Throughout the experimental playground in the next chapter, I explore the process of shaping my performances in collaboration with other artists. These try-outs mark the first time I incorporate movement into my artistic practice and approach piano and voice through a distinct lens. This chapter introduces key ideas on collaboration, movement, the use of voice and piano in my performances, while also outlining the perspective through which I examine the development of these performances in the following chapter.

4.1 Collaborative practices

My approach on collaboration in the practical phase of this research has been informed primarily by Sanne Bakker’s Master’s research Creating an Audiovisual Performance Through Interdisciplinary Collaboration (2024) and by Karin Emilia Hellqvist’s PhD thesis Solastalgia - Toward New Collaborative Models in an Interdisciplinary Context (2025).

Bakker presents a table that visually highlights the four key qualities of successful interdisciplinary collaboration, as identified by Karen Scopa:

This table concisely outlines key aspects of collaboration that provide a good foundation for approaching interdisciplinary creative processes. Applying these principles was essential in developing the performance try-outs, with a strong emphasis on strengthening shared ownership - not only among performers but also with the audience. By making the audience a part of the performances, as you will see in Chapter 5, I sought to apply these concepts to the often-overlooked collaboration between performers and audience members (or participants).

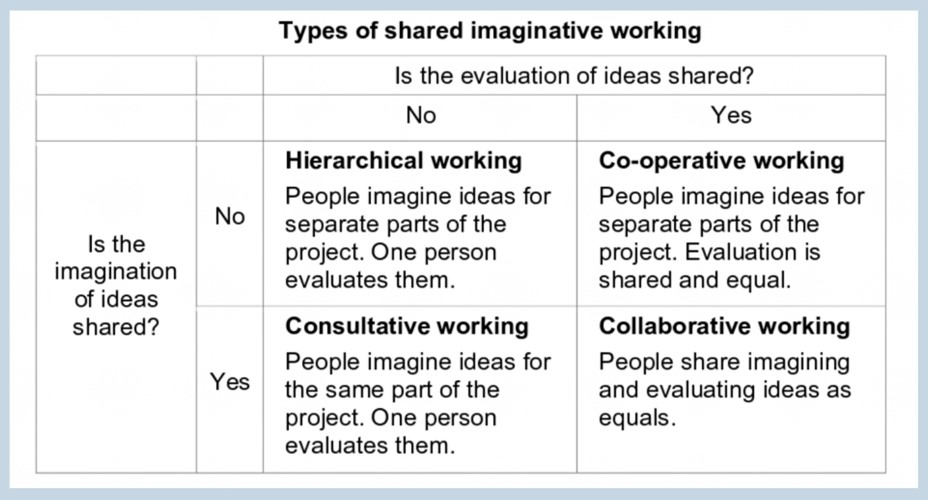

A broader perspective on the collaborative dynamics is discussed by Hellqvist, drawing from Alan Taylor’s topology of working relationships:

This table (figure 3) is highly insightful, as it not only clarifies the key characteristics of successful collaboration but also identifies specific actions that shape different types of interactions. The four possibilities Taylor identifies are hierarchical, co-operative, consultative, and collaborative working. If the imagination of ideas is not shared, the resulting working environment can only be either hierarchical (if the evaluation of ideas is also not shared), or co-operative (if the evaluation of ideas is shared). Similarly, if the evaluation of ideas is not shared, the resulting working environment can only be either hierarchical (if the imagination of ideas is also not shared), or consultative (if the imagination of ideas is shared). Collaborative working can only emerge when both imagination and evaluation of ideas are shared. Notably, it adopts a less judgmental tone by avoiding a binary evaluation of success or failure, instead focusing on how certain actions (imagination and evaluation of ideas) influence the collaborative process. Moreover, drawing from her own artistic practice, Hellqvist highlights the fluctuating levels of interaction throughout the creative process. Citing John-Steiner, she reinforces the importance of a “shifting rhythm of interaction” (Hellqvist 2025), which she experienced during her process with another artist, identifying herself fluctuating within co-operative and collaborative working.

4.2 Movement

The most significant and visible influence of the previously outlined research framework on my creative process was my first deliberate exploration of movement in performance. My interest in movement began when I started reading Gotman’s book and encountered her formulation of choreography as “a manner of articulating a concept and practice of -and in- motion; of irritating the border between these; irritating the very notion of border” (Gotman 2018, 2). This perspective intrigued me, as it expands choreography beyond structured movement, framing it as a broader reality that engages with the disruption and redefinition of boundaries - both conceptual and physical. Gotman further expands on this idea, arguing that choreography is “the very motion of bodies - books, pens, people - carrying this form, translating and further transforming it” (idem, 3). This broader, more fluid definition of choreography encouraged me to reconsider movement beyond dance, allowing me to experiment with how physicality, objects, and even spatial relationships contribute to performance.

Furthermore, observing how some artists at the residency engaged with movement beyond dance was deeply inspiring. I vividly recall conversations with Alexandra Cassirer about her practice and performance art; these and other moments reshaped my own perceptions - or even prejudices - about dance, leading me toward a more expansive and open understanding of it.

Throughout the experimental playground, my exploration of movement was not driven by the intention to dance, but rather by a focus on the instinctive, everyday actions that define human behaviour. How does my body move when I fully express anger instead of suppressing it? How does my walk change when I am in a hurry? What trajectory - or choreography - does my gaze follow when I push my limits? These are some of the questions that emerge throughout the creative process, guiding my investigation into the body's natural, unfiltered movement.

4.3 Voice and piano in my performances

Throughout the try-outs, the voice is not approached as a trained instrument but rather explored in its natural, everyday functions. The focus shifts to how the voice emerges in daily life - through speech, breath, exclamations, murmurs, lullabies, or moments of silence. This approach seeks to uncover the raw, instinctive ways in which the voice expresses emotion, urgency, and human presence beyond conventional musical parameters.

However, as a classically trained pianist, the relationship with the piano takes on a hybrid functionality. Depending on the performance's concept or the specific idea being explored, the piano's role shifts between a refined, technical approach and a more instinctive, human interaction. Above all, the most significant shift in my use of the piano in these performances is its subordinate role: the choice of music is determined by the performance’s concept, rather than the other way around.

4.4 The process of shaping interdisciplinary performances

In his research, Joel Gester (2021) develops the Map of Components, a framework for interdisciplinary performances with classically trained musicians, dancers, and actors. This tool forms a key foundation for my work, which I will expand on in Chapter 5 to analyse both the creative process and performances. Here, I will outline its key principles.

For Gester, components are what constitutes the common ground between disciplines. He sorts components into three main blocks: physical or dynamic, expressive, and abstract. Physical components are made up of the venue, with its stage/space, performers and public. They interrelate with two other components: disposition and interaction. Interactions can take four different forms: interaction within a discipline, interactions between disciplines, interactions between performers and the public, and interactions with the venue.

Expressive components - intention, action, and expression - are fundamental to interdisciplinary performance. Intention gives purpose to action, which can take a leading, accompanying, or contrasting role. Expression happens simultaneously with intention and action, conveying emotions or images in concrete and abstract forms. Expression generates impressions on performers and the audience, shaping how the performance is perceived and experienced.

Abstract components - concept, narrative, dramaturgical units, and structuring elements - form a stable yet flexible framework for interdisciplinary processes. Concept guides artistic choices and evolves throughout the process, while the narrative shapes progression and coherence without needing a linear storyline. Dramaturgical units function as structural building blocks, grouping actions, intentions, and conflicts into meaningful sections. Structuring elements act as specific sub-concepts that refine the overall vision.