Piano Sonata in D Major, K. 29

Domenico Scarlatti

Original recording by Ricardo Viñes:

My recreated performance:

Cross-cut video:

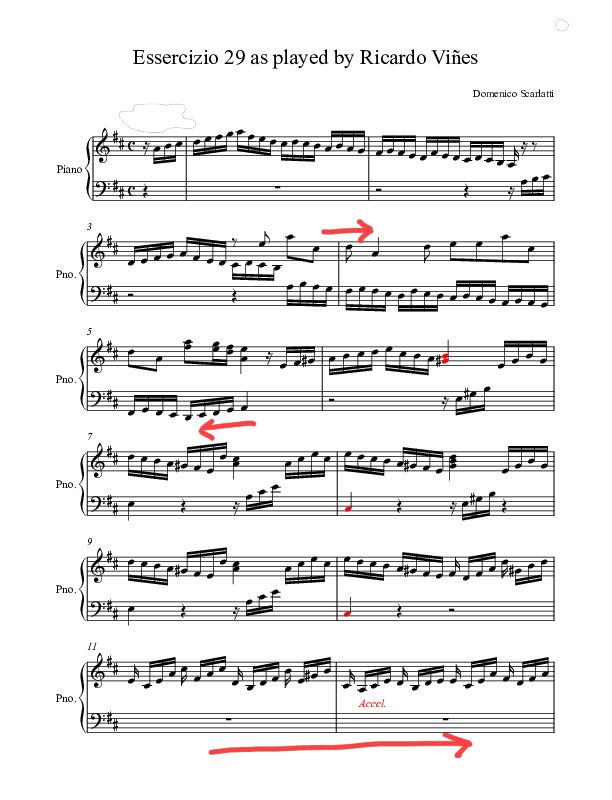

Annotated score:

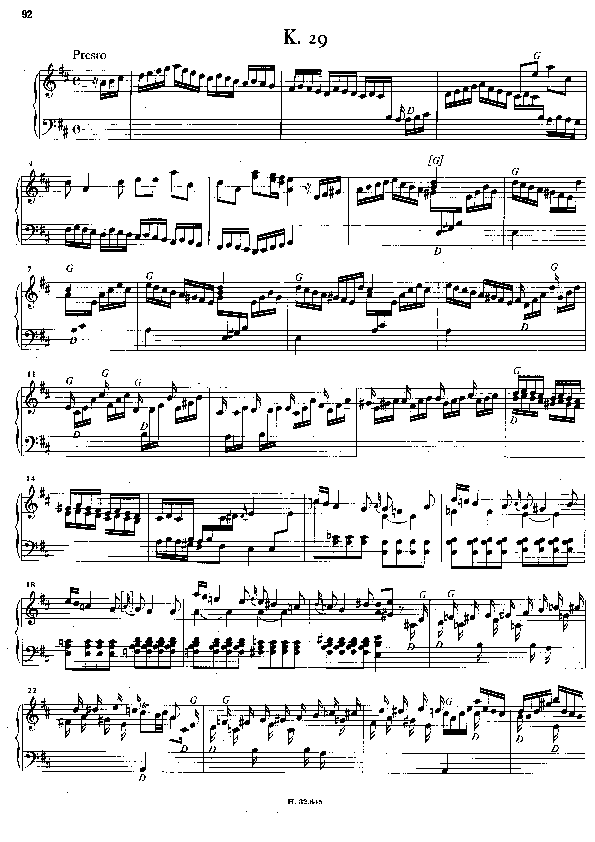

Original score:

The recreating experience

In the contemporary music-dominated catalogue of recordings by Viñes, this is the only piece from a pre-romantic period. In fact, Domenico Scarlatti is the only composer in the list of recordings who died before Viñes was born. Although Viñes was a champion of contemporary pieces, he was also known for his extensive classical repertoire. If the knowledge attained from the romantic performance practice of Viñes could say something about his interpretation of contemporary repertoire in his day - such as the pieces by Debussy - then it would be interesting to also investigate this in a retrospective aspect.

I did have my own ambiguous reasons for wanting to recreate this Scarlatti Sonata because it was initially one of the performances from the Viñes recording catalogue that I found to be the most challenging to “accept,” based on my own preferences at the time. If I was to truly commit myself to the Viñes style of playing, it would be fair to also recreate performances that I found challenging to my own taste, rather than just picking out the performances that I liked. This “gap” between Viñes and myself would in this respect truly test my commitment to this project. It would also be interesting to experience if the recreating process changed my view of Viñes’s performance.

Having already established that Viñes’s recording is very different compared to other Scarlatti interpreters, I still found myself baffled by the amount of deviations between the original score and the performance. The recording of Viñes was so fundamentally different from what I could read in the score that this became one of the most challenging recreating processes of the entire project. I therefore decided in this case to transcribe his performance and make a more thoroughly annotated score. I also chose to divide the characteristic practices of Viñes’s playing into five categories:

- Tempo and rubato (rushing/slowing, “forward-moving” direction)

- “Dislocation” (delayed melody and “polyphonic rubato”)

- Ornamentation (unmarked embellishments such as trills, “octaving”, arpeggios etc.)

- Chord modifications (changing the inversion or adding/replacing notes in a chord)

- Rhythmical modifications (changing the rhythmical structure of the melody)

It should be mentioned at this point that I used an urtext edition[1] when I learned and practiced this piece. My annotated score was made by comparing the Viñes recording to this score. It should also be stated that my annotated score was not made to criticize or correct any existing edition. Rather, it is simply my attempt to demonstrate the deviations Viñes makes from a conventional score that most performers would use today. There are many ways to transcribe his playing and my annotated score is based heavily on my own experience from recreating the piece. Tempo and rubato-practices are marked by thick red lines. Re-arrangements, added or changed notes are red in this score.

With regards to the general tempo and use of rubato in this piece, I found that this was relatable to Viñes’s recording of the Borodin Scherzo. Once more, I was struggling with faithfully imitating the sonority of Viñes’s rapid playing. When I applied “finger legato” to the runs in Viñes’s high tempo, the notes were distinctively clear, but they lacked the “elevated”and light sound of the historical recording. The solution was not to play softer, because then my runs lost the sparkling quality. Once more, the solution was the seemingly paradoxical approach of playing more detaché in collaboration with the pedals to achieve a more forward-moving line. As with the Scherzo, I was forced to “let go” of my control and focus on the greater musical line, rather than on note-by-note precision. I achieved this by once again sitting a little higher on the piano bench and playing lighter in a “semi-staccato” kind of approach. As with the Borodin piece, the sustain pedal in relation to this was the key in achieving the desired sonority. The feeling of “letting go” meant that I constantly had to play on the edge, as if almost losing control. In light of the “modernist” assertion that Viñes plays with little control, as discussed earlier, it is interesting to note that I had the same experiences early in the recreating process. It leads to the question: what is really control? In modern-day musical training, we cultivate “controlled” movement in relation to strict pulse and rhythm, but this may not necessary have been the case with Viñes and his contemporaries. That does not mean he was incapable of playing in a strict rhythm or “metronomically,” but perhaps that the feeling of “control” might be cultivated through different means. Another idea to reflect upon might also be that Viñes was deliberately approaching an “un-controlled” way of playing as a means of serving a higher musical purpose. Although it was challenging to constantly have this feeling of playing “slightly over the top,” I eventually started experiencing the piece in bigger “sweeps.” For the sake of honesty, I never reached a point in my imitated performances of Viñes’s recording where I completely lost the feeling of “uncontrolled” playing, but what changed during the process was that I experienced a greater sense of purpose in his musicality.

The practice of “dislocating” the hands is evident in the four slower sections. As with the previously recreated pieces, the amplification of the melodic material seems to be the reason for this. The right-hand melody has a certain rhythmic individuality and, as with other recreated pieces, the accompaniment follows the melody in a general, but not literal manner (“polyphonic rubato”). Like with the Borodin piece, I found it effective to practice the main theme slowly using a very exaggerated form of “dislocation” to separate the melody from the accompaniment. As I increased to full tempo, I made these “dislocations” gradually subtler. When in full tempo, the practice once again becomes more gestural than clearly audible, but the general sound of my touch had benefitted from this way of practicing.

With regards to the ornamentation, Viñes adds some embellishments throughout the piece. An example of this can be seen in bars 22 and 24, where he adds a chord (A,E,A) that he rolls, probably to embellish the notated trill in the right hand. In bars 28 and 70, he adds a rolled chord to repeat and thus emphasize the last harmony before the next theme. In both first-part endings, Viñes adds notes on all four beats in the left hand and ends up with a low octave before rolling a final chord. In the last bars (89 and 90) he prolongs the entire ending with one and a half bars, making it almost identical to the first ending – another example of the coherency of Viñes’s playing. In bar 85 he adds a third voice to the polyphony by playing two syncopated A natural notes in addition to the D-E-F sharp-E melody in the right hand.

Viñes makes some re-arrangements to the written chords, usually by changing the inversion or the bass note in the left hand (which ultimately also changes the inversion of the chord). We hear this for example in bars 8 and 10, where he plays a C sharp instead of the indicated A natural in the original score. He also changes the chord pattern of the melody in bars 25-28. I suspected this to be a “semi-improvised” way of interpreting the score: Viñes reads a pattern of chords and consequently plays a variation that is not necessarily the exact same as on the score, but in line with the same chord. Ever consistent, Viñes makes sure to do the same thing when the musical material is repeated in bars 67-70. It is impossible to say if this was done impulsively, or if it was a written-out arrangement either by Viñes or someone else. The most important thing is that these re-arrangements are coherent and thus they seem intentional, rather than simply “wrong notes.”

In the four slower middle sections of the piece, there is an extreme use of what I call “chord modifications” as well as “rhythmical modifications.”[2] My transcription might seem a little pedantic, with the use of time signatures such as 9/8, 7/8 and 3/8, but I found this to be necessary because Viñes is dislocating the main rhythm. This can be observed already in bar 15. In the urtext edition, the E natural in the upbeat leads to the C natural on the first beat (downbeat) of the bar at the beginning of this theme. In Viñes’s recording, there is a clear emphasis on the A natural landing on the first beat (downbeat), so that the E, as well as the C and B, is leading to the A, and not the E leading to the C as indicated in the original score. He continues to emphasize this rhythmical structure by accentuating the first of the three chords in each group of the left hand. Indeed, he changes the rhythmical structure in all of the four sections, as I have tried to transcribe in the annotated score. I suspect this “rhythmical dislocation” and restructuring is happening at a gestural level on Viñes’s part - he reads the score in a general way, observing the chordal and melodic material not in a thoroughly literal way as we would do today. If this is indeed the case, we can suspect that he allows himself the use of variations, embellishments and rubato to “semi-improvise” from the score, much like a jazz musician playing from a lead sheet today. It should also be mentioned that it was fashionable at the time of Viñes to publish highly personalized editions and piano adaptations of early works. The transcriptions of 26 Scarlatti Piano Sonatas by fellow pianist and composer Enrique Granados is a good example of this.[3] It is a great shame that Viñes did not record more pieces from the classical or baroque period because it could have been truly fascinating to hear his approach to other composers. I am tempted to suggest that Viñes might have allowed himself a greater sense of musical freedom and improvisation in older repertoires, but it is sadly not possible to put this argument to the test via comparison with other similar pieces. I do however confidently argue that these tendencies are not some whimsical occurrences that simply arose as a result of “nervousness” or a “deteriorated” technique. The coherency that Viñes demonstrates is proof enough to say that his performance seems controlled rather than un-controlled.

Finally, it should also be noted that Viñes does not repeat either of the two main parts of the piece. Based on the limitations in length of these recordings as discussed earlier, it would have been possible to include both repetitions. It was probably rather an artistic choice by Viñes and the recording company.

Comparison to other recordings

In Murray Perahia’s recording, the tempo is faster than with Viñes and very much characterized by a steady pulse.[4] He plays with great clarity and articulation and makes little if any rubato in either of the sections throughout the piece. He also plays both repetitions. There are no “re-arrangements” in the score and I suspect that he was using an urtext edition. Perahia’s emphasis on strict rhythm gives the piece a clear feeling of four beats per bar, which is a contrast to the more rushed and “forward-moving” performance of Viñes.

In Mikhail Pletnev’s recording, there is an evident use of rubato, especially in the slower sections of the piece.[5] His main tempo is generally faster than Viñes, and like Perahia, Pletnev plays very firmly from the fingers with a rather sparse use of the sustain pedal. In the slower sections, though, he uses much more pedal. Although there is much more use of rubato in this recording, the important difference between Pletnev and Viñes is that Pletnev primarily uses rubato to slow down the main tempo. When he is not using it, Pletnev like Perahia also greatly emphasizes the four beats per bar. In Pletnev’s case it is further exaggerated by a heavy use of marcato. Pletnev also plays all repetitions.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s recording is by far the fastest.[6] He plays the first repetition, but leaves out the second. Although Michelangeli’s very strict tempo relates to Perahia’s performance, Michelangeli still manages to make longer lines, not quite so much emphasizing each of the four beats per bar. His slower sections are, like with Perahia, more closely related to the main tempo, and not “slow movements” of a sonata as they could be considered in Pletnev’s performance.

Although these three recordings all have a higher tempo than Viñes’s recording, they all have in common that they are very much “controlled” performances in the sense of a steady pulse that never rushes through musical material. Viñes is consistently rushing throughout the piece, so that the momentum never stops before the end. Where the other performances strive for a crystal-clear articulation, Viñes is making “sweeps” which are further exaggerated by his generous use of the sustain pedal. His pedaling, though, never obscures the melodic material in the slower sections. In my opinion, his use of the sustain pedal in scale runs is an intentional practice that makes the runs sound more “immaterial” – like sweeping waves of vowels rather than well-articulated consonants.

Final thoughts

I would argue that all three recordings used for comparison as well as Viñes’s historical recording display a great sense of “control.” It is instead one's definition of “control” that varies between these pianists' contrasting performance styles and their technical approaches.

It was interesting to experience how my appreciation for the Viñes performance grew as I gradually embodied it. Having recorded my recreated performance in 2018, I left this piece alone until 2021 when I started to re-practice it, leading up to the film recording at Ringve Museum. At this point I had no difficulties in accepting the Viñes performance and it felt natural for me to also play in this manner. Considering this, my view on the Viñes recording had completely changed as a result of the recreating process.

[1] Domenico Scarlatti: Sonates, Volume 1, editor Kenneth Gilbert, Paris: Heugel,1984.

[2] Bars 16-20, 29-33, 58-62 and 71-76 in the annotated score.

[3] Scarlatti, Domenico. Arranged by Granados, E: Veintiséis Sonatas Inéditas para Clave, Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015 (originally published by Sociedad Editorial de Musica)

[4] Scarlatti, Domenico. Piano Sonata in D Major, K. 29. Played by Murray Perahia. Murray Perahia: Murray Perahia Plays Handel & Scarlatti, Sony Classical, 1997. YouTube, accessed on November 2, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fC7wBurIRyQ

[5] Scarlatti, Domenico. Piano Sonata in D Major, K. 29. Played by Mikhail Pletnev. Mikhail Pletnev: Scarlatti: Sonatas Volume II, Erato/Warner Classics, Warner Music UK Ltd, 1995. YouTube, accessed on November 2, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7hqqWz-wufU

[6] Scarlatti, Domenico. Piano Sonata in D Major, K. 29. Played by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli: Piano Maestro, Classical Masters 2009 (originally recorded in 1943). YouTube, accessed on November 2, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMsxNrZQc_8