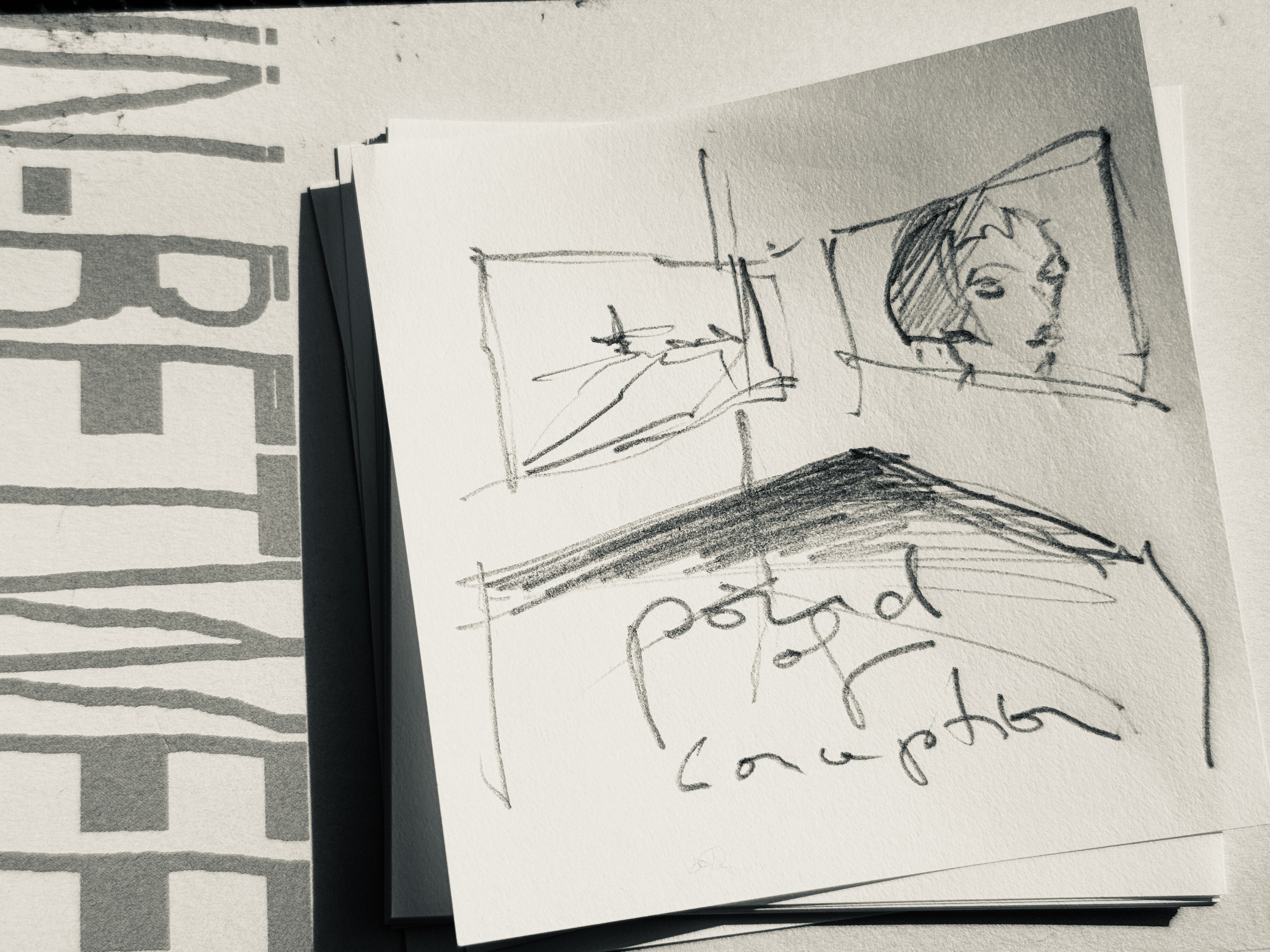

Drawing in the In-Between – ma, Intelligens and the Sketch&Draw Method

Drawing means entering an in-between space. It is neither mere representation nor pure invention, but a stance of openness to transform what is given into something new. What appears on the paper through the pencil is not only what lies before us, but also what is hidden “behind” the visible: a field of possibility that opens only in the creative process of drawing.

The fluttering line is not a line alone, but the trace of a searching act that creates the Japanese ma – not emptiness (white space), but the resonance space of the human being. In this in-between, the unexpected occurs: not the made, but the found. Serendipities, gifts of the moment, arising from what is there.

Drawing in the sense of Sketch&Draw is therefore less a mere act than a letting-happen-for-more. It is the art of staying open to what evolves from the movement of lines – in resonance with the cosmos of what is present.

The Drawer as Wanderer

Drawers do not control things. They are more like receptive wanderers embedded in a landscape, moving between world and memory, or between world and future. Every line drawn is an answer to a double call: from outside through perception, from inside through memory.

From a neuroscientific perspective, seeing is never mere registration. The brain works according to the principle of prediction: constantly comparing new stimuli with stored patterns. Karl Friston (2010) described this as the Free-Energy Principle – the brain continuously reduces the difference between expectation and perception.

In drawing, this process becomes visible: each line is a proposal by the brain of how the world might be. This proposal is immediately fed back into what the eye perceives anew. Thus a continuous dialogue arises between hypothesis (line) and reality (motif).

The richer the visual repository, the subtler this dialogue becomes. That is why it is essential for all who wish to be creative to expand this repository as much as possible. Studies by Gauthier and Tarr (2002) show that experts – birdwatchers or mechanics – perceive details invisible to laypeople: we see what we know. The same is true in drawing: the richer the visual archive, the more nuanced the resonance. Knowledge here does not mean fixation, but heightened openness for greater insights.

The hand is not merely an instrument but a thinking organ, closely linked to brain areas responsible for spatial thinking and even language (Goldin-Meadow, 2005). The hand “knows” something hidden from the eye: it gropes forward, finds rhythm, reacts to the pencil before the eye fully perceives the line. The hand is thus coupled to the brain before conscious perception sets in. This neurological difference is the decisive game changer in creativity. Genuine creativity is always connected to the pencil. Software interfaces can never achieve this due to neurological constraints.

Software places an interface in our way. It must first be cognitively processed. With the digital pen, technical latency intervenes. Both prevent the direct coupling of hand and eye. That is why hand drawing is fundamentally different from digital work. James and Engelhardt (2012) show that handwriting and hand drawing activate deeper neural networks than typing or drawing on screens. Digital devices introduce tiny latencies – milliseconds, imperceptible yet enough to disrupt the uninterrupted feedback loop of flow.

Here neuroscience meets psychology. Mihály Csíkszentmihályi (1990) described Flow as the state in which perception and action merge in seamless feedback. Flow arises only when feedback is immediate and unbroken – exactly what hand drawing enables. Sketch&Draw is therefore particularly conducive to flow: it demands attention yet remains accessible; it opens space for surprises without losing control. Flow is not a byproduct but the condition of knowledge.

Thus the drawer is a wanderer in the network of perception, memory, and movement. They traverse a field that only unfolds through their wandering.

Intelligens

The line in Sketch&Draw is not a finished contour but a vibrating space. Line bundles keep the form in suspension, open to multiple possibilities. They are not boundaries but transitions. In this the lines of Sketch&Draw resemble the Japanese ma: not marking an end but a productive in-between.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1964) emphasized that the visible always contains the invisible. Every line refers to more than it shows. The fluttering line makes this more perceptible: it not only depicts what is present but also opens a space in which the invisible may appear – a fact perhaps forgotten in recent decades of technology-driven culture.

Tim Ingold (2007) described the line as a “trace of life” – a process, not a product. In this sense, the line in Sketch&Draw is less a sign of something finished than a trace of becoming. Especially when drawn openly and fluttering in bundles, it oscillates and resonates.

When the line suddenly “tilts” and becomes form, when it gains pregnant significance, this is not merely the drawer’s decision. It is a gift of the cosmos of the present: form emerges because world, perception, and hand coincide for a moment. Here the concept of Intelligens can be invoked: a third principle, mediating between control and helplessness. In the fluttering line, Intelligens acts as a force that brings perception, memory, and world into resonance.

Thus the line is not only expression of the subject, but medium of a larger whole – a philosophy of the in-between.

Viewing and Perceiving – Dialogue without Latency

Drawing is not only about setting lines but also about looking back. Each line calls the eye, searches for form; each movement of the hand changes perception and influences what is yet to be found. Viewing is therefore not a subsequent step but part of the process itself – a dialogue between hand and eye, mediated by the brain. This is where creativity emerges.

When a new line is drawn, it shifts what is seen. The eye now sees differently: sharpened, directed, open to new aspects, facets, perspectives, and details. The gaze responds to the line just as the line responded to the gaze. This constant back-and-forth is crucial: often the eye remains fixed on the motif while the hand moves “blindly” on the paper – uncontrolled, so as not to interrupt the flow.

Neurologically, this interplay is remarkable. The hand is not guided by the eye; both access the same stream of perception and memory in parallel. This explains the immediacy of hand drawing: perception and action form a closed loop. Digital media, by contrast, fragment this loop through small but perceptible latencies (Oviatt, 2013).

Thus viewing is not passive. It is an active form of co-creation. The gaze opens the in-between where the line can work. In Japanese aesthetics, this corresponds to ma: not emptiness but tension, not nothingness but possibility.

Drawing as Process of Knowledge – Slow Emergence

Knowledge in drawing is not a sudden flash. It is a slow emergence, where lines, perception, and memory weave a fabric over time.

This growth can be compared to a meadow ecosystem. On such a meadow, factors such as light, moisture, or soil pH determine which plants may grow. But which species actually thrive only becomes clear over time. The meadow does not “decide”; it lets blooming arise in a complex interplay.

So it is with drawing. Perception, memory, attention, and hand movement are the conditions that sustain the process. But what form emerges cannot be predicted. It arises slowly, until suddenly a coherence appears that had not been conceived before.

Drawing is thus an ecology of knowledge. Insight does not come from a single act, but from the interaction of many factors. Each line, each gaze, each pause contributes – just as every plant has its place in an ecosystem. Only in their interplay does the whole become visible.

What emerges here can be called Intelligens. It is neither the product of an individual subject nor a mere natural occurrence. It is a third principle arising in the in-between, in dialogue between human, world, and line.

Thus, in the end, drawing in the sense of Sketch&Draw is more than technique. It is a form of knowledge that owes itself to the in-between – knowledge that grows slowly like a meadow: unplannable, yet not random; grown, yet not determined.

Glossary

• ma (間): Japanese concept of in-between space; not emptiness, but productive relationality (cf. white space, negative space).

• Intelligens: A third principle between control and helplessness; here understood as the creative force of the in-between.

• Serendipity: An unexpected discovery arising from openness and contingency, without being actively sought.

• Flow: Psychological state of deep immersion (Csíkszentmihályi), where action and perception seamlessly merge.

• Predictive Coding: Neuroscientific model (Friston) describing perception as the brain’s comparison of sensory input and expectation.

• Ecology of Knowledge: Metaphor for the interplay of perception, memory, attention, and action in the process of drawing.

References

• Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

• Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

• Gauthier, I., & Tarr, M. J. (2002). Unraveling mechanisms for expert object recognition: Bridging brain activity and behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 28(2), 431–446.

• Goldin-Meadow, S. (2005). Hearing gesture: How our hands help us think. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

• Ingold, T. (2007). Lines: A brief history. London: Routledge.

• James, K. H., & Engelhardt, L. (2012). The effects of handwriting experience on functional brain development in pre-literate children. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 1(1), 32–42.

• Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). The visible and the invisible. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

• Oviatt, S. (2013). The design of future educational interfaces. New York: Routledge.