The Historical Recording and the Film

Approaching a recording environment

As I have discussed earlier, in the still relatively small community of those recreating recordings, there are different “takes” on how to record the recreations. When I recorded my recreated videos, I chose to record them in smaller sections, dividing each piece into parts, sometimes recording a stretch of a minute or two, other times maybe only 20 seconds – depending on the difficulty and complexity of the parts. The value of this was that I was able to have a very detailed focus when imitating the original recordings – which is demonstrated by how my recordings are superimposed onto the originals in the videos. There is however a critique to this approach, considering that Ricardo Viñes and those who recorded some 90 years ago had to do one-off take recordings. There was no chance of editing the finished recorded product and therefore no point in dividing pieces into separate parts (the exemption being classical symphonies or other large scale works that had a duration which exceeded the time limit of the disks). The approach of doing such “one-takes” has an important artistic value because the performer must feel and perform the piece in its full length (like in a concert performance). On the other hand, it is in my view not possible to achieve the level of precision and attention to smaller details which you can get from recording in fractions. Having demonstrated my ability to recreate the historical performances through my superimposed video and sound recordings, I selected five of these pieces and set out to record them in one-takes, approaching a recording environment as similar as possible to what Viñes was exposed to in the 1930s. By recording on the same “terms” as Viñes did, I would be able to reflect on my own experiences from being in that environment, with the positive and negative effects it might have on my performances. As discussed earlier, we know from existing research that the technical limitations of early recordings would occasionally require the musicians to adapt or change their way of playing in order to achieve the desired result in the finished recording. The experiences from this “historical recording” could also provide answers to whether or not Ricardo Viñes might have chosen to exaggerate or alter his performances in the room on the day of the recording.

Recording on a historical instrument with historical equipment was not first and foremost planned with an intention of achieving absolute authenticity, but rather to experience my own playing and sound in the aesthetics of a historical environment. This recording session would also allow for some experimenting with microphone and instrument placement and, through this, adjusting my own playing and performances to the playback. The artistic result of this is the film Playing in the Manner of Ricardo Viñes.

Pandemic delays and difficulties

Although I became very pleased with the final result of the recording project, it was the end of an exhausting two-year long journey of planning, rescheduling and cancellations – a journey during which the project had to change accordingly. The original plan was to go to Emil Berliner Studios in Berlin, Germany to record on a restored Steinway and Sons piano from 1920, through two Reisz-microphones from 1925. The most important reason for going to Emil Berliner Studios, though, was that it would be a “direct to disk” recording. Although the available recording machine itself is 1970s technology, the principle of recording directly onto a lacquer disk is very similar to the 1930s process Ricardo Viñes encountered. The Covid-19 pandemic unfortunately made travelling to Germany impossible, and after several delays, I was forced to cancel the recording and find somewhere to do it in Norway instead. I eventually I landed on doing it at the Ringve Museum in Trondheim, Norway. The aesthetic up-side of this was that the recording room is an authentic-looking furnished living room from the late 1800s with a small C. Bechstein 1916 grand piano in it.[1] The room is part of the guided exhibition and the museum generously allowed us to record and shoot the film in their locations.

Technical equipment

Having been on the search for historically authentic microphones and recording machines, I eventually decided that it might be more practical, as well as closer to the original fully-functioning equipment, to use a vintage replica microphone. With the aid of sound technician Magnus Kofoed, we used the AEA R-44 ribbon microphone, which is an exact replica of the vintage RCA 44BX. The RCA was one of the most commonly-used microphones for music recordings at the time of Viñes, and although I have not been able to find information about the exact recording equipment that was used in his case, it is likely that it would either have been the RCA, or an equivalent ribbon microphone such as the BBC Marconi Type A. The website audiohertz.com has distilled the technical spesifications of the vintage ribbon microphone into these lines:

The first commercially produced ribbon microphone (also known as a velocity microphone) was released in the early 1930s. A ribbon mic works like a dynamic mic except instead of using a moving coil as the transducer, it uses a ribbon. The ribbon picks up sound much like the way your ears do naturally. This is because ribbons are designed similarly to the way your ears pick up sound. Most ribbon microphones are open on both sides, which naturally gives them a figure-8 polar pattern. Interestingly, this made them very popular with the film industry as they could place the camera in the null area of the microphone and minimize the amount of camera noise bleeding through.[2]

Just like in the old days, there was in our setup only this one microphone in use, placed in the room next to the lid of the piano. We experimented with the placement of the microphone in the room and found that this primarily affected the sustain of the sound from the piano as well as its frequency range. The ideal was the recordings of Viñes, and we eventually landed on the location which produced a recorded sound that we deemed to be the most identical to the originals (the placement is as seen in the film). It should also be noted that because this is a recording through a single ribbon microphone, the sound is mono – not stereo.

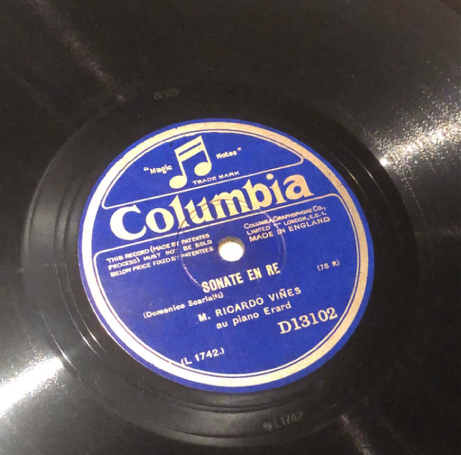

Owning a C. Bechstein from 1879 myself, I am acquainted with historical Bechstein pianos. The one at Ringve Museum is, in the context of how Viñes recorded, probably smaller in size and with both mechanical as well as sound producing limitations due to its age (it is not fully restored). Keeping the instrument in tune was also challenging. Although the piano is kept in functioning condition for the use of performing guides at the museum, it is never used for long and virtuosic recording sessions such as I intended to use it. However, the acoustics of the piano were surprisingly good considering its condition, and it certainly added a feeling of authenticity with its warm and slightly mellow sound. We can only speculate on the brand and the condition of the piano used by Viñes in 1929 and the 1930s, but a 78 rpm recording from the 1930s of Viñes playing the Scarlatti Sonata, that I acquired from eBay, clearly states “Erard piano” on its label:

(My photo of the record I bought from eBay)

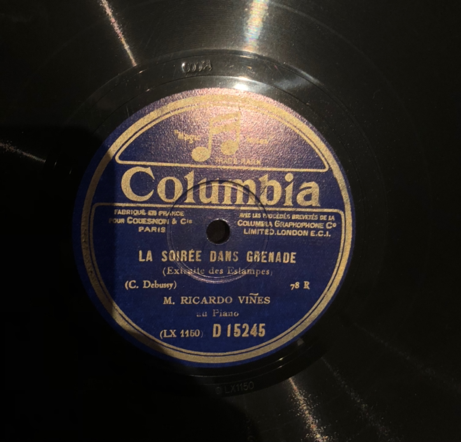

A similar record from the same time of Debussy's La soirée dans Grenade however, simply states “on piano”:

(My photo of the record I bought from eBay)

Being quite intimately familiar with these recordings now, I felt that the pianos on both records sound very alike. It is therefore possible that they were both recorded on an Erard piano, or that neither of them were. The Erard labelling could be there for advertising reasons. The most important factor for me was that what I heard in the playback should be as aesthetically close to the originals as possible – and I must say I was very positively surprised by the similarities in the final result. I do not consider a period instrument to be of vital importance in my project in general, nor in this “historical recording” setting in particular. Although there has been development in the world of making pianos, a modern-day grand piano is still not technically very different from a modern grand a lá 1930. I thus do not believe that using a contemporary modern grand would have drastically altered the results in this “historical recording”; I judge the microphone to be of greater importance here. Nevertheless, I always find myself adjusting to the sound, acoustics and action of any piano in any setting – and the use of an historical instrument certainly influenced the recording in this way. With the exception of the Sanromá recreated recordings, which were recorded on my own restored C. Bechstein grand at home, all other recreated videos were recorded on a modern Steinway and Sons piano (only two years old at the time I started playing it in my office). Having done the recordings at Ringve Museum on an unrestored historical instrument, I became able to compare my experiences on three different instruments – historical, restored historical, as well as modern. My argument remains that although different instruments will produce different results, it is fully possible to thoroughly recreate and perform the fundamental aspects of the historical recordings that I have been studying on any functional contemporary or historic grand piano with 88 keys and two pedals. From a purely aesthetical point of view, I would say that the Steinway in my office had a more precise action and much richer palette of color, sound and timbre, but lacked the warmth and mellow sonority of the Bechstein at Ringve, which in my opinion was more similar to the original recordings from the 1930s.

The sound itself was recorded digitally, with my wife (Rannveig Ryeng) as producer in the other room listening to the takes. The idea of recording mechanically "directly to disk" had to be sacrificed for the reasons mentioned earlier. Although the technical possibility of doing shorter takes and editing them together was present from a practical point of view, we instead chose a “mock-up” approach where the rule was that I had to do one-takes takes just like Viñes, with the aim of staying true to the same “rules” that applied to him.

The film crew from Valkyrien Production consisted of two camera-men. They used modern film equipment, but with the aesthetics of a 1930s film in mind – approaching a filming style with strict and static movements with the cameras on stands, rather than handheld cameras with more dynamic movements which in more in line with modern-day trends. The lighting was also made with modern equipment, but once more with the lighting from 1930s films as an ideal. The film was graded in black and white in post-production and the recorded piano sound from the cameras was replaced by the sound from the AEA R-44 ribbon microphone.

The experience

I went into the project with many expectations. Having already worked extremely thoroughly on the recreations of the historical recordings, I was both excited and anxious to experience how it would feel playing them from beginning to end without stops in a challenging recording environment. Realistically, I was prepared to sacrifice some of the attention to smaller details that I had when working in fragments, in favor of a more overall musical focus. I wanted the recordings to be as similar as possible to the originals, but I also wanted to be able to “set them free”, at least within the framework of something I believe Viñes might have done. To put it simply: if Ricardo Viñes recorded on a Monday, the goal was that my recording at Ringve Museum would hint at how the piece might have sounded had Viñes recorded it once more on the following Tuesday. By allowing this element of artistic freedom within the “Viñes playing style”, I thought the recording sessions would be less stressful than the piece-by-piece -recordings I had already done. I also thought that accepting my own mistakes would be easier in a recording environment that “allowed” for imperfections. I was wrong.

The recording session lasted three days. The following five pieces were recorded:

- Domenico Scarlatti, Piano Sonata in D Major, K. 29

- Isaac Albéniz, Suite Española No. 1, Op. 47, Granada

- Isaac Albéniz, Dos Danzas Españolas / 2 Morceaux Caracteristiques, Tango in A Minor, Op. 164

- Claude Debussy, Estampes, La Soirée dans Grenade

- Claude Debussy, Images 2e série: Poissons d’Or

On the first day of recording we experimented with the distance between the microphone and the piano. The practical advantage of working with a vintage mono microphone is that what you hear is what you get – it does not need to be balanced with other microphones in the room. It did not take very long to find a position in the room where the microphone would record in a similar manner as compared to the original recordings. Myself, the producer (Rannveig Ryeng), and the sound technician (Magnus Kofoed), were all quite surprised by how close we got to the real thing.

In comparison to older historical recording “set-ups” such as those explored in the aforementioned project The Art and Science of Acoustic Recording: Re-enacting Arthur Nikisch and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s landmark 1913 recording of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, as carried out by Amy Blier-Carruthers, Aleks Kolkowski, and Duncan Miller, it is quite clear that our set-up was far less complicated and required less experimentation.[3] However, had we used a “direct to disk” set-up with equipment from the 1930s, we would probably have had to spend much more time than we did. When I recreated the 11 different historical recordings on the modern Steinway and Sons grand in my office, I relied on what I could extract from the original recordings when imitating the sonority. My understanding of how the pianists used pedaling and articulation came from long periods of experimenting with how I could emulate what I heard in the room and on the piano at hand. Although this in many ways answers how the “Viñes playing style” can be achieved on a modern instrument through a modern recording set-up, it does not necessarily address whether this is the exact way that Ricardo Viñes, Sergei Rachmaninov, Ignacy Friedman or Jesús María Sanromá played at the recording venues in the 1920s-1930s. Having tested the recreated pieces on different modern instruments in different rooms, I came to the conclusion that the ways these pianists achieved their rich sonority through articulation and a wide use of the sustain pedal were universal, pianistically speaking. Additionally, I was quite convinced that their rich sonority, particularly in the case of Viñes, came from a combination of brisk articulation and wide use of the pedals and not from the acoustics in the recording venue (like the acoustics of a grand hall). It was very interesting then, to record these recreated performances on a historical instrument with a single ribbon microphone, and through this to examine if I would need to “adapt” my performances to achieve the same sounding results as I had before. The quick answer to this is that I did not feel the need to adapt in any other way than what every pianist would do when they arrive at a new venue with an unknown piano. As before any live performance, I familiarized myself with the action and acoustics of the instrument. The grand piano was situated in a “natural” way in the room and the only difference between the recording and a live performance was the single microphone as well as the cameras in the room. Thus, I did not perform in any “awkward” or different kind of way then I would normally do. As already mentioned, we did some test recordings in the beginning to figure out how far away from the piano the microphone should stand. The various takes were not dramatically different in terms of the sonority in the room, it was more a question of balancing the register of the piano in a way that resembled the original recordings. The way I played in this “historical recording environment” was in principle the same way I had been practicing and playing these pieces when I recreated them at my office. Looking beyond how pianists generally adapt to different instruments in different venues, this “historical recording” experience supports my claim that the performance practice I imitated in the recreating process, particularly with regards to the production of sonority, is universal, pianistically speaking, and that it is within reason to assume that the historical pianists played in a similar manner at the time of the original recordings. Of course, we cannot and will never know the exact conditions in the original recordings, but the important point here is that although the pianists may have adapted their performances because of technically limiting recording conditions, based on my experience I see no reason why they would have needed to.

Another important critique concerning historical recordings and their value as sources is the assumed “lack of control” or the “nervousness” that might have overshadowed the performance, again caused by the recording conditions. Although I have already argued that I believe these ideas about “lack of control” and “nervousness” more so relate to our lack of aesthetic understanding of what these performances really are, and that such statements say more about our modern-day performance ideals than the artistry of historical performers, it was nevertheless very relevant to put my recreated performances to the test in this “historical recording” setting. Would I be able to accept my own “one-take”-performances as a recorded documentation of the interpretation I was aiming for?

In a live performance setting, nervousness and anxiety is typically (for me at least) mostly felt at the beginning of a piece or a concert. As the piece or concert nears the end, I am usually calmer than at first. In a one-take recording setting, however, this is quite the reverse. If I knew I had a good take, the fear of messing it up became greater the longer into the piece I played. This also became worse the more takes I made, because there is a limit to how many times I can run through a piece before the playing quality starts to suffer. I can only wonder whether these feelings were shared by recording artists in the past. Ricardo Viñes probably had the advantage of being free to create very different performances of each piece in different takes, if he so chose. I, on the other hand, was more tied to the interpretation from the recording I was trying to copy. But also, this time, just as when I previously recorded my recreated performances part by part, I realized that by controlling the performance too much, its overall musical sweep and gesture could suffer, which paradoxically made it seem even more distant from the musicality of Viñes. As discussed in the text concerning the recreated performance of the Scarlatti Sonata, I felt I had to play with “less control.” However, we should clearly distinguish between my idea of control and Viñes’s. Because my musical training is cultivated through “controlled” movement in relation to strict pulse and rhythm, I consequently had to challenge myself into playing “out of control” to achieve the desired results (imitating Viñes). Viñes’s training might have been fundamentally different than mine, and as a result of this, his idea of “control” not at all the same. Regardless, having been practicing the recreated performances of Viñes for such a long time, I did not anticipate that this “lack of control" would be problematic at the Ringve recording session - I had after all been practicing these “un-controlled” performances quite extensively. But lack of control I certainly did feel. I think the desire to rely on control is very natural in a stressful environment such as these one-take recording sessions. This rather constant lack of control I felt, often resulted in wrong notes and in my view unacceptable “deviations” from the original recordings. I had thought it would be easier to accept my own mistakes, as long as they were in line with something Viñes “might have done”, but the perfectionist within me surfaced – and this made the recording even more stressful.

Here is an overview of days spent and which take became the “master take” out of the total number of takes:

Day 1 (July 11, 2021)

- Isaac Albéniz: Granada – Master take 7 of 8 total takes

- Claude Debussy: La soirée dans Grenade – No master take of 5 total takes

- Isaac Albéniz: Tango in A Minor – Master take 13 of 14 total takes

Day 2 (July 12, 2021)

- Claude Debussy: Poissons d'or - Master take 11 of 14 total takes

- Claude Debussy: La soirée dans Grenade – Master take 2 of 10 total takes

Day 3 (July 13, 2021)

- Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in D Major – Master take 11 of 18 total takes

On the first day, I made 5 recordings of La soirée dans Grenade, but decided to finish this on the next day. With the exception of this piece, we can see from the “master takes” (which are the ones seen in the film) that I tended to peak in my performances towards the end of the session (at least with regards to the ones I considered to be the best).

Despite the challenges I had to overcome, I believe that I succeeded with what I was aiming for. Regardless of the, at times, “uncontrolled” and “nervous” playing, I feel that we managed to capture elements of the improvisational spur-of-the-moment feel – the truthfulness – of the originals, and consequently, I appreciate what my recreated performances represent musically and what they mirror. If I am able to accept my recordings in this kind of environment and to appreciate that they are representative of my extensive work on recreating these old recordings, I think we could allow ourselves to believe that Ricardo Viñes's recordings are indeed representative of his live performances and could therefore be considered as valid sources.

The film

From early on in the development of this research project, I had a sort of artistic film in mind – something that might express some of the fundamental aspects of my project, not only for my peers, but hopefully also at some level for anyone watching it. Since I was a child I’ve always had an amateur but keen interest in film production. I started making animation videos and worked with film editing software from the age of about ten. This has not only enabled me to do the needed editing and synchronization work on all my recreated videos in this project myself, but to some degree I have also been able to visualize parts of the final film in my head – thinking about camera angles, color grading, the pace of editing and so on. I still wanted a professional film production company to put their touch on this though, because my abilities do fall short of a professionally produced film – a film that could potentially be shown at a film festival for example. I chose the Trondheim based Valkyrien Production. They were very positive and willing to take this big project on short notice - something I am very grateful for. An important point to make in this matter is that my role in the production of this film also includes being something along the lines of a “producer-director”. I have been thoroughly communicating my artistic vision for the film with Valkyrien Productions, both before filming began and in post-production - having an ongoing dialogue with the editor and making revisions and alterations on the way to the finished film. The symbolism of the mustache, the shaving scene, the black and white color grading, the use of the Viñes radio speech interview – all of these were my ideas and visions and the final product is therefore something I consider with a feeling of artistic ownership.

Noise

When listening to historical recordings, particularly those made prior to World War II and earlier, the most immediate thing that comes into mind is the noise. The scientific reasons for this are many, and although I don’t dive into the specifics of this extensive subject in this text, there are indeed others who do, for example Roger Beardsley in the text regarding transfers from 78rpm discs, as well as the 1931/1932 article concerning defects in gramophone records, both found on the CHARM website.[4][5] The most important thing to consider with regards to the recording I made at Ringve is that most of the noise we hear in the original Viñes recordings is “surface noise”, meaning that it comes from the manufactured records themselves. It may be surprising to many, but the “un-touched” recorded sound that came directly from the microphone in the 1930s was probably not very different from what I could hear in the playback from our digital recording at Ringve. Adding a noise-effect to the recordings in post-production was not something I initially planned on doing. Because this noise did not occur in the original recording studio itself, it is in my view therefore not directly linked to the nature of the recorded performance and its natural aesthetics. However, we should acknowledge that this “clean” microphone sound was heard only by the sound technicians in real-time. Once the performance was on the record, the only playback possible was from the disk (which meant some degree of “surface noise”). One could therefore argue that there is no such thing as a produced recording by Viñes without the noise. It’s rather funny, but because I felt that we came so close to imitating the sound of the original recordings, it was rather strange for me to hear them without the familiar “surface noise”. The sound technician, Magnus Kofoed, sent me some examples of my recordings where he experimented with different types of noise that he had programmed mathematically through the software Python. For me, this became the last piece of the puzzle in the imitation process. My recordings now felt even closer to the originals, not simply because of the noise itself, but because how the entire aesthetics in the sound was effected by this. This is quite subjective of course, but having relied so closely on my ears and instincts for the most part of this project, I didn’t see any reason for not doing the same also this time. For the same reasons, I chose also to not only grade the film itself in black and white during postproduction, but also to add “noise” and “grain”. This gives the film this “analogue” and slightly worn look. Working with film editor Toni Kotka, our goal was to achieve this “authenticity” both in sound and image.

Final thoughts

In the end, I feel that I very much succeeded with what I was aiming for in the film Playing in the Manner of Ricardo Viñes. I believe that the film manages to capture the essence of my research. More importantly perhaps, the film raises some important questions about modern classical performance ideals.

[1] The grand piano was previously owned by Norwegian composer David Monrad Johansen and later belonged to his son Johan Kvandahl.

[2] Audiohertz.com, acccesed on Novemver 5, 2021, https://audiohertz.com/2017/05/18/the-story-of-the-man-behind-the-rca-44-and-77-ribbon-microphone/

[3] Blier-Carruthers; Kolkowski; Duncan 2015

[4] Beardsley, 2009

[5] Owen; Courtney, 1931/1932