On this bar, the microintervalic aspect of cante jondo is very present. It is also important the use of a B appoggiatura before the altered A sharp. This appoggiatura use is, as it was said, an Arabic feature present in cante jondo. While playing it should be remarked properly.

A similar cry and the intimate ending may be found in Falla´s La vida breve (1913), during a representation of a gypsy party (Audio example 7).

2. Manuel de Falla and the cante jondo

Cante jondo represents an important part of the Andalusian folklore. Nowadays, this term refers to a particular way of singing, very sentimental and intense (cante jondo derives to cante hondo, which literally means deep singing). The style is now part of Flamenco style, which contains a lot of “palos” (word used to define the different style, character, accompaniment or structure of a song).

At the beginning of 19th century, there was a great controversy about what cante jondo is. On the one hand, Felipe Pedrell (1841-1922), in Diccionario técnico de la música (1894), writes “cantos or cantes flamencos” as a general group of singing styles. Pedrell make then a big generalization with the andalusian chant:

On the contrary, Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) did not recognize all the diferent “palos” as real cante jondo. The above is clearly demonstrated by the very first rule of the first Cante jondo competition, (wrote by Falla himself):

In the original text (in Spanish) a highly derogatory language can be appreciated when it makes reference to different flamenco styles.

There is no doubt, then, that the different characteristics of cante jondo should be analyzed in order to understand Falla´s music.

To begin with, Falla´s interest in this music does not come from 1922 (year of the celebration of the Cante Jondo Competition). It was since his childhood, however, that Falla showed significant concern for this particular style. As pointed out by Laso de la Vega:

Besides, Falla was in touch with a number of cante jondo singers, the most well-known and influential was the father of his friend, the guitarist Angel Barrios. There is actual knowledge of the fact that Falla wrote numerous songs performed by this “cantaor”, and that he tried to translate them into notated music as well.5

2.1. Origins of cante jondo

There is a big debate over the origins of cante jondo as well as on the real influence of different cultures on it. As it was claimed by Alfredo Arrebola (1935-), one thing is certain; cante jondo does not come from one culture exclusively, but from the combination of quite a few styles and chants.. 6

First of all, it is worth considering Manuel de Falla´s personal opinion, as he will be the most important source for this research. Falla, as Felipe Pedrell, considers that the byzantine chant is a clear antecedent of cante jondo.

As it was expressed by Orozco, gypsies attached different topics and lyrics that would be present in a number of flamenco songs: sadness, pain, love and death.7

Thus, some of these characteristics may be found in Nights in the Spanish Gardens. The use of syllabic melodies and Greek modes will be also studied in relation to Debussy´s music. Apart from that, there are several particularities of cante jondo in the piece.

2.2. Characteristics of cante jondo

Taking into account the different characteristics and peculiarities of cante jondo is crucial to properly perform Manuel de Falla´s music. The singing of cante jondo is very particular and should be perfectly understood in order to emphasize the difference between it and conventional singing. This was evidenced by Falla himself, in the rules of the Cante Jondo Competition:

Fortunately, Falla put in writing his personal thoughts concerning the features of cante jondo. These are:

There is a fragment from a letter by Falla to Gatti-Casazza (1926) which deserved to be evaluated. This letter specifies how to perform a part of La Vida Breve which occurs during the performance of a cante jondo singer.

2.3. Cante jondo in Nights in the Spanish Gardens

In combination with the “guitarristic” and “Debussynian” parts, the ones of cante jondo create the characteristic sonority of the piece. Hence, the subsequent section analyzes the different cante jondo parts and its pianistic interpretation.

This analysis, thought, may represent a rather subjective approach. The differences between microtonal music and the western temperate scale make some of the cante jondo characteristics unrealizable. However, the piano approach to this particular way of singing always increases the level of the performance.

It would be advisable to note that in Nights in the Spanish Gardens (especially in the first movement), Falla makes a stylization of the Andalusian cante jondo, combining it with an impressionistic and romantic writing. It would be highly recommendable to listen to the last two examples in order to be aware of this stylization.

Once the different features of cante jondo written by Falla have been revised, the succeeding sections to be analyzed should contain at least one of the following characteristics:

- Small intervallic range (over a 6th).

- Cantabile and lyrical content.

- Characteristic ornamentation.

- Obsessive repetition of one note.

- Big and fast cadencial lines.

The French impressionism influence on the first piano intervention is evident. However, the cante jondo inspiration in the melody should be also noticed. A very common way to start a song by a cantaor is with just two or three notes after a guitar introduction. This guitar introduction is pointed by Falla in a letter to Ernest Ansermet, in which the composer gives some advices about the interpretation of the piece.

This first notes makes the singer aware of the tonality played by the guitar. It is also used to warm up. In audio example 1 from la niña de los peines we can appreciate this.

The use of a C double sharp (score example 1) remarks the microtonal intention of the passage, making that semitone interval very expressive. The use of a very specific range and the repetition of one note (D#) makes the inspiration obvious. The soloist should not play that notes clear; in fact both might sound together at some point. Besides, tempo may be flexible. However it is important to understand that the passage is a stylization of cante jondo and should be played in consecuense.

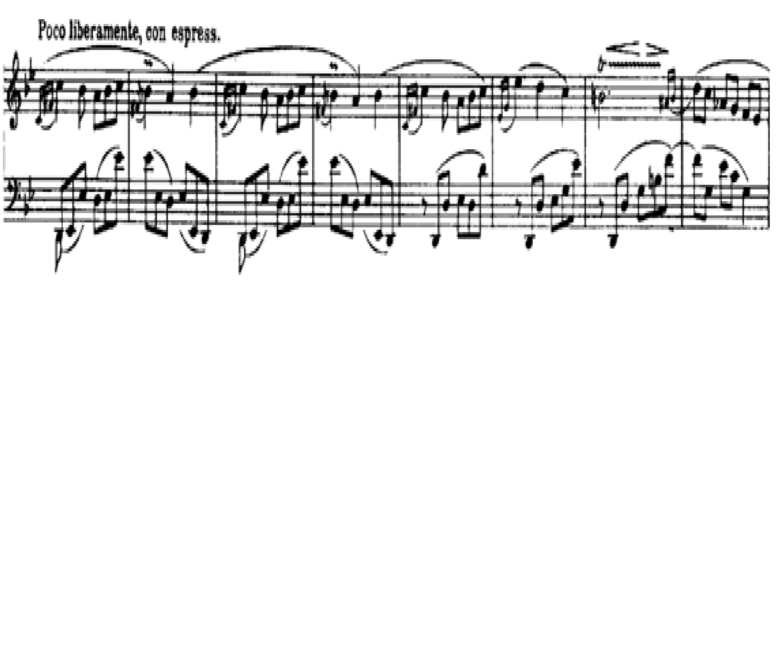

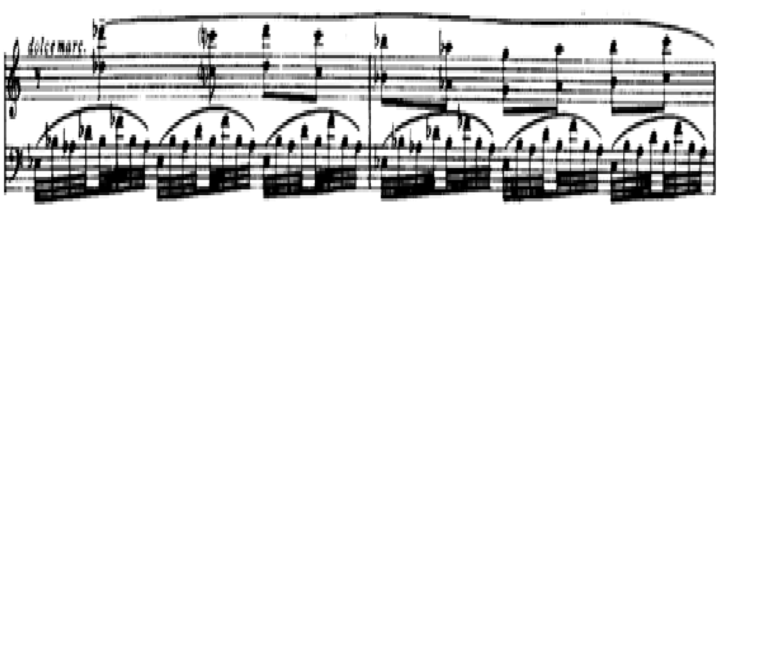

As it can be seen, the score example number 2 represents a melodic passage. It is developed within a range of 5th and insists in the note B. Falla also adds the “a tempo, ma flessibile” indication. In this case the microinterval characteristic would be very present in the interval of second between B and A. This should be played with a very close touch and with a non clear sound. As a result of this expressive first bar, the second should be played slightly faster. The characteristic obsessive repetition should be also marked by the pianist at every B.

The left accompaniment imitates a guitar, it is important to understand the natural resonance that would be created by the guitarist playing every bar with just one position. The dot on the E is just remarking the thumb attack on the lowest string of the instrument. The pedal should be hold at least until the third part of each bar. As if it was a guitarist accompanying a singer, the left hand must also be subordinated to the melody but with a rhythmic stability within his part.

In this case, finding a example in cante jondo is not that easy. However in the audio example 4 it can be apreciated the larger range of notes and the microtonal feature of the chant.

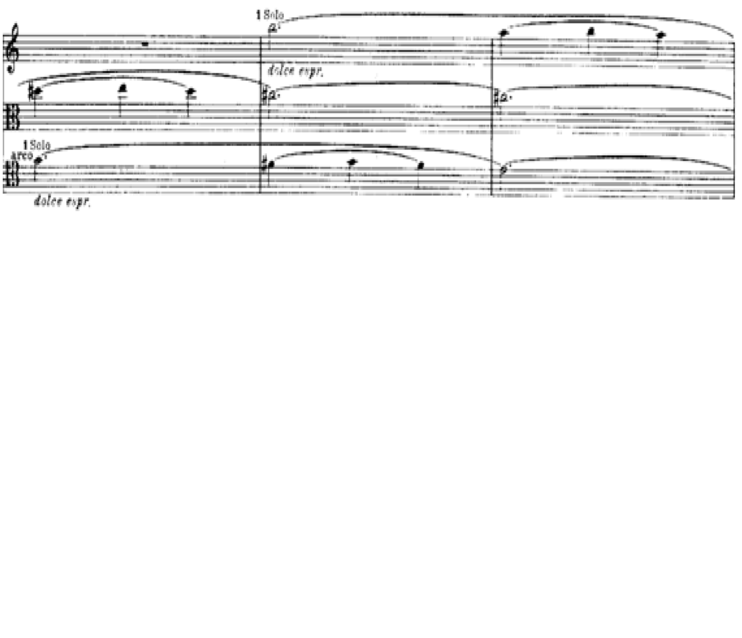

Despite not being a piano intervention, the dialogue between violin, viola and cello of score example 3 presents a clear cante jondo inspiration. In fact, it is the head of the rehearsal 10 motive.

In this case, the D sharp (in the case of the viola) may be played slightly out of tone, playing it higher and closer to the E, making after it a bigger interval between D and C. As it is advised by Falla, a quassi glissando between the notes is a characteristic mark of cante jondo and could also be used with moderation in some intervals.8 The audio example 5 is not itself microtonal, but there is no recording to be found.

Some bars after, the motive is played (in this case as originally) by the piano. The tension between the semitone intervals should be, again, felt by the pianist. This can be seen in score example 4.

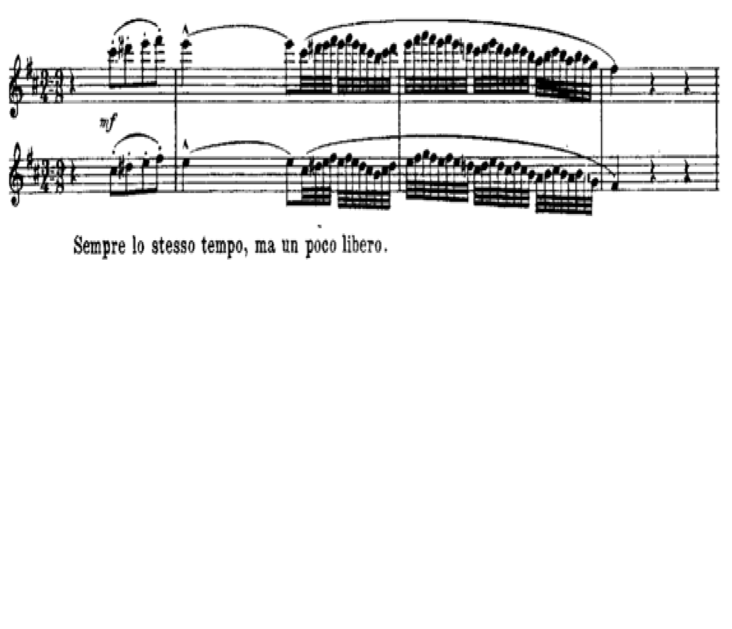

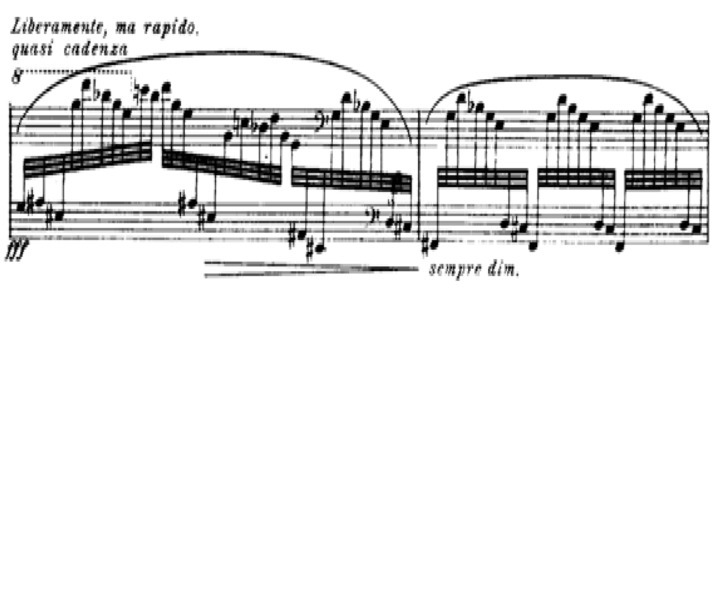

In this case, (Score example 5) the piano imitates a very common cante jondo cry. The cantaor expresses with a dramatic and violent voice a very sad, tragic or anguished emotion. It is completely syllabic and usually is done while crying “Ay”. In the piano the sound should be far from beautiful and must be violent and dramatic.

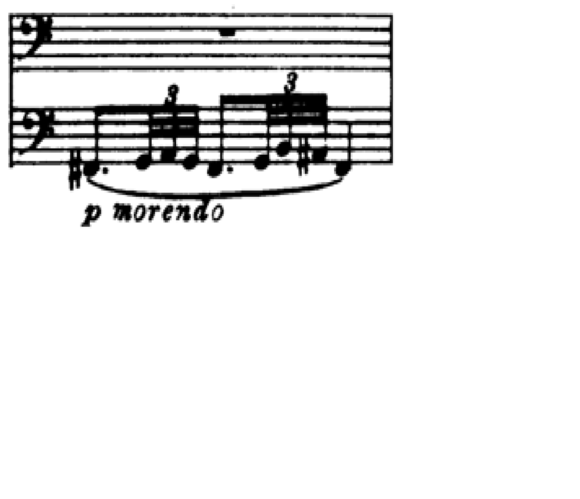

The energy and violence disappear quickly and the passage goes into a very intimate and meditative bar (Score example 6), which is characteristic of cante jondo style.

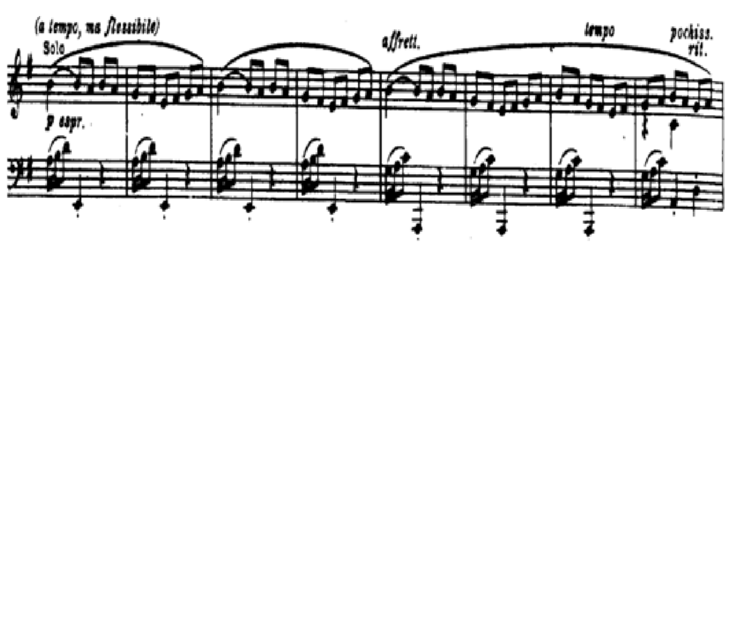

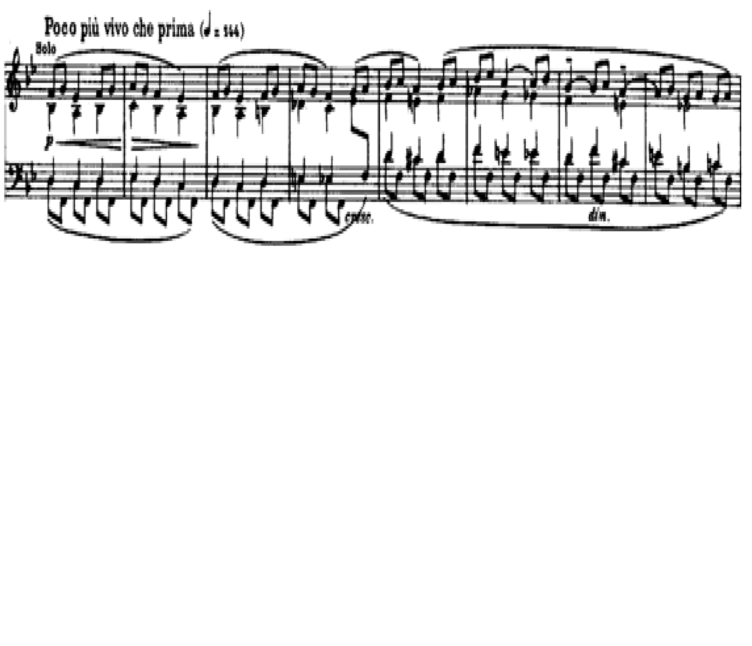

As in the previous examples, the passage of score example 7 presents a short interval range. In order to express the cante jondo freedom, the pianist should play with a flexible tempo and with a change of emotion (not only dynamic) at the crescendo bars.

In cante jondo it is also very common to present big contrast of emotion and intensity within a musical phrase.

In the passage of score example 8 the use of the accents at the beginning of the phrase are crucial. As it was pointed by Falla, the beginning of a motive contains with frequency one accent that leads the rest of the phrase.9 It should be played with violence and intensity by the pianist.

As it was said, the ornaments are also very important in cante jondo and must being considered as “extensive vocal inflexions rather than as ornamental turns”.10 The trill may be played in a singing way, feeling the interval between both notes.

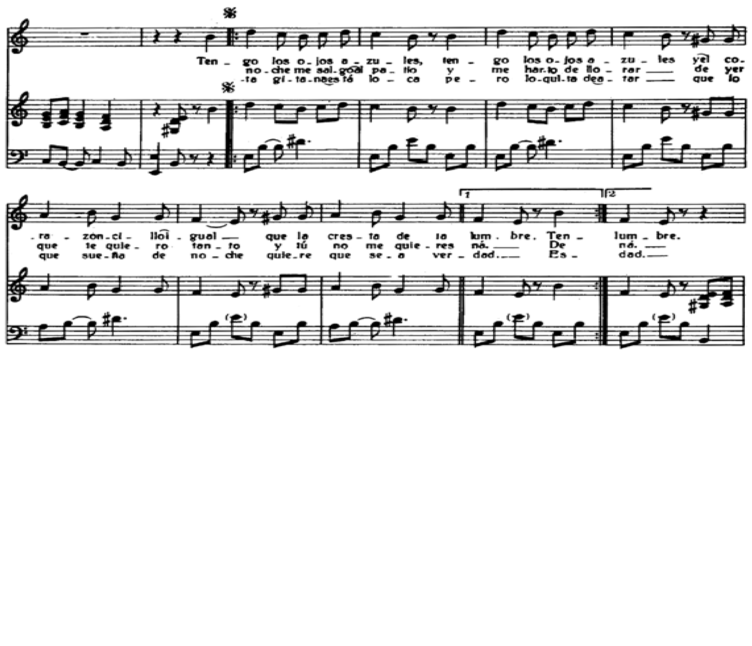

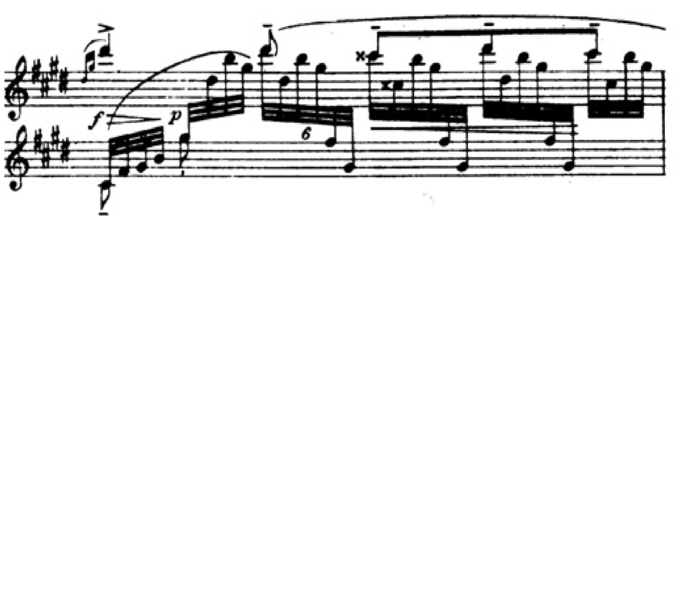

In this passage of score example 9 the syllabic and consonant feature of cante jondo can be clearly understood. The first two bars, with larger notes, are sung with normal lyrics; this makes clear differences between the accents at the beginning of a word. As it was said, for Falla the first accent is followed by quassi glissando notes. Of course the passage must be clear but the closest that a pianist can reach is, as Falla suggest, with the use of the pedal. This resonance may be combined with individual attacks, remarking every part of that hypothetic word.

On the other hand, the 16th´s of the third and fourth bars represent the melismatic end of the phrase, usually done with an “a”. In these cases it must be played with a big rubato, accelerando at the last part of the 4th bar. Again, the pedal should be held down at least half of the way.

The orchestra makes comments after every piano part. These comments are very typical from the “rondallas”, groups of string instruments that usually accompany vocal songs.

All this references can be understood listening to audio example 12 As in audio example 7, it is taken from Falla´s La Vida Breve. In the piece, an andalusian party with a cantaor and a rondalla is represented. Here, all the differences between words and melismas sung by the cantaor may been listen. It contains also the rondalla comments played by guitars.

This is the clearest passage with singing inspiration in Nights in the Spanish Gardens. Despite the comments about making music with folklorical inspiration but without taking directly real songs made by Falla, we can find some examples of popular songs in his music.

The first example comes from Piezas Españolas”(1906-09). In the third piece “Montañesa”, Falla uses a popular song from Aragon “La casa del señor cura” (The house of the priest).11

Zorongo is a popular song from Andalucia, which was transcribed by Federico Garcia Lorca in his book Canciones Españolas Antiguas (1961).12

The trascription of this song made by Lorca maintains some of the cante jondo characteristics, but is already more stylized. This is shown in audio example 14.

As it can be apreciated, cantaores sing this piece with different vocal modulations as well as the constant rubato within the phrase. In the case of Nights in the Spanish Gardens Falla represent that characteristics with the use of different ornaments as well of trills audio example 15. As it was said, the trill is a modulation of one note but made with the voice.

This piece is usually played with a stable rhythm and can be also danced. Rhithmic stability should be combined with the natural rubato referred above.

The popular melody becomes more and more lyrical until bar 152. This graduated transformation should be also taken into account by the performer and the orchestra.

In this second appearance of the "copla" material (score example 11), the impressionistic procedure of presenting the same thing at different moments of the day may be noticed. Now, the cante jondo is stylized. The orchestra part is no longer a clear accompaniment of the singer. The rhythm is not even and makes the sonority much more impressionistic. The general dynamics are also lower than the first time.

These aspects make the passage very different for the first one. It can be supposed that it should not be played with the same cante jondo resources mentioned above but with a more lyrical or classical touch.

In the audio example 10 from Juan Talega it can be apreciated the violence of cante jondo at its best.

The "audio example 13 shows how the same melody is performed by a cante jondo singer (Cristel Mora) with the characteristics of this primitive chant.

Cantos o cantes flamencos: consist in soleares, seguidillas, gitanas,

martinetes, serranas, polos, cañas, etc. 13

2nd act (1st scene): the voice of the singer should imitate the popular style without ever using the lyrical style. A little nasal voice, with quasi glissando ornaments, throwing them after an accent on the first note.14

For the purpuses of the competition, cante jondo will be considered to be the group of andalusian songs, the generic type of which we believe to be the so-called siguirilla gitana. This is the origin of other songs still kept up by the people, like the polos, the martinetes, the soleares, which thanks to their very high qualities, distinguish themselves within the great group of songs commonly called flamenco. Strictly speaking, though, this last name should be applied only to the modern group formed by the malagueñas, the granadinas and their common stock, the rondeñas) to the sevillanas, the peteneras, etc., all of which can only be considered as derivatives of those we formerly named, and will therefore be excluded from the competition

For qualification and award pupuses, the songs will be grouped as follows:

a)Siguirillas gitanas.

b)Serranas, polos cañas, soleares.

c)Songs without guitar accompaniment: martinetes-carceleras, tonás, livianas, saetas Viejas.15

In addition to the liturgical byzantine and arab elements, the siguirilla contains forms and characteristics that are somehow independent from the primitive sacred songs of the church and from the Moorish music of Granada. Where do they come from? In our opinion, they derive from the gipsy tribes who settled in Spain in the fifteenth century.

I remember that since his early years Falla felt a great enthusiasm for cante jondo: that manifestation of musical art, born from people´s soul. There, he searched for his inspiration and studied it with love. When he showed his talent as a composer, he tried to put in the score that harmonies and that sounds that he really loved.16

We would like to add that in one of the Andalusian songs, the siguiriya, which we believe best preserved the old spirit, we find elements of byzantine chant.17

Likewise, competitors should remember that it is an essential quality of the pure andalusian cante to avoid every suggestion of a concert or theatrical style. The competitor is not a singer, but a cantaor.18

At the beginning, the melodic line sur pont. The arp near the wood, to imitate the sonority of a guitar.19

a) The use of enharmonic intervals as a modulating means. “Modulating” is not used here in its modern sense (…). But the primitive Indian systems and those deriving from them do not consider that the places the smallest intervals occupy in the melodic series (i.e. the semitones of our tempered scale)- the scales- are invariable. In those systems the production of intervals that inhibit similar movements obey a rising or a lowering of the voice, which originates in the expression given to the sung word. (…) Moreover, each of the notes that could be altered was divided and subdivided, so that in certain cases the starting and finishing notes in some fragments of phrase were altered, which is exactly what happens in the cante jondo. To this we must add the frequent practice in Indian songs as well as in ours, of the vocal portamento, that is, the way of leading the voice so as to produce the infinite nuances existing between two joined or distant notes. (…) In summarizing this, we can affirm that in the cante jondo, as well as in the primitive eastern songs, the musical scale is a direct consequence of what we could call the oral scale. (…) What we now call “enharmonic modulation” can be considered, in a certain sense, as a consequence of the primitive enharmonic genre. Yet this consequence is apparent rather than real, because our tempered scale only allows us to change the tonal functions of a sound, whereas in the actual enharmonic process that sound is modified according to the natural needs of its attractive functions.

b) We recognize as peculiar to the cante jondo the usage of a melodic field that seldom surpasses the limits of a sixth. This sixth, of course, does not consist only of nine semitones, as in our tempered scale; through the use of enharmonic intervals, the number of sounds the singer can produce is substantially increased.

c) The repeated, even obsessive, use of one note, frequently accompanied by an upper or by a lower appoggiatura. (…) In certain songs of the group we are considering, (particularly in the siguirilla), this device permits the destruction of every feeling of metrical rhythm, and thus gives the impression of sung prose, although the text is in verse.

d) Although gipsy melody is rich in ornamental features, there are used only at certain moments –as they are in primitive oriental songs- to express states of relaxation or of rapture, suggested by the emotional force of the text. They have to be considered, therefore, as extensive vocal inflexions rather than as ornamental turns, although they sound like the latter when they are “translated” into the geometric intervals of the temperate scale.

e) The shouts with which our people encourage and incite the cantaores and tocaores also originate in a habit still to be observed in similar cases among the oriental races.20