Membran

zart spiralig gestreift

Beim Baden in die Haut

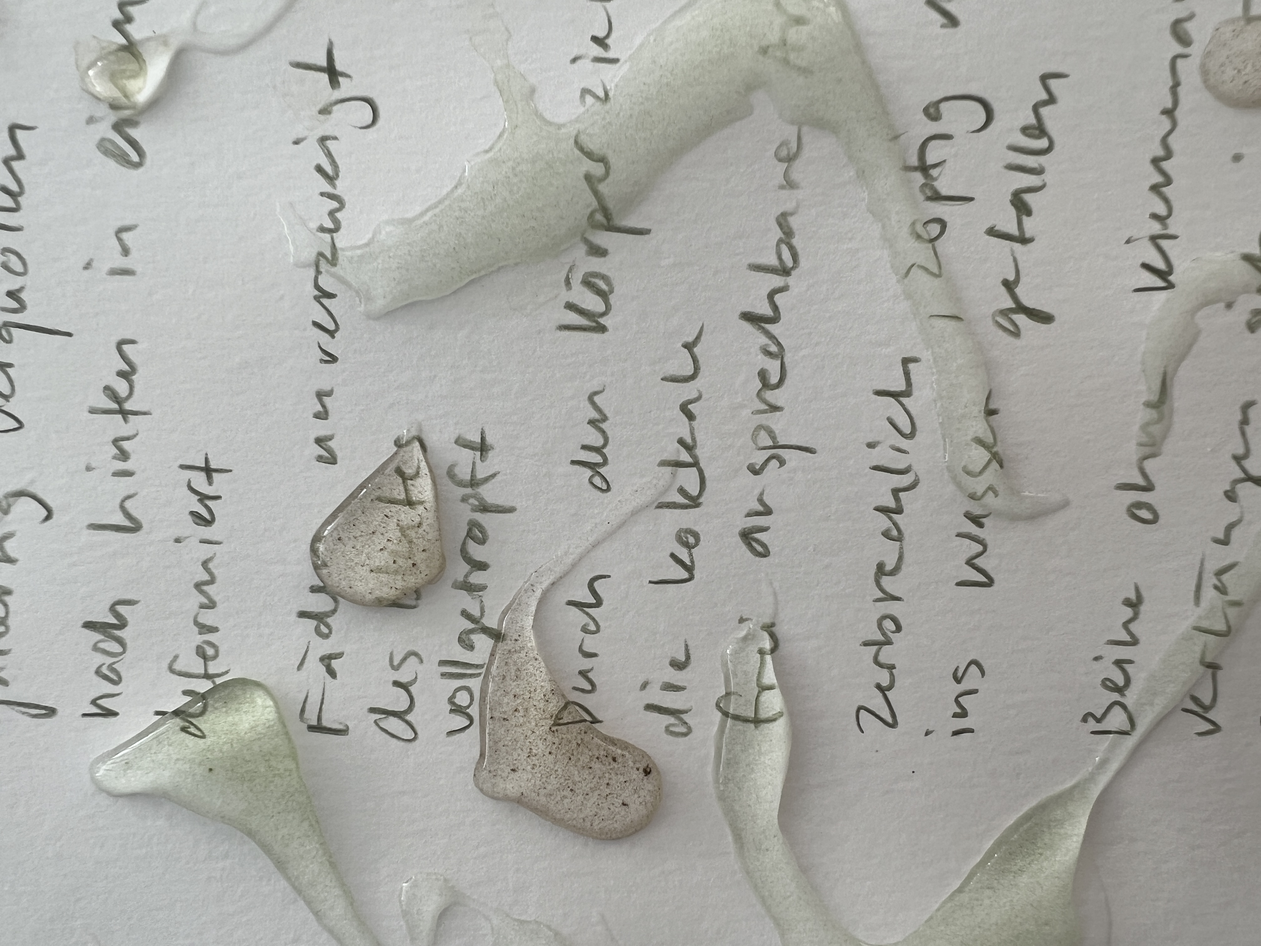

gallertig verquollen

nach hinten in einen Zipfel

deformiert

Fäden unverzweigt

des Blutes

vollgetropft

durch den Körper zieht

die kokkale

frei ansprechbare Art

zerbrechlich, zopfig verdreht

ins Wasser gefallen

Beine ohne Kiemenanhänge

verhängen sich im Fadengewirr

schwimmen langsam

spreizbar

oval bis eiförmig

in Bündeln gruppiert

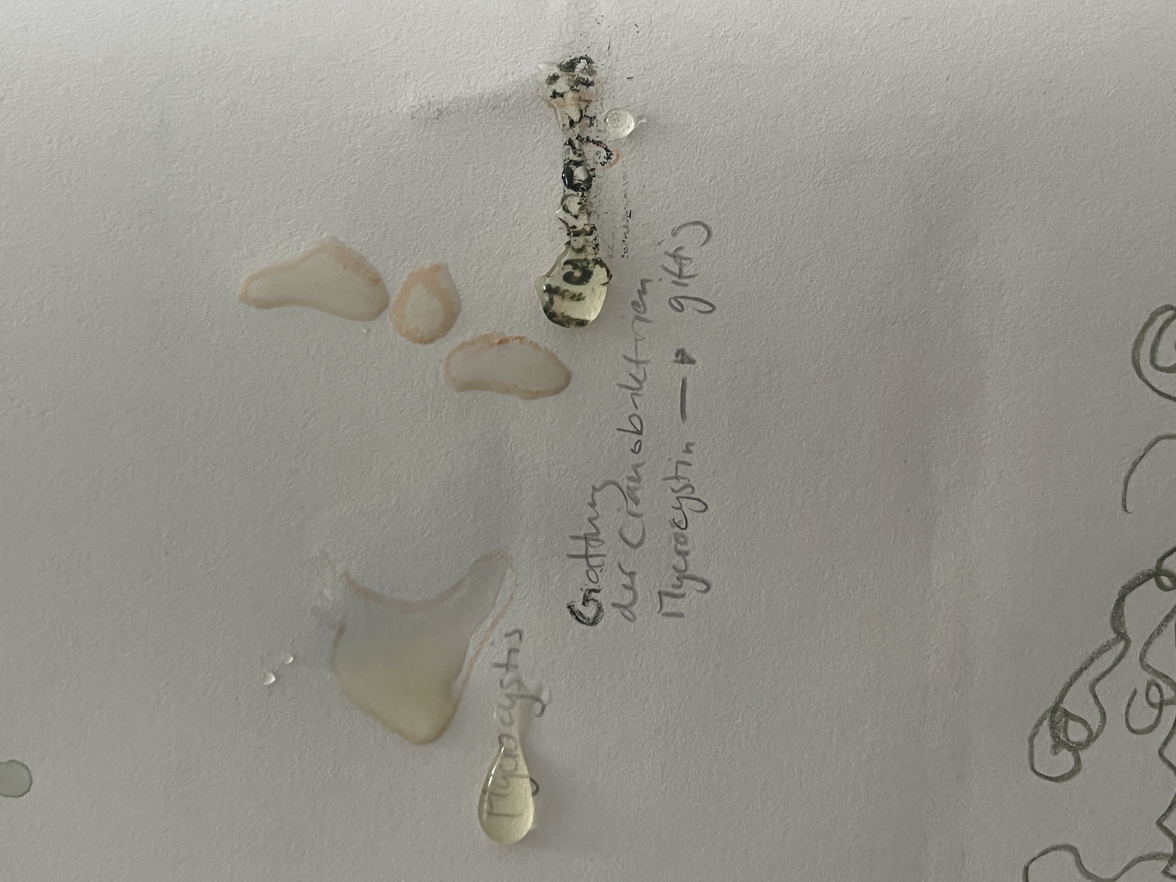

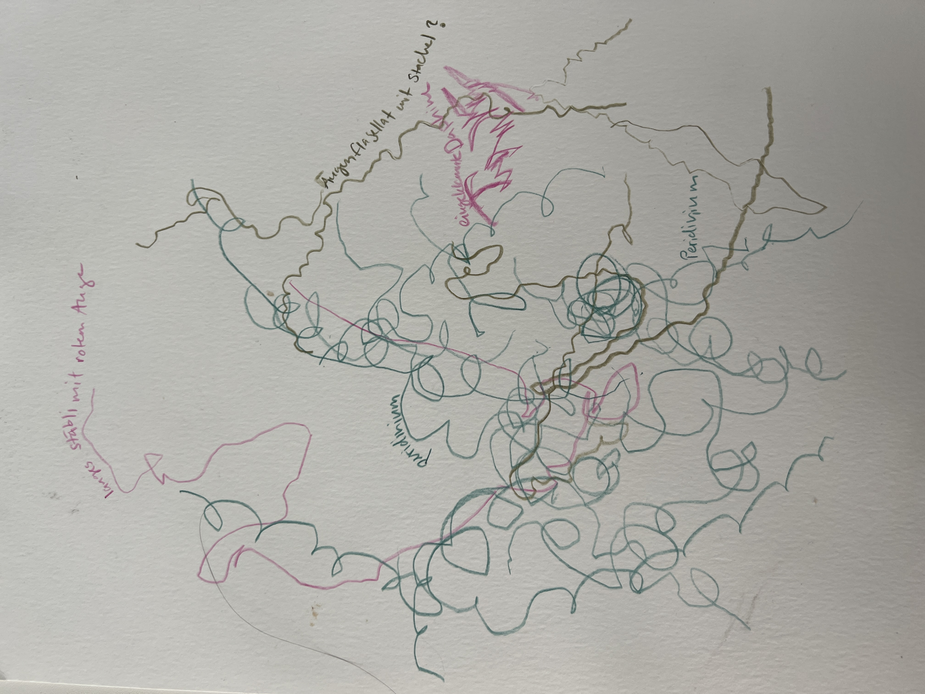

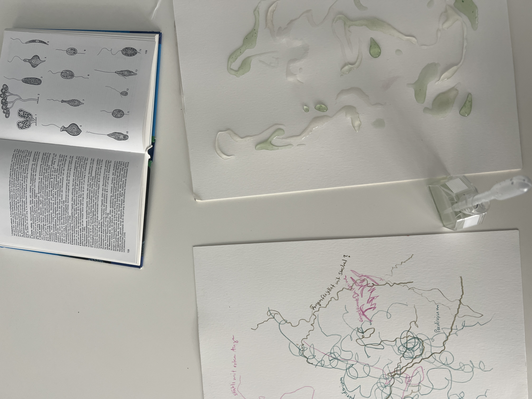

As a painter, I was equally fascinated by the movement, colors and shapes of plankton, and by the scientific tools that unveil a world normally hidden to the naked eye. I began experimenting with bacteria and algae on paper, using a pipette to drop water samples and letting them dry overnight, curious about the forms and colors they would leave behind.

In this process I explored the balance between control and letting go. I can influence the water only to a limited degree, and the outcome always surprises me.

What appears playful in this approach is in fact a form of research, an inquiry into how observation, chance, material and living beings interact. Just as in science, the results are already shaped by the tools and machines we use: the microscope, the pipette, the paper, the swirling movement of an alga. Each alters what we see and how we understand it.

While navigating the microscopic world of plankton, I encountered names, numbers and stories. The taxonomy books especially drew me in, revealing a vast diversity of organisms described in a language that was at once scientific and poetic. Many of the names seemed imaginative or mythic. One example is Nostoc, a cyanobacterium that carries many names related to the sky, as people once believed it came from above because it often appeared after heavy rainfalls. It has been called Himmelschnäuzer, Engelsschnäuzer or Himmelsgemüse. The scientific name Nostoc itself was invented by Paracelsus, derived from “nostril” or “Nasenloch,” since its appearance resembles snot. This movement of naming between heaven and snot reveals how scientific research not only follows facts but also creates narratives.