The histories, stories, and names of Chinese migrant workers on the U.S. Transcontinental Railroad have remained in the shadows for over a century. In 2014, the Chinese railroad workers were inducted into the U.S. Department of Labor's Hall of Honor. But this alone does not heal the historical trauma nor does address the deep-rooted racial issues. By digging into online archives, this research aims to initiate a dialogue, acknowledge the absence, and make the invisible Chinese immigrant workers visible via artistic interventions. The study seeks to give form to and inspire dialogues about these invisible workers by employing arts-based research methods to produce works that honor their histories and sacrifices.

The Transcontinental Railroad, completed in 1869, was a monumental achievement of America’s Manifest Destiny and the 19th-century westward expansion. The railroad successfully linked the eastern rail lines of the United States to the West Coast, enabling travel across the continent at unprecedented speeds. A total of 20,000 Chinese workers were involved in the construction of the railroad, and over 1200 Chinese workers died of avalanches, explosions, and accidents in the region of Sierra terrain near Donner Summit (Lin 2019).

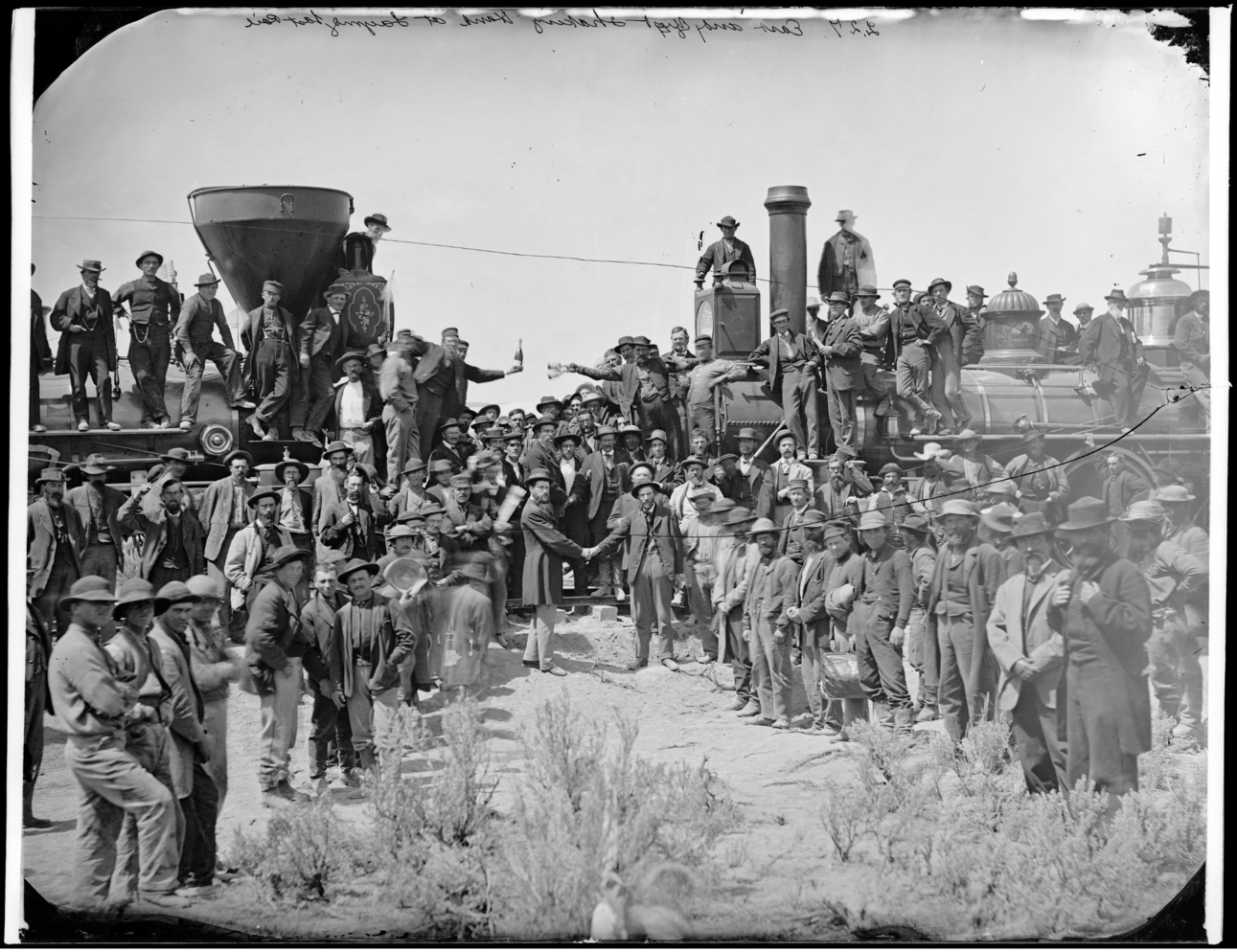

The stories, contributions, and names of these Chinese immigrant workers have been omitted from the mainstream American historical narrative. In 1969, During the centennial commemoration at the Promontory Summit, Secretary of the Interior John Volpe proudly asserted that only Americans made the achievement possible (Chang 2019). The San Francisco Chronicle echoed this sentiment in response to Volpe’s speech: ‘Who else but Americans could drill tunnels in the mountains 30 feet deep in snow? Who else but Americans could chisel through miles of solid granite? Who else but Americans could have laid ten miles of track in 12 hours?’ (Hushka, R., et al. 2017). The iconic photograph that commemorates the completion of the transcontinental railroad, Andrew J. Russell’s ‘East and West Shaking Hands‘ displays two large steam engines, representing the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) and the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) head-to-head (Figure 1). The train engines are surrounded by a crowd of workers, businessmen, and officials who gathered to witness one of the nation’s first ‘great media events’ (Khor 2016: 433). Not a single Chinese worker appears in the crowd.

The Historical Background section of this paper explains the historical context and factors that drove Chinese immigration to America in the middle of the nineteenth century, and how those workers came to fill the labor need of the CPRR. The next section examines Questions of Representation in relation to Chinese migrant workers. And the Making the Invisible Visible section presents the arts-based research utilized to explore these workers’ legacy in the hope of generating new recognitions and dialogues. The described artworks include the signature piece The East and the West, which was physically installed as a wall-length mural (2 meters x 5 meters) in the Georgetown University Car Barn, as well as a series of works that respond to archival pieces and stories. The final work, Collapse (崩), utilizes the method of Blackout poetry to discover hidden meanings and reframe the contents of the United States’ Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

These works transform quotes, expressions, texts, and the hardships of the Chinese railroad workers into points of dialogue and reflection. The project cannot provide, nor does it seek to provide, a complete resolution to questions of forgotten history and historical trauma. Instead, we utilize art to ask questions, and we invite audiences to ask questions through and alongside the artworks. Since we have lost many historical texts, and we do not have direct memories of the Chinese railroad workers, we project the memory of these workers so that others might encounter them in the future. We hope that these works, and the larger project from which they are drawn (Yu 2025b) will provide both: (1) a platform for researchers interested in the U.S. Transcontinental Railroad to raise new questions; and (2) a framework for those who wish to use similar arts-based methods to explore diverse topics of migration and historical injustice. The study offers audiences different ways of thinking about the lost history and the stories of Chinese migrant railroad workers.

Visual art is a vital tool for research analysis, interpretation, and documentation. It breaks the spell of text-only scholarship, and it allows us to see and think in different ways. Artworks can be exhibited in galleries and conferences, opening research to wider audiences both publicly and academically (Leavy 2015). This project aims to synthesize different ways of knowing in order to learn, understand, and give voice to the untold lived experiences, hardships, and stories of Chinese workers who remain invisible and absent from many academic and historical studies. It is also about remembering –– and feeling deeply –– the lives of these forgotten laborers, whose stories were textured, multidimensional, colorful, and beautiful.

We dedicate ths project to the Chinese master railroad workers and builders –– to the great-grandfathers –– whose stories and names demand remembrance. We should never forget the generations who laid the foundation for our present. (Note: Throughout the article, the first person pronoun switches between ‘we’ and ‘I'. Whenever 'we' appears, it refers to both authors as a project team. Whenever 'I' appears, it signifies the role of first-author Haoqing Yu as the primary artist and project lead).

Do we know the names of dead railroad workers? Do we know where they are buried? Do we know what stories they told when they finally bored through the Summit Tunnel?

–– Hushka, Fishkin, & Wong 2017

Next >