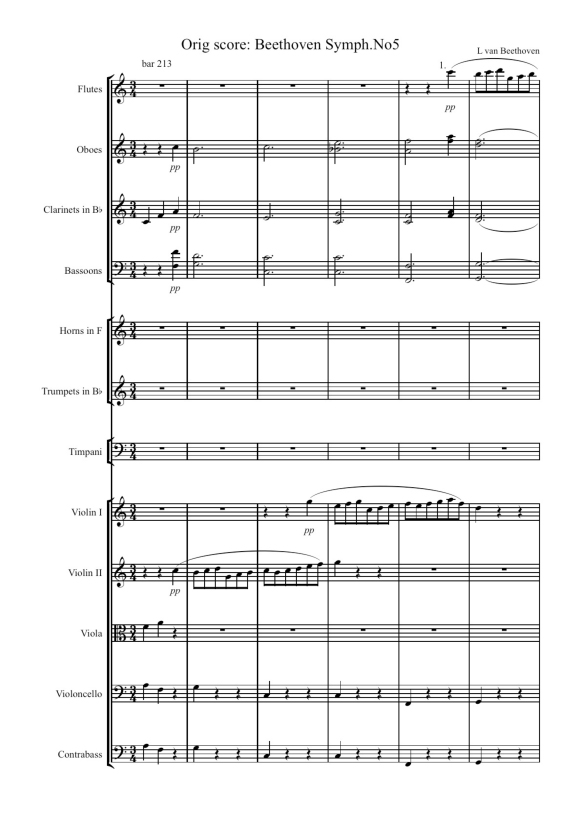

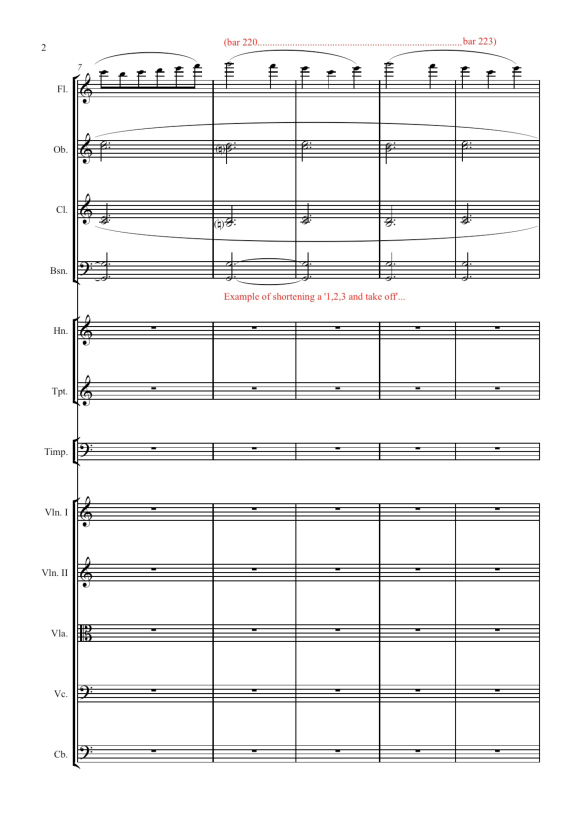

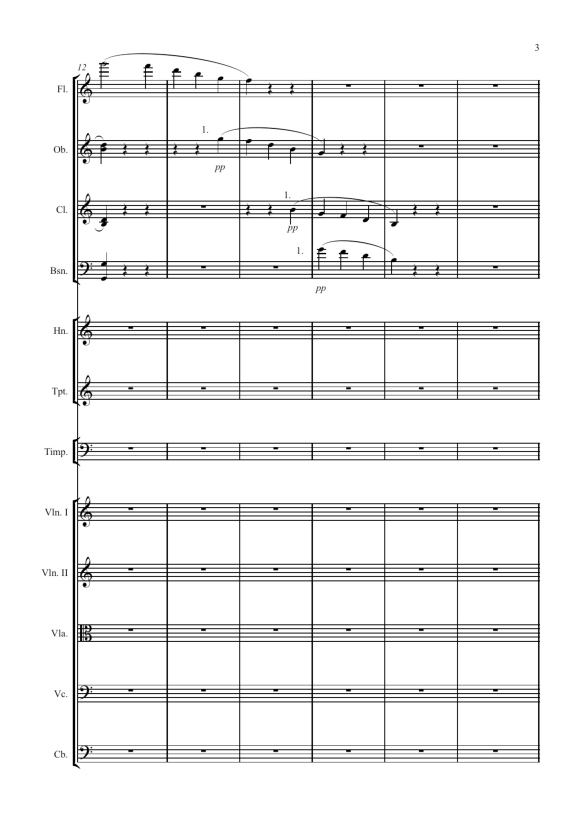

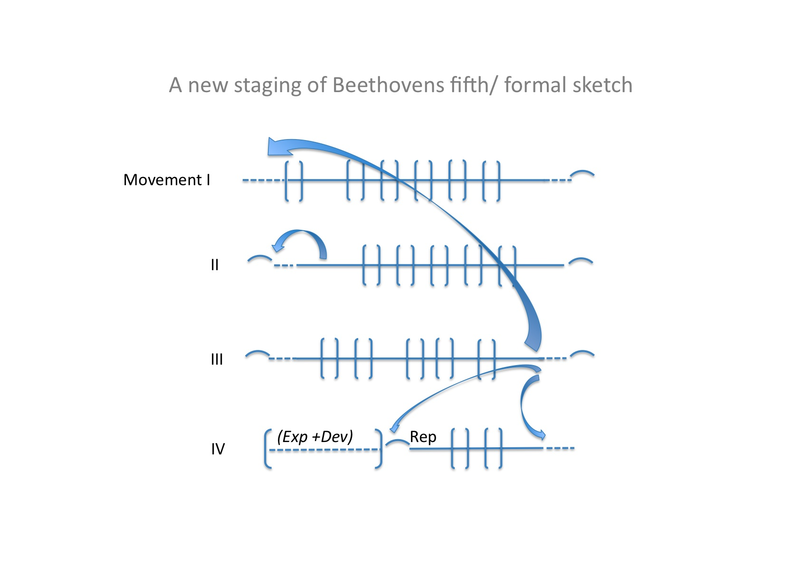

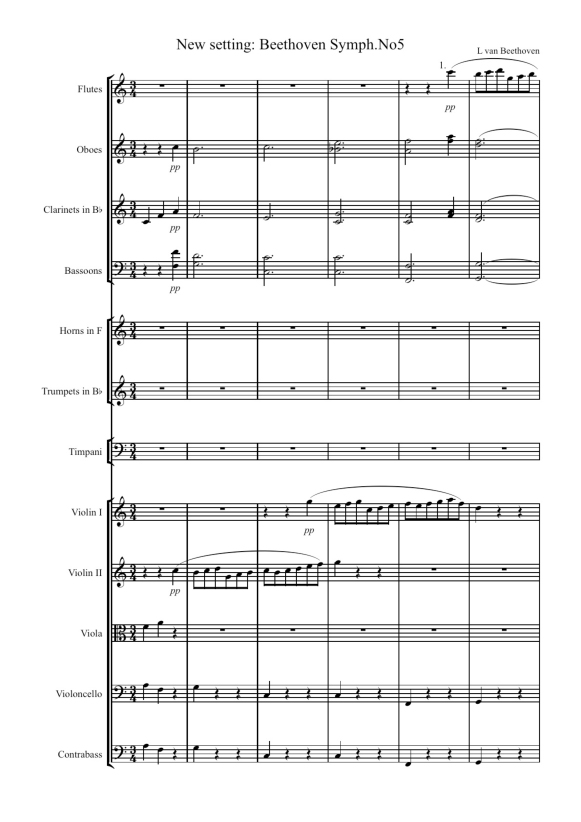

As can be seen in the new version of the score I start by taking the ending of the third movement as an introduction. This then leads right into the ‘ticking’ of the first movement by overriding the first five bars. Throughout the movements, I proceed to scale down some of the time-bound rhetorical ‘set design’ by shortening the number of sequential motifs, taking away repeats and bringing down the number of '1,2,3 and take-off' passages. The second movement starts by bringing forward a passage of sixteen bars starting at bar 49. Further on, the ending of the third movement goes directly to the recapitulation in movement four at bar 153.

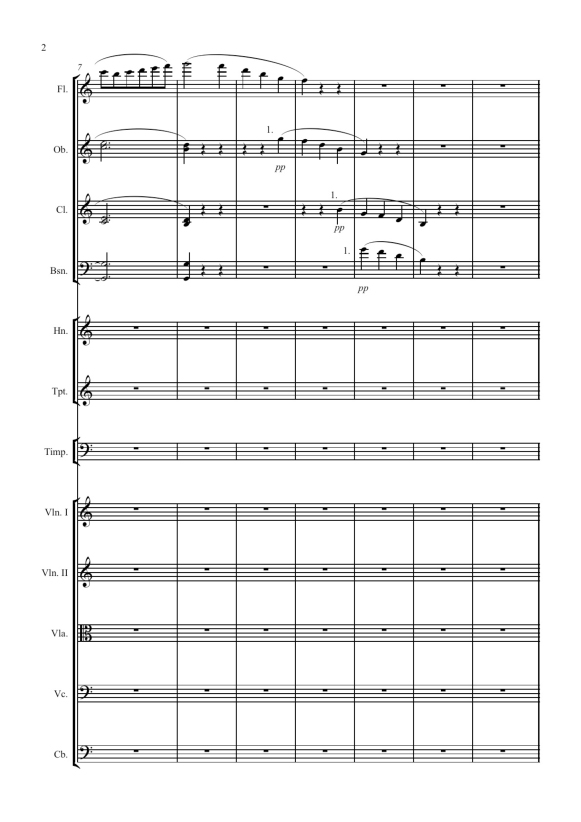

In the musical examples below two of the different operations used in the score are shown. The first one outlines one of the strategies used to bind two movements together and the second one is an example of all the 1,2,3 and take-off's used by Beethoven. Inside the new score there exists a multitude of different minute solutions that will be duly assessed in connection with the rehearsals and performance of the piece.

See fig. 1 for a graphic outline for the new ‘mise en scène’.

(For the non-score reader, sound files are provided. Pasted together from different parts of a recording these are an example of what the traditional and reset interpretations could sound like.)

Throughout the new staging of the Beethovens 5th I bind together all the movements into one continuous flow.

‘One, two, three and take off’ is one of the most frequent rhetorical gestures used during classical times. For Beethoven the gesture at times constitutes the very basis upon which he builds the entire musical phrasing.

In this interpretation of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony I bind all the four movements together into one constant flow. For example, at the very end of the first movement, the clarinet is left hanging in the air in the same way as Beethoven does in bar 268, earlier in the same movement, and where the oboe is suddenly left by itself in a small cadenza. The clarinet leads in to a section, taken from later on in the second movement, which in turn becomes an introduction to the original beginning of this movement.

I’ve always had a problem with the emotional transition from first to second movement. A lot of the energy and compositional tension built up in the first movement gets lost with this ‘180 degrees turn’.

The rhetorical figure ‘1,2,3 and take off’ is used extensively by Beethoven in this symphony. The example in the score is a relatively ‘simple’ one but hints toward the fact that it sometimes can be effective to shorten the ‘1,2,3 and take off’ without losing the meaning of the phrase. It is here used for the purpose of reducing classical balance and getting the course of the music to lean a bit forward.