1. Ouverture: La guerre menace (Opening: The threat of war)

I started composing as an exercise of imitation, in search for that energy that San Salvador is able to communicate. Along the way, I naturally started to put more of my own ingredients into the music, but the opening section of Pierrot et La Guerre is maybe the part where the imitation is most recognisable.

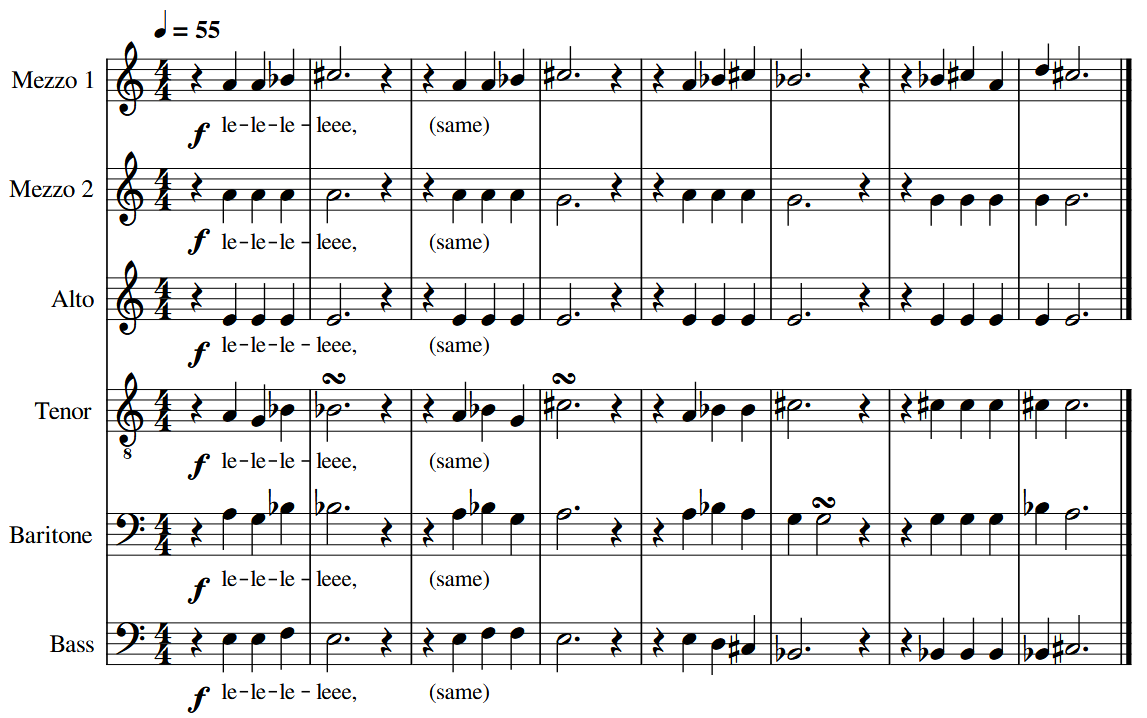

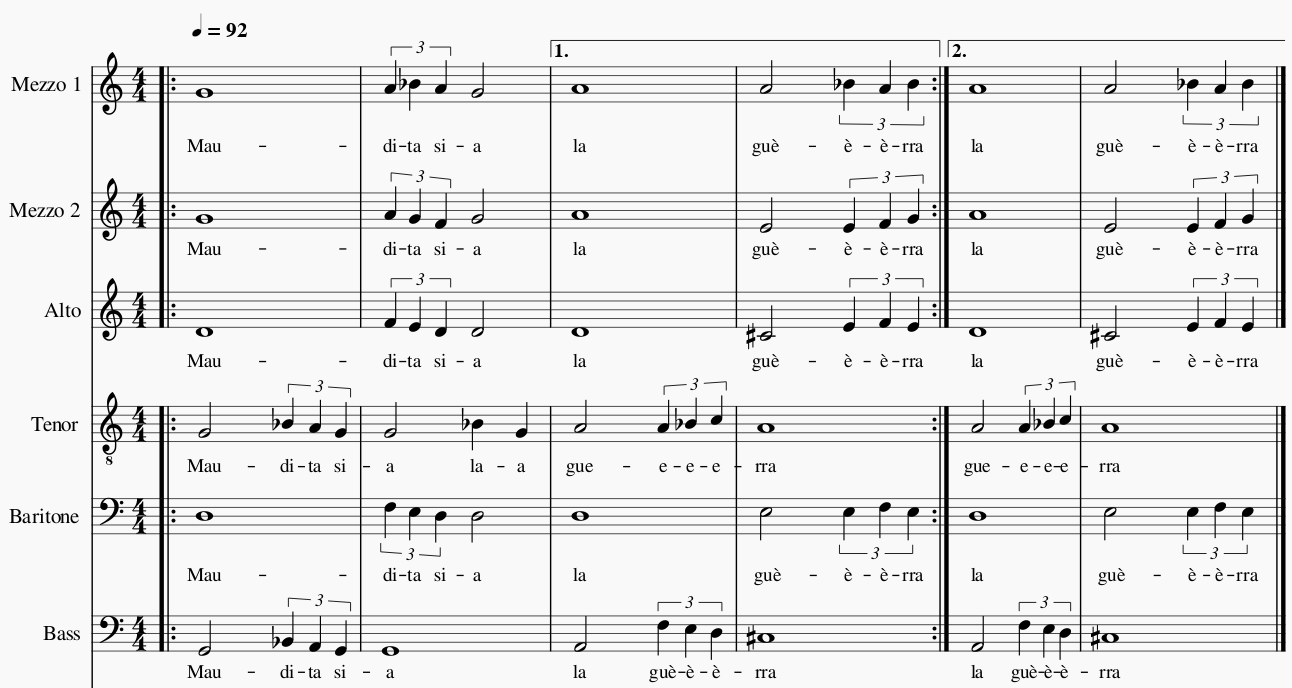

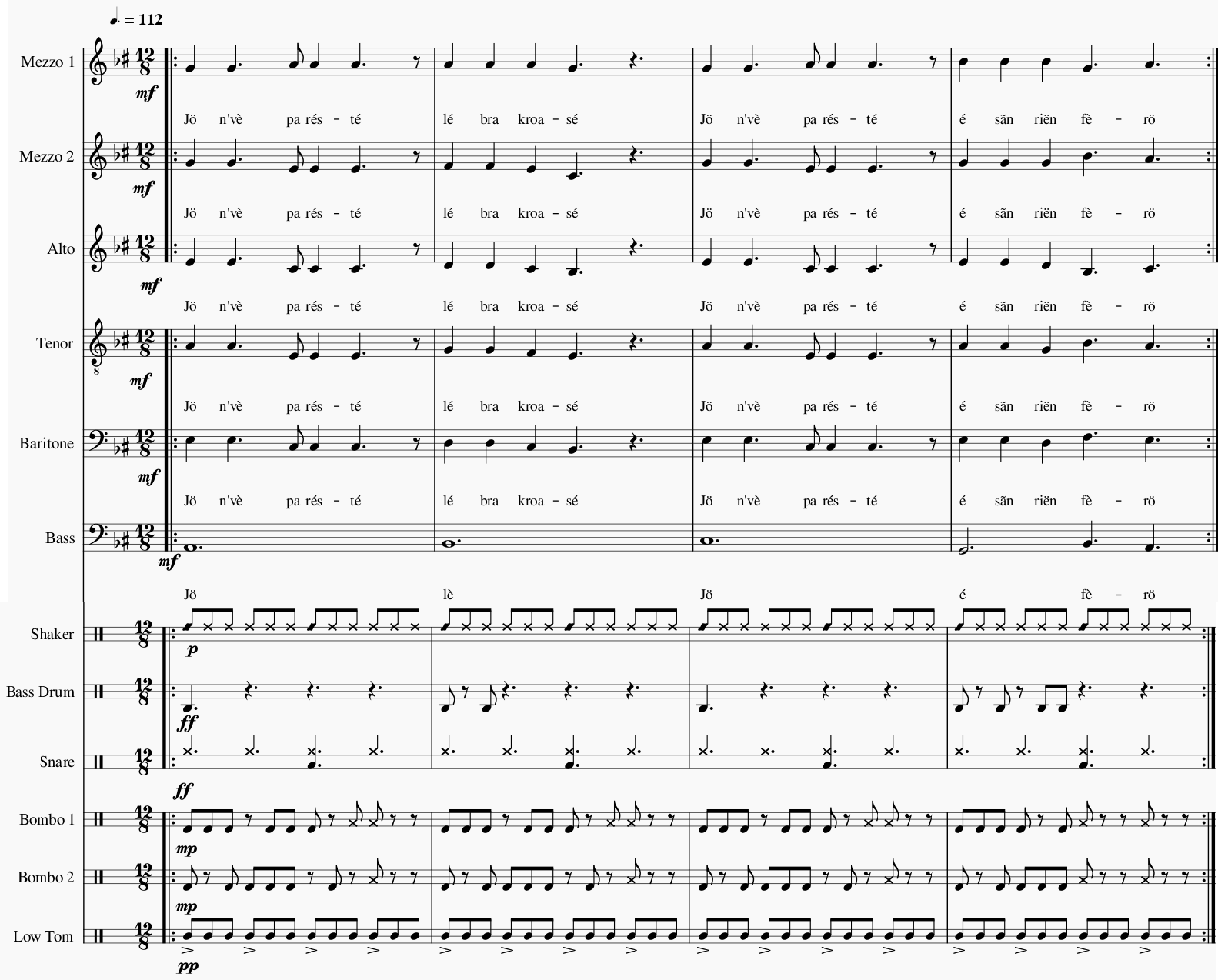

Figure 2 - Score extract of the opening

In this opening, I used a series of four slow and long chords, arranged in four phrases, which repeat as a long loop, adding up a voice layer at each round, with a heavy use of narrow intervals. The two higher voices start together, then adding the Alto voice, then the Tenor and Baritone, ending with the Bass. It is similar to the opening of La Grande Folie with the tempo, the type of voice, the long notes, and the staggered entrance of each vocal part, and the presence of narrow intervals. I also use a simple syllable “lé” instead of actual words. This way I use voice here as an instrument, rather than for its ability to articulate words.

In this section, the two highest voices operate together, with a melody on the Mezzo-Soprano 1 accompanied by a second voice on the Mezzo-Soprano 2 which oscillates between Ist and VIIth degrees, while the Alto sings a pure drone, on the tonic first, and on the dominant later. Similarly, the Tenor and Baritone parts operate together, forming an internal duo, while the Bass sings an accompanying line, although with more movement than the Alto part.

The role of this section is, from the start, to impress the audience with strong voices, lots of dissonances (at least in the western classical view: major and minor seconds, as well as tritones) and to bring up a feeling that something terrible is about to happen. The storyteller has talked first, exposing the situation, so the audience has a bit of context already: Pierrot, the main protagonist, lived happily with his family when rumours of a war with the neighbouring country came in the news. He lives close to the border, and as a pacifist he really does not want a war to brake with his neighbours, with whom he really sees no reason to quarrel.

This part is also a recurrent theme throughout the suite. It comes again in different versions, with different voicings, arrangements, and dynamics, always to remind us of the brutality of war.

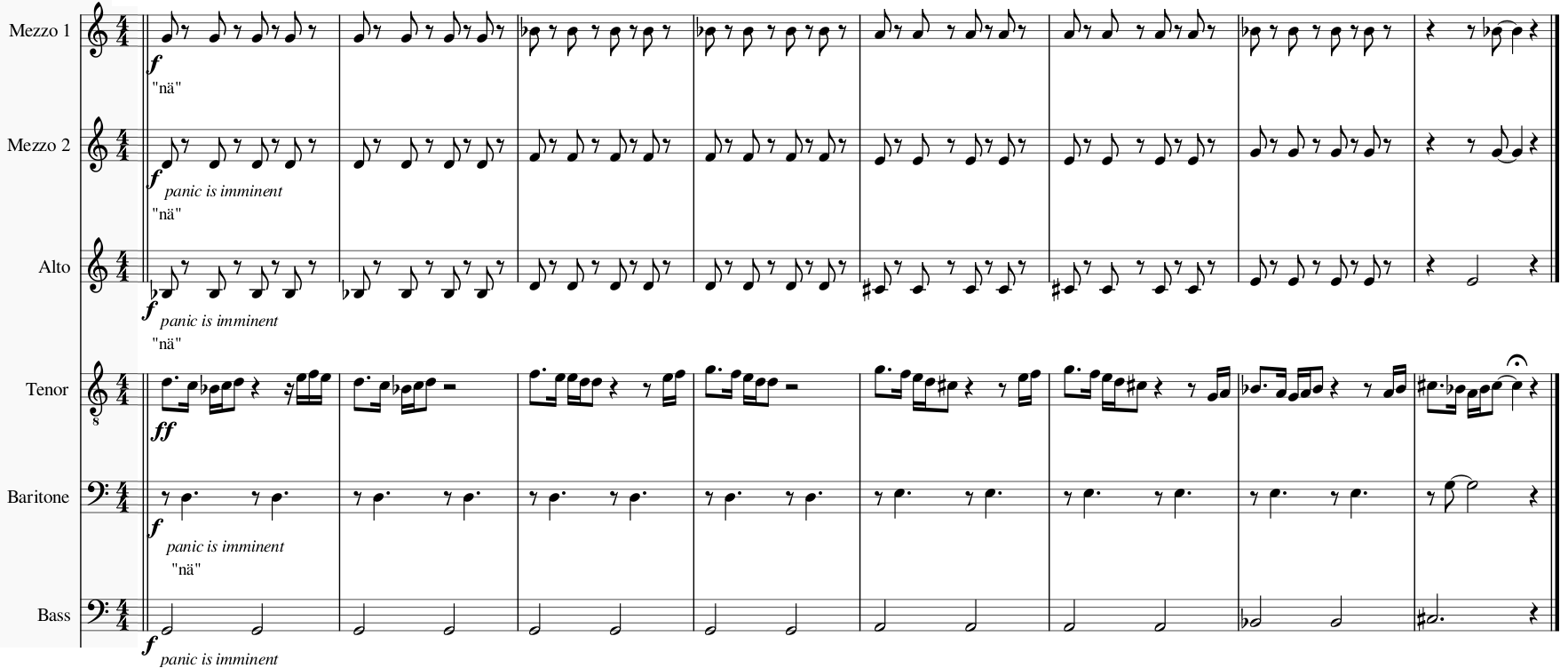

In the second section, the tenor part has a solo melody while the five other singers provide a background accompaniment. The percussion part is relatively light and consists basically in one rhythmic groove in 12/8 distributed over the set of players and their instruments. The entrance of each instrument is staggered in order to fill up the space gradually.

The vocal accompaniment is soft, with mostly simultaneous voice parts arranged in whole note chords. As the music progresses, it slowly turns into ostinatos with more movement in heterophony, where the different vocal parts answer each other with a rhythmic movement in different parts of the loop.

The third section starts in a very similar way, but the rhythm is in 4/4, decidedly binary. The solo melody of the tenor emphasizes this binary nature of the rhythm. The vocal accompaniment leaves a lot of empty spaces, at first, but after a few repeats the voices are getting more insisting and eventually come to a quarter-note rhythm with a more threatening sound, while the solo voice ends up an octave higher and sounds very anxious: the war has been declared and the protagonist, Pierrot, is called to be drafted in the army, which induces anxiety, reaching panic at the end of the section.

The fourth section is a rework of the opening, the recurrent theme. It is a bit shorter, and starts with the three higher voices at once, but the “main melody” that was on the highest voice in the opening transposed down for the Alto. The lower voices are unchanged.

Giving the main melody to the Alto gives an overall lower center of gravity for that part. It “sounds lower” and it can be sung a bit louder too. Also, interestingly, the Alto part endsup really close to the Tenor, bringing friction in a different range than in the opening, and for a longer time, reinforcing the idea of panic because of the imminence of getting enrolled in the army and sent to the frontline.

5. Adiu la bèra Margoton (Farewell, beautiful Margot)

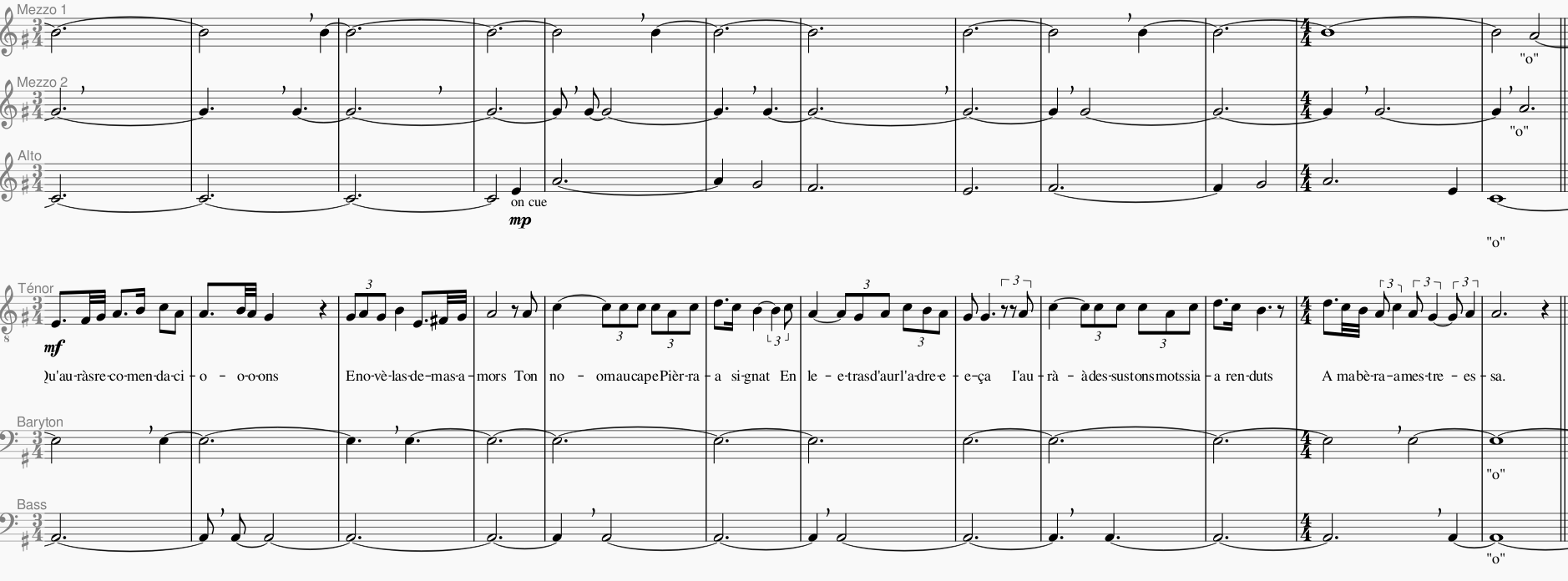

The fifth section of the suite is a rearrangement of the traditional song Adiu La Bèra Margoton (Adiu La Bère Margoton, n.d.), which is part of the repertoire of chant béarnais, an Occitan dialect of the region around Pau in the Pyrénés gasconnes, in the South West of France.

In this ballad-like song, the narrator bids farewell to his loved one, because he is called to serve in the army, for the king of France. My arrangement is inspired from various versions I have heard. Especially that of Las Que Cantan (Las Que Cantan, 2024), in which some voices sing drone parts.

As I arranged it, the song is entirely a cappella, without percussion. Although I listened to various modern versions that included percussions, as I was tempted to add some myself, I was never convinced or inspired by those attempts. The rubato nature of the song does not combine well with a rhythm that has a pulse, in my opinion.

The “normal” voice (one can think of a cantus firmus) is here sung by the Tenor as a solo part, while the other voices accompany with drones, each on one note of a ninth chord. Starting with the Bass only (tonic), the Baritone (fifth) enters in the second verse, and then higher voices (Vth, VIIth and IXth degrees) come in one by one in the third and fourth verses.

In the third verse, the highest voice has a slow movement (between Ist and VIIth degree), and in the fourth verse, the Alto takes on a counterpoint above the main voice, but at a much slower pace, in a sort of faux-bourdon style. Finally, in the last verse, the five singers act as a choir singing fully developed chords on the pivotal points of the melody, following the rhythm imposed by the solo melody of the Tenor.

At the very end, the Tenor and Alto take again the first verse as a duo, the other voices keeping quiet. The main melody, sung by the Alto, is transposed a fourth up and the Tenor sings the second voice that I originally learned for this song, honoring here the vocal tradition of Pyrénées Gascogne.

Note that in a subsequent version, the very first accompanying chord was simplified, and the drones were sung by two voices in unison, in order to use choir breathing and have a more continuous flow of energy in the background. To reinforce even more the feeling of a continuous flow, we added a shruti box1 as a support on the tonic and the dominant. It also helped keep a stable pitch along this long section (about 6 minutes).

1 A compact, hand activated harmonium originating from the Indian subcontinent that allows one to play drones.

6. Le refus - Maudita sia la guèrra (The refusal)

The sixth section starts immediately after and is divided into two halves. In the first one, the text reads “Maudita sia la guèrra” which means “Damned be the war”. This sentence in Occitan is found in the first verse of Adiu la bèra Margoton and it can be thought of as a leitmotiv of the whole suite so far, as it is the only line of text that is sung by all the voice parts. This section possesses the highest intensity, in both voices and percussion, since the beginning of the suite, and brings a sort of climatic moment.

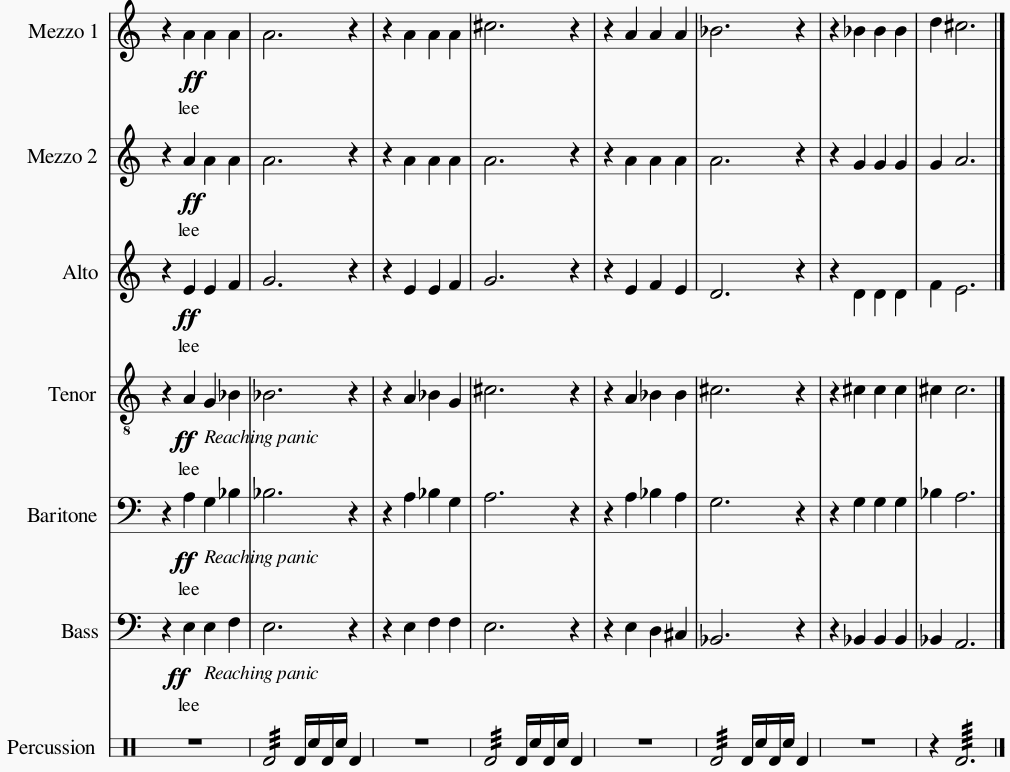

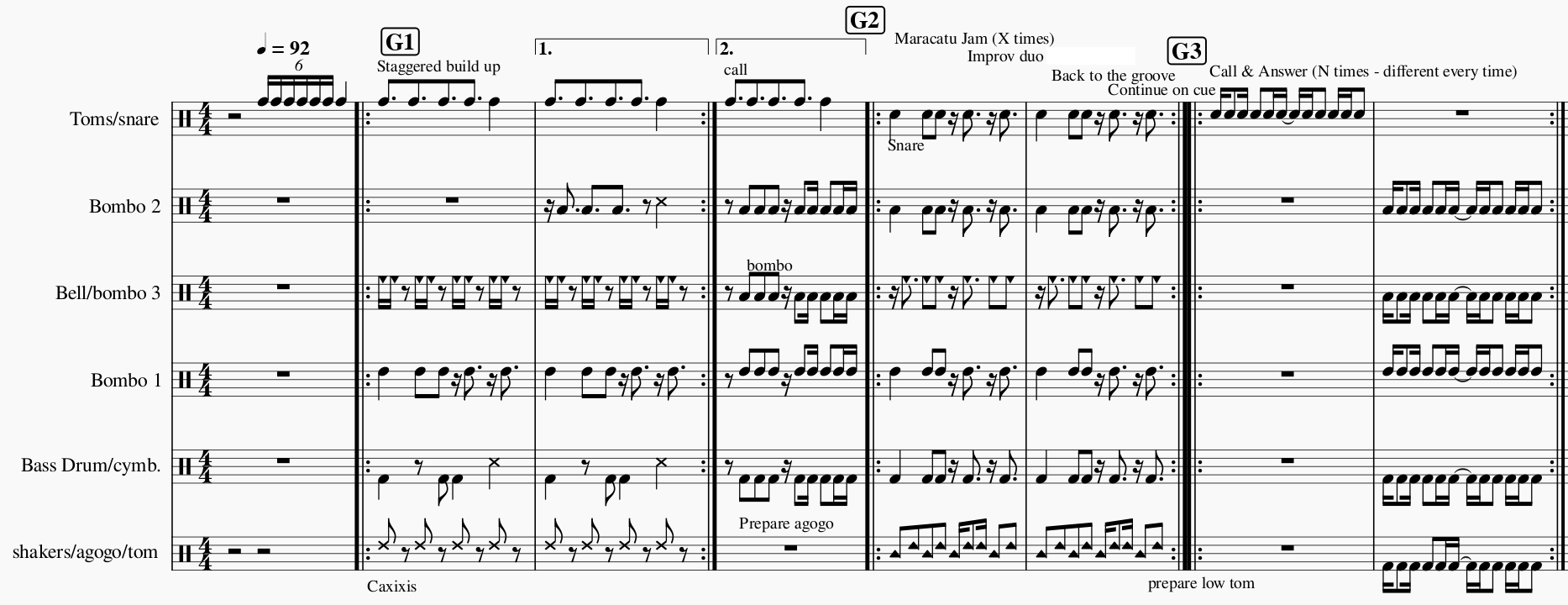

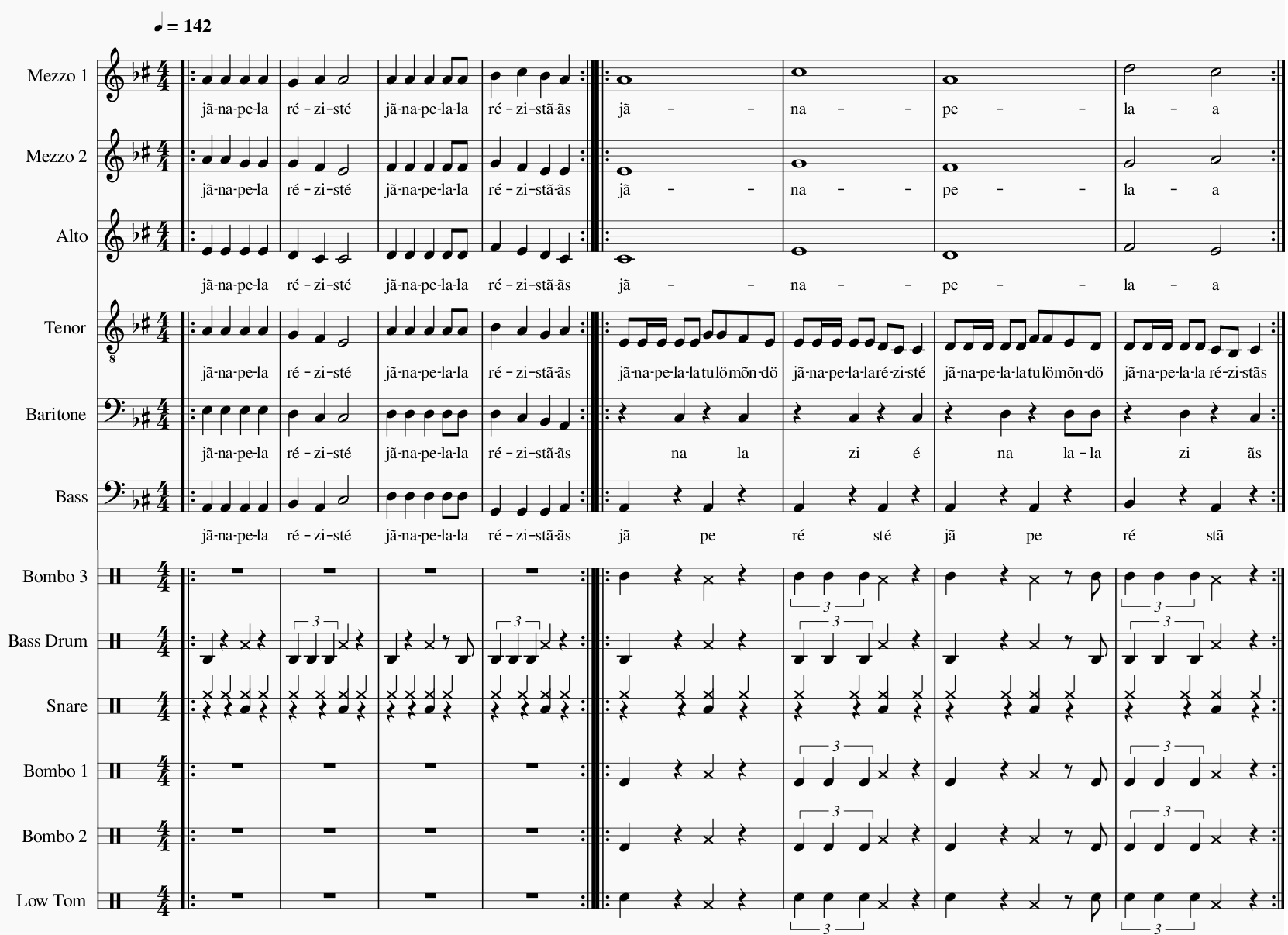

Figure 9 - Score extract of the sixth part - voices on the first half

It is sung in heterophony with two main rhythmic movements calling and answering each other (higher voices and Baritone on one side, Tenor and Bass on the other), while playing different patterns on the percussion that interlock into a complex tapestry of binary and ternary rhythms, resulting in multiple 2:3 and 3:4 polyrhythms. Built up piece by piece, this first half culminates with a percussion buildup ending with a magistral drop that leads straight into the second half.

Figure 10 - Score extract of the sixth part - percussions

The Mezzo-Soprano 1 starts the second half alone on this one-note ostinato, marking every beat. After one cycle (the lyrics later bring a cycle of 16 beats) the Mezzo-Soprano 2 joins in and answers on every off-beat with its own one-note ostinato. Hence, the new groove is composed of interlocked quarter-notes on- and off-beat between the two highest voice.

This duo sounds like an alarm beeping, an idea that came admittedly from La Grande Folie. However, the interplay between the two voices has an additional dimension here, as it is also within the text: the first voice, alone at the beginning, seems to sing “Je vais laisser ma terre, c’est gai. Je veux partir, tu sais c’est gai” (“I will leave my land, it’s jolly. I want to leave, you know, it’s jolly”), but when the second voice adds syllables in between, the meaning turns out totally different “Je ne vais pas les laisser, c’est ma terre (terre), mais c’est la gue-guerre. Je ne veux pas partir, tirer, tuer, c’est comme c’est, la gue-guerre” (“I will not let them, it’s my land (land), but there is a wa-war. I do not want to leave, shoot, kill, but it is what it is, wa-war”)

Then the Alto comes in, harmonizing the first voice and uncovering a harmonic movement although the first two voices never change pitch. The two lower voices accompany with the same ostinato they had in the first half, bringing a more elaborate harmony, while the tenor brings in a new, fast, syncopated pattern (at the 16th-note level), adding to the general agitation of all the rhythmic ostinatos.

7. La fuite (The escape)

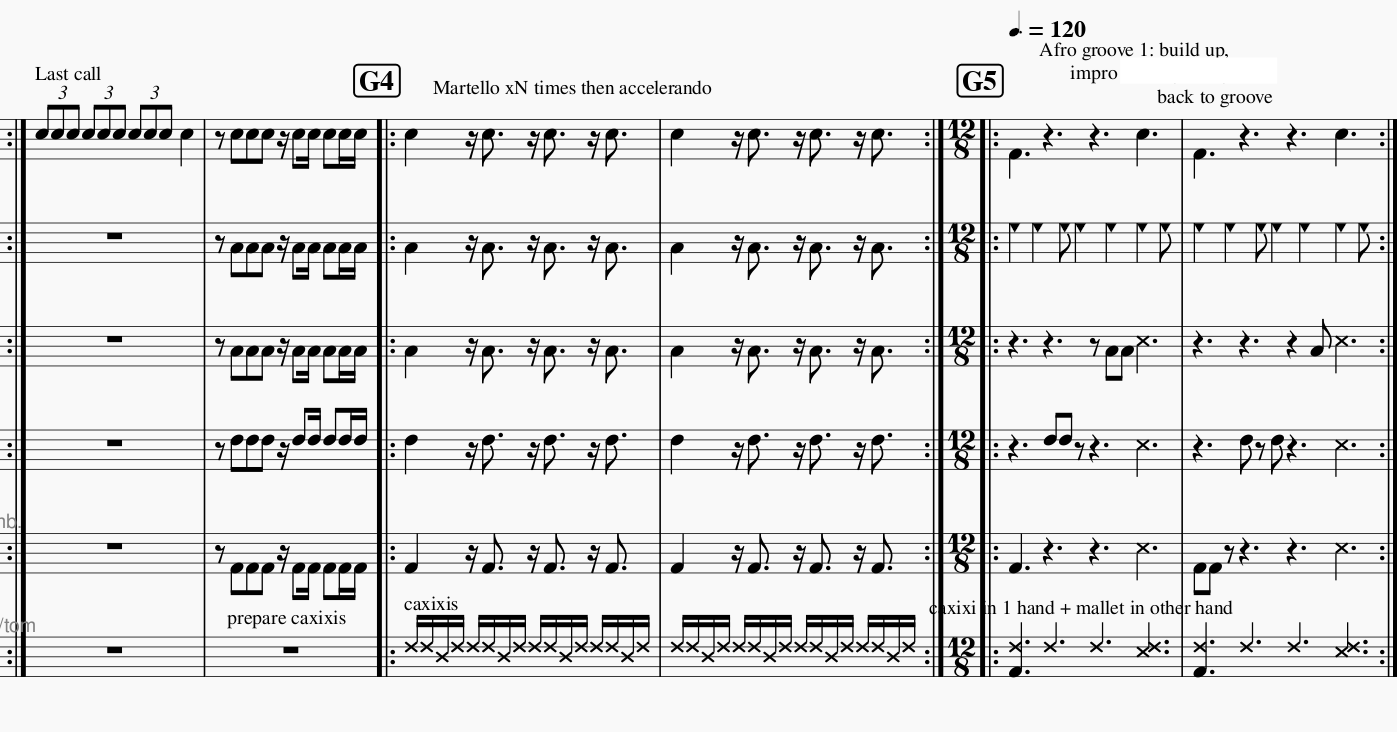

The next section figures this run-away and Pierrot being chased by the army. It is an instrumental part, featuring percussion instruments only. I wanted to put forward the percussionist side of the band at some point in the suite, and it made sense for the story: this escape, running and chasing is adequate to a percussion moment.

For that section, far from any Occitan tradition, I took influence from other parts of the world and borrowed a few foreign elements: a bell pattern from the Afrobeat style (modern East-African genre), the Maracatu rhythm (from the North-East Afro-Brazilian eponym tradition), and the afro-clave in 12/8 that is present in or has influenced many African and Afro-Latin traditions.

The section starts with a slow, binary bass drum beat call to which an off-beat syncopated tom answers, both accompanied by a regular afrobeat bell. Then the groove slowly turns in to the Maracatu rhythm.

Maracatu is a rhythm that I find powerful, both for the ones who play it and the ones who listen to it. I wanted this power to be felt by the musicians, and by the audience. It is also a way to quote this rhythm that I particularly like.

Here, the intention is not to evoke the imagery from the Maracatu culture, the orixas (deities, religious figures) and spirituality associated with it, nor the carnivalesque idea commonly associated with this rhythm that is similar to samba. There is a risk, however, that the audience get the wrong picture and associate it with carnival and party. But I counted on the story to keep the audience focused and let them interpret the rhythm accordingly.

The pounding of the low drums is here to reflect the fast and strong heartbeat of Pierrot who is running and escaping from the army, while it also figures a battalion marching in a military style, stomping on the floor in time, getting closer and closer. At the same time, the snare drum gives a hint of military drum that fits the scene perfectly.

The Maracatu moment features a duo improvisation between a bombo and the snare drum, figuring the chasing between Pierrot and the army. The snare drum can then sometime sound like gunshots, as if Pierrot was being shot at during his escape. Eventually, the Martello variation of this rhythm is played, and the pace is accelerating, going back to the image of Pierrot’s heart beating faster and faster.

Then comes a sudden change of time-feel into a ternary 12/8-time part starting with the afroclave alone on the bell, in stark contrast to the previous rhythms (Maracatu and Martello) which are clearly binary, and which suggests a change of scenery, a new landscape.

I particularly like this bell pattern that is found in many places. I tend to use it very often, intuitively, as soon as the rhythm is ternary and seems compatible: it is deeply ingrained in my musicianship. Because it is in 12/8, it also naturally opens the door to various polyrhythms, such as 3:2 and 4:3. In fact, one can count it in 3 groups of 4 subdivisions (binary) or in 4 groups of 3 subdivisions (ternary), giving two versions with a very different feel. Here I used it in its ternary feel.

The groove I composed on top of the afroclave is, as far as I know, original. It would be hard to map out the influences that might be at play here, it is part of the dense mix that is contained in my musicianship, and that is constantly evolving, including new rhythms as I learn and practice them. This 12/8-time part also features an improvisation moment between two bombos, which again reflects the interplay between Pierrot and his pursuers.

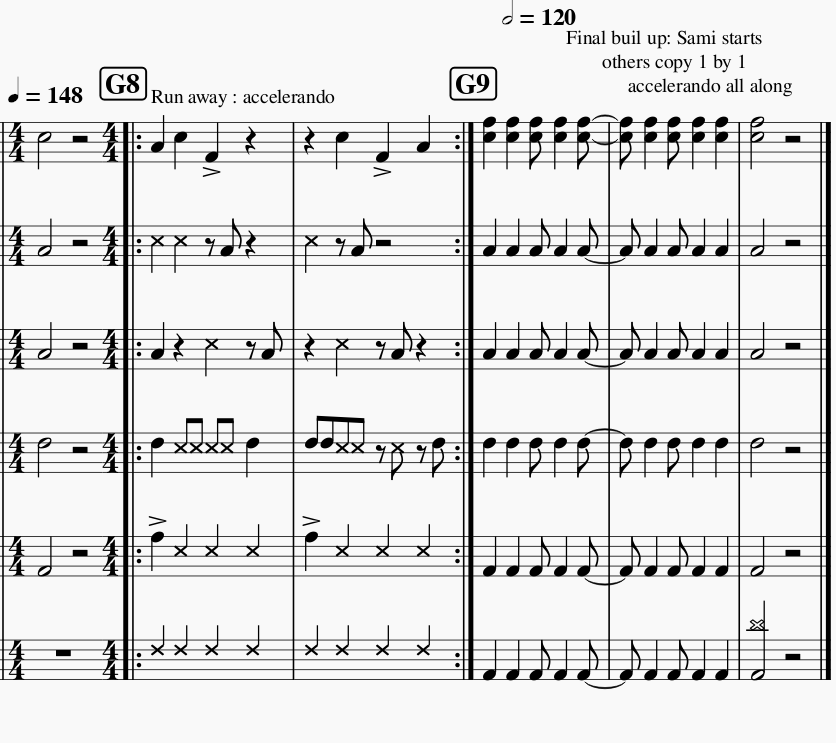

Last, the third part of this instrumental section figures the running away. It’s the final accelerando, the final sprint, after which Pierrot will end up free from his pursuers. The time-feel again changed back to binary, but this time much faster. And the pulse keeps accelerating, until the ultimate buildup: Pierrot finally manages to escape, and ends up in a safe place where the police or the army cannot get to him, in the mountains.

8. Le retour (The return)

This section comes after a longer storytelling part. Time has passed, the frontline is not anymore at Pierrot’s doorstep, but his land is now occupied. He decides to go back home to his family, and discover both how the war has destroyed his hometown, and how his people are mistreated by the occupying power.

In this section, the music is a cry of despair. It thus felt natural to call back the opening theme, which already contains the seeds of this feeling. I slightly rearranged it by exchanging parts between the lower voices with the higher voices, transposing one octave down or up as needed. In this case, the range is even more compact and the Tenor and Alto voices even cross towards the end.

It is like an “inverted” version of the opening, which echoes its feelings. With more intensity, louder dynamics, as well as with the main center of harmony and dissonance in the Tenor range, it brings even more tension to show the shock and the despair of Pierrot discovering his devastated land and the condition in which his people are kept under occupation.

The last two sections of the suite are the most recent additions to this work. In terms of the time of composing, they are quite distant from the other parts, which could explain, partly, why they are different. Although they follow a similar type of structure as most of the previous sections, the groove is totally different, and the singing style also is. I wanted a more resolute and decisive approach in this last part because in the story, that’s when Pierrot turns his despair and indignation into a resolute energy, a search for a solution, he protests against the injustice of the occupation, and eventually starts a resistance movement with his community.

9. Il faut faire quelque-chose (Someone has to do something)

In this penultimate section, the meter goes back to a ternary 4 beats, but I used a heavy drumbeat, that could be heard in some hard-rock, metal, or even hip-hop context, although it is maybe less common in ternary. The basis of the rhythm is held here by the bass drum, snare drum and hi-hat. Other percussion elements are here to reinforce the ternary feeling, adding some layers of interlocking patterns to bring more intensity as the section progresses.

In this part of the story, Pierrot turns his sadness and desperation into anger, and into a search for a solution. Things cannot continue as they are. He is resolute. The marcato-tenuto way of singing, as well as the heavy rhythmic basis echo this resolution and decisiveness. The texture of the voices is homophonic, with a lot of parallel movement, giving this feeling of block chords, much like a brass section.

The lyrics are “Je ne vais pas rester les bras croisés. Je ne vais pas rester sans rien faire” (“I am not going to stand by and do nothing.”)

The section also features one improvised vocal solo part for the Alto, and another improvised duo part, in the form of a challenge between two of the percussionists. It ends with a sort of choral, with a rubato solo on the Tenor: “Il faut bien que quelqu’un fasse quelque-chose” (“Someone has to do something”).

10. Resistance !

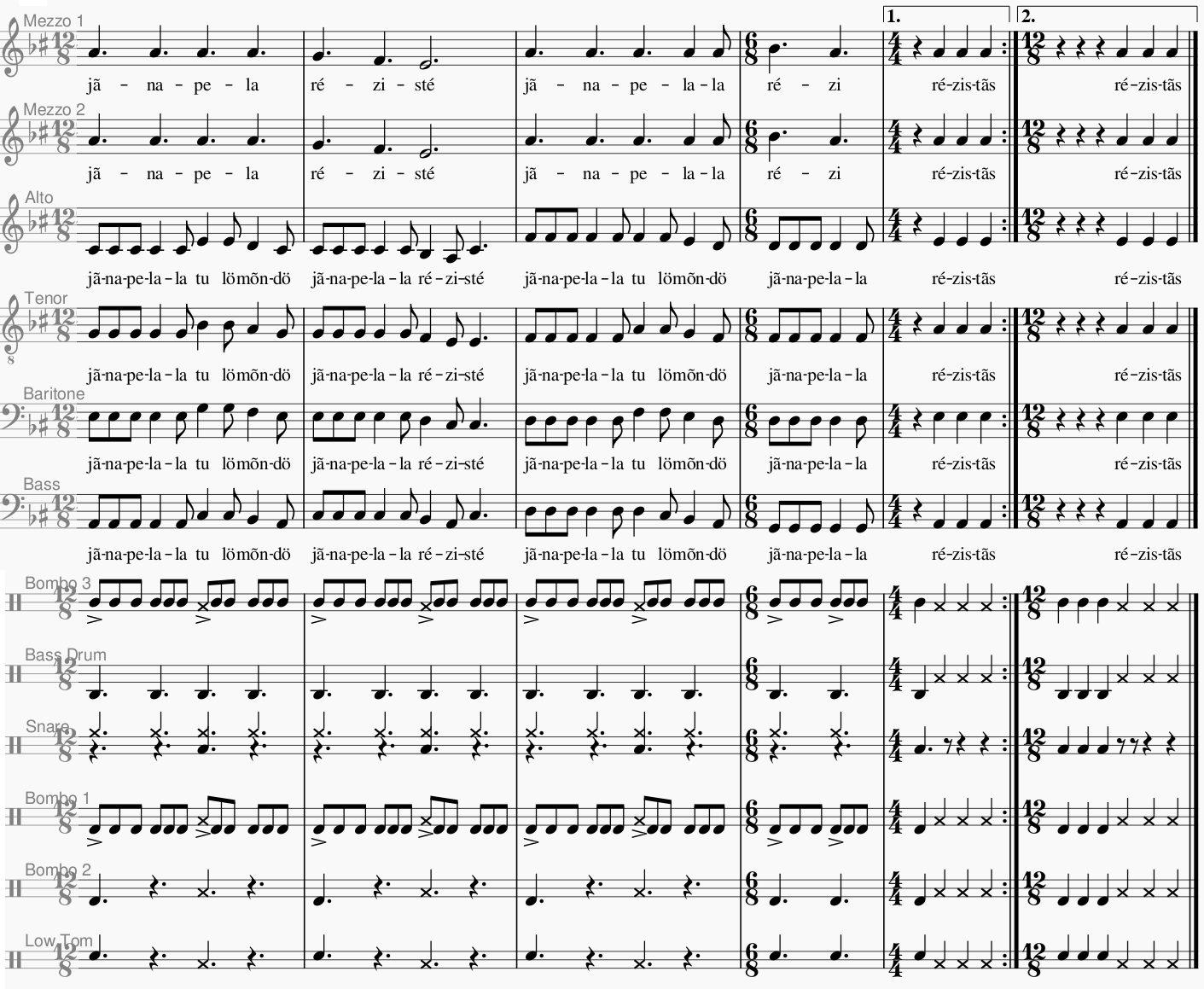

The final movement starts with a similar construction as the previous section, but the rhythm starts with a mixed binary/ternary heavy groove, leaning more on the side of hip-hop style. This last section is however more complex than the previous one as it features several variations on the main voice groove, some metric modulations, and lots of breaks.

In the first variation, after a sudden break, the Tenor takes a solo voice on a fast binary rhythm (in 1/16th notes) while the Bass and Baritone sing a call and answer in duo, reminiscent of what the higher voices sung in the second half of the sixth part (Le refus). The higher voices lay down long notes like a choir background. Half of the percussion accompany this part, in unison with the drumbeat from the beginning.

Then the two Mezzo-Sopranos take over and sing in unison the main melody (which was on the Tenor part at the very beginning). The percussion gradually fades out.

Another hit breaks the flow again and a sudden speed up comes in when the Tenor takes the lead again with a new solo, accompanied with unison hits from the whole percussion section. Here starts a series of breaks that will punctuate the end of each cycle until the end.

After a second round, the percussions come in with a fast ternary rhythm and the Tenor voice adapts its line to this new time-feel. The two lower voices come in to harmonize the lead voice, as well as the Alto voice, while the two Mezzo-Soprano eventually add the main theme on top: “J’en appelle à résister. J’en appelle à la résistance” (“I call to resist. I call for resistance.”)

The pulse of this last part is faster, and the groove slowly turns into a rhythm close to ragga or reggae-dancehall. The rhythm of the singing is also flowing like ragamuffin, which fits with the call for action and social justice.

Eventually, the whole band performs a series of breaks in unison, built on a metric modulation between 6/8 and 3/4 times, featuring calls and answers between percussion and voices shouting “Resistance!”. The breaks also contain added beats, first breaking the flow, eventually coming together as a 6/4 reading of the 12/8 metric.

The ending is shouted while the percussions give a unisono final build up and ending break.