In this reflection, I examine the entire process, drawing comparisons between my own work and that of other artists, while also considering the role that choreomania played in the process of shaping performance try-outs.

Choreomania and the Residency Programme

The central question driving this research was: how does choreomania influence my creative process and shape my performance practice as a classically trained pianist? Answering this first required an exploration of a key sub-question: how can unveiling the genealogy of choreomania provide new insights into contemporary performance-making? Investigating choreomania as a shifting set of concepts intertwined with power and control deepened my understanding of its historical roots while opening new perspectives in my artistic process. In the second chapter, I examined choreomania’s genealogy and its connections to today’s social, political, and artistic spheres.

As identified in the third try-out (5.3.4), the redefinition of “disorderly” movement - those socially unaccepted forms of bodily expression - not as a symptom of disease but as a natural occurrence, played a crucial role in shaping both the conceptual framework and the narrative of the experimental playground. From the outset, the first and second try-outs explored movement as a necessary tool for political action and personal resilience in times of crisis. This inquiry was heavily influenced by Kélina Gotman’s identification of choreomania as a mechanism of control over mass movements in public spaces and Bogomir Doringer’s study of body politics in dance floors, raving culture, and protests, emphasising the inherent political nature of movement.

The third try-out further reinforced these ideas through my own physical experience - liberating myself through movement and exhaustion, a practice previously absent from my artistic vocabulary. How does seeing a classically trained pianist jump to the point of exhaustion while the audience enters the performance space shift our perception of what it means to be a pianist? My practice continues to challenge rigid artistic roles, embracing a non-hierarchical, fluid conception of the performer’s place. This urgency to reframe the performer’s role has never been more visible in my work.

Process and Methodology

A pivotal question also emerged: How does analysing other artists' processes influence how I shape my own work? Initially, I saw the residency at DOOR Foundation as an opportunity to observe the creative process of five movement and performance artists, anticipating that their approaches would serve as a foundation for my shaping of performances. However, my time there challenged this notion - it did not simply inform my process but reshaped my conceptual framework around choreomania. Instead of treating theory and practice as separate research phases, I began to see them as deeply intertwined. ELLE’s approach of embracing choreomania as a methodology, rather than using her practice to depict it, prompted me to adopt a more rhizomatic process. I stopped viewing my research as a linear progression and instead embraced its unpredictability - like watering seeds at different times and in varying amounts, allowing spontaneous ideas about future try-outs to develop alongside in-depth historical and medical inquiries, each growing in its own way. This meandering became a choreography in itself, reflected in the journals, which I deliberately left in their original format - a spontaneous interplay of fragmented notes, reflective passages, and non-linearthoughts.

This integration of theory and practice also expanded my understanding of movement. As someone outside the dance world, I initially saw movement practices as rigid and restricted to certain disciplines. Through the insights of Kélina Gotman and the movement artists I engaged with, I realised its potential as a fundamental tool in performance art. This shift in perspective allowed me to challenge my own assumptions and push my artistic boundaries, incorporating disorderly motility, erratic gestures, anger, vulnerability, exhaustion, pain, and the limits of the body - not just as expressive elements, but as political acts within the performance space.

Beyond movement, the residency illuminated a broader truth: there is no single creative process. Each artist had a distinct approach, yet all navigated a constant negotiation between comfort and discomfort, safety and risk. The three artists I focused on - ELLE FIERCE, Alexandra Cassirer, and Aun Helden - did not treat choreomania as an external reference but as something that fundamentally altered their processes. This deeply influenced my own approach. Rather than mimicking choreomania or using it as a thematic layer, I integrated it as a lens through which to filter performance ideas, shifting my theoretical framework away from historical and medical archives and toward contemporary artistic practice.

Negotiation and Audience Engagement

Even though I had begun experimenting with long-durational practices in my 8-Day Performance, I would have never approached exhaustion in the way I did without my explorations into choreomania, my discussions with Alexandra Cassirer on performance art, Bogomir Doringer’s insights on the political body and raving culture, and the exercises suggested by Ekin Bernay in her collective workshop.

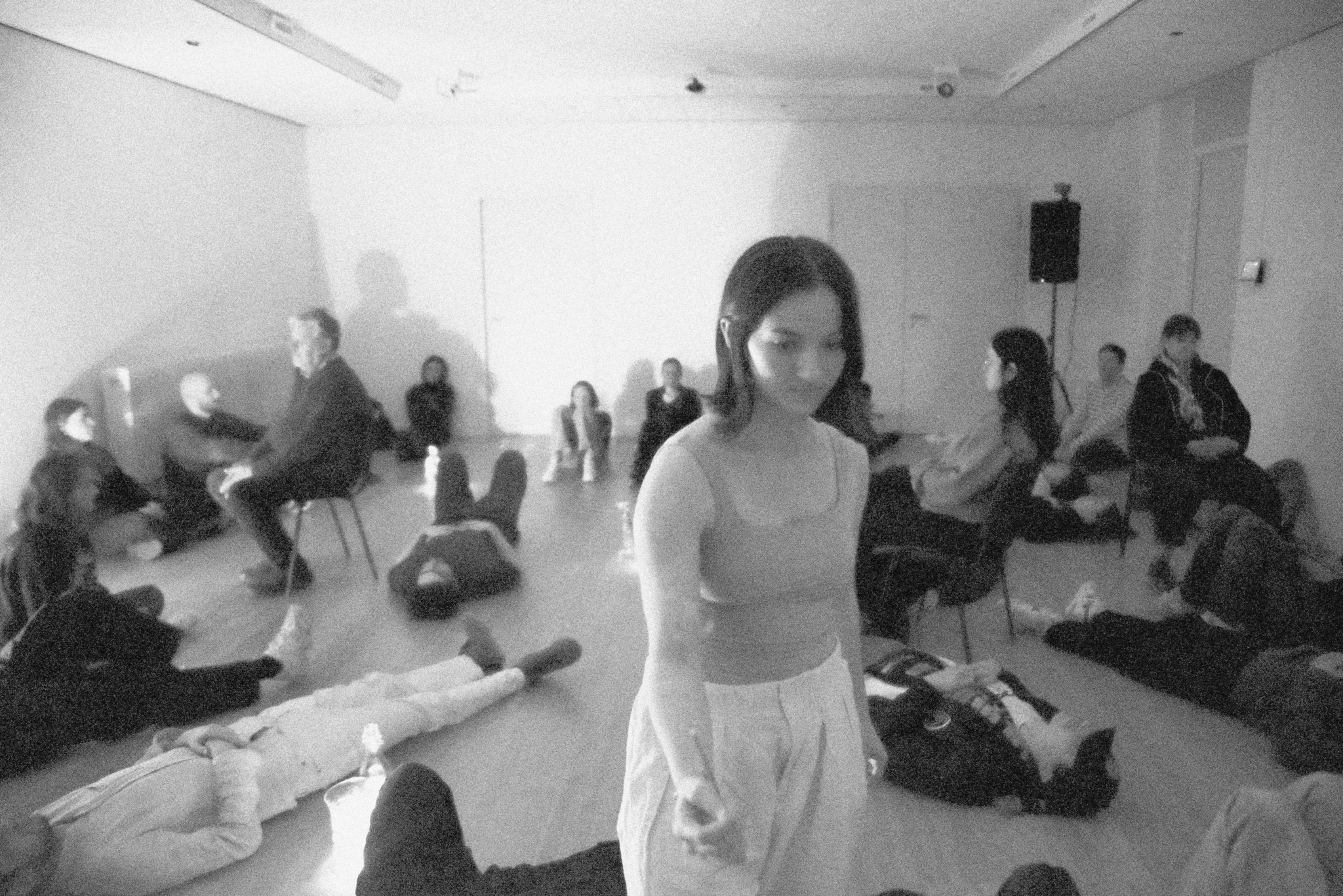

The negotiation between comfort and discomfort, safety and risk, branched out in another direction in the experimental playground, particularly in try-out 2 with the audience conversation. From the moment participants were encouraged to introduce themselves to those nearby, a negotiation unfolded - between individuals and the space, between participants and performers, among the collective, and within themselves. This was most evident when I handed over the floor entirely to the audience, allowing them to decide whether to share their thoughts or embrace silence.

On Collaboration

Collaboration has been central to the development of this research - first through observing the five artists-in-residence and later within my own experimental playground. Within the practical phase, we navigated a spectrum of working relationships, drawing from Hellqvist’s experience with Taylor’s topology of hierarchical, cooperative, and collaborative dynamics (Hellqvist 2025). Initially, interactions leaned toward a hybrid of hierarchical and cooperative structures, particularly in try-out 1, where dramaturgical elements such as movement improvisations, text, and audience feedback reflected this blend. By try-out 2, however, these same elements had evolved into a fully collaborative process, as evaluation of the previous performance and development of new ideas became a collective, cyclical effort.

This awareness of hierarchy within collaborations also shaped my understanding of audience participation. The audience conversation emerging in try-out 2 began as a cooperative process. However, as their exchanges actively shaped the piece in real-time, this interaction transitioned into a collaborative one, where their role extended beyond mere evaluation to co-creation.

Expanding Interdisciplinary Performance Frameworks

This research builds on Joel Gester’s (2021) framework for interdisciplinary performance by identifying a fifth form of interaction, adding two new components, and proposing a fourth role of actions.

- Fifth form of interaction:The exchange between audience members themselves, which is particularly evident in the audience conversation.

- Two additional components:

o Atmosphere - a crucial yet fluid aspect that aids in shaping the concept, narrative, and rhythm of a performance. It is a variable, expressive component. It evolves throughout the piece and plays a key role in audience-performer and performer-performer connection.

o Timeframe - an often-overlooked factor that fundamentally influences artistic decisions. It can be set or variable. A fixed deadline imposes structural constraints, while a flexible one allows for a more organic evolution of ideas.

- Fourth role of actions: During the dramaturgical unit of exhaustion in try-out 3, Giuliana and I identified a role beyond Gester’s existing categories of leading, accompanying, and contrasting actions. We termed this the simultaneous or parallel role - neither fully leading nor merely accompanying. As we pursued a shared goal (liberation through exhaustion and pain), our focus remained intensely individual, inducing a quasi-meditative state. This hybrid role blurred hierarchy, embodying a form of co-leadership that embraced both collective and individual experiences.

Navigating Hybridity in Artistic Processes

The tension between individual and collective processes has been a recurring theme. During the residency, this became apparent in Aun Helden’s work - while her performance was ostensibly individual, the creative process had so fully absorbed its environment that the outcome was inseparable from the collective experience. Similarly, my own try-outs frequently defied disciplinary boundaries, revealing how rigid categorisation limits our understanding of both performance and choreomania. Viewing choreomania as a fixed historical phenomenon ignores its genealogy (the discourses and side-stories of control formed around it); similarly, viewing artistic disciplines as discrete containers ignores their fluid intersections. Through this research, choreomania has become more than a subject of study - it became a lens through which I examine the shifting, hybrid roles within performance.

This shift is exemplified in the evolving role of the piano within my practice. Once the dominant force in shaping my performances, it has now become one element among many. No longer the primary protagonist, it coexists within a broader, non-hierarchical interplay of disciplines. I no longer begin with music when crafting a performance; instead, I first sculpt the concept, allowing the music to emerge as a supporting element that serves the performance’s intention.

Audience interaction and Participants’ Performance

The audience conversation transformed participants into active performers, making their input essential to the piece. Far from a structured feedback session, their spontaneous exchanges shaped the rhythm of the performance, with their choice of words, timings, and even laughter becoming part of its organic flow. This collective act not only blurred the boundaries between performer and spectator but also revealed underlying hierarchies. During the initial instruction, participants were encouraged to speak with those nearby, yet despite standing among them, Giuliana remained unapproached. She observed as conversations unfolded around her, yet no one included her, as if her role as a performer unintentionally set her apart. This moment highlighted how ingrained power dynamics persist even in spaces designed to dissolve them.

Additionally, the decentralised nature of these exchanges expanded the performance’s scope - no participant could grasp the full scope of what was said, as each individual experienced only a fraction of the whole. This diffusion of authorship may explain why the traditional ritual of post-performance congratulations disappeared. Rather than fulfilling a social obligation after the piece ended, participants had already shared their thoughts in real time, in a space where their voices carried weight. The performance had absorbed their responses, making them feel more immediate and authentic. In this way, the conversation challenged the formality of post-performance praise, dissolving it into the work itself in a way that felt far more honest and real. After all, who congratulated them?

Re-examining Interaction and Connection

Building on my experience of non-interaction during the 8-Day Performance, the experimental playground in this research has pushed participant engagement to the opposite extreme - introducing direct physical contact with the audience. While the 8-Day Performance might have appeared to stem from a need for isolation, at its core, it was driven by a deeply social nature and a constant eagerness to connect from a more genuine and non-hierarchical position. I felt I had to always be present, meeting others’ expectations, so I chose instead to always be present while never fulfilling them. This process became an opportunity to re-examine relationships - both between people and myself - questioning how interactions are personally navigated and how this exploration reverberated with others.

Later, while improvising movement during the second try-out, I broke the fourth wall, meeting the audience’s gaze in a moment that felt familiar. I was fully present, yet silent. My instinctive response was to approach individuals and make gentle physical contact—a way of negotiating the tension between my presence and the absence of verbal engagement. This action was unplanned, emerging spontaneously within the improvisation, yet it became a pivotal moment in reconsidering the dynamics of audience-performer interaction.

Moreover, linking this to my initial reflections on integrating audience feedback within the performance itself, a strong desire emerged to actively acknowledge participants’ roles. It was no longer enough to reflect on their contribution; there was a need to make them realise that they are not mere observers but active co-creators of the performance. The space we occupy is shared, the hierarchical roles shift from performers to participants, and their reflections are not just an outcome of the performance but a fundamental part of its construction. Their choices, reactions, and presence do not shape something pre-existing - they generate the performance itself. The performance does not exist independently of them - it unfolds through them.

Next Steps and Future Plans

Since the last performance, work has already begun on Choreomaniac Seeds Vol. III, which will be presented on March 26, 2025, as the final session of CAN YOU HEAR THAT?! at HaagsPianoHuis. This marks the fourth try-out of this ongoing research project, which I hope will continue expanding in multiple directions, evolving through each volume.

The concept of this next performance originates from the idea of life beyond life - an imagined suspended space beyond time, matter, or language, yet charged with an undeniable presence of energy. The early stages of this piece have been profoundly shaped by personal loss - just days after the third try-out, I lost my best friend. This rupture is now embedded in the thematic evolution of Choreomaniac Seeds: the first volume embodied anger, vulnerability, and fear; the second sought liberation through pain and exhaustion. In this trajectory, the fourth try-out naturally evokes Paradiso, the final volume of Dante’s Divine Comedy, symbolising transition and transformation. This time, we intend to engage the audience in a more direct way from the beginning. Giuliana and I have also considered the possibility of a silent or still performance - an idea that surfaced during try-out 2 after reading philosophical essays on permanent productivity (Annex F, entry November 26). A selection of the journal for this try-out process can be found in Annex J.

[The following photographs were added after completion of the fourth try-out, after submission and evaluation of this research.]

Beyond this next iteration, I aim to continue exploring new directions for the research. Future areas of inquiry include:

- Long-durational performance

- Performing in public spaces

- Further investigating the concept of otherness

Each new phase of this research reaffirms the importance of hybridity, fluidity, and the breaking of traditional hierarchies within performance. As Choreomaniac Seeds evolves, it continues to challenge not only how performances are structured, but how we understand presence, authorship, and the very act of performance itself.

This one-minute video teaser from Choreomaniac Seeds Vol. I is another outcome of this research, intended to promote and support the project's future plans: