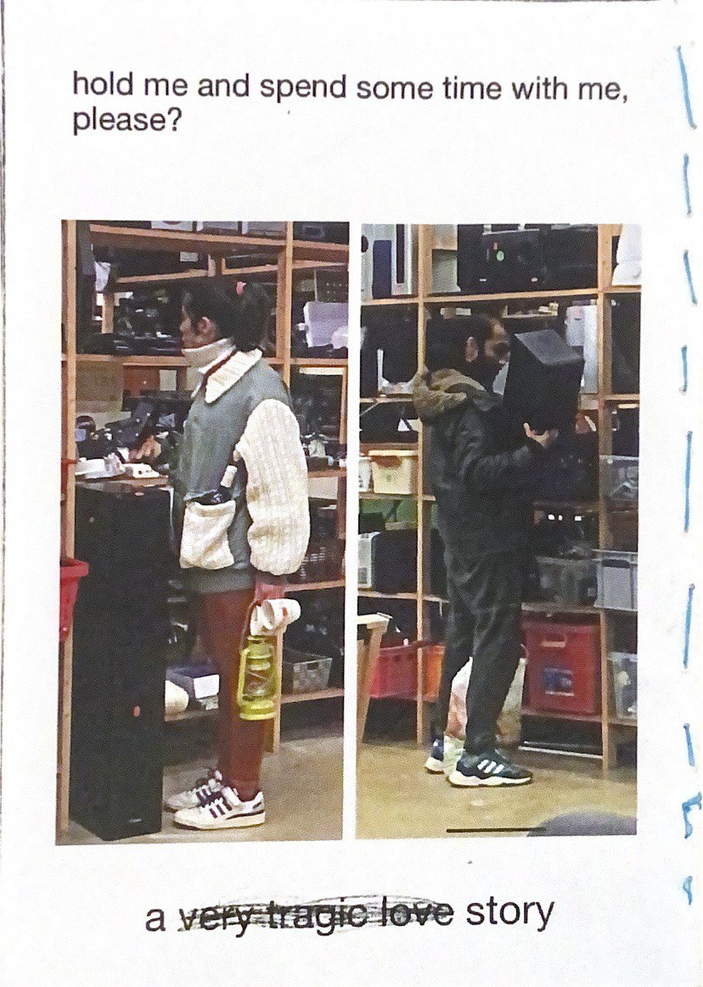

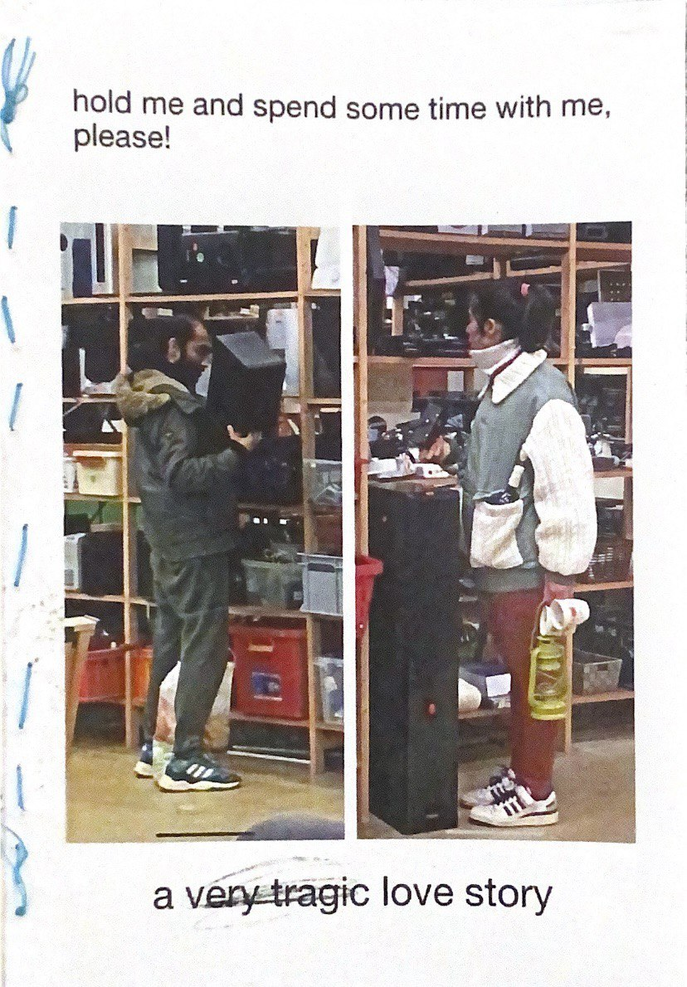

doc presentation in which i explore ways of collective reading and writing

through my own photo collection

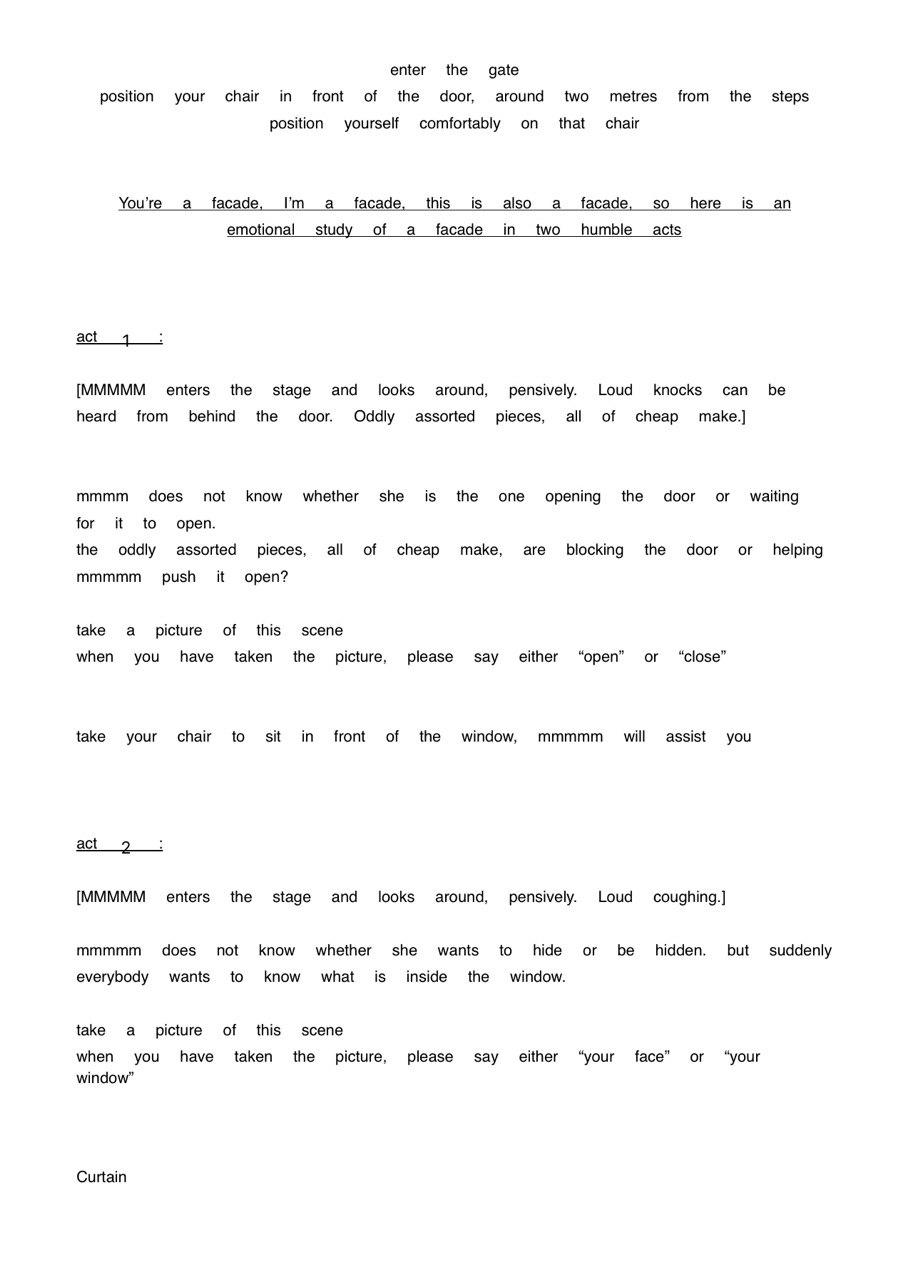

playing around with different textual genres. here I take the play structure in order to both guide and perform

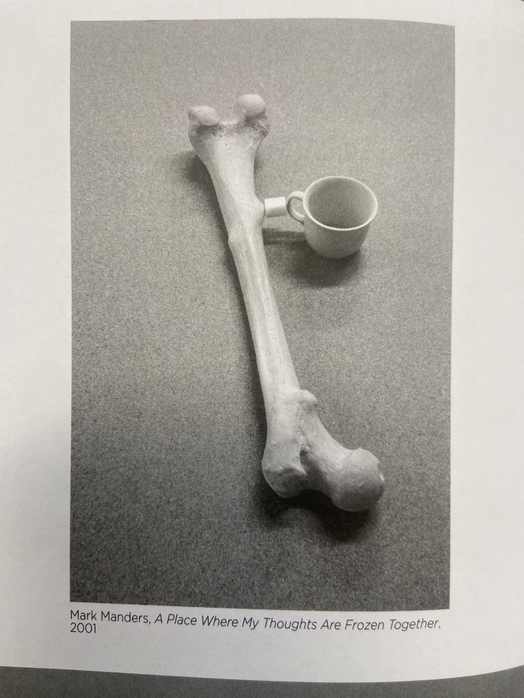

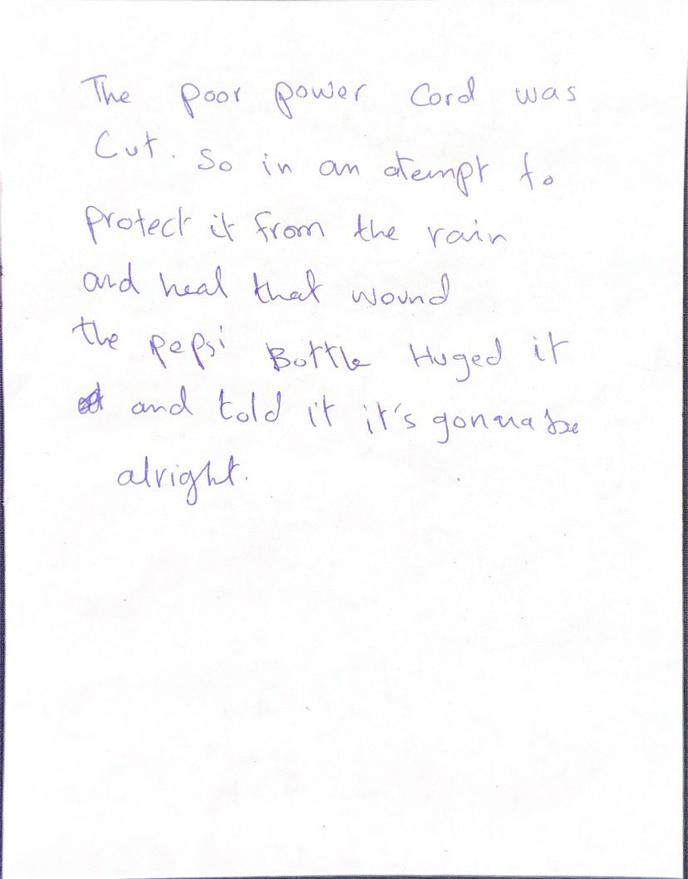

wanting to merge with the object world in times of trouble

bas jan ader

nightfall 1971

bas jan ader

takes place in what appears to be a garage lit by two lightbulbs on the floor. Ader stands behind a large rock. He tries to lift it above his head; he fails and it crushes one of the bulbs. He half-disappears in the darkness. He tries again, and again drops it, crushing the other bulb. The whole process appears as one of self-erasure

Michel Gondry

Interior Design 2008

As Hiroko searches for an apartment in the city, feels hostility from her best-friend for being a free-loader, and figures out a way to get Akira's film reels from her impounded car, (a film which she probably doesn't like) she begins to question what she is doing here. The pop-corn lady at the theater where the film is being screened understands her: it's is very hard being attached to a creative person. You have to subsume your own desires to theirs. And her problem is that she isn't that confident of herself, hasn't found herself or what she is good at.

So in a surreal beautiful sequence she becomes a chair, starts living in another artist's home, invisible but useful, necessary but disposable.

laure prouvost

Seductive, terrifying, provocative, language disobeys, becomes conversely slippery and concrete —> on consumption, death, using sexual bodily linguistic metaphors but also material based destruction such as the melting of plastic, or images of dying bees, etc.

Politics —-

Political Technologies

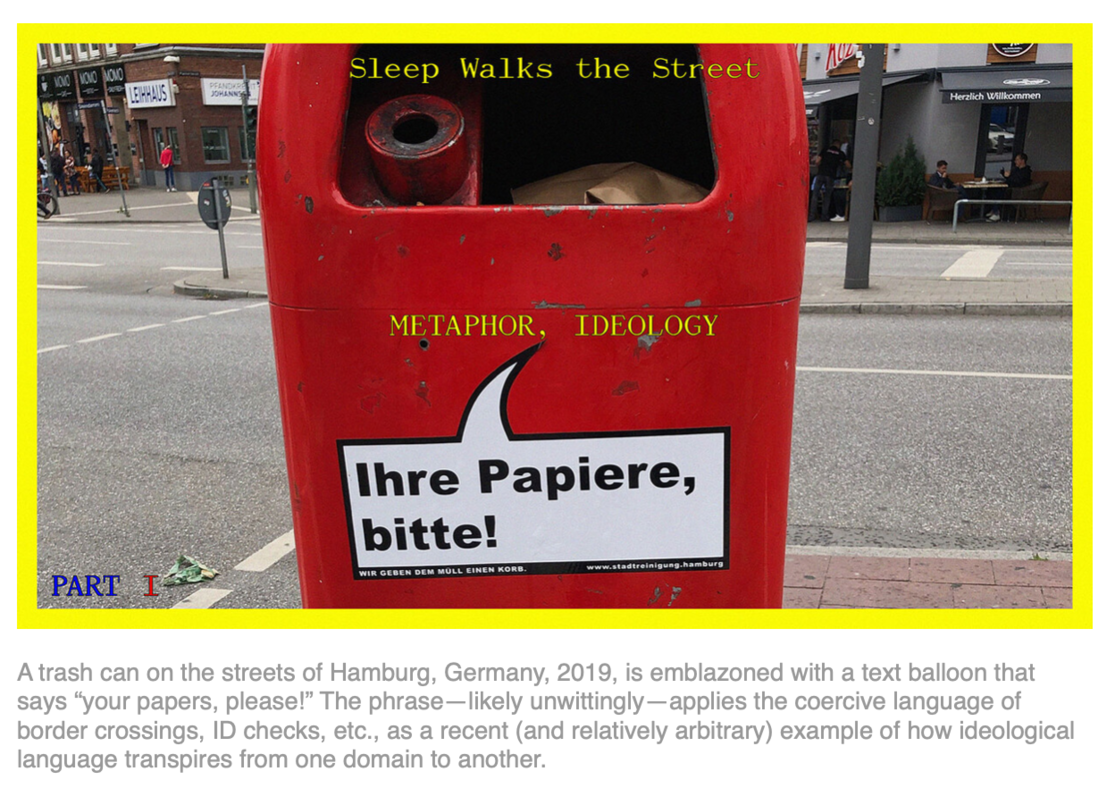

Sleep Walks the Street, Part 1

Metahaven (e-flux)

The cognitive scientist George Lakoff once explained that “the essence of metaphor is understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another.”14 Fredric Jameson has written about allegory in a similar manner, explaining that in it, “the features of a primary narrative are selected … and correlated with features of a second one that then becomes the ‘meaning’ of the first.”15 Indeed, conceptual substitutions of one thing for another thing can overwrite, and thereby erase, the possibility of an encounter with the first. Rather than being instances of clever wordplay to entertain or convince some Greek polis, metaphors, metonyms, and allegories have become scalable political technologies obfuscating, undermining, and instrumentalizing the realities they represent. Of course, the political expedience of metaphors has been well documented. Kateryna Pilyarchuk and Alexander Onysko assert that conceptual metaphors “help [political actors] to both direct and constrain the audience’s understanding by drawing on certain metaphorical themes.”16 Others have noted “the incredible potential of metaphor as a political tool.”17 But all this, while correct, is still understating what such linguistic operations comprise cognitively, and collectively, when supercharged by amplification on digital platforms. Rather than merely shifting a narrative frame, they tend to become the narrative. Some of this belongs to what is now sometimes called “memetic warfare,”18 which, by its very emphasis on “meme,” highlights the amplification and scalability aspects at the cost of taking into account the process of substituting fiction for reality (or of one story for another) that precedes the amplification.

julius koller

Wordplay was a central focus of Koller’s work, in particular the acronym U.F.O., which he adapted in his diagrammatic drawings to stand variously for Univerzálna Futurologická Organizácia (Universal Futurological Organization, 1972–3), Univerzálny Filozoficky Ornament (Universal Philosophical Ornament, 1978) or Underground Fantastic Organization (1975), and which also appeared in a series of slapsticky self-portraits titled ‘U.F.O.–naut’ (1970–2007). These infinite variations on a common cipher constituted an insistent incantation of the Utopian principle. Friedrich Nietzsche argued that to realize a fundamental critique of ‘bad faith’ means to move beyond cynicism and embrace a radical optimism that exceeds the petty dialectics of expectation and disappointment. In his approach to life and art as the U.F.O.–naut, Koller embodied precisely this: he actualized the potential of his imagination as a form of existential agency. As we get entangled in the strange possibilities of art and ideas, we all become U.F.O.–nauts and are deeply indebted to Koller, our patron saint of U.F.O.–nauts.