Act four

Arrival

My arrival is the discovery of pleasure. It is finding something I did not know I wanted: an experience of belonging and receiving. When everything else keeps moving and changing, arrival is the capturing of a moment that makes sense and feels permanent for a while.

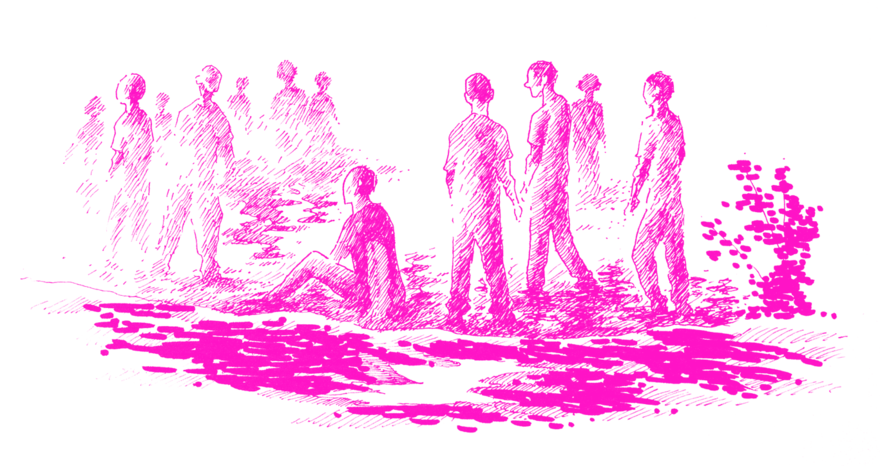

The title of this paper is Walking with Soldiers, not cadets. Cadets are soldiers, but ‘cadet’ sounds different from ‘soldier’. Words matter, and being a soldier connects a body to war. Soldiers are capable and willing to take life. Cadets train operational skills, which are "the desire and ability to win battles", as the University web page states. No other university than a military one will teach a student how to shoot a bazooka or drive a tank. But when I asked about killing, during the walk and in the following months, no cadet could identify with a potential killer. No loss, no war scars, no PTSD – not even as a possibility. Instead of soldiers, the cadets appeared to perceive themselves as 'citizens with a uniform'. Extraordinary citizens, yes, who can shoot a bazooka, drive a tank, guard a border, fly a Hornet, or strategise amphibious warfare. Yet, war (as an experience they are preparing for) seemed to be written off from their everyday military experience.

This ambiguity was tangible, bodily, sometimes a squirming, especially later in autumn when I conducted more interviews. The trouble we need to live with, then, is the pull between two seemingly distinct poles: soldier and civilian.

The imagined value of a military institution is built on fear of the not-yet, but familiar, and this requires the very exceptionalism which I began my struggle with. Exceptionalism which is presented in imageries of battle and weaponry, such as a recruitment video.

But when I walk, I have no such thoughts.

War endures in relation to and through their continual absence (Öberg 2016, 166).It was the absence of war which made a soldier invisible. Speaking of a soldier prepared to kill and to die, is to bring war from absence to awareness. To evoke the idea of a soldier is to bring to light a civilian. 'Civilian' is a category useless to me, unless it means 'non-military'. Alone, 'civilian' stands for nothing. I wonder, in war-time, would I still be a civilian?

The longer I stayed, the more I found myself capable of walking. I wanted to show my group I had the bodily capacity to march just like them. I was a trained body too, a regulated body. Militarisation is not only about ideas, values and priorities. It is also a process of bodily regulation (Macmillan 2011). Entrainment to common bodily rhythms and intensities is part of the emergence of friendship in a shared embodiment (McSorley 2016).