This work uses artistic research to explore the questions of ethics in the context of transcultural composition. Artistic research is defined by Varto (2018) as a joint enterprise of artistic practice and research methodology, that seeks to generate new knowledge through creative processes. According to the Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research (2020), it is a “practice-based and practice-led research in the arts”.

Coincidently, Lonnert (2015), writing about qualitative research, compares the role of the researcher to that of an artist:

Hence artistic research could be a good way, hopefully, for the readers of this thesis to “live an unlived life”, if not to identify with their actual life if they are composers and do evolve in the realm of hybridity and transculturalism. While the unlived life that I wanted my audience to live on my bachelor concert was that, for example, of a Palestinian civilian, the one that I would like my readers to live through this work is that of a composer who engages with cultures and traditions other that their own, in a context of activism.

Through a research-creation process, I propose to address the research questions outlined above with a critical, reflexive autoethnography approach. In addition, I will use a musical analysis of the work composed, in regards with a workmajor influence on it, and discuss the singularity and originality of the new work, in the context of hybridity and cultural appropriation.

Autoethnography

As Gröndahl (2022) writes about artistic research, “the artistic process can at the same time be the subject, medium and outcome of research”.As a practice-based inquiry, my research relies on a composition work, as well as on the context in which it was realized and later performed. I use both the composition process, the result of that process, the preparation of the performance, the performance itself and maybe reactions to that performance, as well as all the discussions before, during and after the composition process and the performance: my own interrogations and reflections, group discussions within the band, group discussions with friends and colleagues, informal discussions with peers or teachers, etc. In the light of this proposition and within the context of my bachelor project, the methodological framework best suited for this project seems to be reflexive autoethnography.

According to Ellis and Adams (2014), autoethnography is a research method and writing that seeks to link autobiographical stories and personal experiences to the social, cultural and political. They insist on the necessity to be familiar with existing research, which is a critical point in the context of this study where the literature is both extremely profuse, and at the same time quite lacking: try typing “cultural appropriation” in a scholarly literature search engine, you get over 200 000 results, but add the term “transcultural composition” and you get only a couple of results.

Hybridity

Neither the Oxford Music Online nor the Grove Music Online propose an article on the topic of cultural appropriation. However, we can first look at the concept of hybridity, which is discussed and connects to cultural appropriation. According to the Grove Music Online, hybridity is “a concept for describing musical mixtures that are explicitly enmeshed in identity politics, most often involving racial and ethnic identity, and its effects on culture” (Goldschmitt, 2014). The concept seems to have emerged in the late 1980's, early 1990’s in reaction against notions of authenticity and purity in music, and multiculturalism. Especially for diaspora groups, hybridity relates to “the ambiguity of simultaneously feeling connected to more than one place” (Goldschmitt, 2014). However, hybridity was also sometimes criticized over concern of cultural appropriation, for instance in the context of white western producers of electronic dance music using “exotic” samples from non-western traditions.

In contrast, Indian English scholar and critical theorist Homi K. Bhabha discusses in an interview with Rutherford (1990) the possibility of hybridity as a “third space” where different cultures co-exist without a priori hierarchical structures. It is the edge, the liminal space, the in between, “that productive space of the construction of culture as difference, in the spirit of alterity or otherness” (Bhabha, as cited in Rutherford, 1990, p.209). This space allows for the emergence of something new, not less “authentic” than its constituents, and that prefers to ascribe a form of “anteriority” rather than “originality” to the cultures it sprung from (or between).

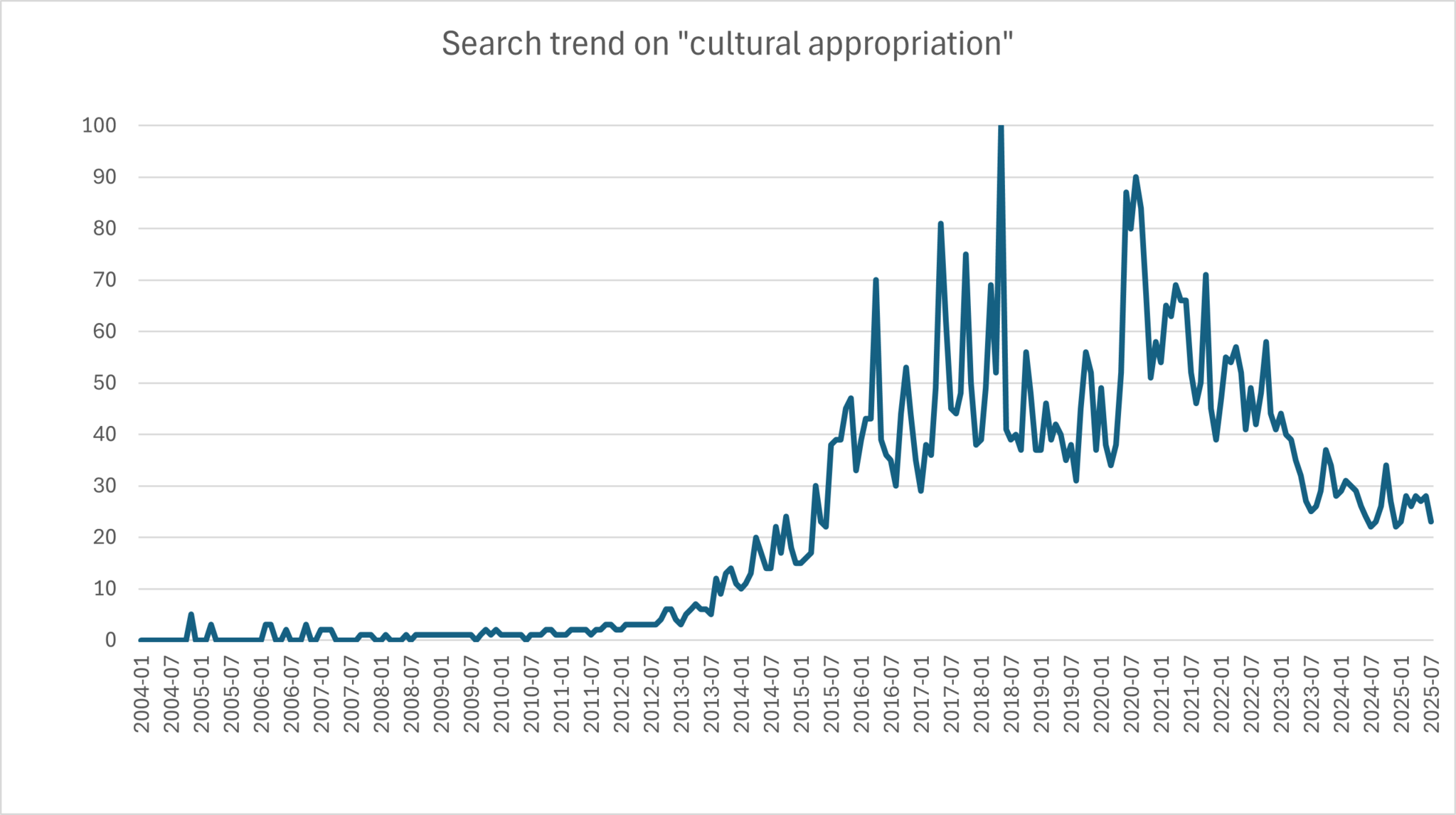

The trend on worldwide searches for the term on a popular search engine gives us an idea of how the interest of the general internet users for the topic have varied over time (Google Trends, n.d.). The chart on the side shows an index related to the number of searches, with an index 100 for the peak of searches attained in May 2018. It shows that the number of searches really starts to raise around 2012. It also shows a general envelope with a peak that has already passed, and we are now on the decline. This would seem to support the idea that the topic is indeed not new, but further than this, that the topic is getting old. Or at least the interest of internet users for it. Of course, that does not mean that the discussion is over, or that we have found all the answers.

On the one hand, certain scholars even argue mostly in favor of cultural appropriation, in defence of artistic freedom. In one of his early papers on the topic, Young (2000) advocates for a largely inoffensive and beneficial use of cultural appropriation. His views are however not necessarily shared by the whole community, and his claims are mostly supported by his own (White Euro-American) intuition, rather than demonstrated properly. One of his favourite phrasing is “I am skeptical about […]”, which he often uses to conclude an argument against the possible harm, or seriousness of the harm caused by cultural appropriation, and declare that (in his view again) cultural appropriation is for instance necessary and beneficial to the evolution of western art music, and such great benefit should not be hindered by the small harm (if any) caused to a few people.

His later and larger work on the same topic (Young, 2008) delves on the same kind of White, Euro-American-centric point of view with little regards to the experience of the indigenous or other people whose culture has been nearly destroyed, forbidden, before being appropriated, despite a foreword where he assures that he has discussed with indigenous people, and that he acknowledges that he lives on their ancestral land, etc.

On the other hand, inspired by Edward Said’s Orientalism, Born and Hesmondhalgh place their discourse around cultural appropriation within the framework of postcolonial analysis: “to examine musical borrowing and appropriation is necessarily to consider relations between culture, power, ethnicity, and class.” (Born & Hesmondhalgh, 2001, p. 3) . The main example of cultural appropriation they bring up is that of African-American musical traditions:

At the heart of debates about cultural identity, property, and belonging in popular music have been controversies over “black musics,” largely because African American music (and other Afro-diasporic forms such as reggae) have been so popular and significant throughout much of the world. […] (Born & Hesmondhalgh, 2001, p. 3)

Do the worldwide popularity and significance of musics of black origin represent a triumph for African American culture? Or a cultural consolation for political suppression and economic inequality? Is the “borrowing” by white musicians of putatively black forms, and the vast profits generated by the recording industry on the basis of such traffic in sounds, merely another form of racist exploitation? The existing debates often take simplistic, polarized forms, reliant on overly bounded notions of the relation of musical form or style to social grouping. Nevertheless, they raise crucial issues about music, identity and difference.” (Born & Hesmondhalgh, 2001, p. 22)

Most of the literature (including the Encyclopaedia Britannica) refers to examples of appropriation by white Euro-American persons of elements of either black, African American cultures, or indigenous peoples like Native Americans. Examples, such as that brought forward in Steven Feld’s A Sweet Lullaby for World Music(2000), are clear cut instances of misappropriation, in general pure theft, and usually involve financial gain for the appropriator.

For some scholars, there exist several forms of appropriation. Thomas Prestø (2025) proposes that not all forms of appropriation are problematic, and that we can distinguish, from those forms that are problematic and generally labelled as cultural theft, between misappropriation, expropriation, and arrogation. Misappropriation is defined as a form of misrepresentation, “in a way that makes it difficult for the originating culture to continue to use the [borrowed] cultural element in its original intent or purpose”. Expropriation is a form of exploitation, defined as taking an artifact or cultural element in order to make it accessible to “others for which it was not intended. Often for commercial use.” In a way that does not benefit (or not mainly) the people with the culture from whom the elements was taken. Arrogation is another form with a less clear definition: “to take, copy, or misrepresent a cultural element or artifact without justification, misrepresented to such a degree that it would not be acknowledged by the criteria of the originating culture.”

Rogers (2006) distinguishes between “exchange, dominance, exploitation, and transculturation” (p.474). For Rogers, the concept itself is undertheorized and the term is often used without enough discussion and framework. Exchange is the ideal case where there is reciprocity and equality between the two (or more) cultures taking elements from each other. Dominance is the case of a minority culture taking elements from a dominant culture, often under the influence of oppression, colonialism, or cultural and media imperialism. Exploitation refers to the reverse case of the dominant culture appropriating elements from a minority or oppressed, or subordinated culture. In that case, which is the one we are most concerned with, Ziff and Rao (1997, p. 9) bring up four different types of concerns: cultural degradation, preservation of cultural elements, deprivation of material advantage, and last the failure to recognize sovereign claims.

However, Rogers warns us against the underlying concepts of sovereignty and ownership, which tend to essentialize cultures and see them as bounded entities. The concept of degradation also points to a concept of subordinated cultures being (or needing to remain) pure, and thus static, denying agency, not unlike how primitivism operates.

Internal colonialism

As mentioned previously, the concept of cultural appropriation has been mostly used in the context of neo- or post-colonialism, whereby a member of a white, dominant group appropriates elements of a BIPOC, subordinated group. However, I think we can also talk about cultural appropriation in a purely white-white context, especially when it comes to the traditional music of certain regions like South-West Occitania in France, subordinated by the central power in Versailles or Paris. Eliza Zingesser documents for instance the French cultural appropriation and gallicisation of Occitan lyrics from the troubadours’ tradition in medieval times (Bolduc, 2021; Zingesser, 2020). By arrogating lyrics and transmitting them in gallicised, French language (langue d’oïl) without crediting properly the lineage, the troubadour origin of the songs are effaced, or associated to unintelligible text, noise, low-register literary forms and “primitive” themes.

According to Alcouffe (2009), the notion of internal colonialism, and maybe the term itself, already appeared in the late 19th century in Spain and East Germany, and appears in France in the second half of the 20th century. In 1966, the politician Michel Rocard, who would become prime minister twenty years later, wrote a report entitled “Decolonising the Province” to the socialist congress of Grenoble (Rocard, 1966). Around the same time, Robert Lafont, one of the founding members of the Institut d’Études Ocitanes, published La Révolution Régionaliste (Lafont, 1967) in which he not only points out how certain French provincial regions are under-developed, but also reads the situation through economic and political processes, to build the concept of colonialism intérieur. He lists five main components of this concept: industrial dispossession and colonizing investment, the importance of extractive industries over transformation ones, dispossession of land for agriculture, dispossession of distribution circuits, and dispossession of touristic resources. For him, these same mechanisms that operate on the economy also operate on the cultural and linguistic sphere. Lafont also proposes a class struggle reading of the situation, and links regionalist claims to anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism and anti-racism (Lafont, 1975).

I am a French-Tunisian musician and physicist. As a musician, I am nowadays mostly interested in musics from various parts of the world, in particular folk and traditional forms, that are often not market-oriented. As a scientist, I specialised in music acoustics, thus linking science and music.

I have not been raised within a particular musical tradition, or then it would be described as vaguely as “western music”, as someone from a non Euro-American perspective could say.

The sound of my family home was sometimes that of western classical music, or The Beatles, as well as popular French singers like Julien Clerc. My own teenage subculture was more that of hip-hop (US and French) and rock (mostly US) at first, as well as the popular commercial dance music from the 90’s (coming almost exclusively from the US at that time), later complemented by reggae (Bob Marley and The Wailers in particular), ska, but also jazz, funk, metal, or electronic music (in particular Jean-Michel Jarre), as well as “chanson française”: Brel, Brassens, as well as more modern bands from the late 90’s and 2000’s of a similar kind. I was hardly rooted in a specific tradition, but rather grew up in a cosmopolitan environment, simultaneously belonging to and building many identities at once, neither belonging here or there in particular, or rather belonging to both here and there at the same time (Appiah, 2019).

As a musician in training, I have first followed a western classical curriculum in my local “conservatoire” (although there was also some occasional and optional jazz and “African percussion” ensemble classes). Despite this environment, I did not grow a love for or a sense of identity within this “classical music”, but the conservatoire was where you could learn music, and I really loved music in general. I dropped out on my last year of conservatoire, not seeing any future for me in that competitive musical and educational tradition, and already starting to play in bands as a drummer (rock, metal, jazz, funk). At the time, I was not in a very close contact with traditional music from any region, whether of France or Tunisia, or elsewhere. But traditional musics where nonetheless always close by, in my hometown: musics from the Maghreb and West Africa in particular, the main regions of origin of the largely immigrated population of this northern suburb of Paris.

Most of the non-western and/or non-classical musical traditions that I got to hear, I encountered later while traveling and meeting foreign musicians, especially during the past decade when I was intensely involved with the “Ethno” series of traditional music exchange summer camps all around the world (Jeunesses Musicales International, 2025). These experiences also made me discover various musical traditions from “my country”, or rather from my countries. It was an opportunity to discover that France is composed of diverse and contrasted entities. Each region has a distinctive musical tradition, and sometimes its own language (rather than a local dialect of French). Similarly, I started to discover the musics of the Arab world, only to realize how rich and diverse those are and that there is not just one “Arabic music”.

These realizations are also connected to my position as a (half) White-European, which sometimes leads me to adopt, by default or by lack of awareness, the dominant’s point of view, although I also belong to (one of) the (many) subordinated people, considering France’s colonial history and its imperialism. This is important for talking about cultural appropriation, because I can be on either side of this power dynamics, and it can be confusing. From the point of view of racism, for instance, I am sometimes seen as a White person, and people can project on me all the prejudice that they have against the White, racist, colonizer. But I am also sometimes viewed as a person of colour (POC), depending on the situation, the place, the people around me. This latter case having been my most common experience as a child and teenager in France, it has been, at times, easy to forget that I am also, partly, the White person, the indirect beneficiary of colonisation and slavery, and a native speaker of a language that was imposed by force on so many people, etc.

Within the French context, I also grew up in the capital region, close to the centres of power, learning the “proper” French, going to elite education institutions, and growing up not knowing that France also contains regions with their own language and culture, regions that have been -or some maybe still are- underprivileged and underdeveloped by the central power, exploited and dispossessed from their local resources, and repressed against the use of their language and the expression of their culture.

This research was conducted following good practices of research integrity with regards to reliability, honesty, respect and accountability, as proposed by the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (ALLEA - All European Academies, 2023), similar to the guidelines promoted by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK, 2023). In addition, the collection, processing and storage of data, especially personal data, follows the EU General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679, 2016), often referred to as GDPR, concerning the use, storage and transfer of personal data.

However, the ethical considerations of this work are somehow intricate because, as an auto-ethnographer, the other subjects of my accounts are easily identifiable. So even when I did not conduct specific interviews, where I would have explained the research goal and received an informed consent, people around me in my daily life are part of the story I write, so there is a balance to find between revealing certain details and preserving the confidentiality and privacy of those around me. As Starfield (2019) writes about autoethnography:

The self that is studied is part of a community of others who will inevitably be described in relation to the self. Consideration should therefore be given to issues of informed consent, protecting anonymity and confidentiality, and other matters that may arise in other strands of ethnographic research. Privacy concerns may be more urgent in autoethnography as the participants may be more easily identifiable due to their closeness to the author of the study. (Starfield, 2019, p. 168)

Here, there is no “one size fits all” recipe on how to tackle this problem, and it is through writing, reflecting, reading, and writing again, that I tried to find this balance. I kept my reporting as vague and anonymous as possible, but I also took the liberty of naming, not people but institutions, to better situate myself and the context of this study. To only one exception, I did not conduct specific interviews on the subject. The reflections mostly come out of informal discussions, an accepted method of qualitative research (Swain, 2022), whether with individuals within my academy, or within groups of practitioners, such as bands with which I have played.