"Dovunque il guardo giro", Giovanni, in La Passionne di Gesu Cristo (1730)

Soprano: Lydia Teuscher, Orchestra: Capricornus Ensemble Stuttgart, Conductor & trombone: Henning Wiegräbe.

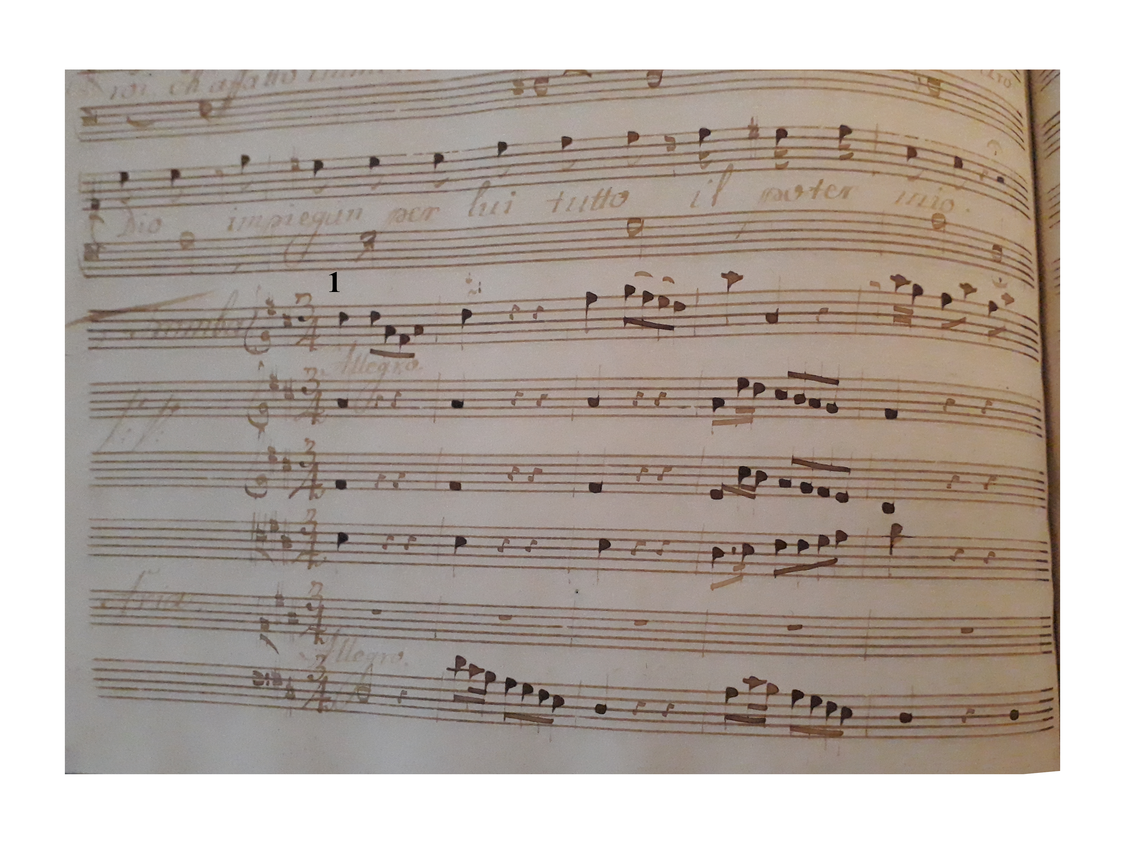

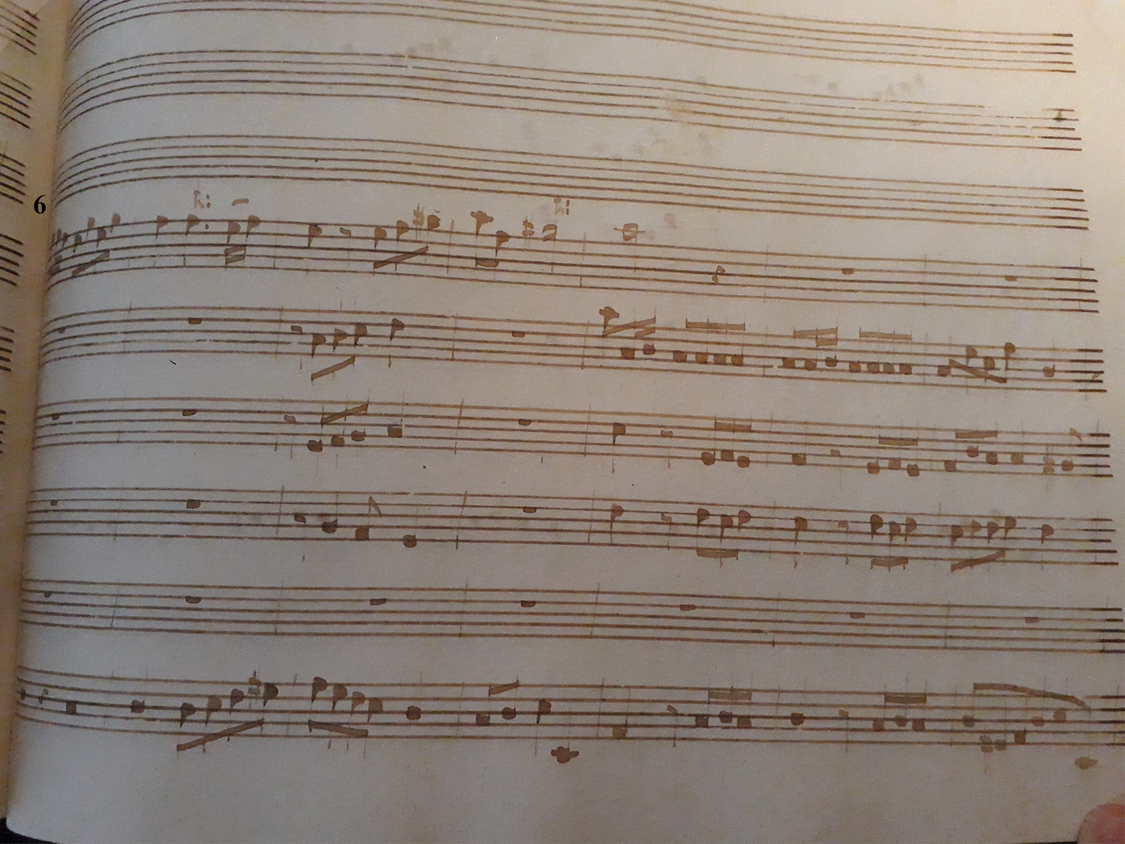

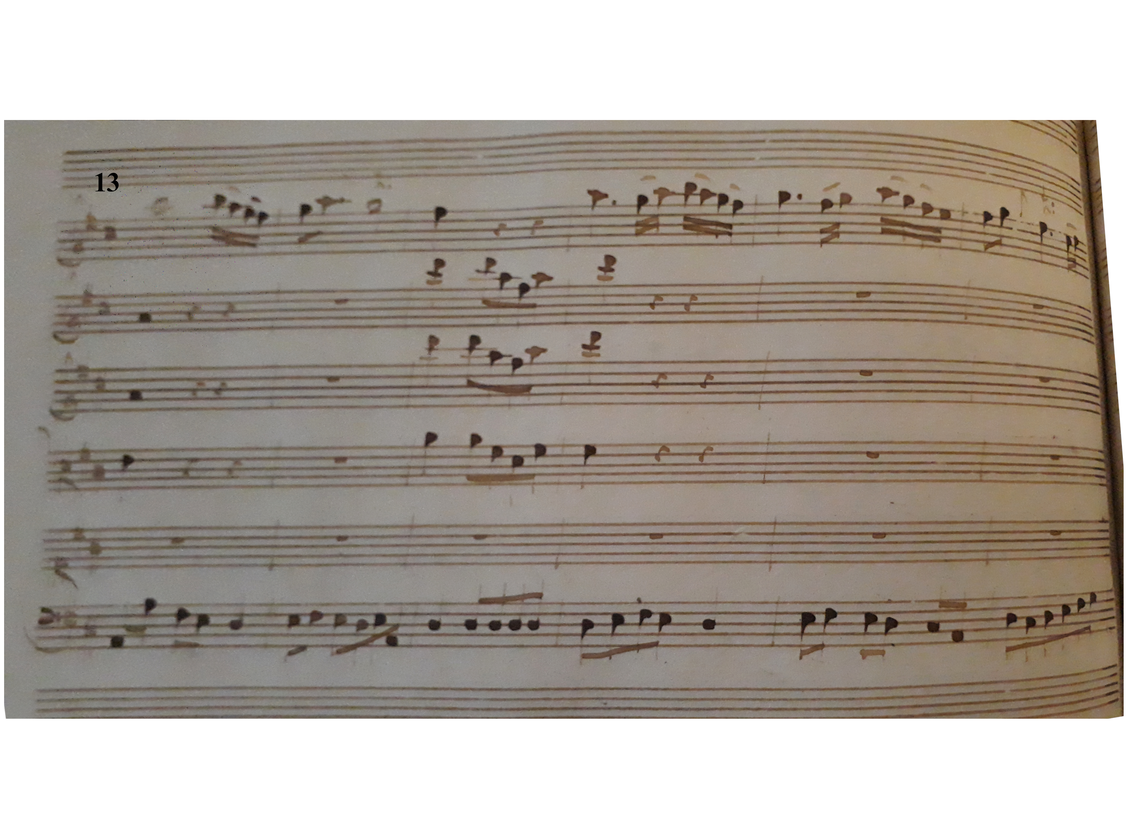

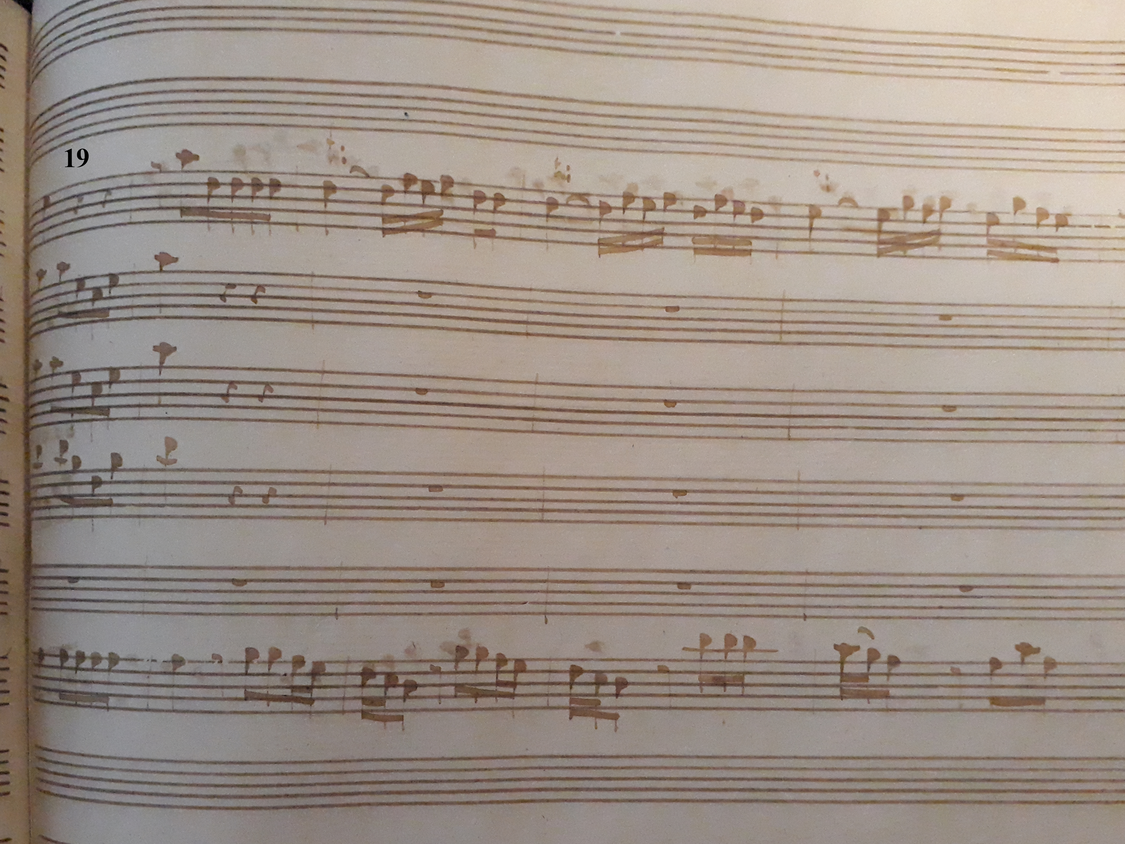

Prayer - analysed example: Eliacim

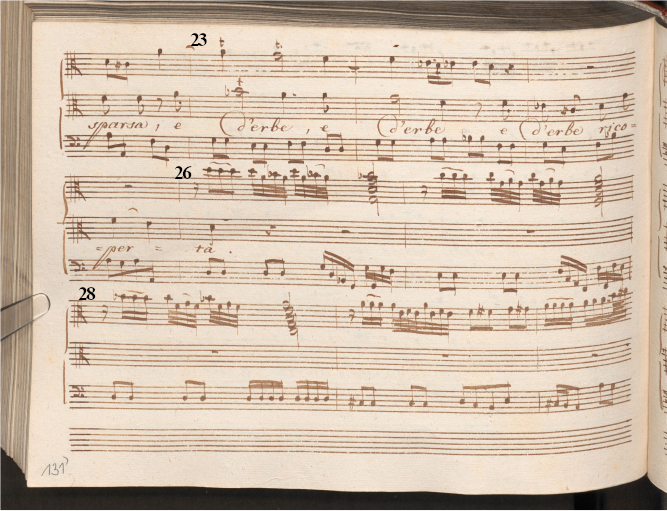

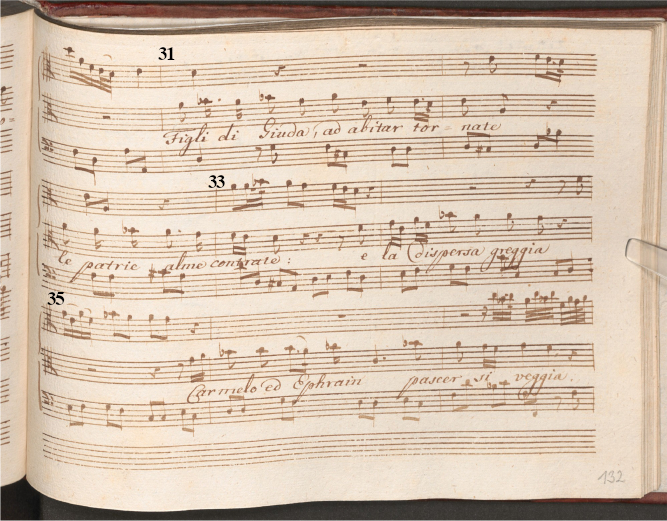

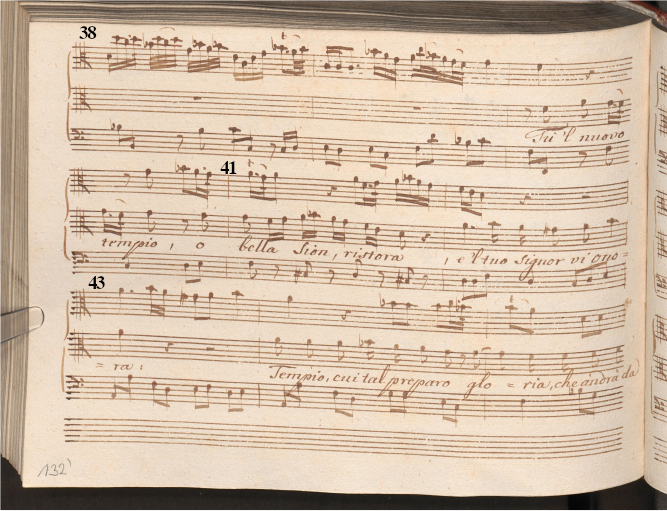

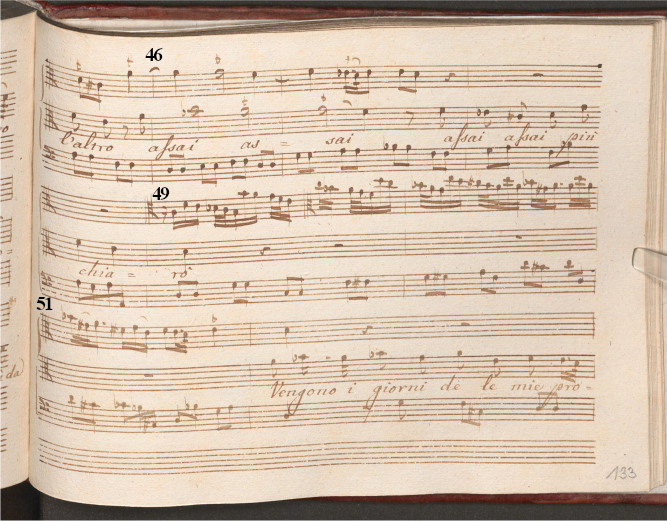

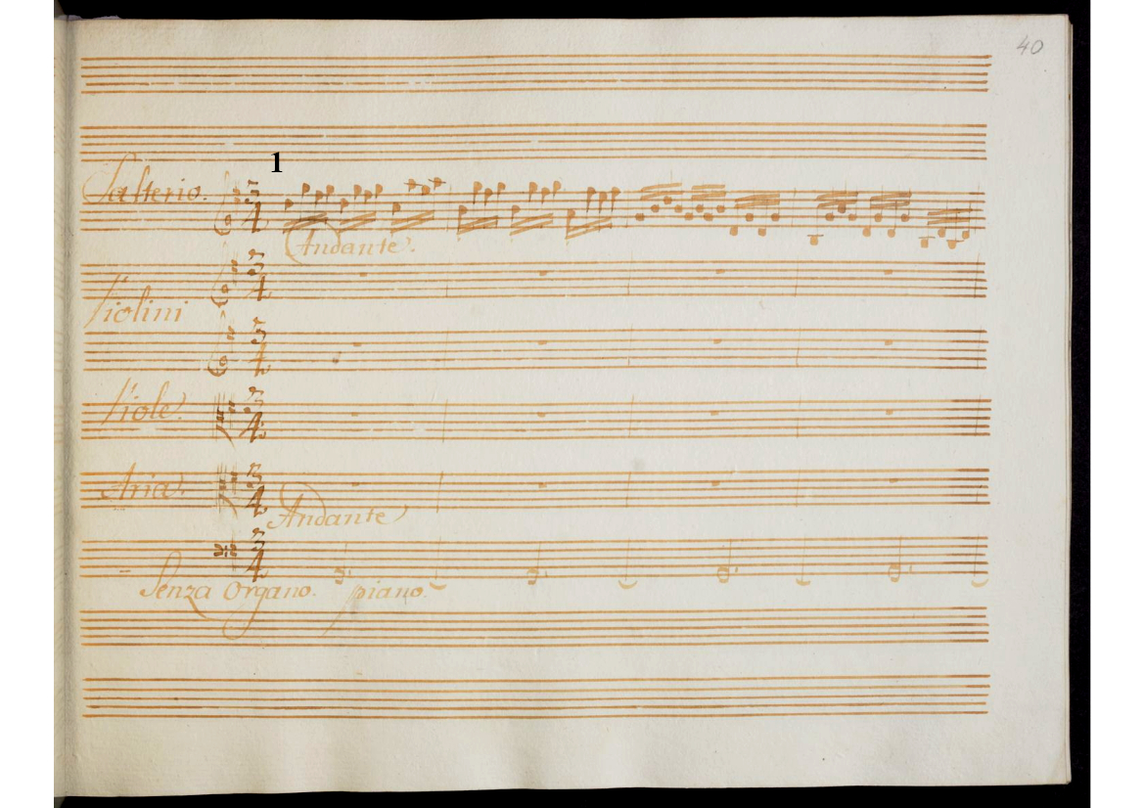

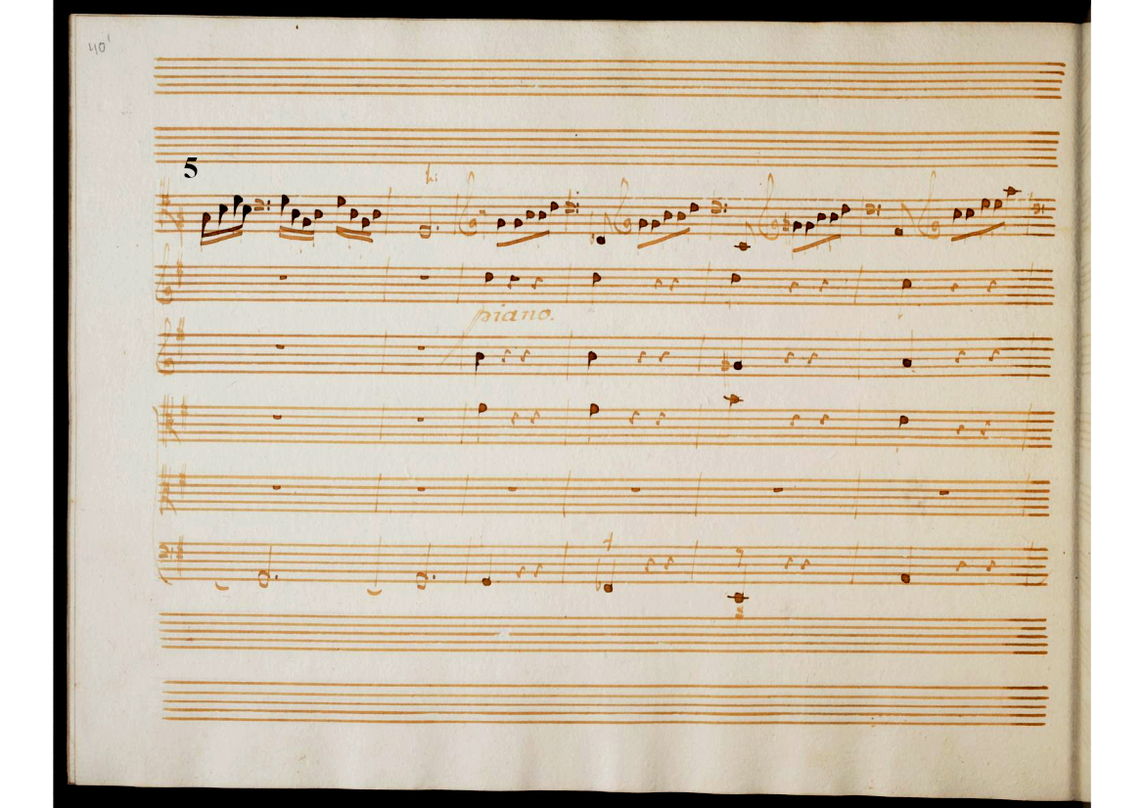

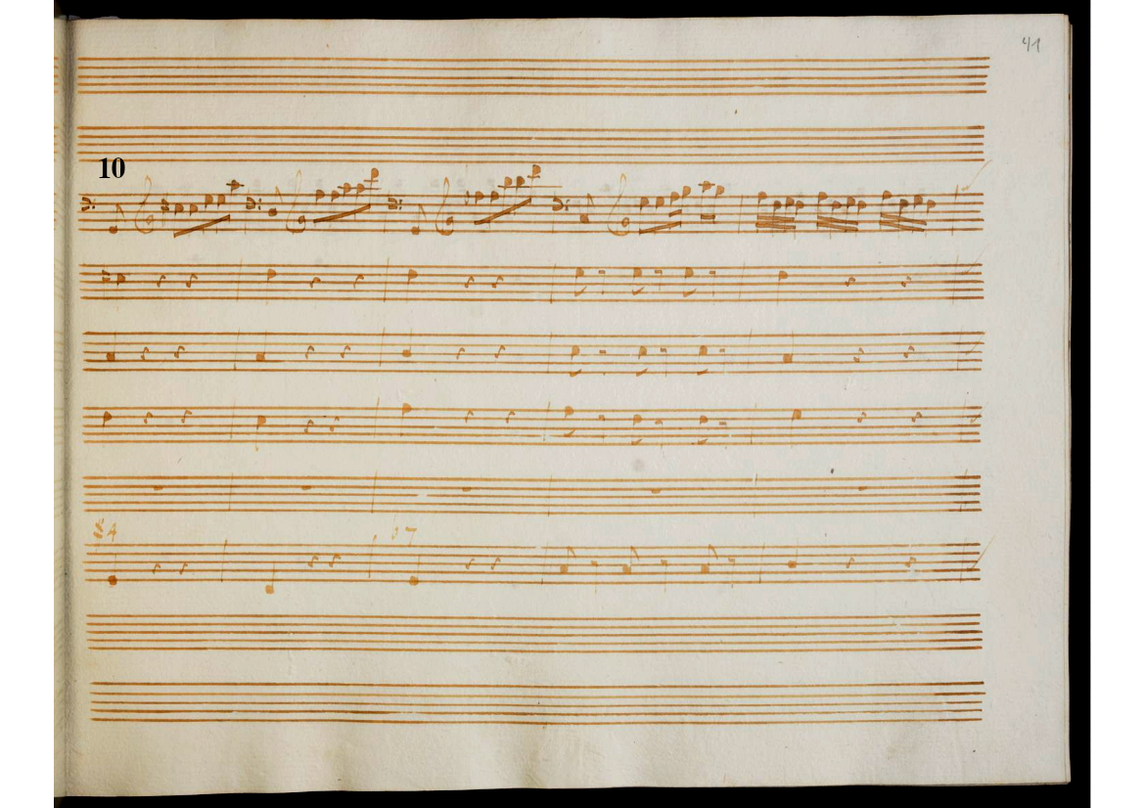

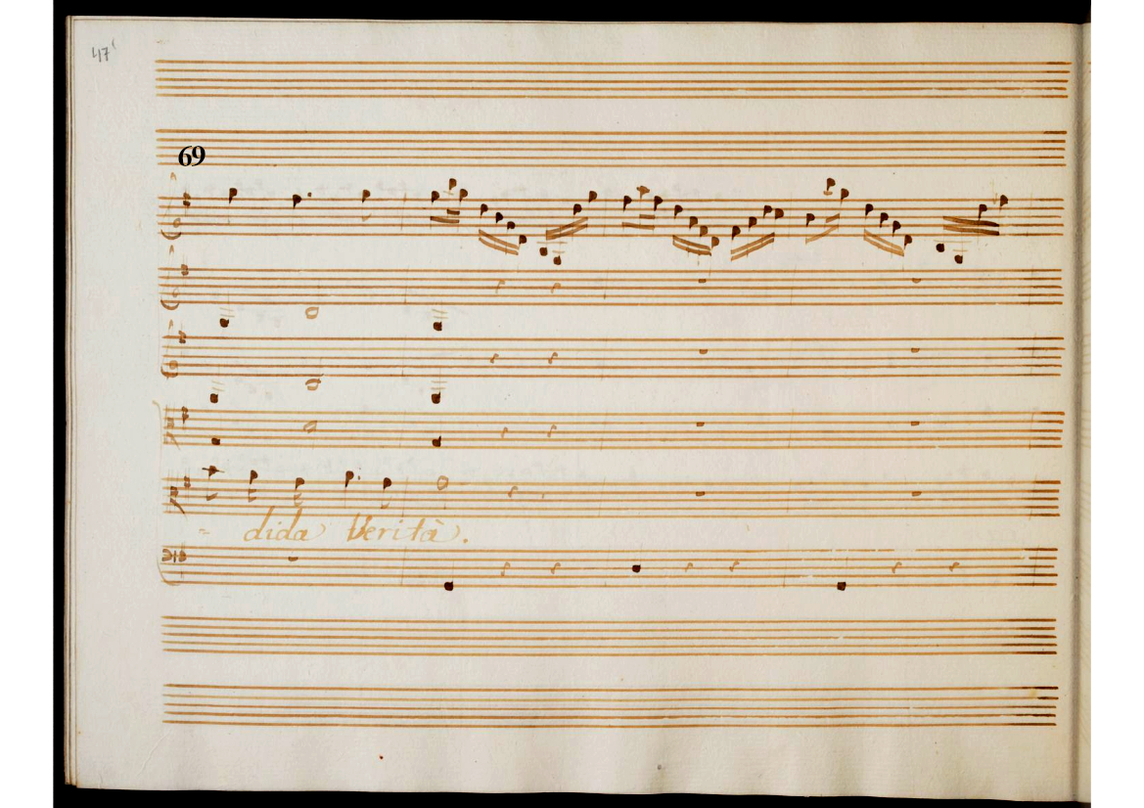

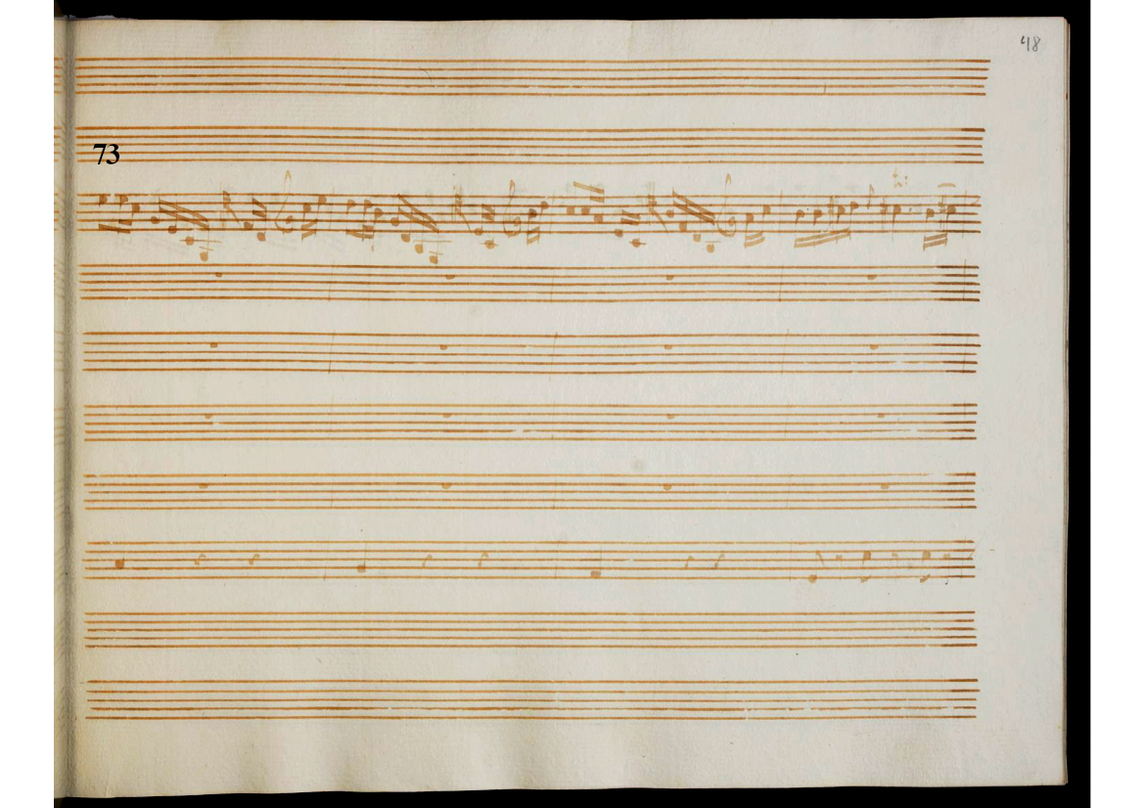

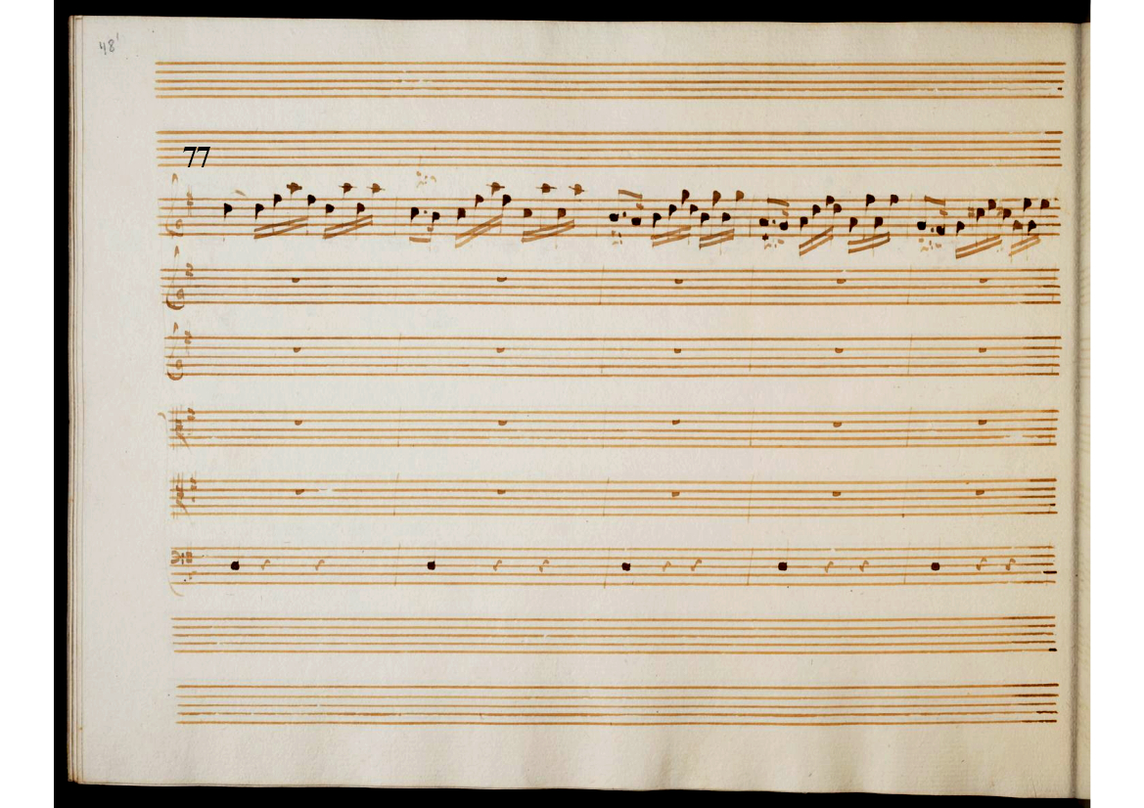

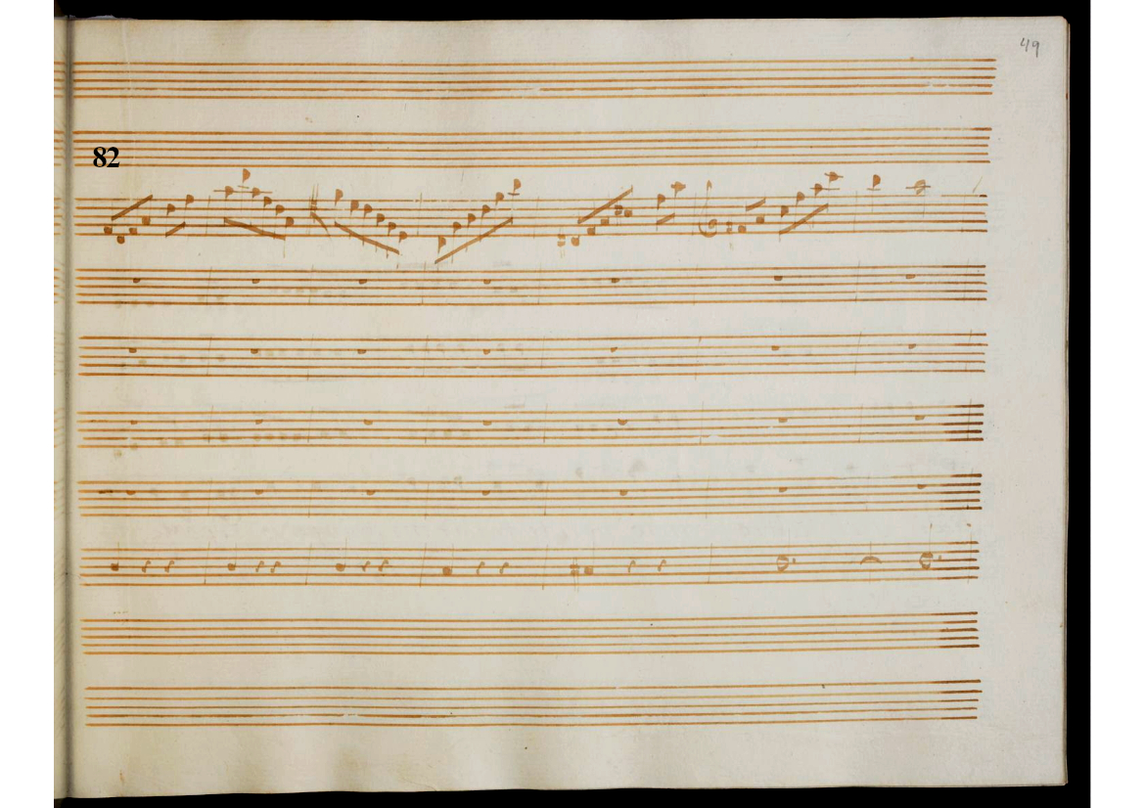

This aria from the oratorio Le Profezie evangeliche di Isaia is the first by Eliacim and the fifth aria of the first part.

Eliciam asks for God's support to maintain him in his choice to leave the service of Manasse, the tyrannical and ungodly king of Judea. He wants to follow the word of the prophet Isaiah who advises the queen to take better care of her son Manasse.

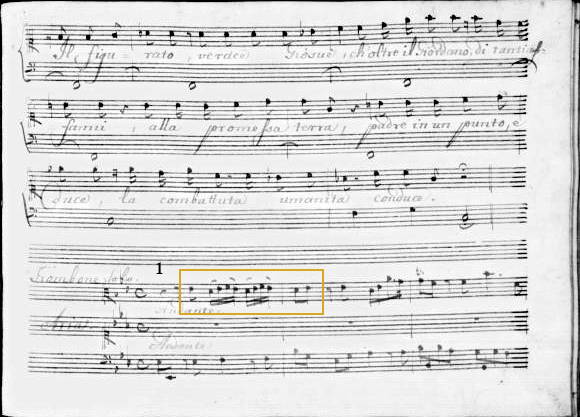

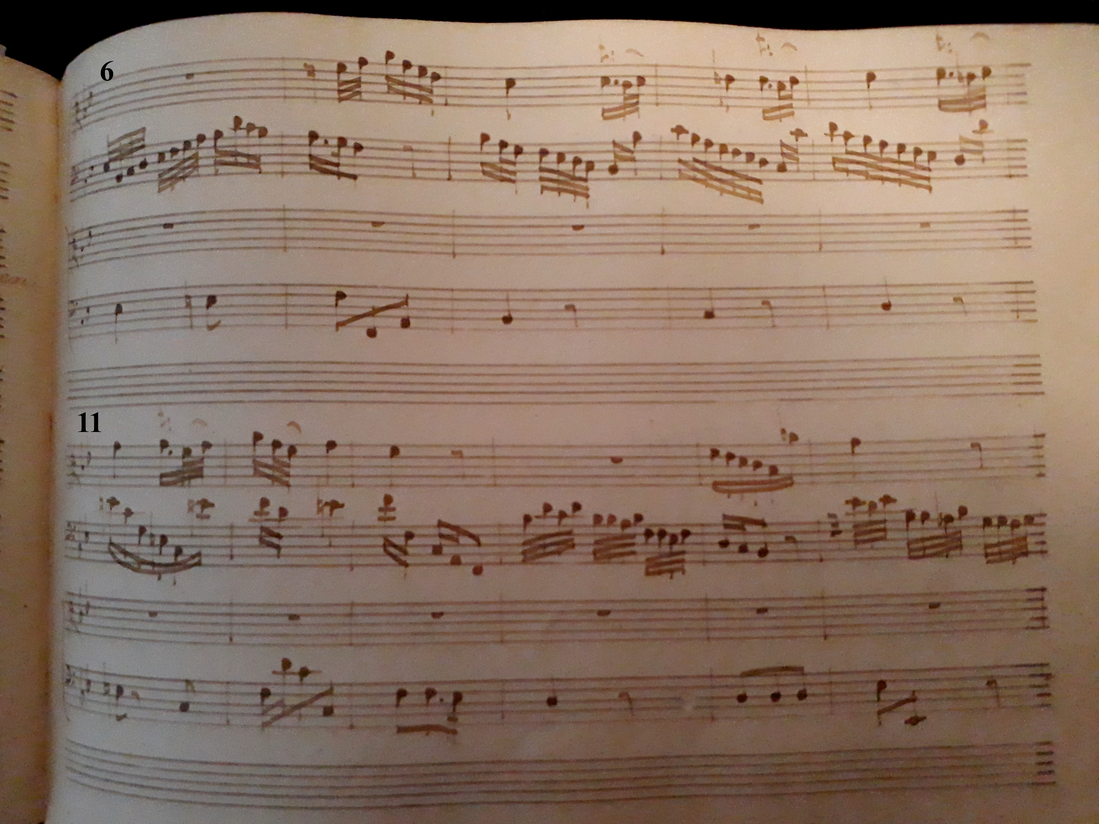

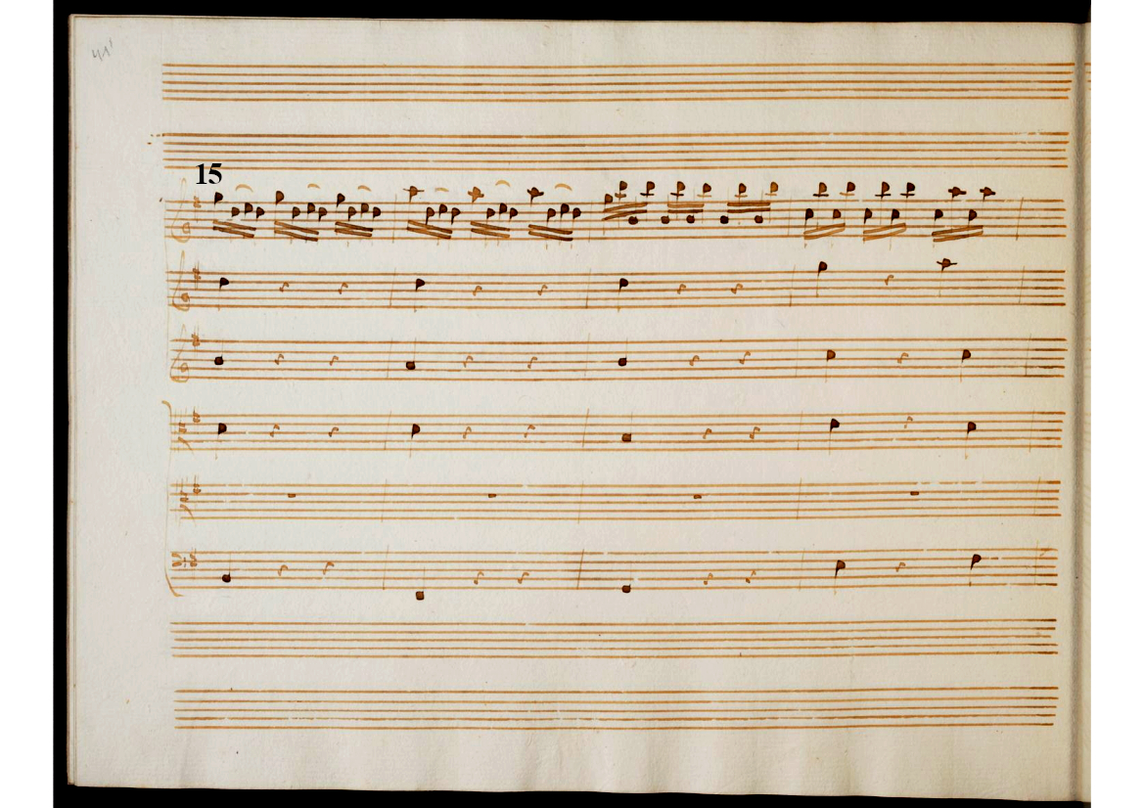

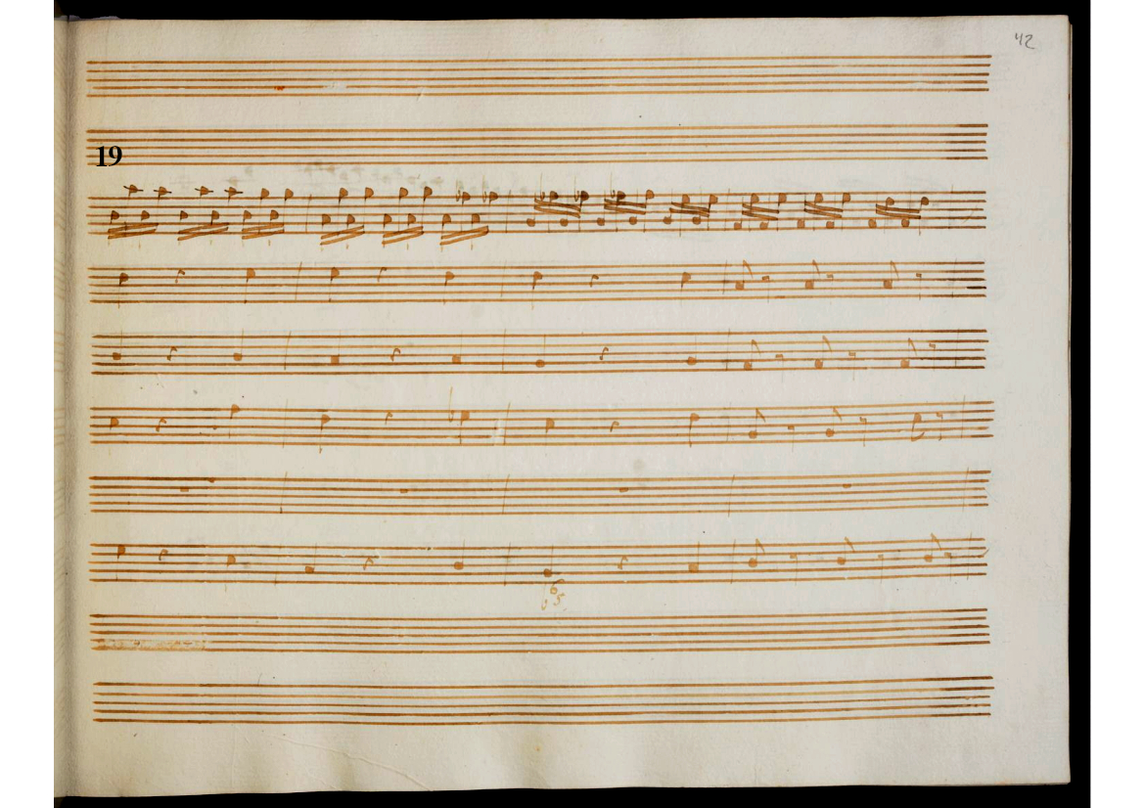

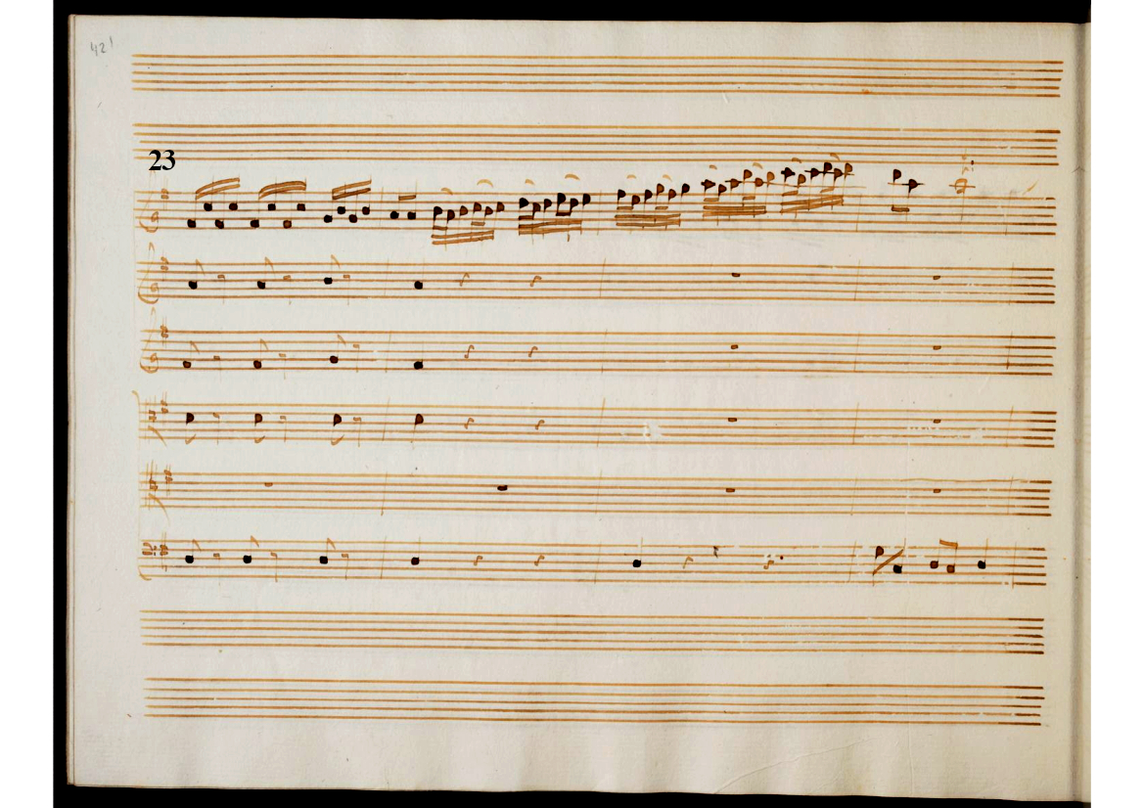

The aria is written for salterio, strings, alto voice and basso continuo(BC). It is in 3/4 and andante.

It begins with a free arpeggiated introduction to the salterio on a pedal of the BC on G.

The strings enter in chord form from bar 7 and the introduction to the salterio with the string chords lasts until bar 26, giving the listener plenty of time to immerse himself in the light, airy atmosphere of the salterio.

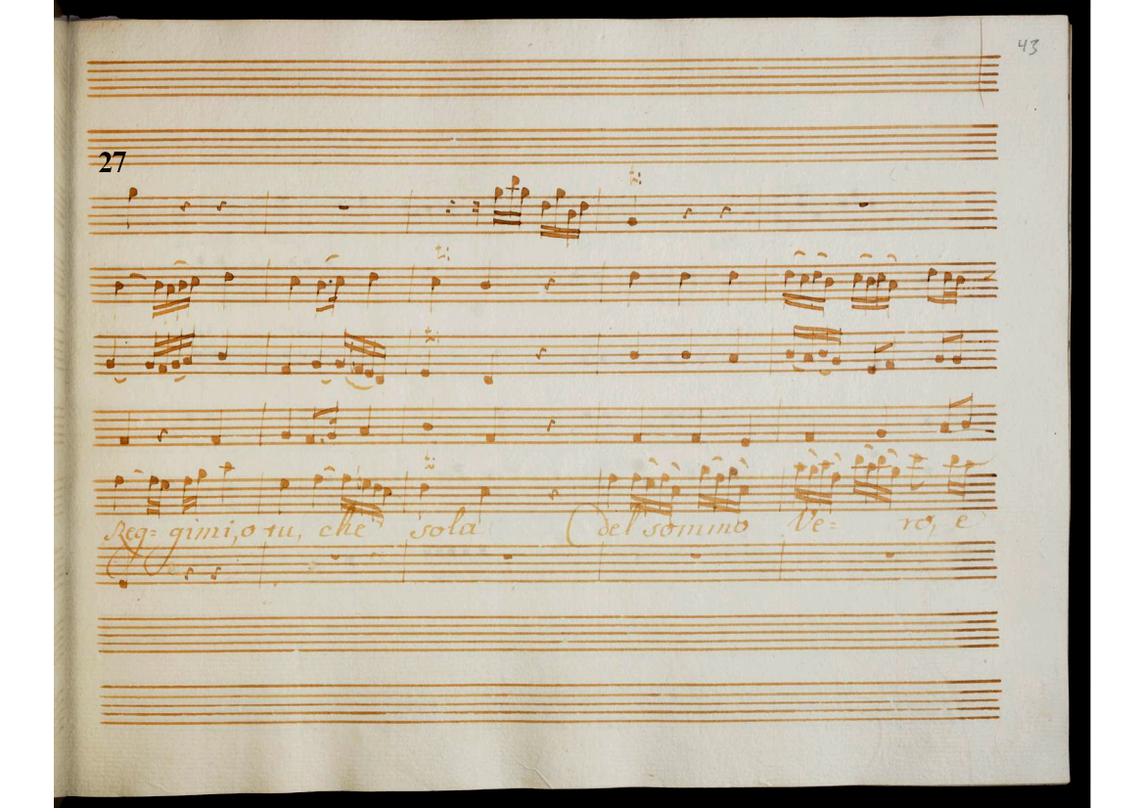

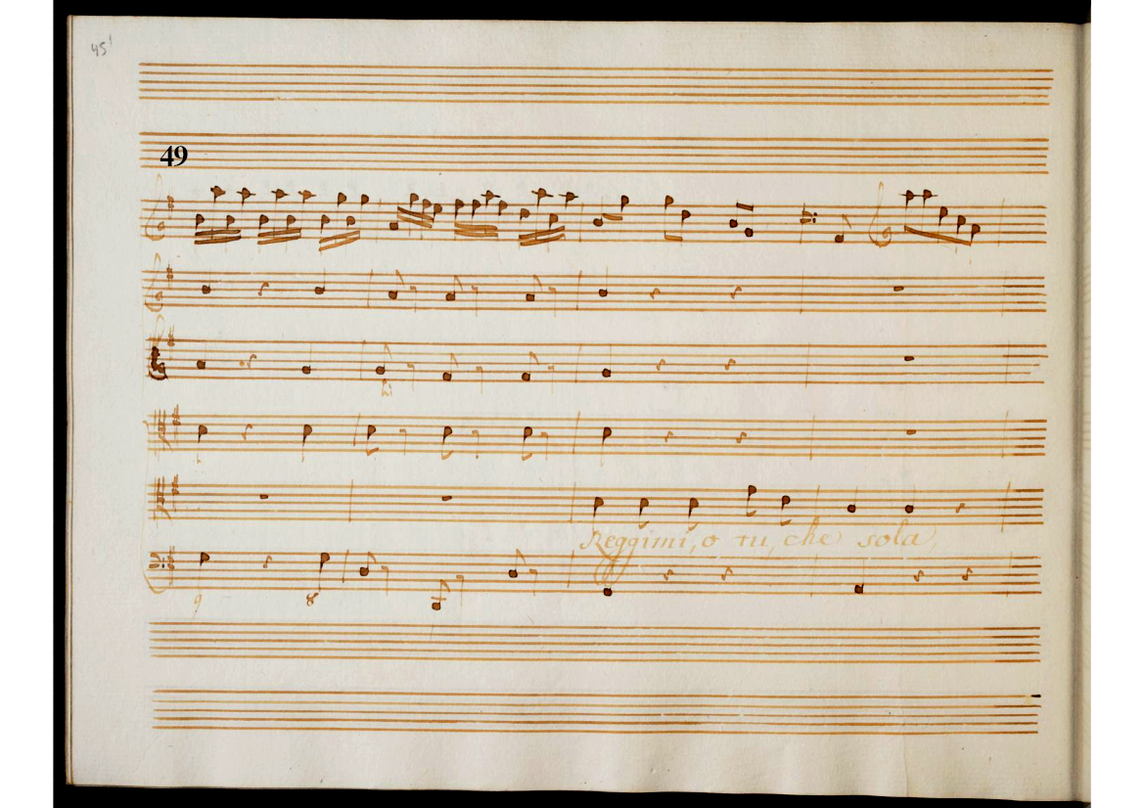

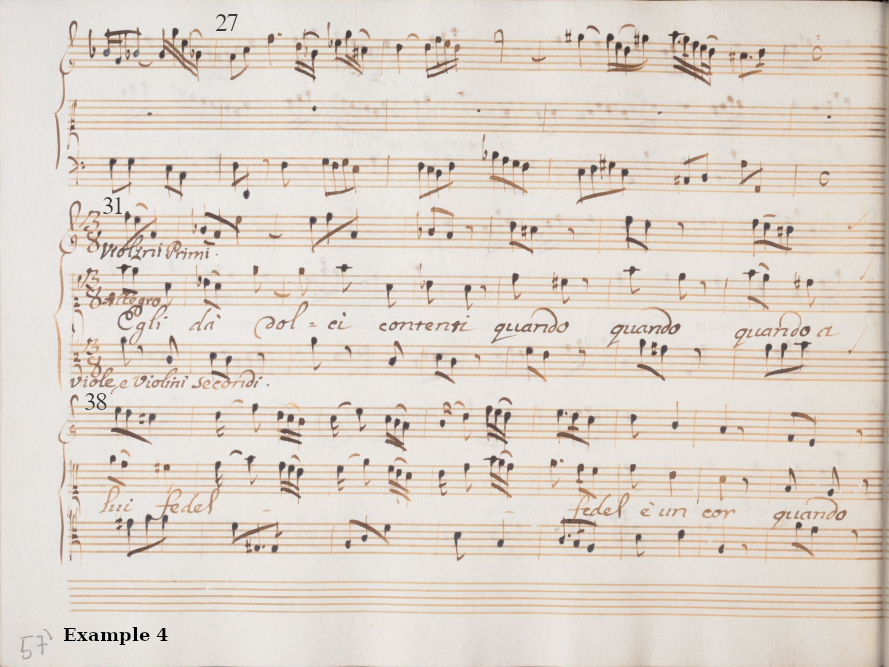

Eliacim begins to sing at bar 27, addressing God directly: "Reggimi, o tu" (sustain me, O you). He is accompanied by the strings and at each of these short pauses, the salterio is heard for a short moment.

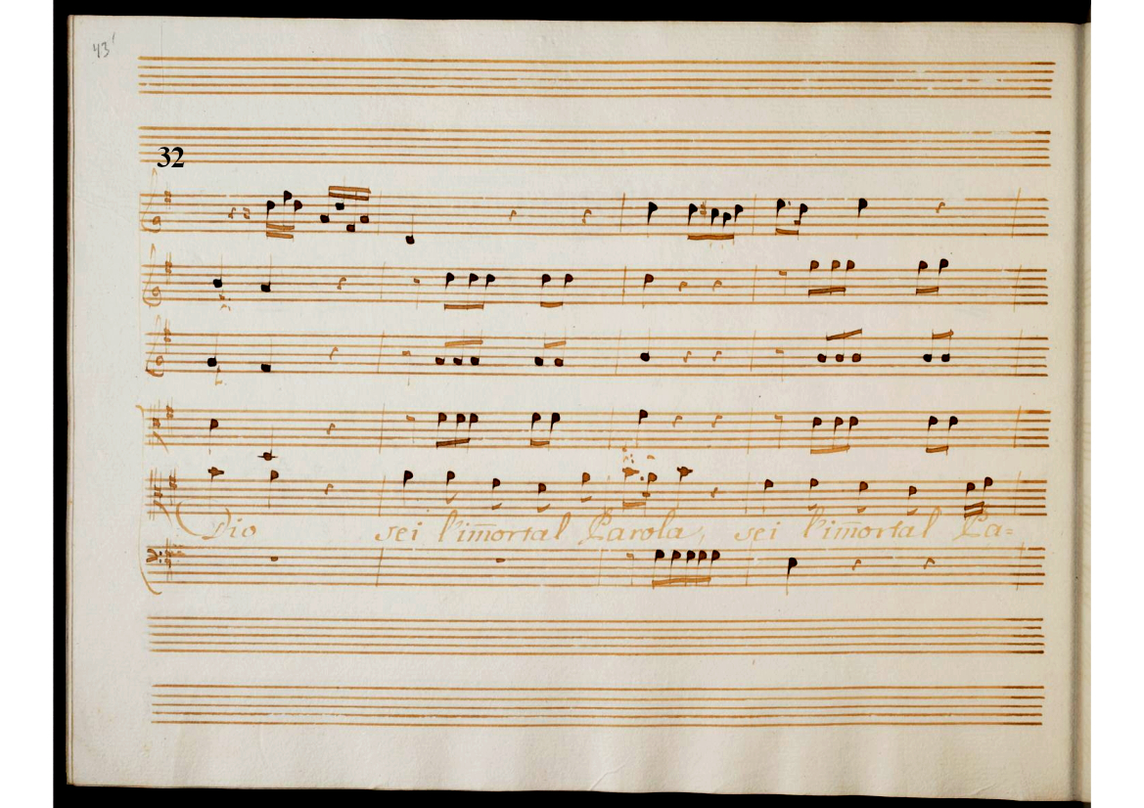

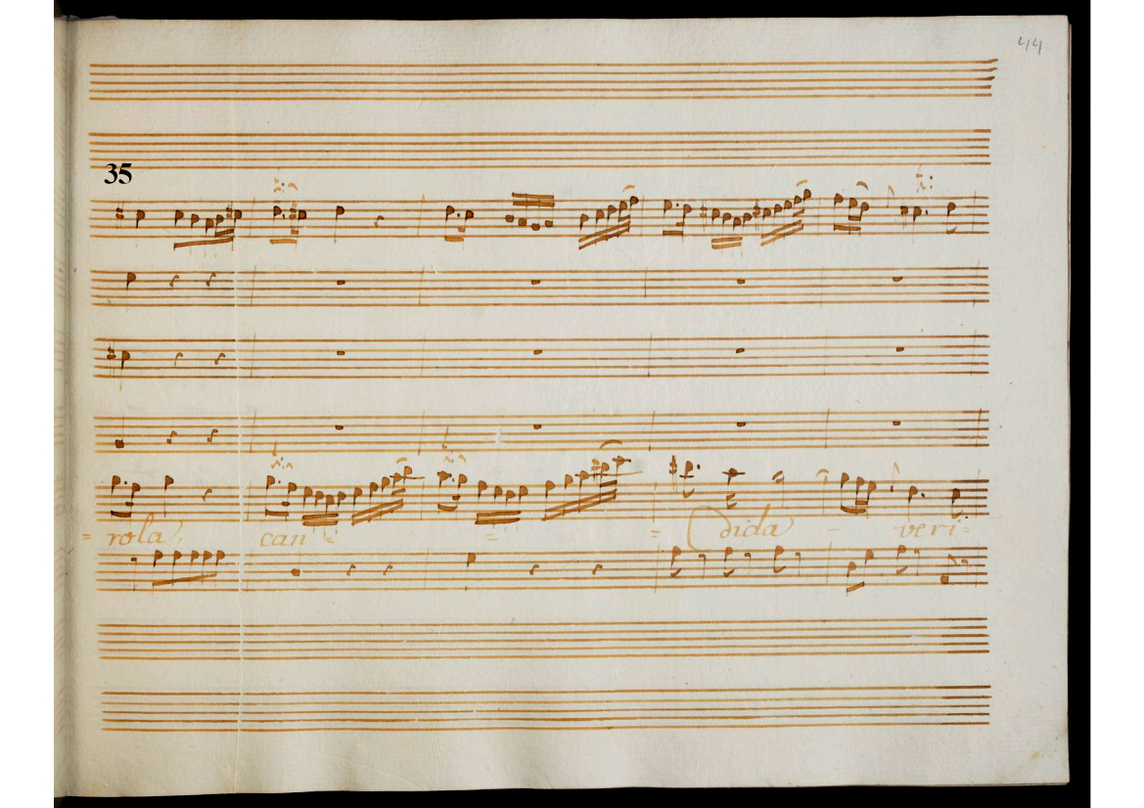

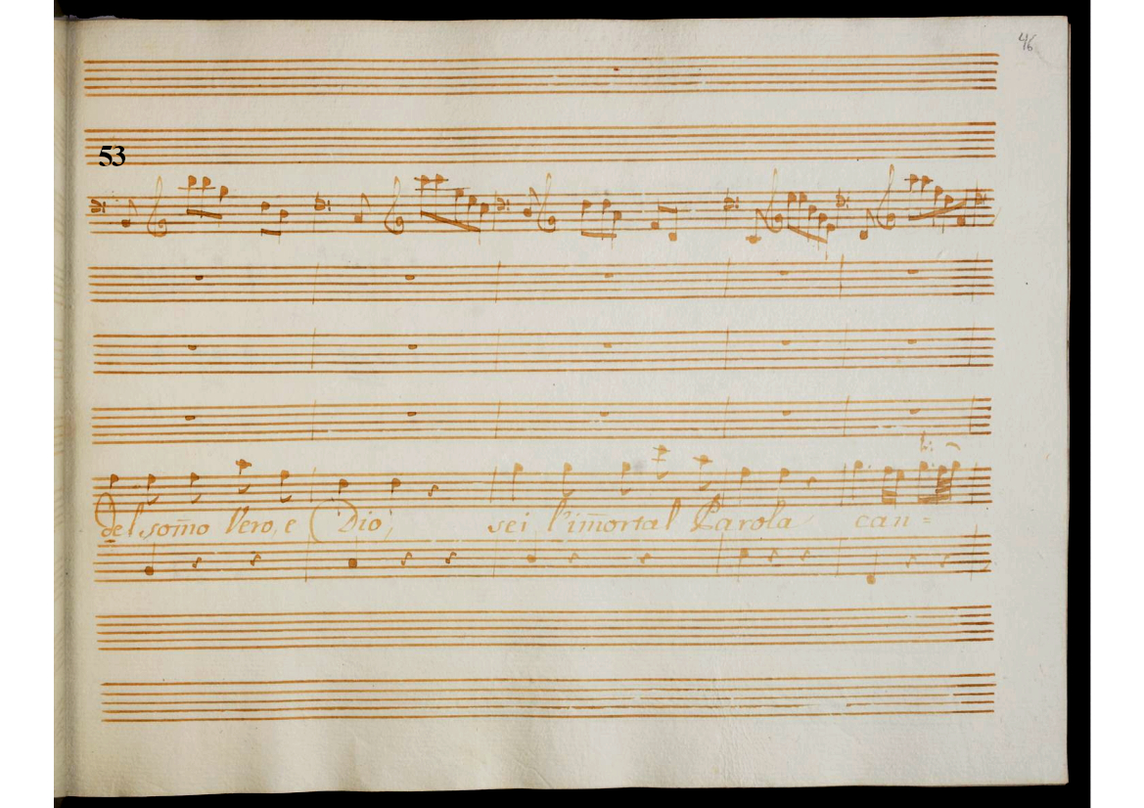

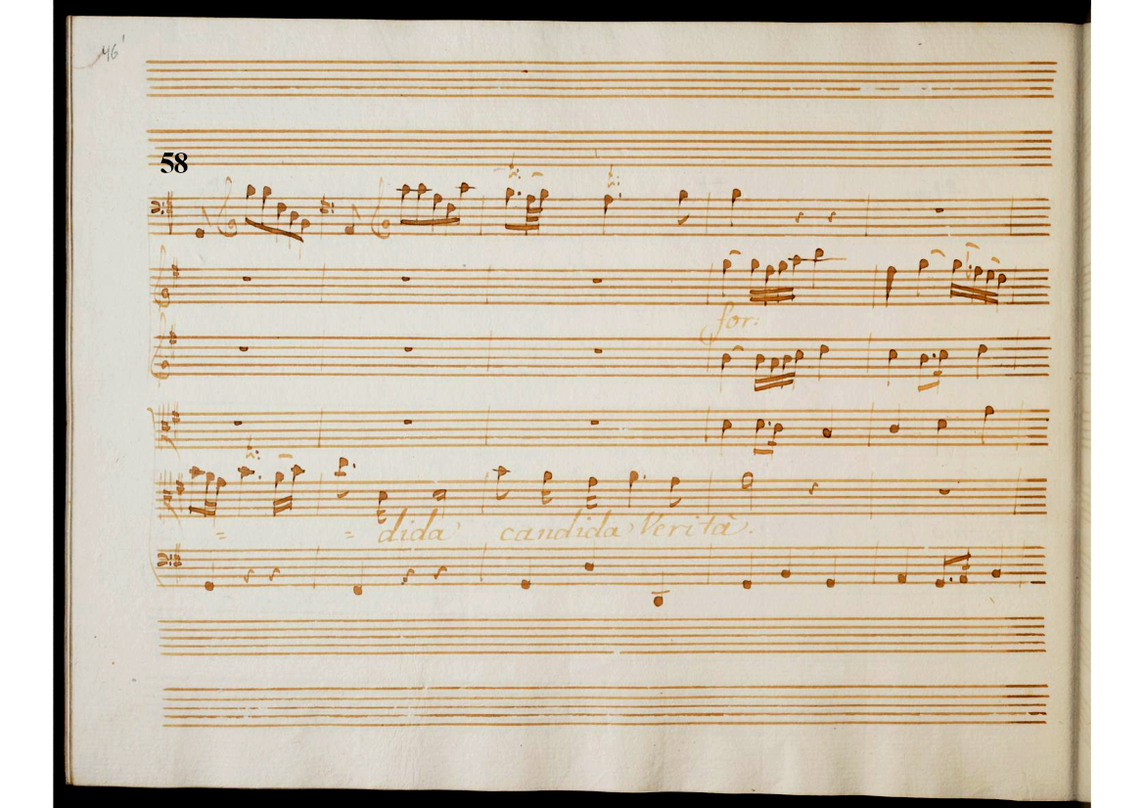

Eliacim then repeats twice "sei l'immortal Parola" (you are the immortal Word), before vocalizing on the word "candida" (candid, pure) bar 36. The salterio joins him on this vocalise where the strings have become silent. Eliacim ends the first exposition of the text by repeating "sei l'immortal Parola, candida verità".

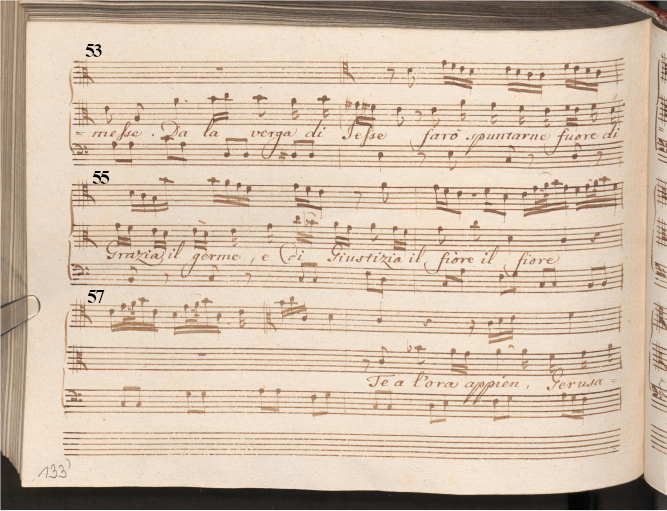

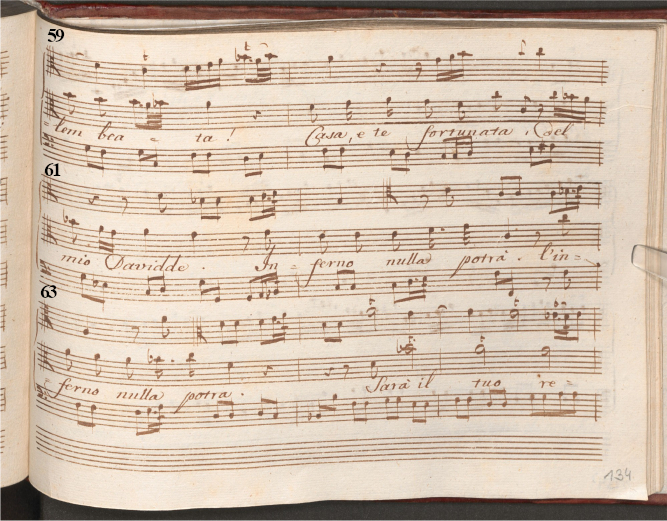

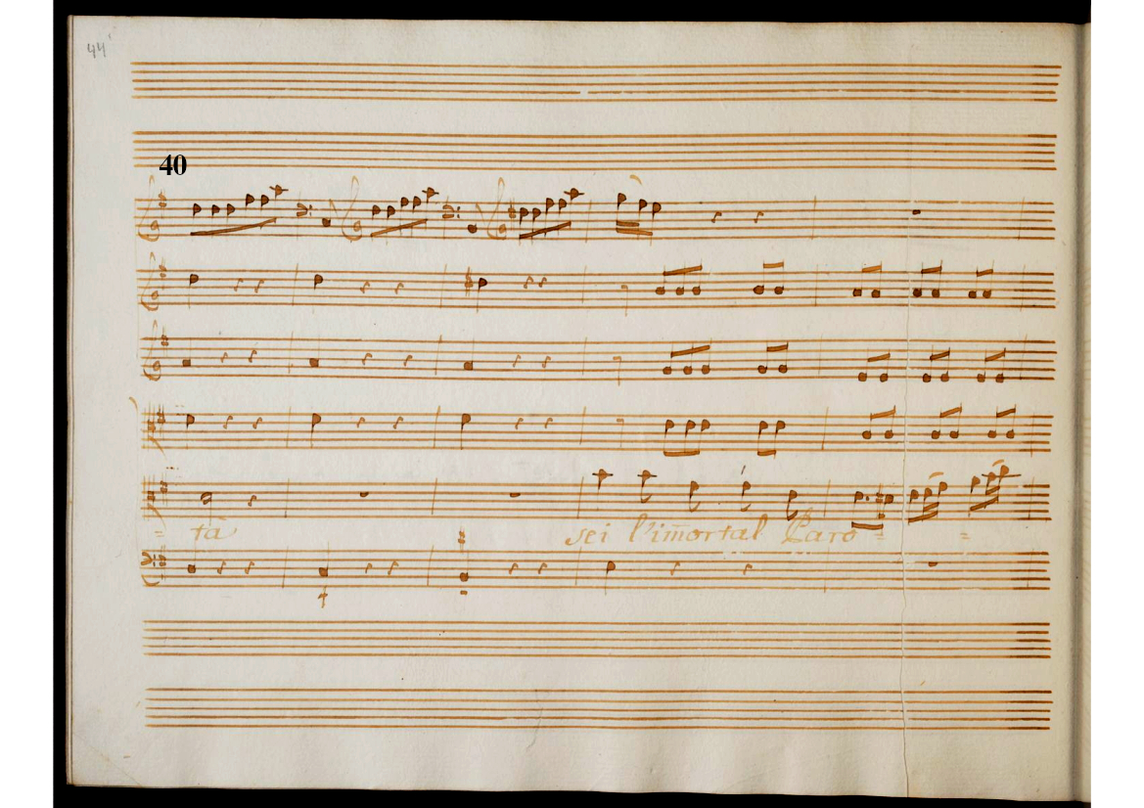

The second exposition of the text begins at bar 51 after a short harmonic march to the salterio as in the introduction. Eliacim is alone with the basso continuo and the salterio, as if the instrument were the means of making his prayer to God heard, or as if the words were translated into divine sounds by the obbligato instrument.

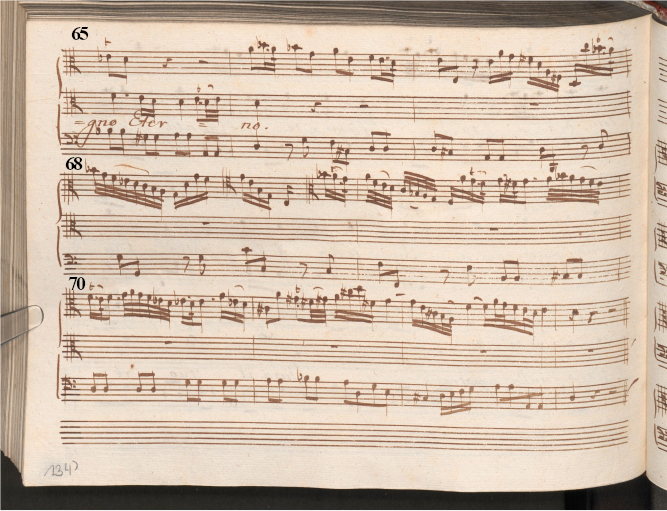

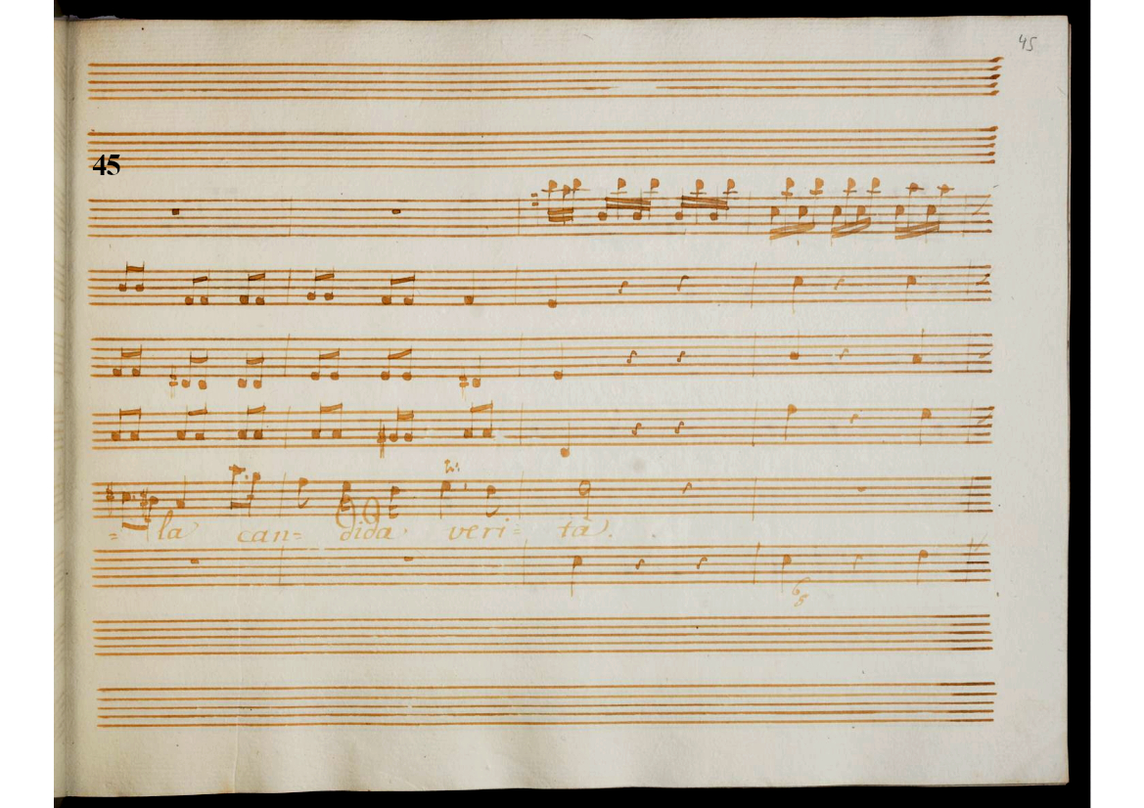

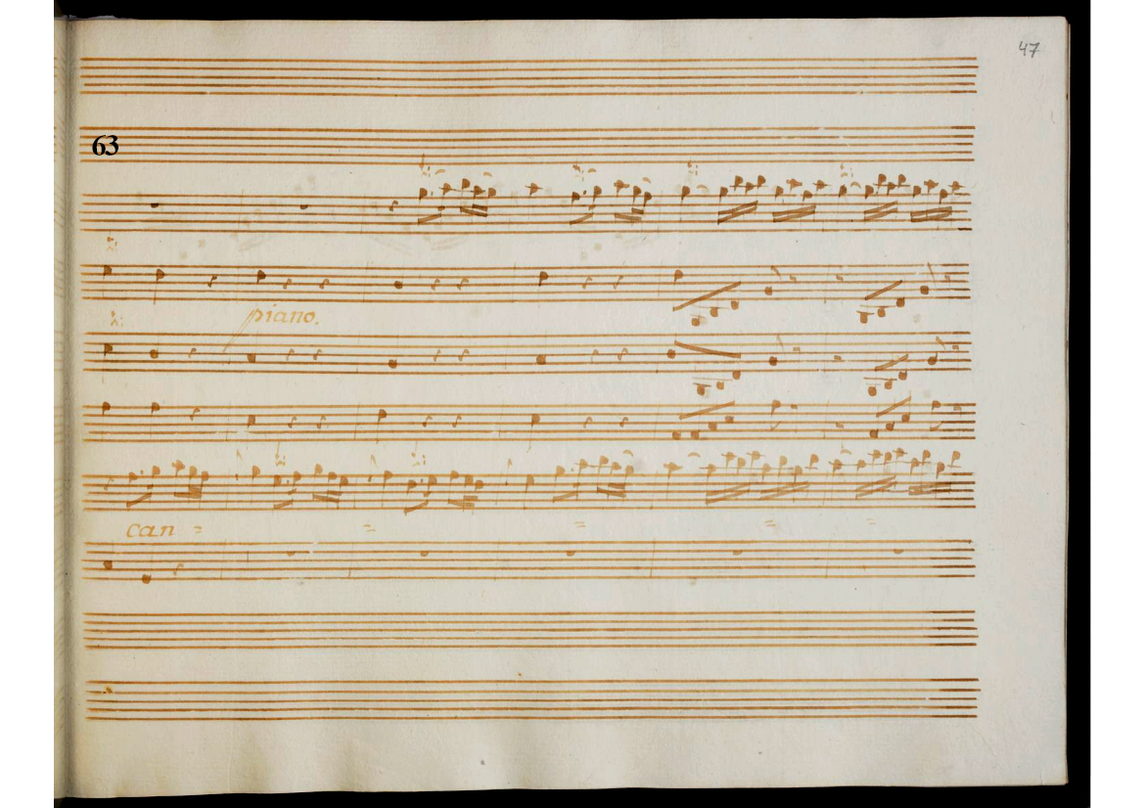

At 61, the strings enter again, taking up the melodic motif of "reggimi, o tu" from the first sung exposition. At 63, Eliacim begins a new vocalise on "candida", joined at 65 by the salterio in imitation of his melody until the final cadenza of 70.

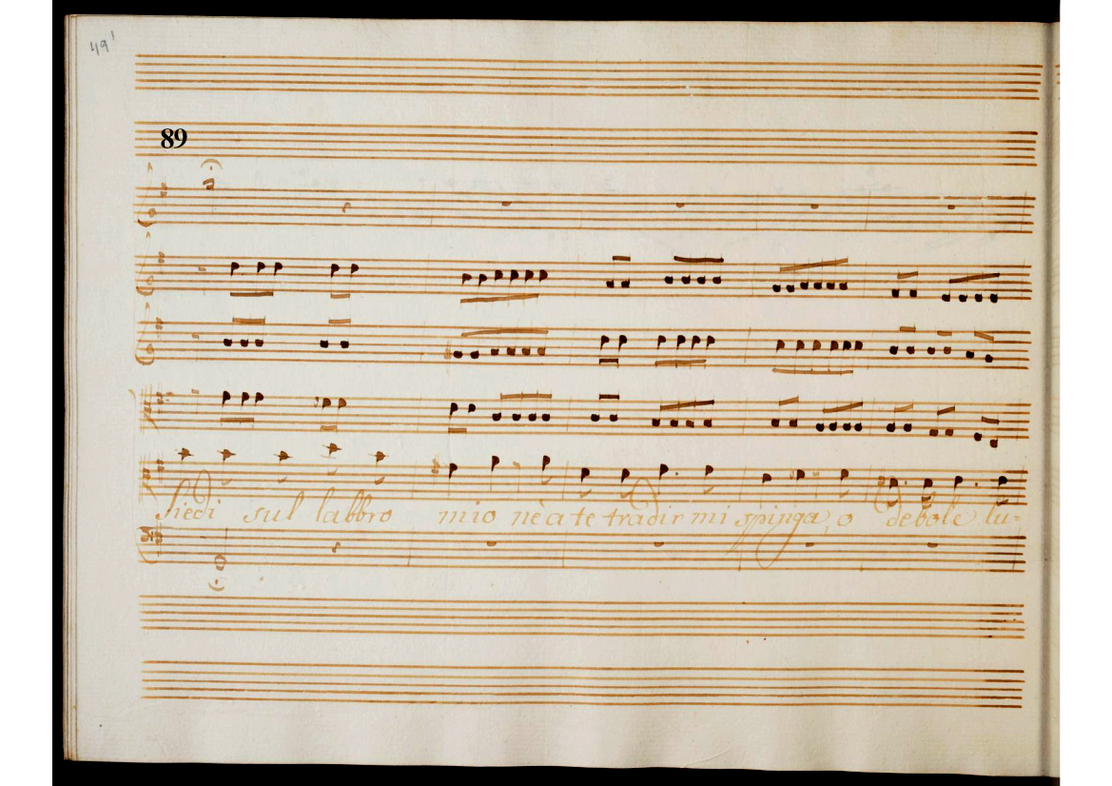

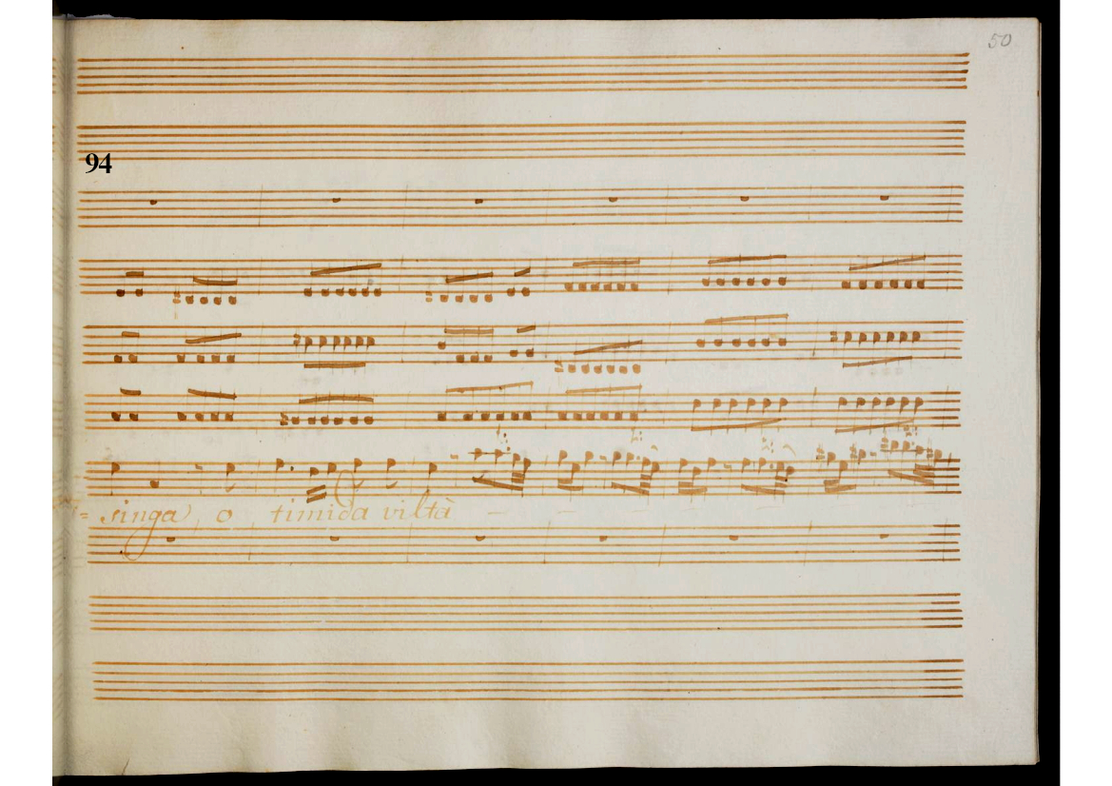

The salterio is then alone until the beginning of the B part, measure 89 in a rather free ritornello quite different from the beginning.

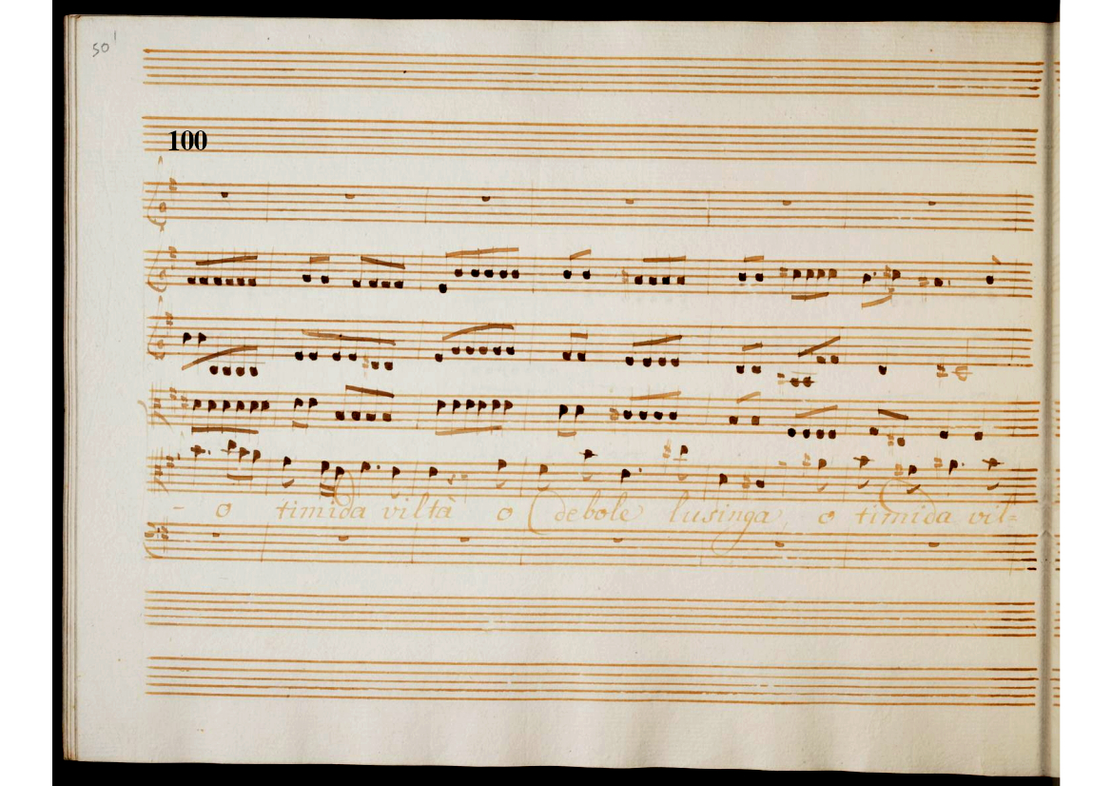

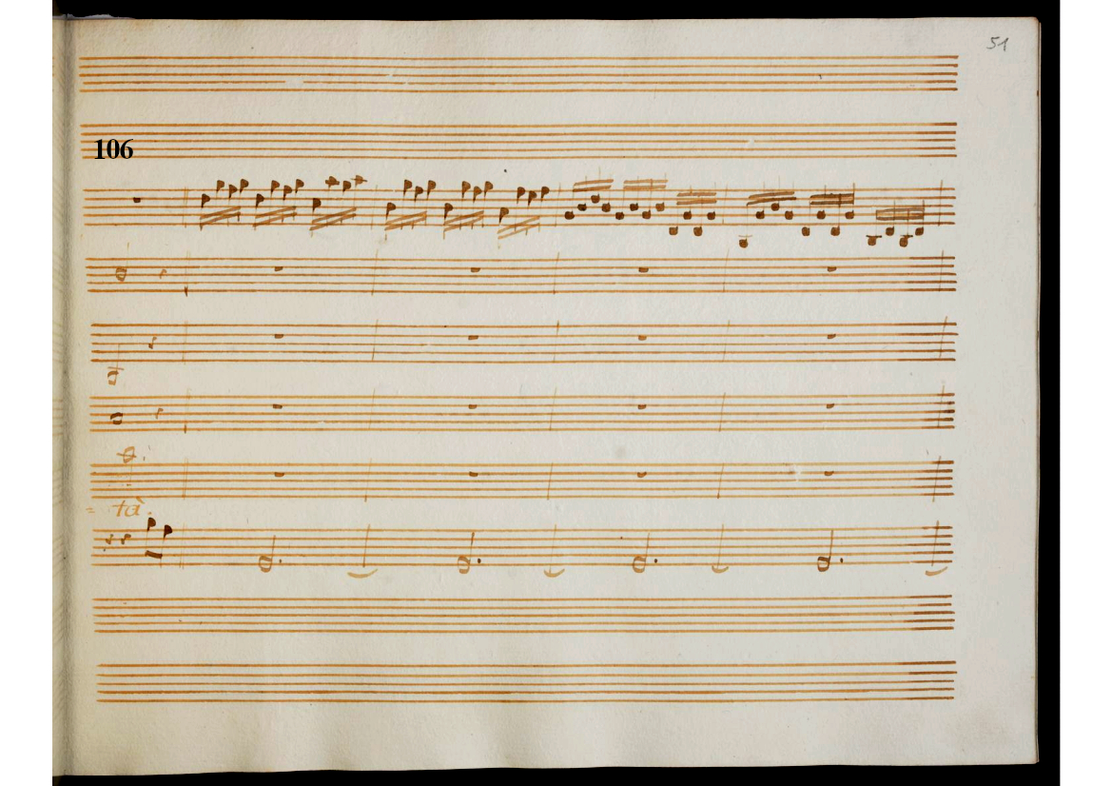

The B part is much shorter than part A with only one exposition of the text. Eliacim sings with the strings, without the salterio and without the basso continuo.

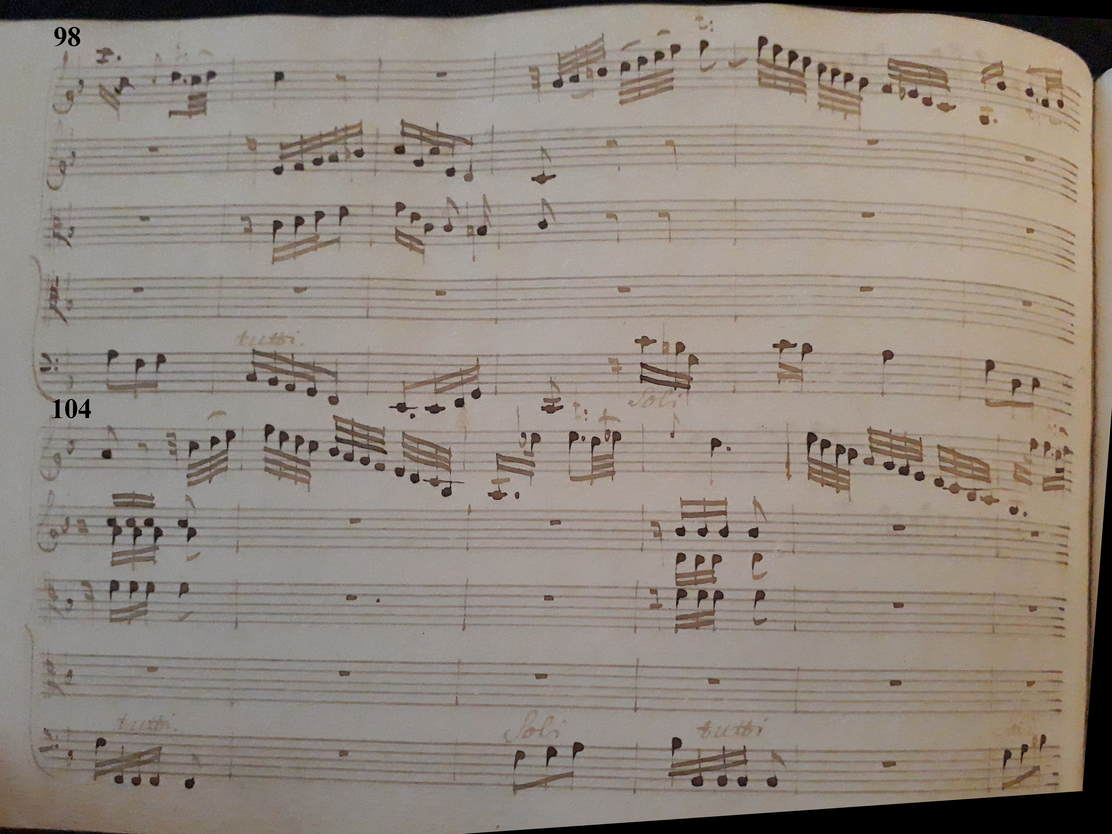

Bar 98, a short vocalise appears on the word "viltà" (cowardice). The B part ends after the repetition of "o debole lusinga, o timida viltà" (o weak flattery, o timid cowardice) at bar 108.

For me, this aria, like the other three with salterio in Caldara's oratorios, is really linked to the expression of the divine, whether through prayer or through the transmission of the divine word through the character. As if the salterio, with its light, sonorous, soft and brilliant sound, could transport our feelings and soothe them. The long introductions of each of the 4 pieces with salterio are for me like a time given to the listener to taste this new atmosphere, peaceful and deep.

Here, the instrument is made like the voice of God, or as a means of transforming the words into divine sounds that will make it reach God. Sometimes taking up the melody sung in imitation and on the vocalisations of certain important words, I have the sensation that Elicaim's words will be heard and that he will be supported, as if enveloped in this soft and luminous halo of sound.

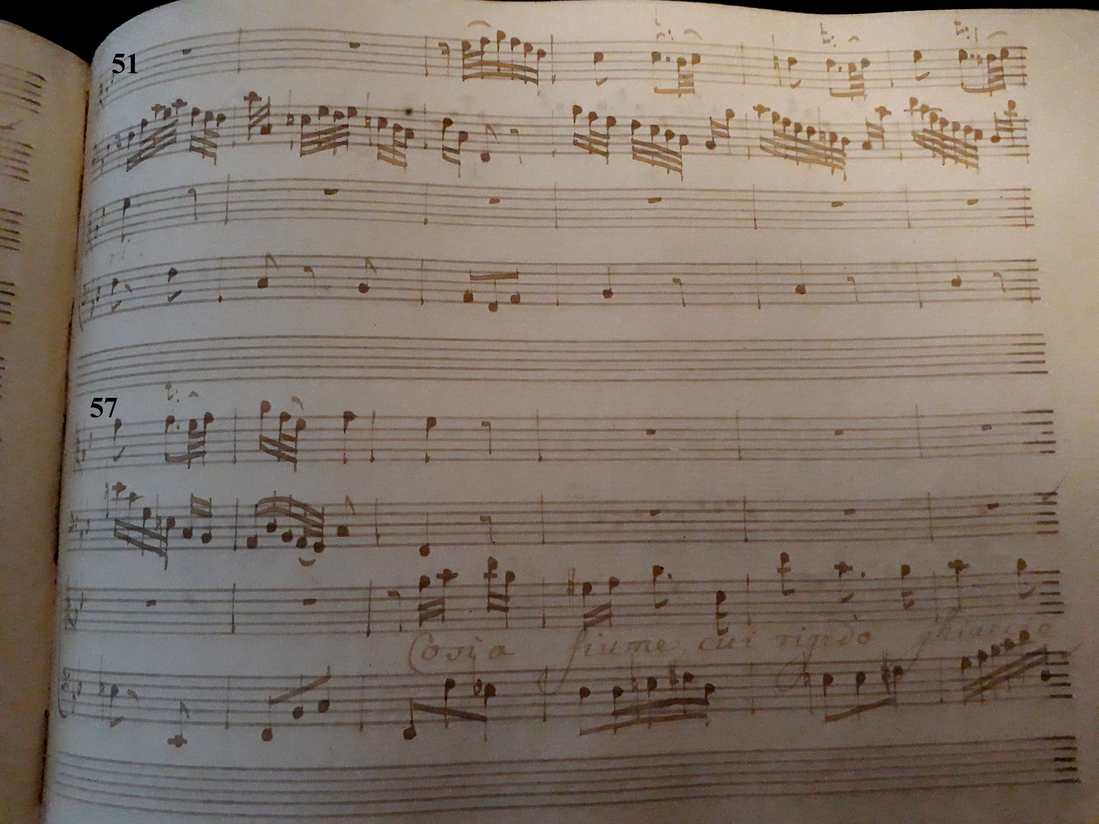

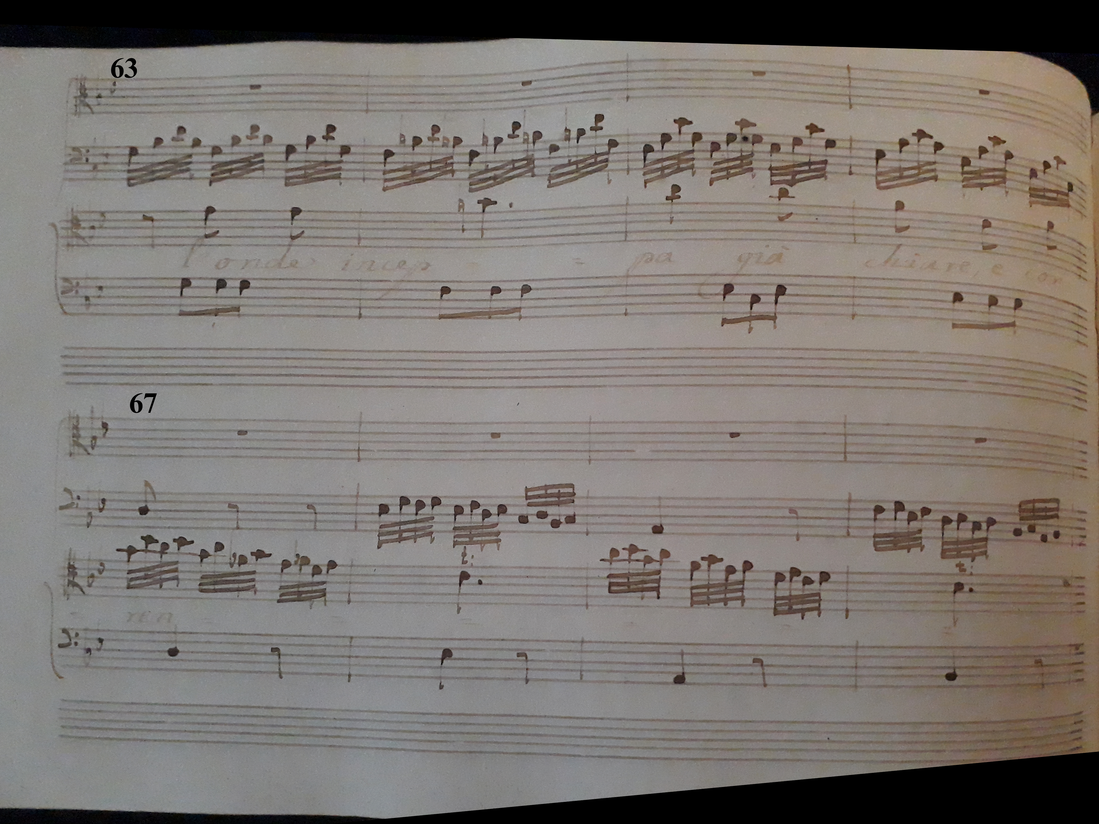

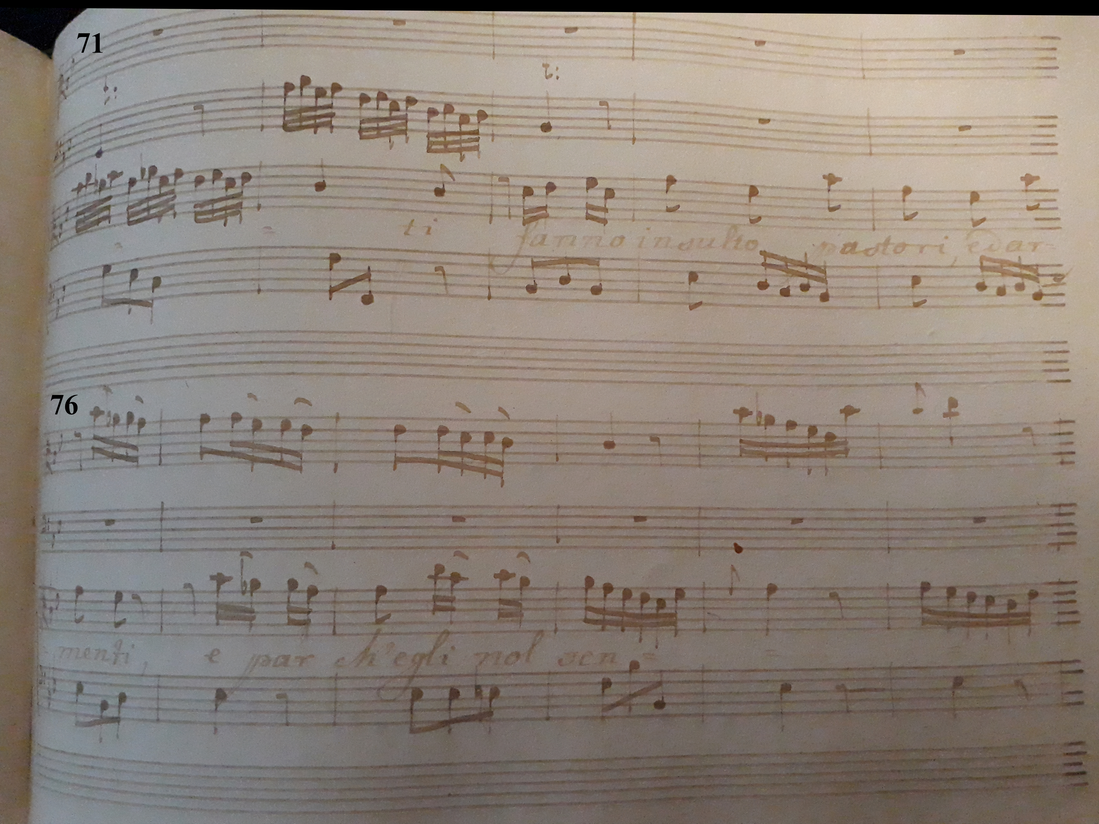

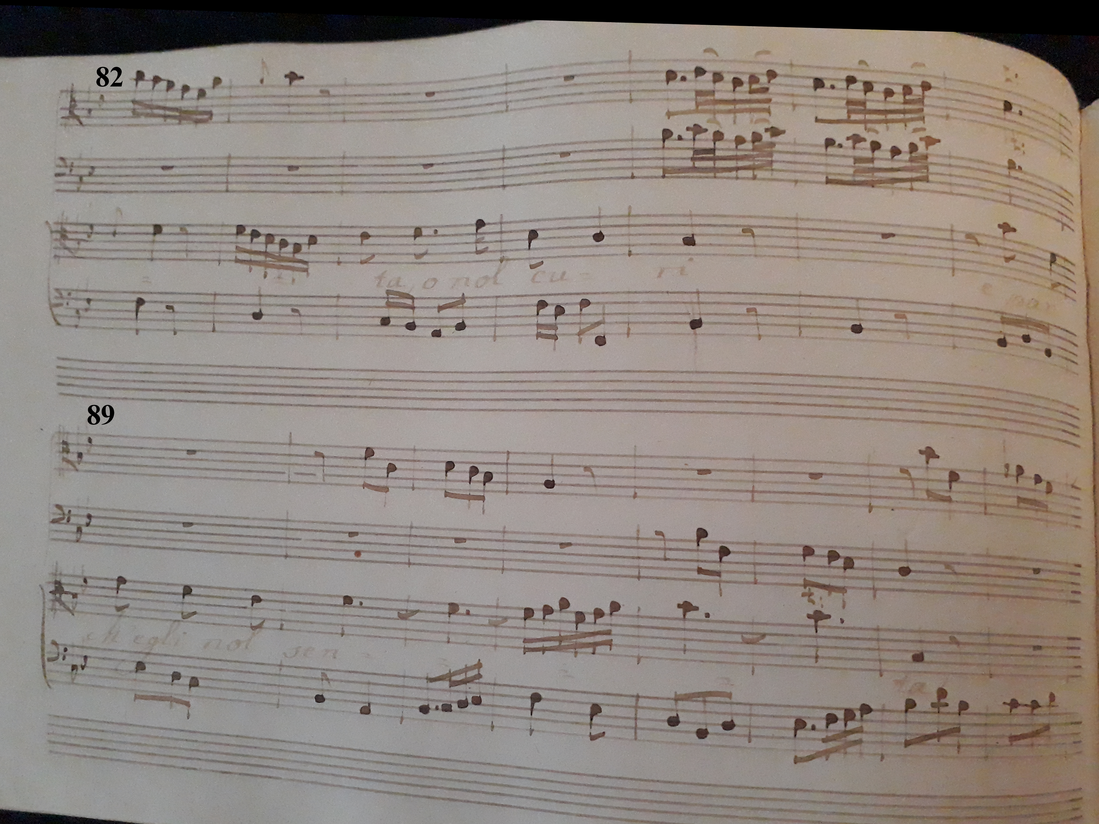

"Cosi a fiume cui rigido ghiacco", Jojada, in Gioaz Rè di Giuda (1726)

Alex Potter - countertenor, Catherine Motuz - tenor trombone, Carles Cristobal - bassoon, Ensemble La Fontaine. Record in October 2012 for Outhere Music

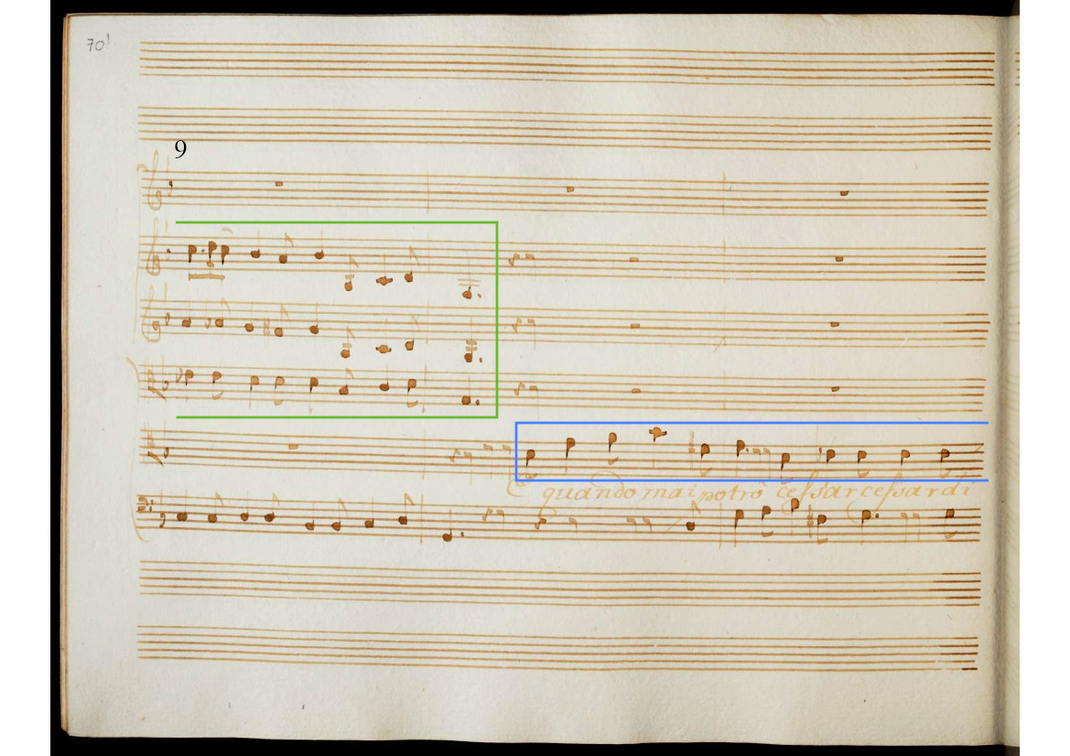

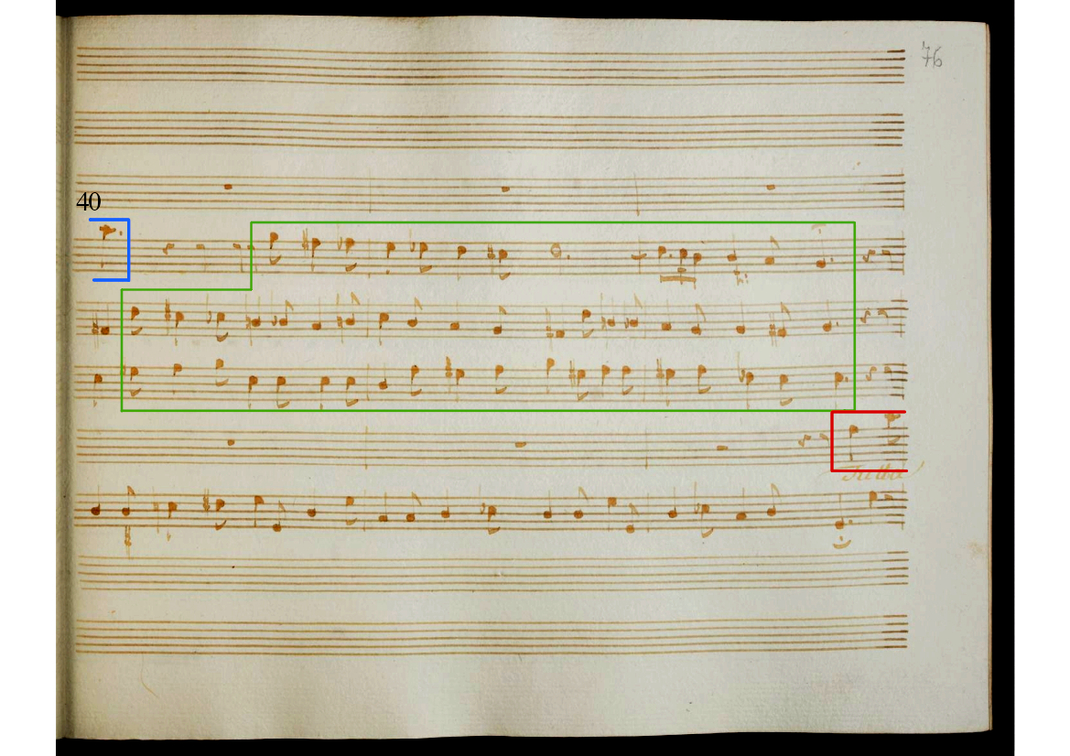

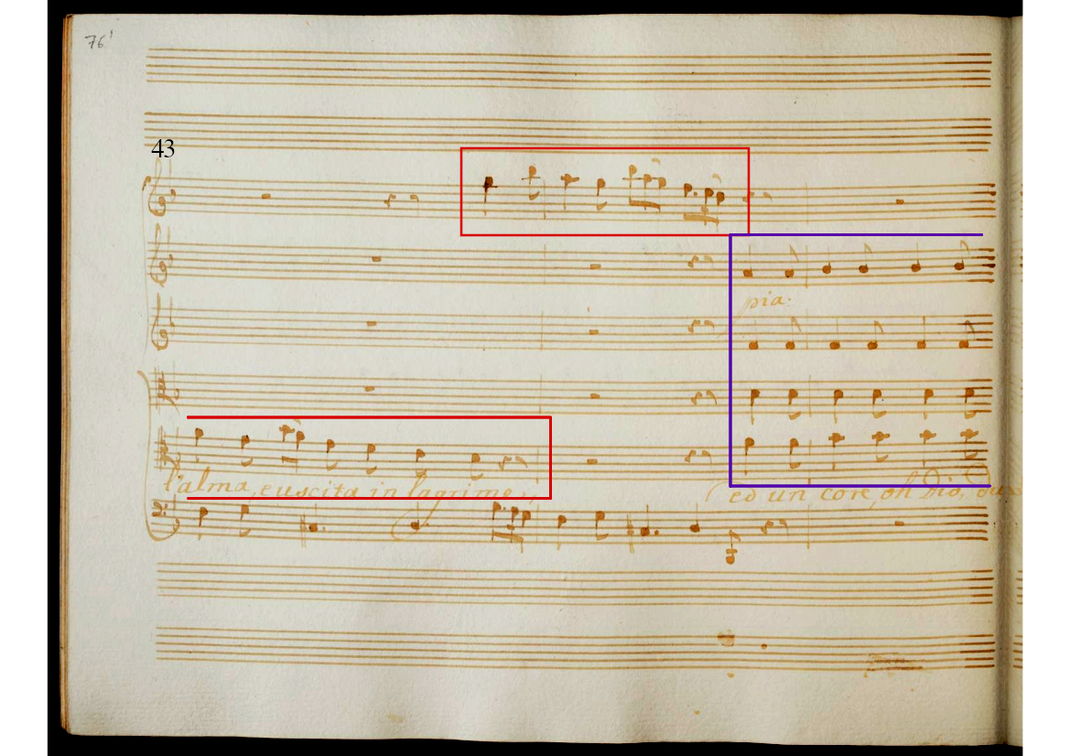

Suffering aria - analysed example: Gioseffo

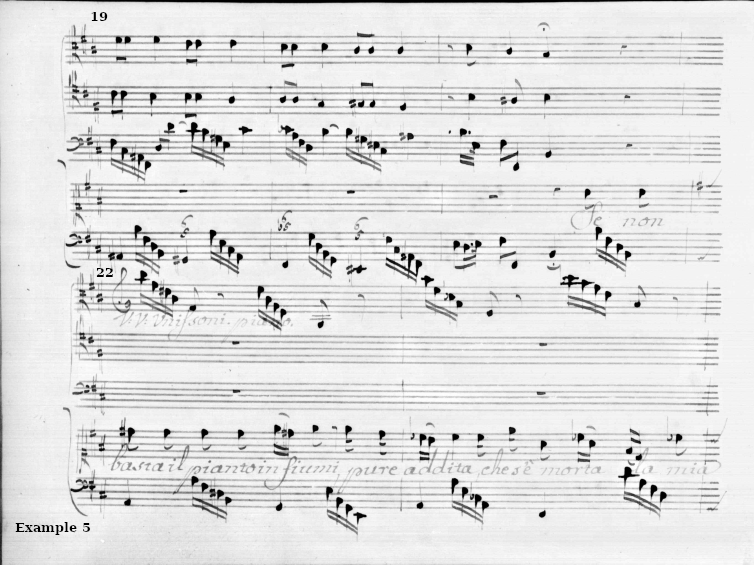

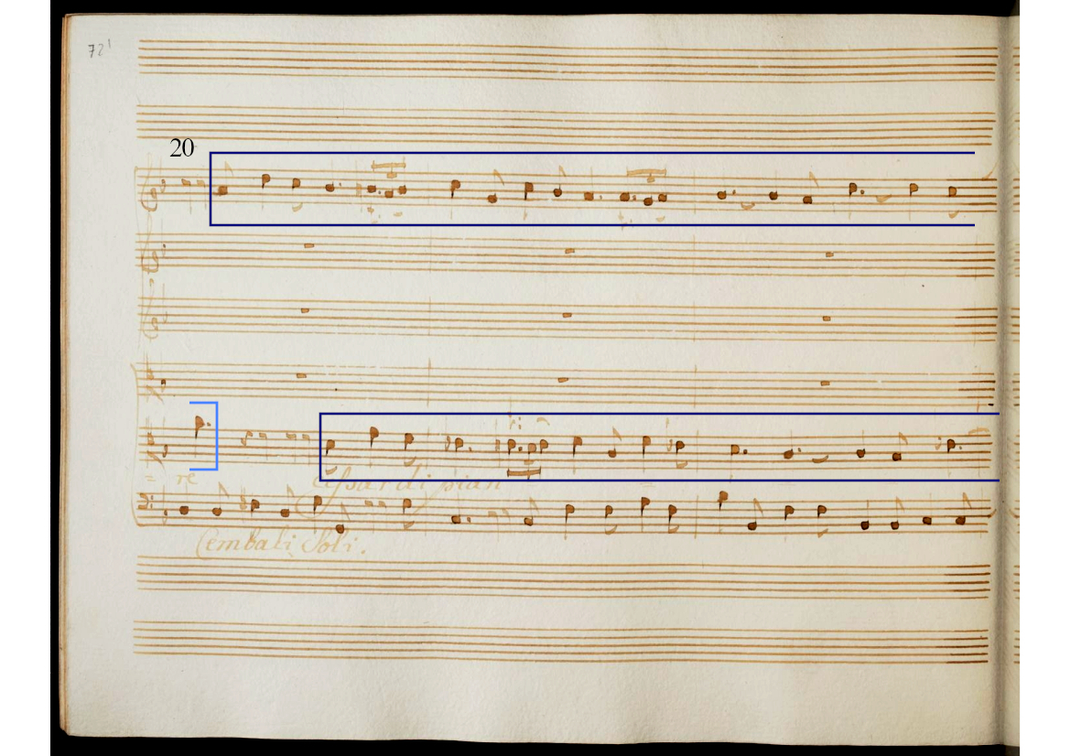

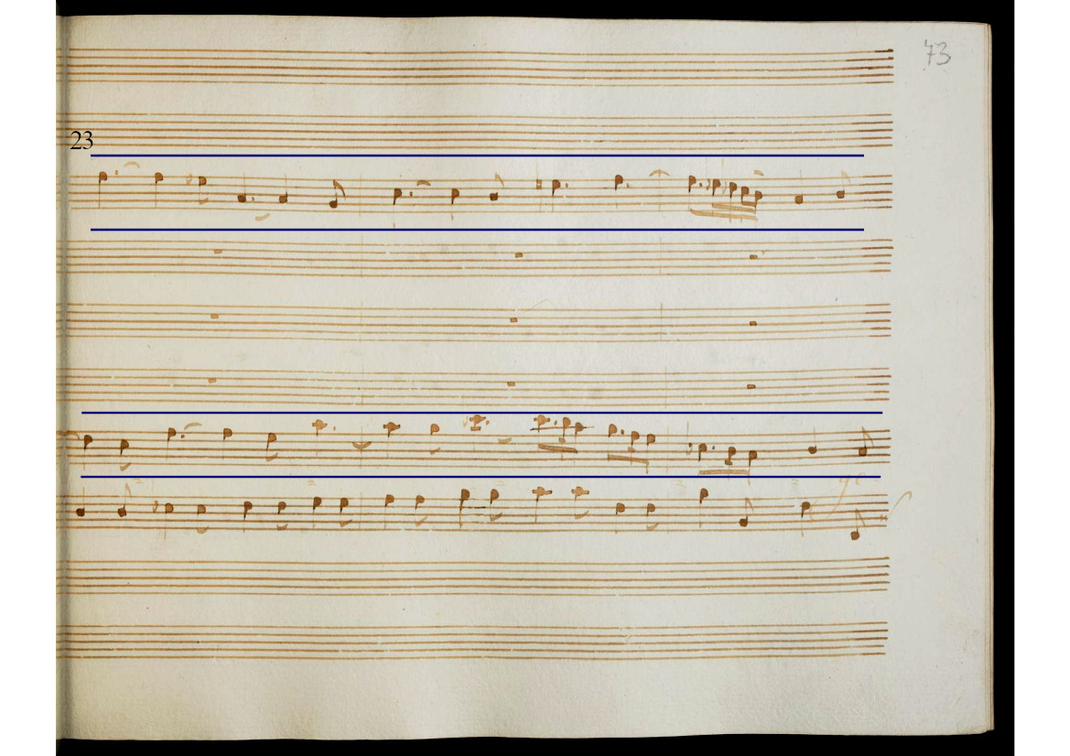

In the oratorio Gioseffo chi interpreta i sogni, this aria is the second sung by Gioseffo. It comes at a moment when Gioseffo has just interpreted two dreams that have turned out to be true, but he is still imprisoned in the pharaoh's prison with little hope of ever getting out. Outside, he hears the noises of the feast given by the Pharaoh, and laments himself.

In part A, he wonders if he will ever stop crying, and tells us in the B part that his soul has burst into tears, and that his heart is so hard that nothing can touch him anymore.

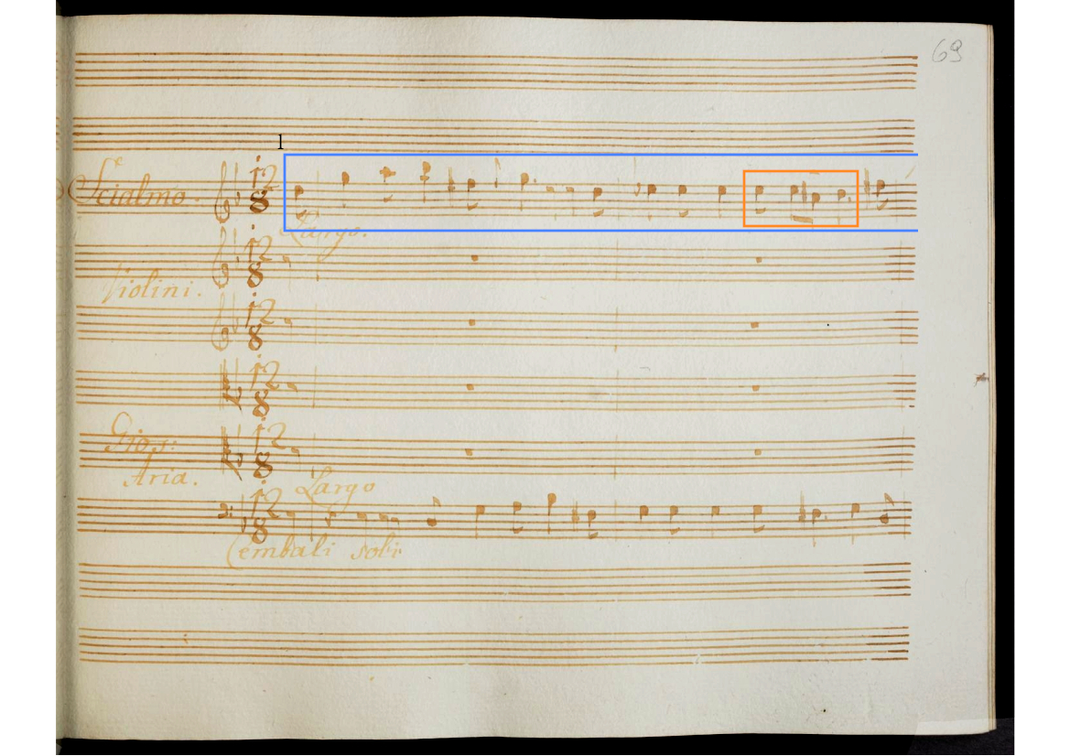

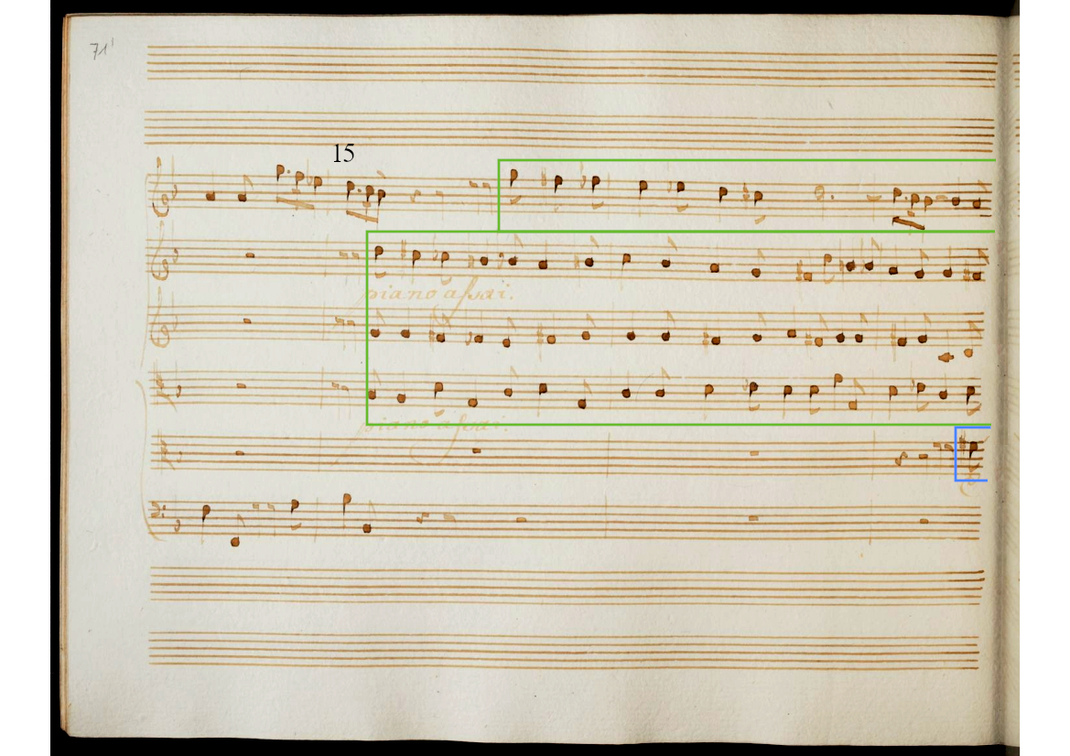

The aria is slow, largo, with this slight pendulum feeling due to the 12/8. The two tonalities of G Minor and C Minor are particularly appropriate for this soft and poignant lament, which makes us hear his tears flowing endlessly in long chromatic streams descending with the chalumeau and the strings. In this aria we can find the typical melodic phrases of Caldara with those diminished intervals that accentuate the lament.

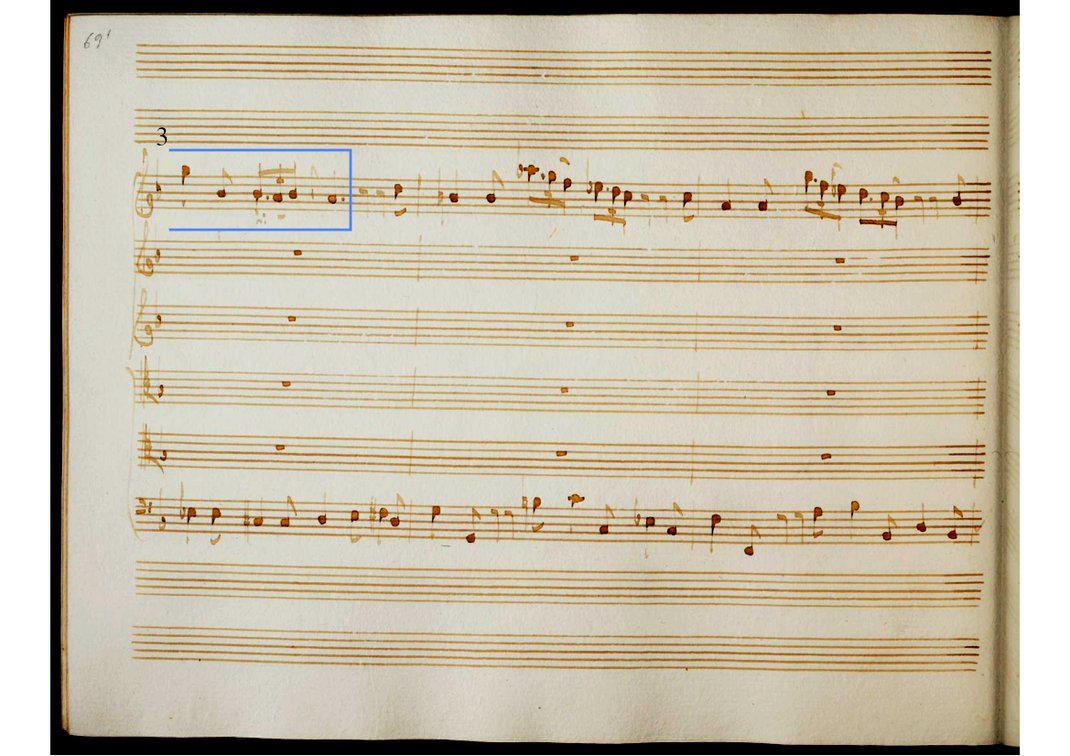

The chalumeau introduces the aria with the melody which will then be sung by Gioseffo. Before the entry of the voice, and when the chalumeau has finished the introductory ritornello, the strings join for a transition of about two bars on this descending chromatic motif which will then be found in the chalumeau.

On the first exposition of the text, the voice is only accompanied by the basso continuo, to allow, in my opinion, a perfect audibility of the text, with no other timbre than that of Gioseffo. Before the second entry of the text, we find the chromatic motif of tears on all instruments (except the basso continuo), in a plaintive, weeping choir. The second exposition of the text is again “naked”, as if to insist on Gioseffo's pain.

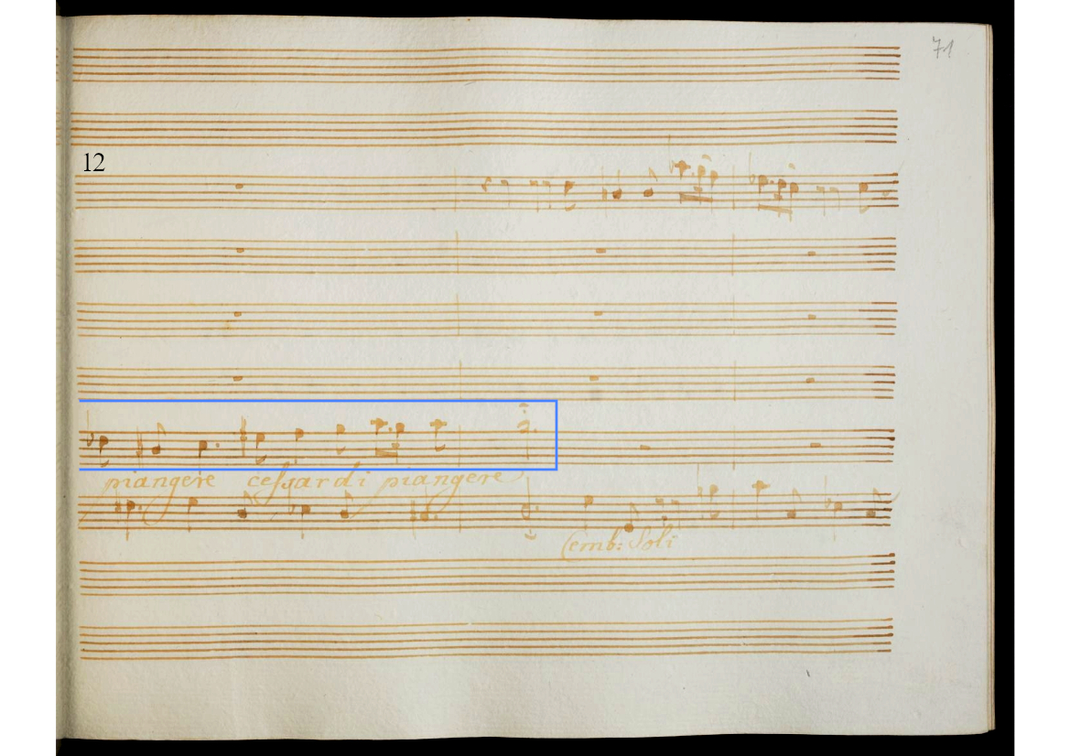

He then repeats "cessar di piangere" (stop crying), and is joined by the chalumeau on the long, plaintive vocalise that follows on the word "piangere" (cry).

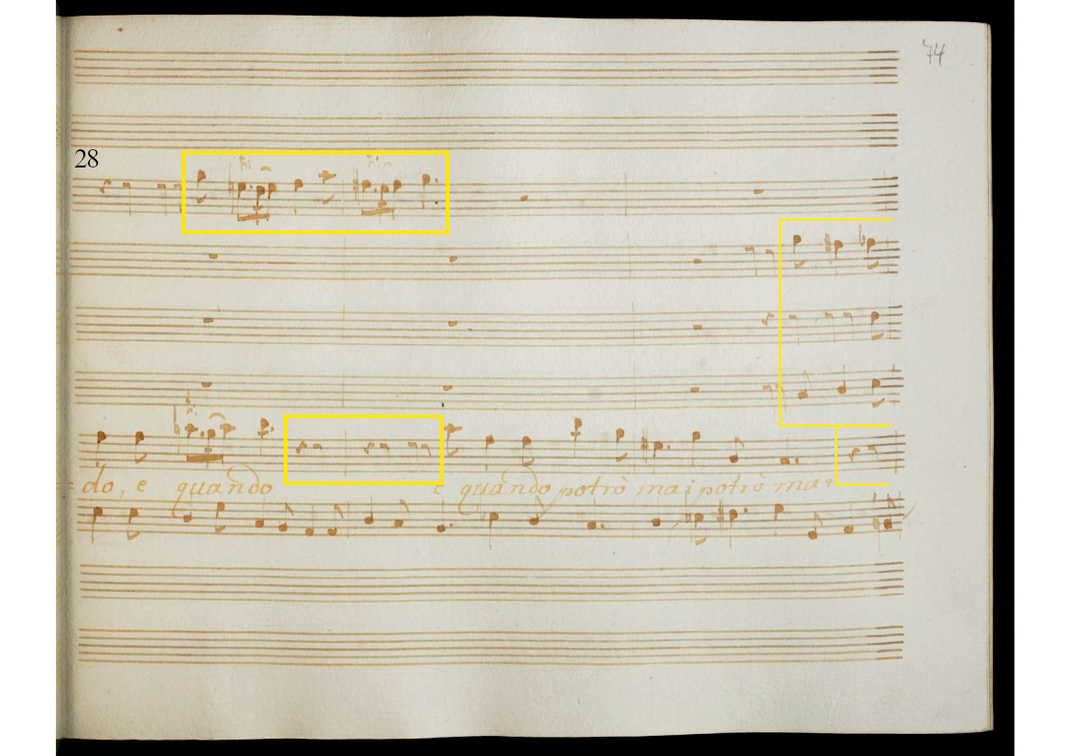

Before the third and last exposition of the text, which moreover becomes longer and longer and is interspersed with silences (sighs of Gioseffo?), we find the chromatic motif in the strings.

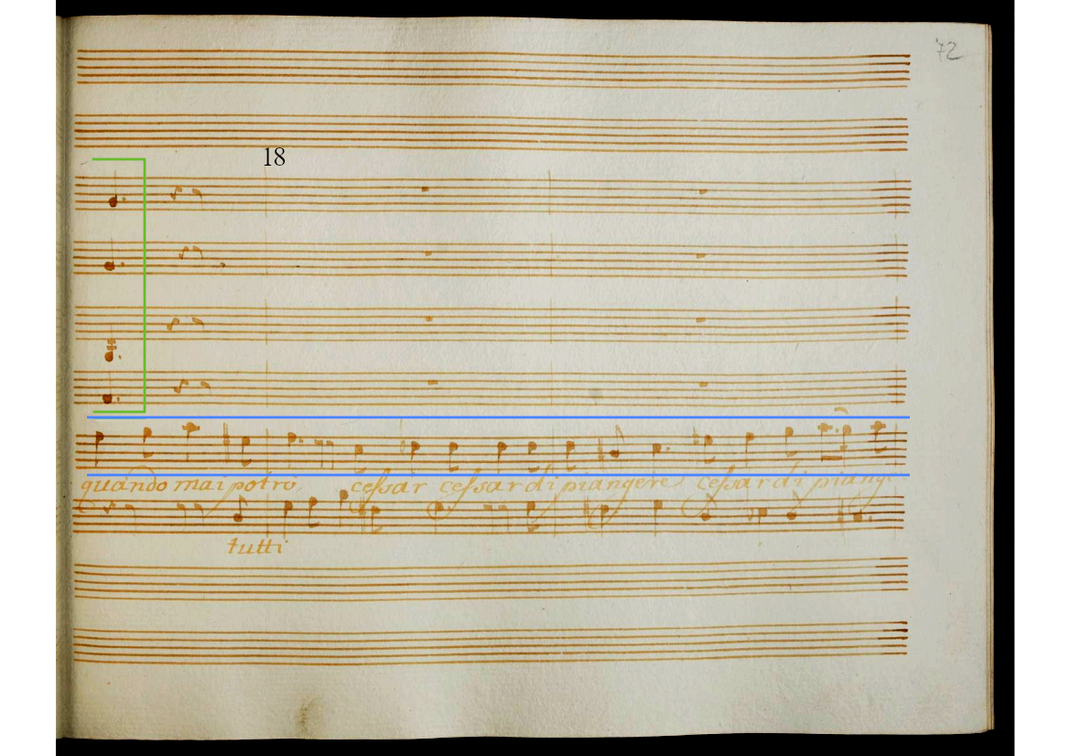

This last exposition of the text therefore becomes more plaintive, long and slow as Gioseffo repeats the words: "è [sic] quando, è quando (pause with echoes of the chalumeau), è quando potrò mai, potrò mai (pause with a measure of the chromatic motif on the strings) cessar di pia_______ngere (with chalumeau on the vocalise)". The concluding ritornello of the aria is then done only with the strings, which take up the first three bars of the melody before continuing for a last chromatic lament descending to the final cadenza.

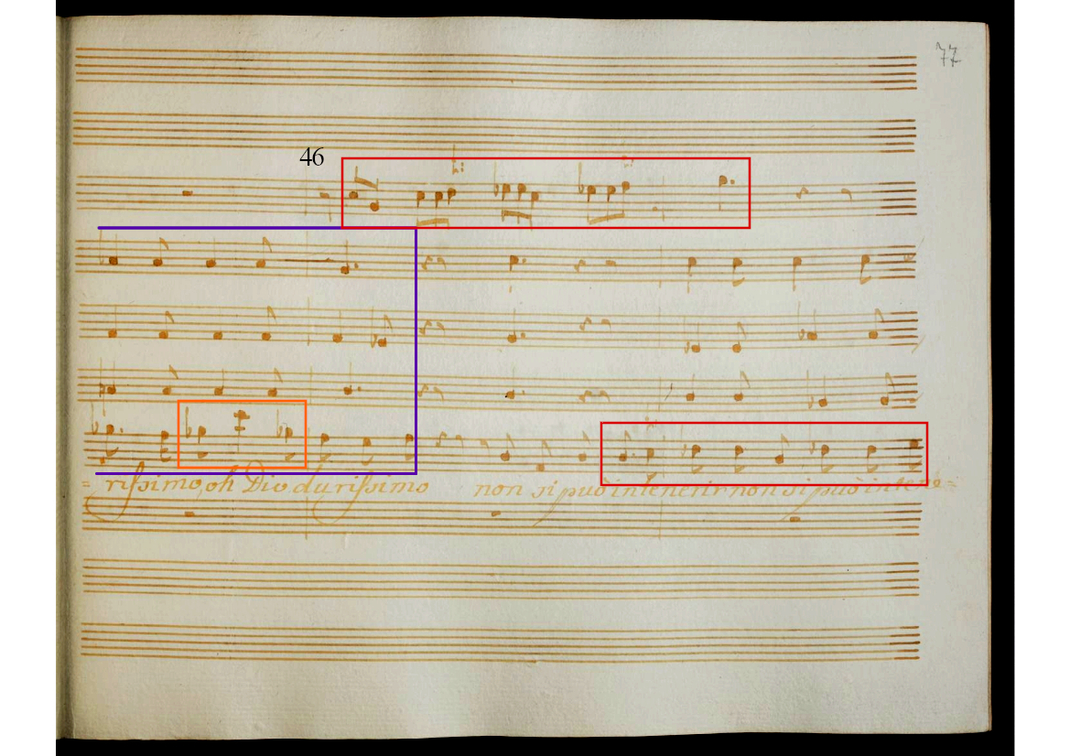

The B part is particularly brief in comparison with part A, as Gioseffo exposes the text only once.

He begins alone with a one-bar phrase, which is then repeated with a chalumeau. It is then carried by a string choir for the next phrase repeated twice in a row "ed un cor, oh Dio, durissimo", with during the repetition an accentuation on the word "Dio" (God) with the fourth augmented (A flat - D).

The chalumeau then introduces the next phrase, taken up as it is by Gioseffo. They are found together at the beginning of the vocalization of the word "frangere" (to break) which Gioseffo ends alone with a melodic line which also seems to be broken due to the wide intervals used (fifth, fourth, sixth, seventh).

In this aria, the chalumeau is, in my opinion, used as an amplifier of the emotions already present in Gioseffo's text. Sharing similar melodic motifs and sometimes echoing them, it highlights the pain of the character. Joining the voice over important words such as "piangere" and "frangere", he joins Gioseffo in these plaintive vocalisations.

On the vocalise of the central part, after this beautiful duet with the chalumeau, Gioseffo is finally alone again, left to himself with this torn and burst vocalise reflecting his soul. His heart can't break, can't soften, even the sound of the chalumeau can't soften him and leaves him before the end of the word.

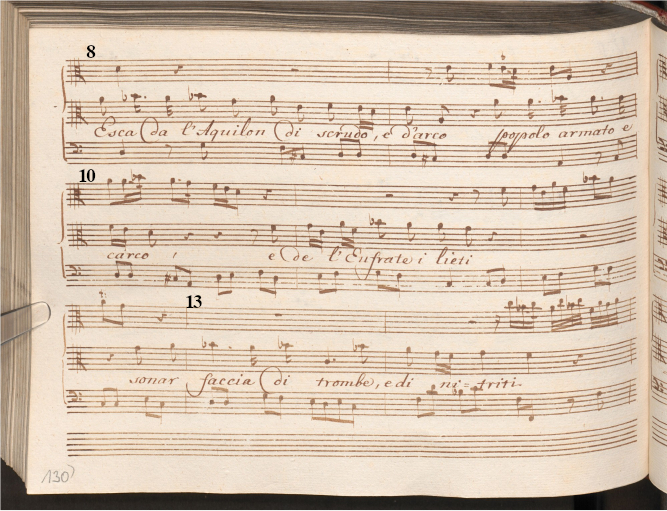

"Esca da l'Aquilon", Geremia, in Sedecia (1732)

Ulricke Becker - Viola da Gamba obligato, Valer Sabadus - countertenor, Michael Dücker - ensemble director Nuovo Aspetto, recording SONY CLASSICAL 2015

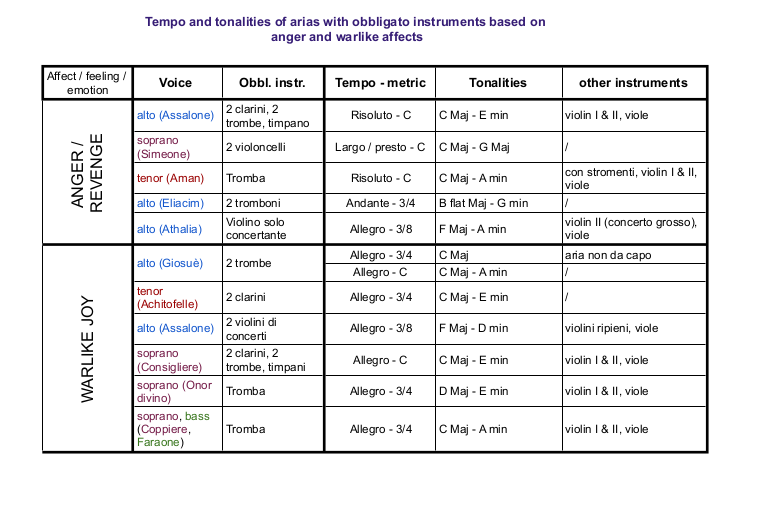

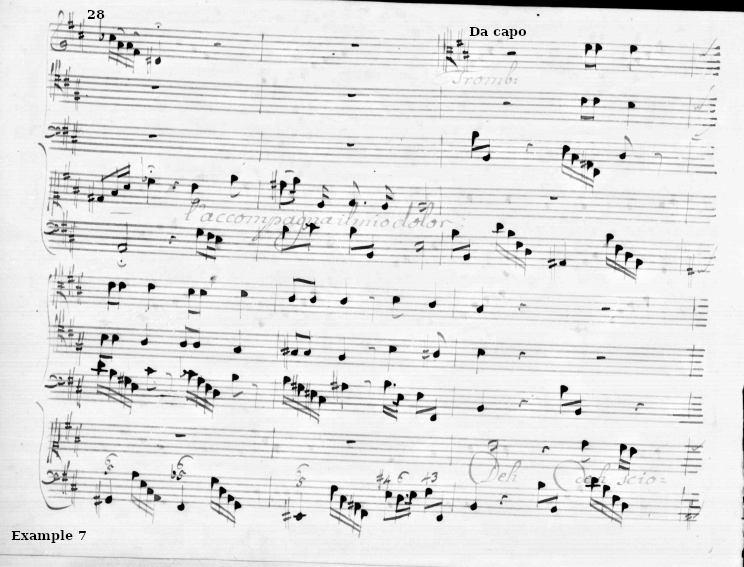

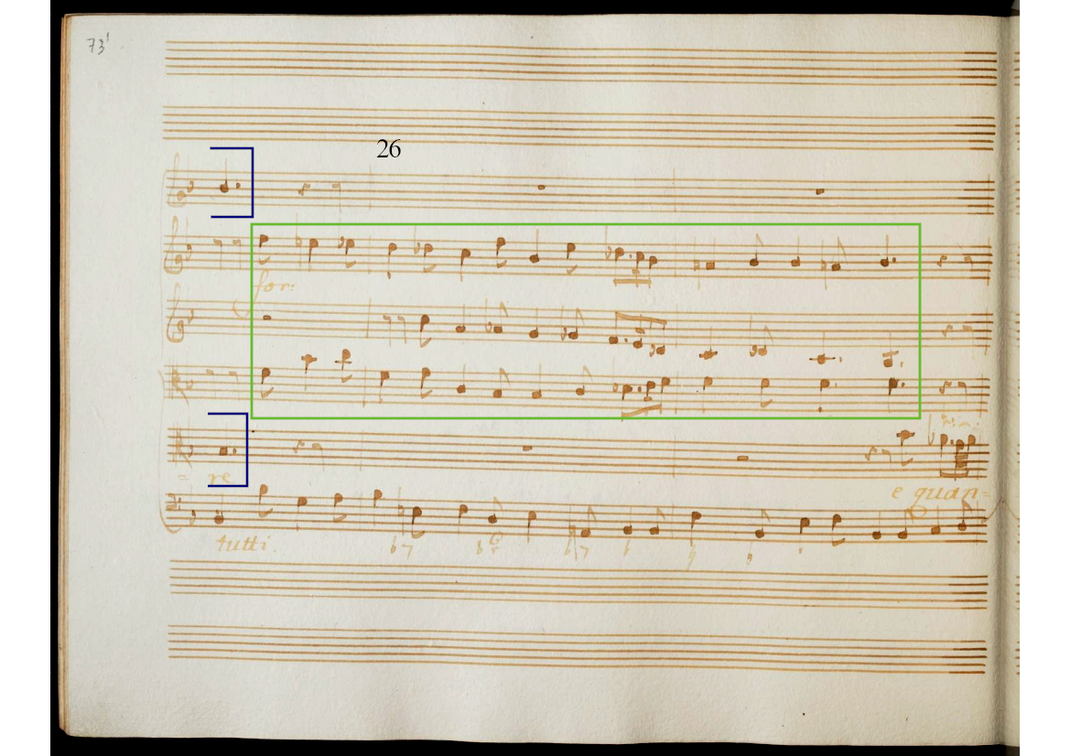

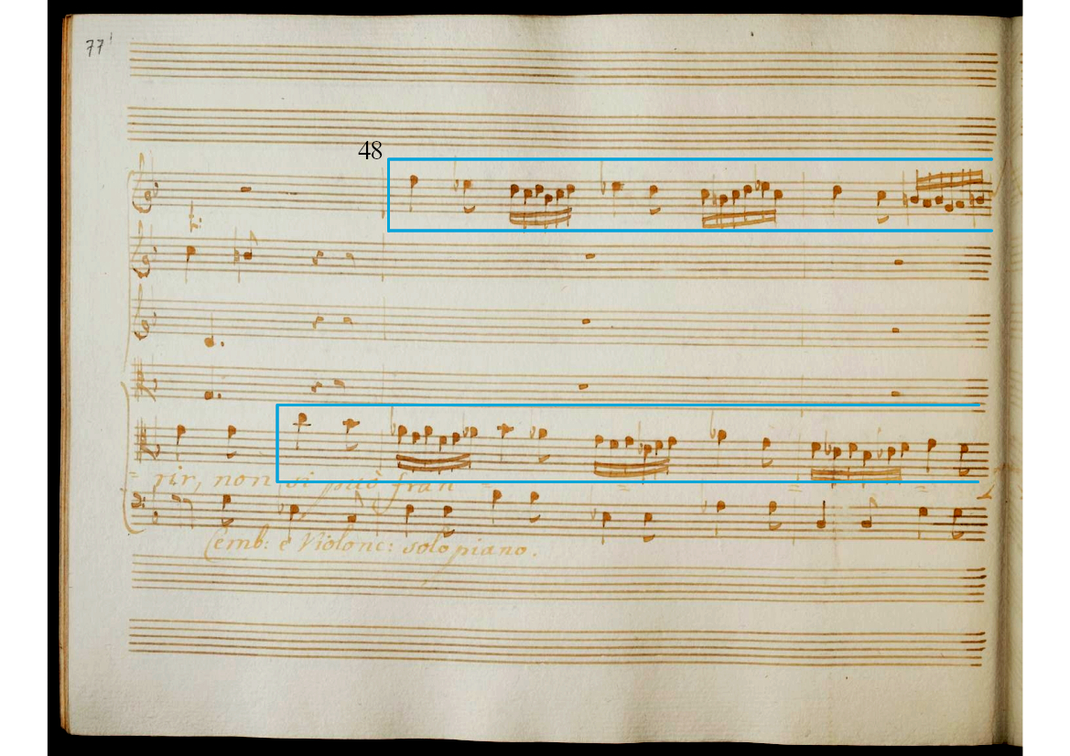

Anger, revenge - analysed aria: Athalia

This aria by Athalia is the last one she sings in the entire oratorio. In it she expresses her anger but also her fear of soon being judged for the awful crimes she committed to become queen. As her grandson, the only legitimate pretender to the throne, is acclaimed by the crowd, she vehemently sings of the future king's fury and his fear of incurring his wrath.

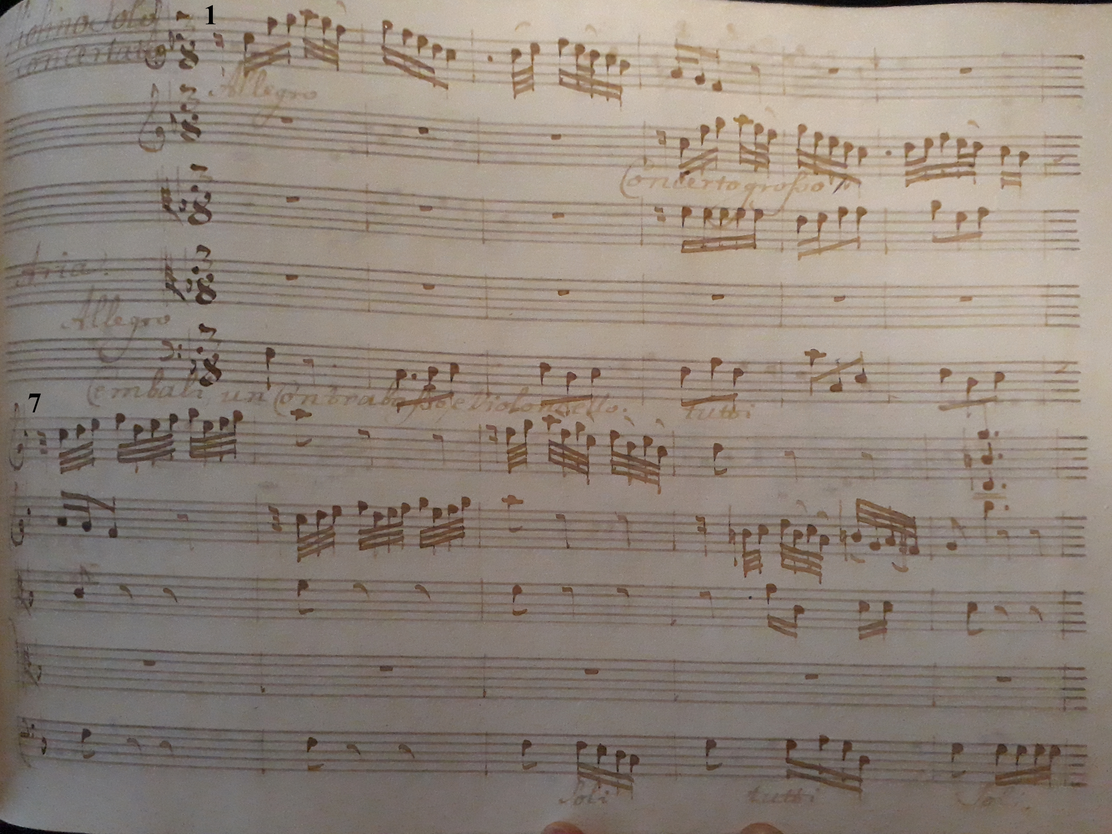

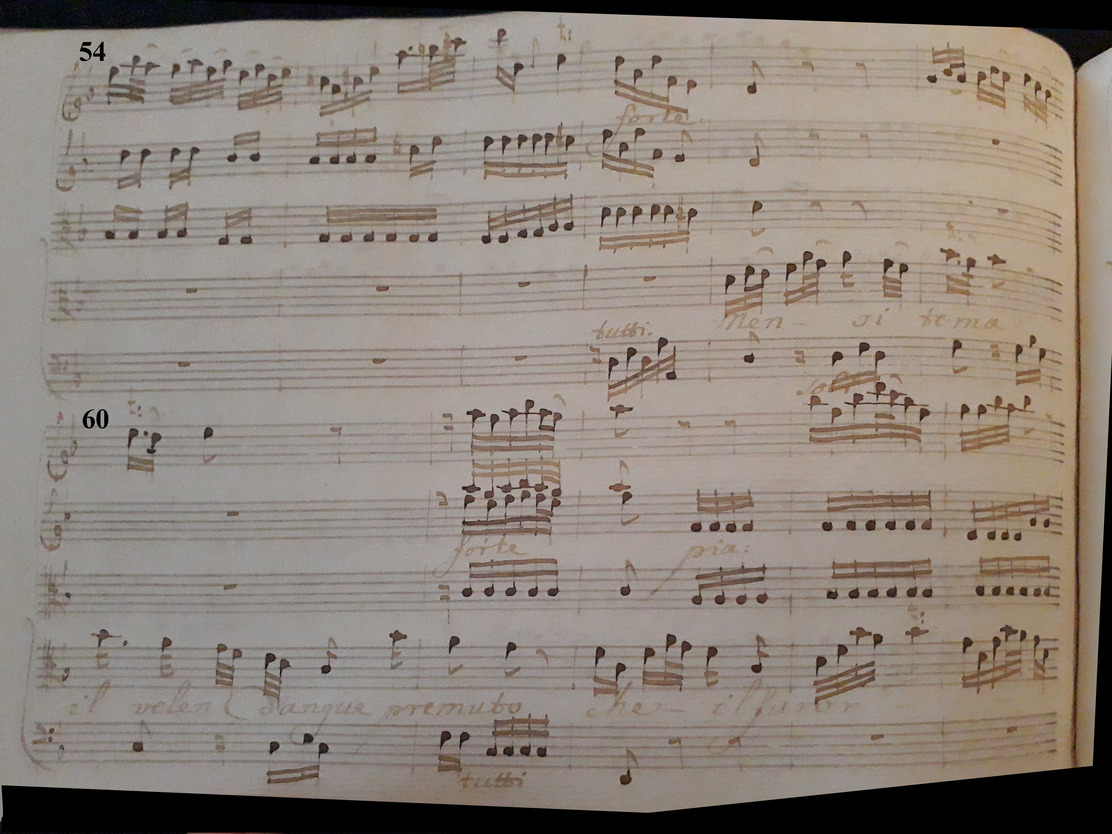

This aria requires a "violino solo concertante" accompanied by a concerto grosso of violins, viola and basso continuo.

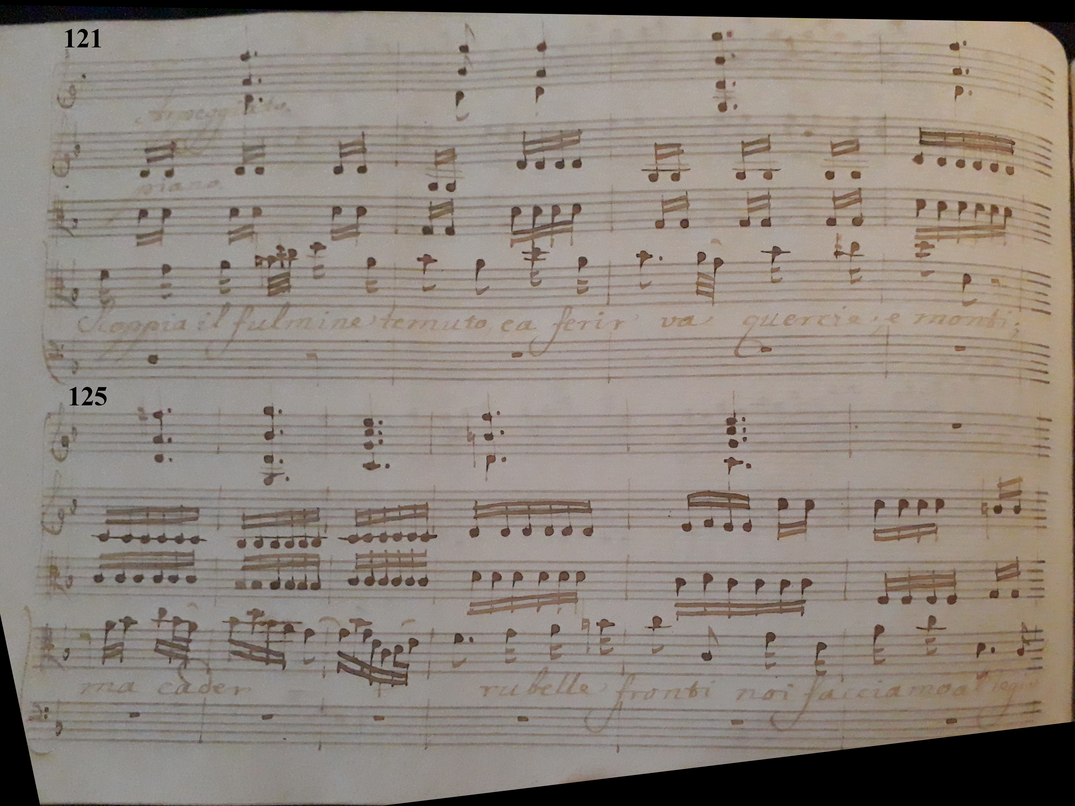

In this aria, Athalia sings of the anger of Joaz, her grandson and future king, whom she wanted to eliminate as a young child.

The allegro linked to the 3/8 as well as the sixteenth and thirty-second notes gives an impression of speed and haste which illustrates the text well.

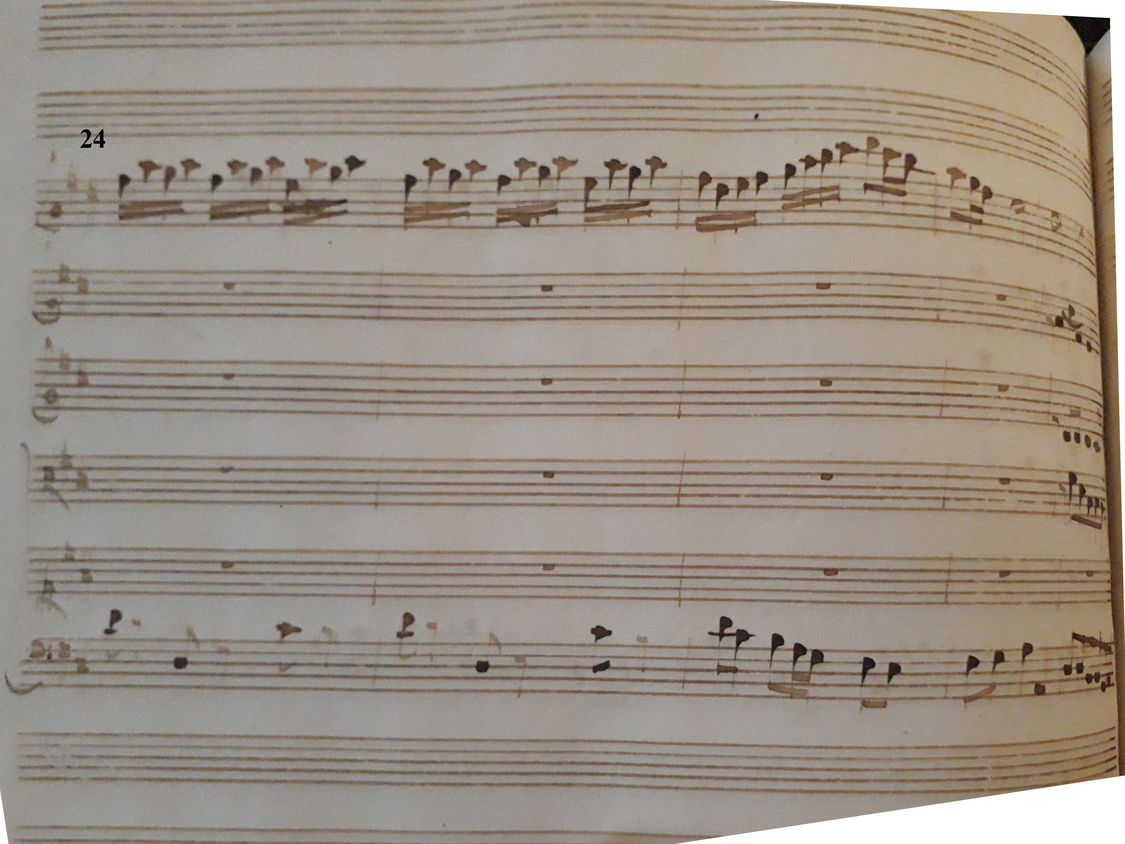

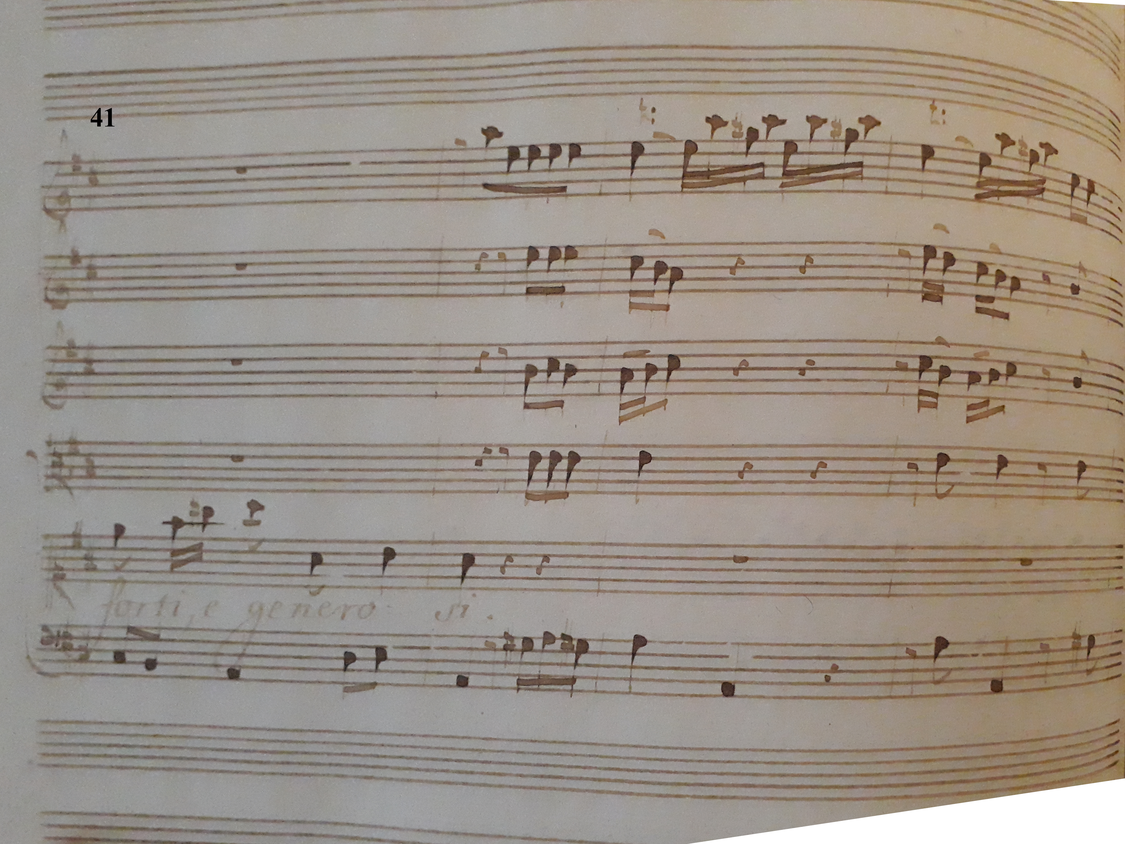

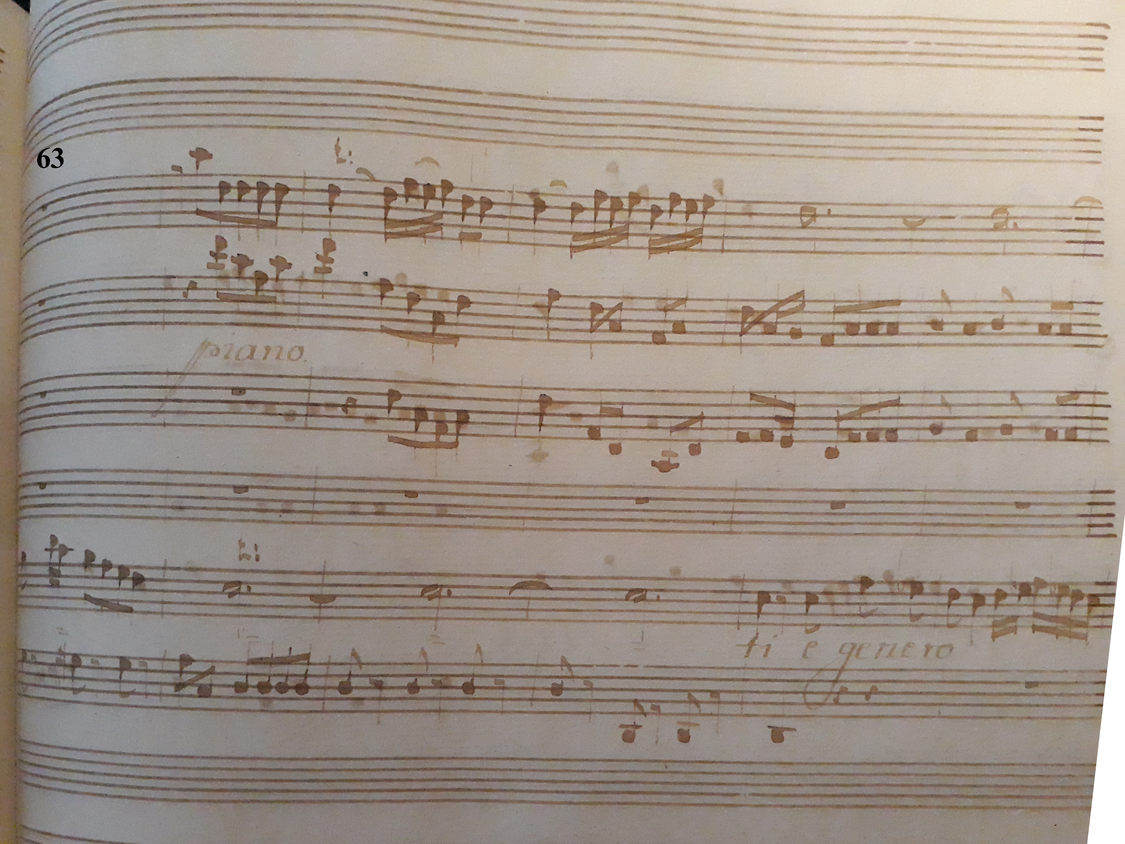

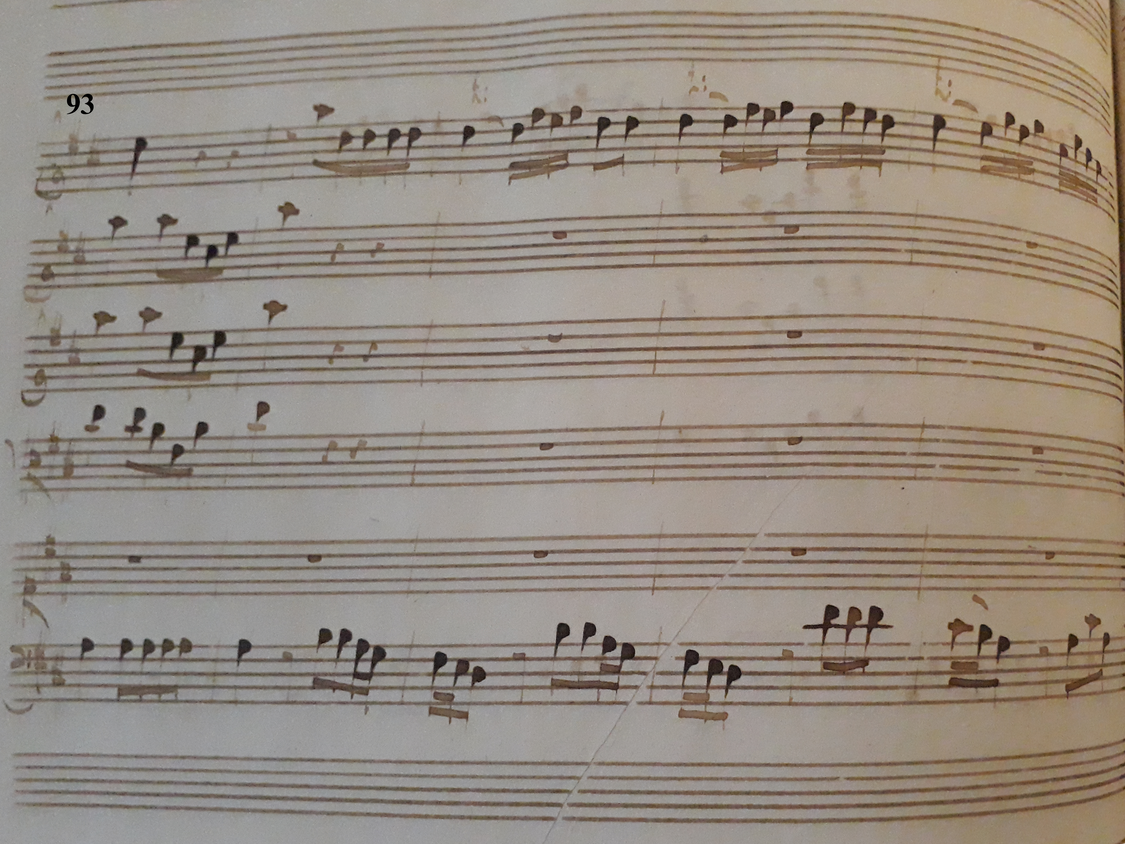

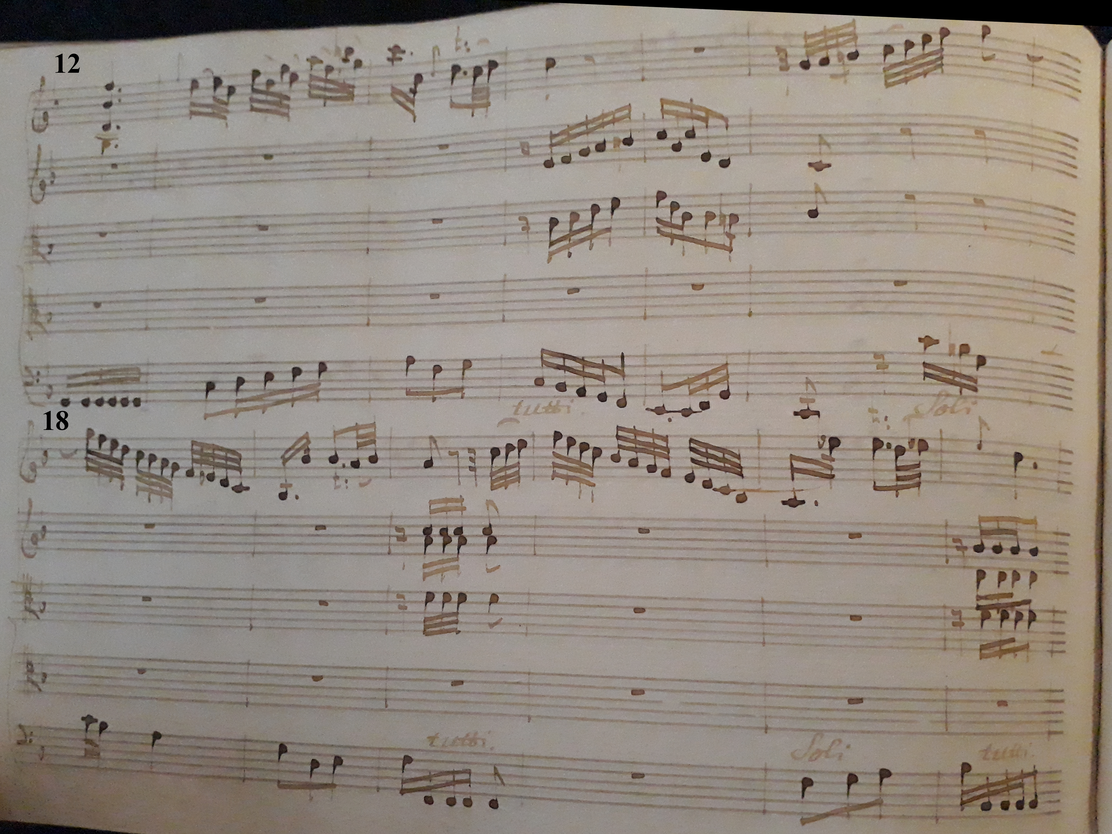

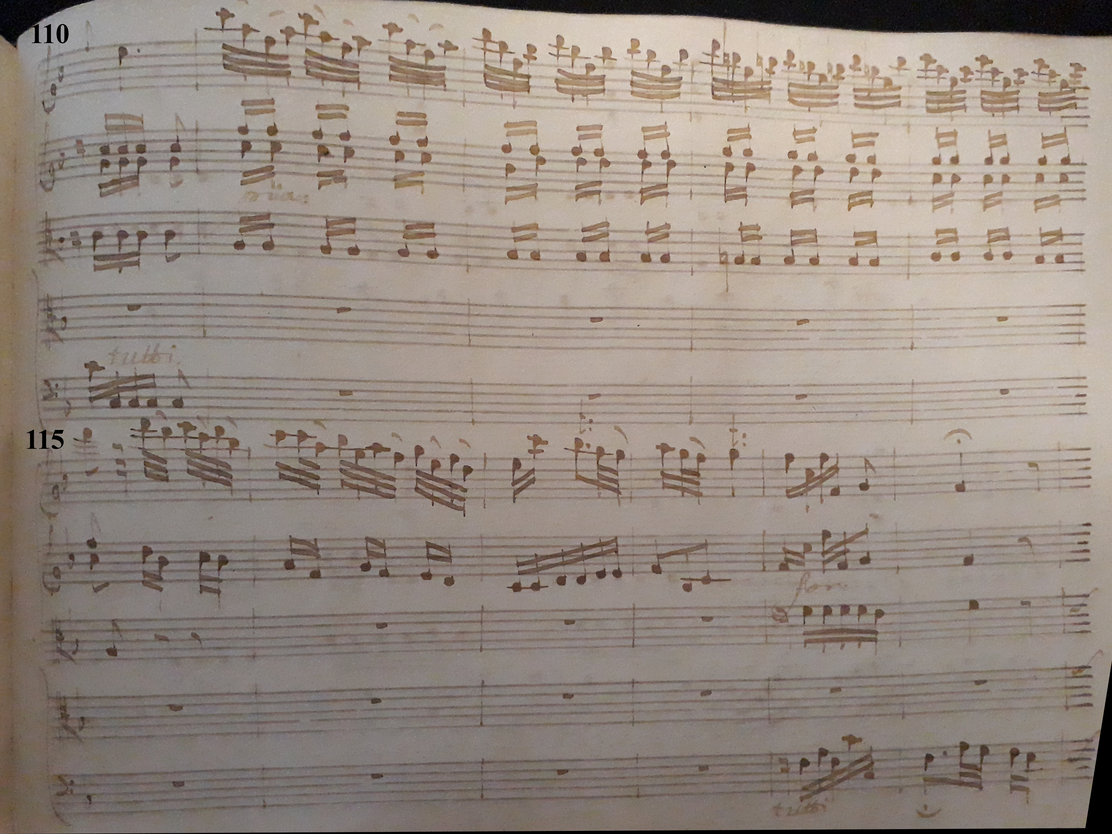

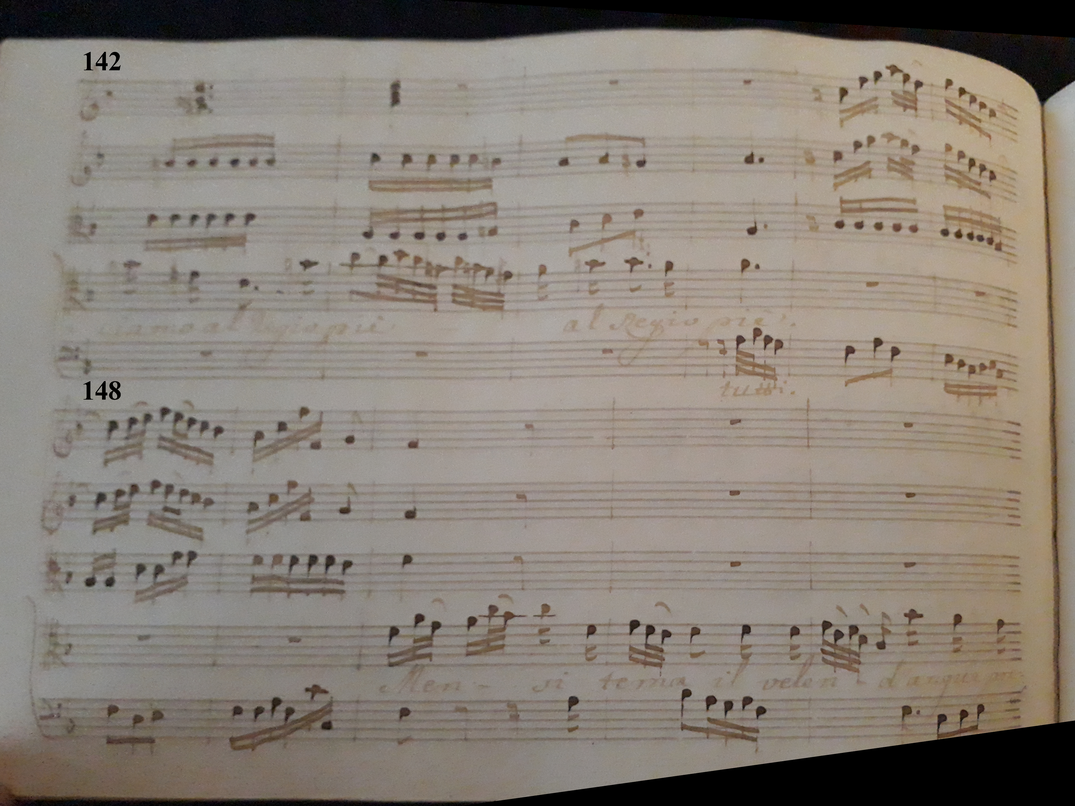

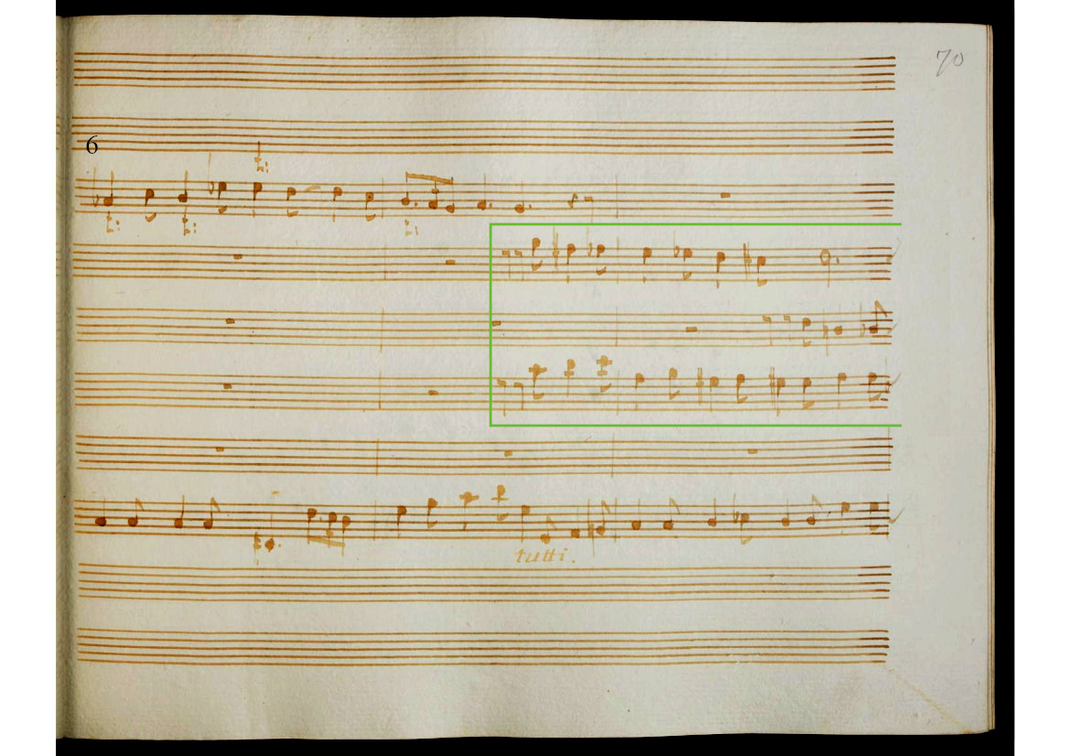

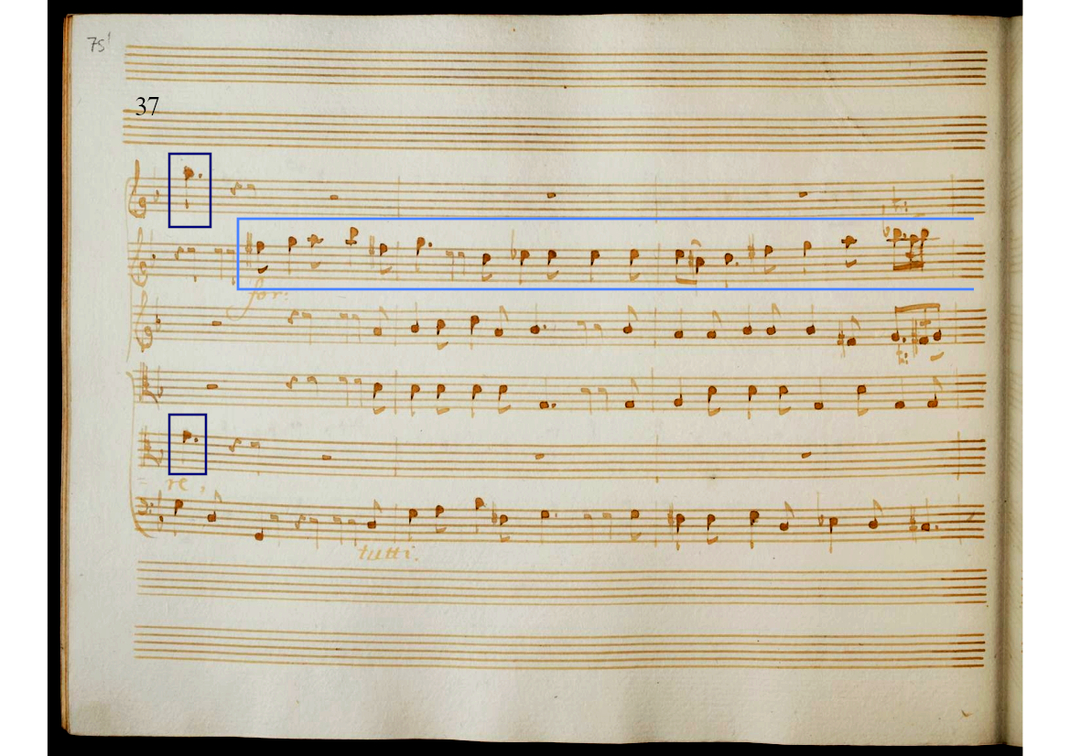

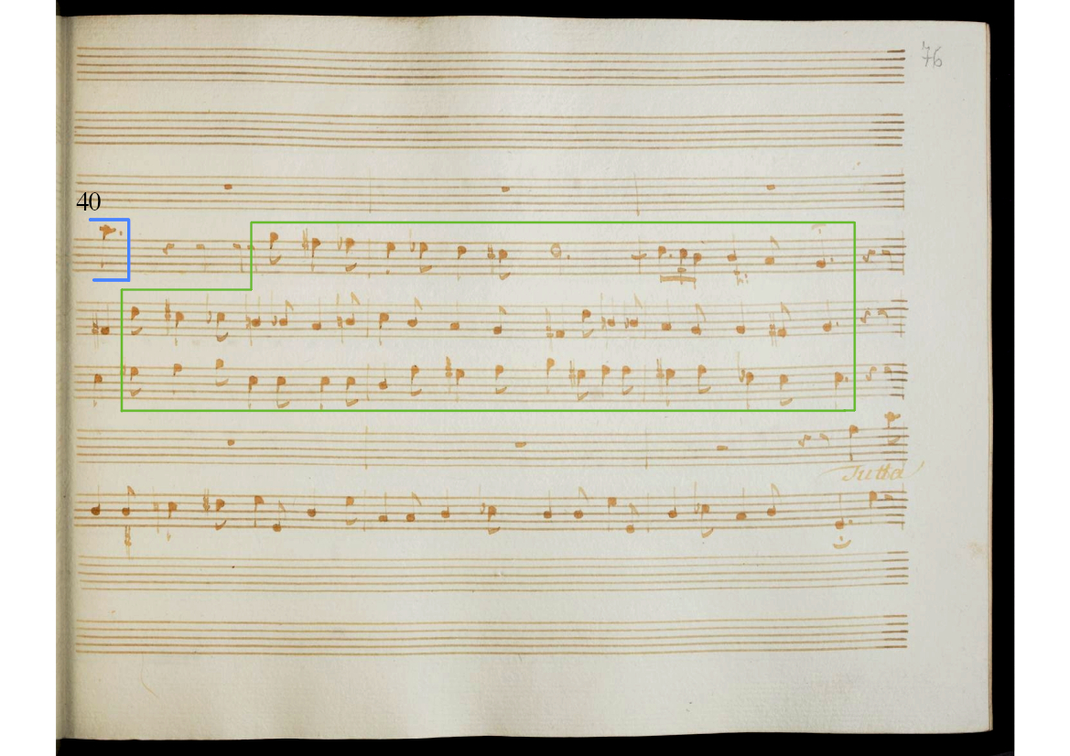

The aria begins with an instrumental introduction built around an alternation between solo violin and concerto grosso up to bar 11. From bar 12 onwards the solo violin is truly soloist with only a few very short interventions from the concerto grosso and viola. From 26 and after several cadenza formulas, the solo violin seems to accelerate the rhythm by thirty-second notes arpeggios to the cadenza of Athalia's entrance at bar 36.

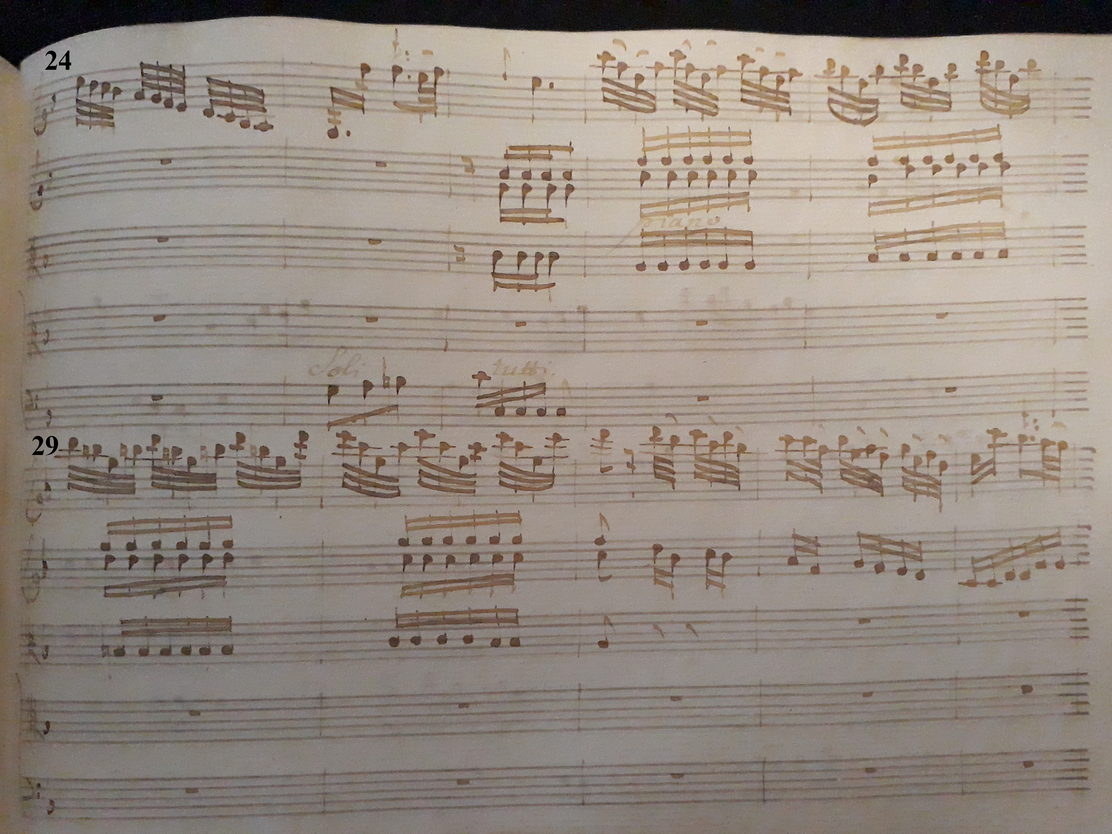

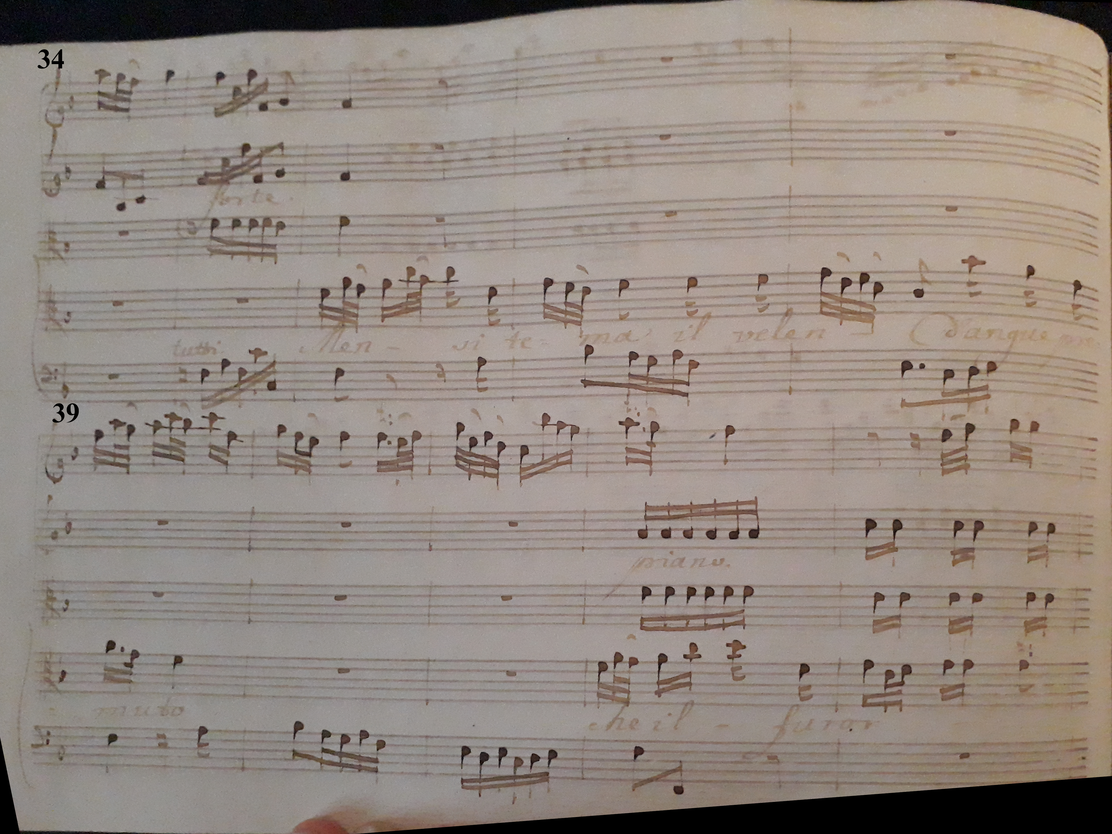

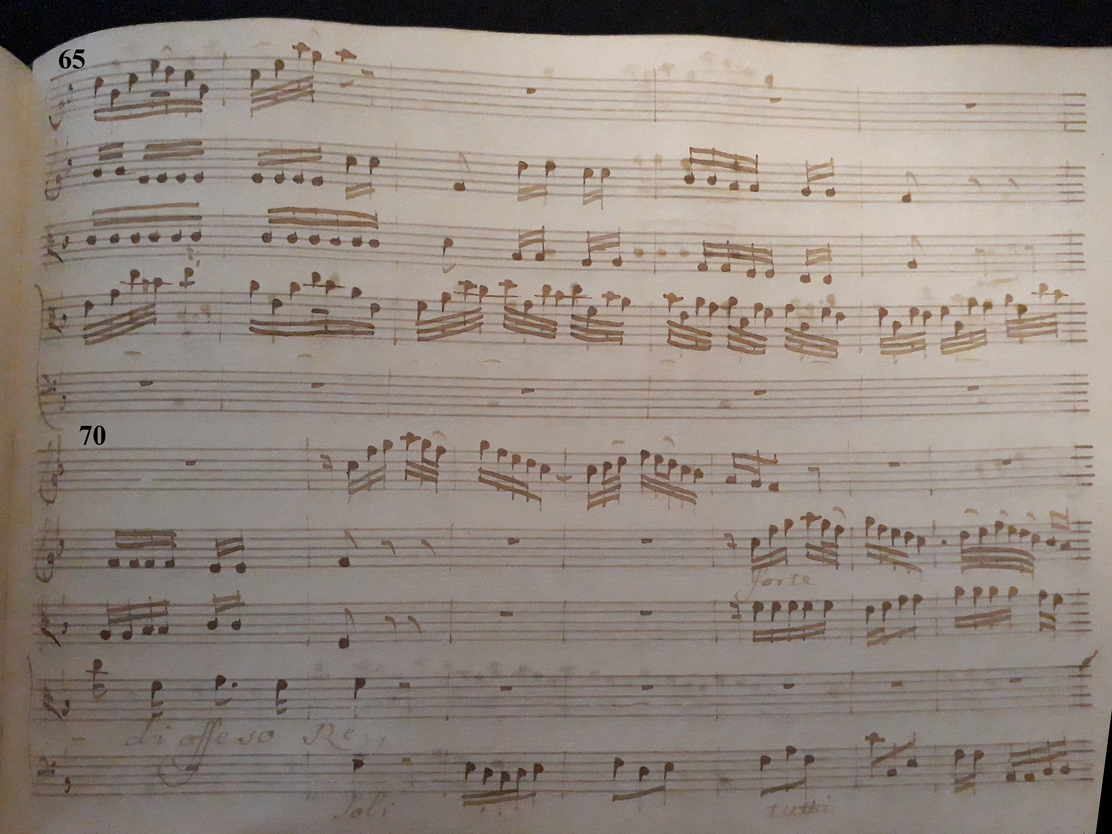

Here the voice exposes the first part of the phrase alone with the basso continuo: "mensi tema il velen d'angue premuto". It is joined on the cadenza by the solo violin and finally by the concerto grosso et viola on the second part of the phrase: "che il furor di offeso Rè". Here the basso continuo disappears, and the voice and instruments (solo violin, concerto grosso and violas) combine in the long vocalization of the word "furor" (fury) from bar 43 to the cadenza in bar 53.

While the concerto grosso and violas accompany harmonically, the solo violin imitates Athalia's phrases. Athalia alone concludes the vocalization and exposition of the text.

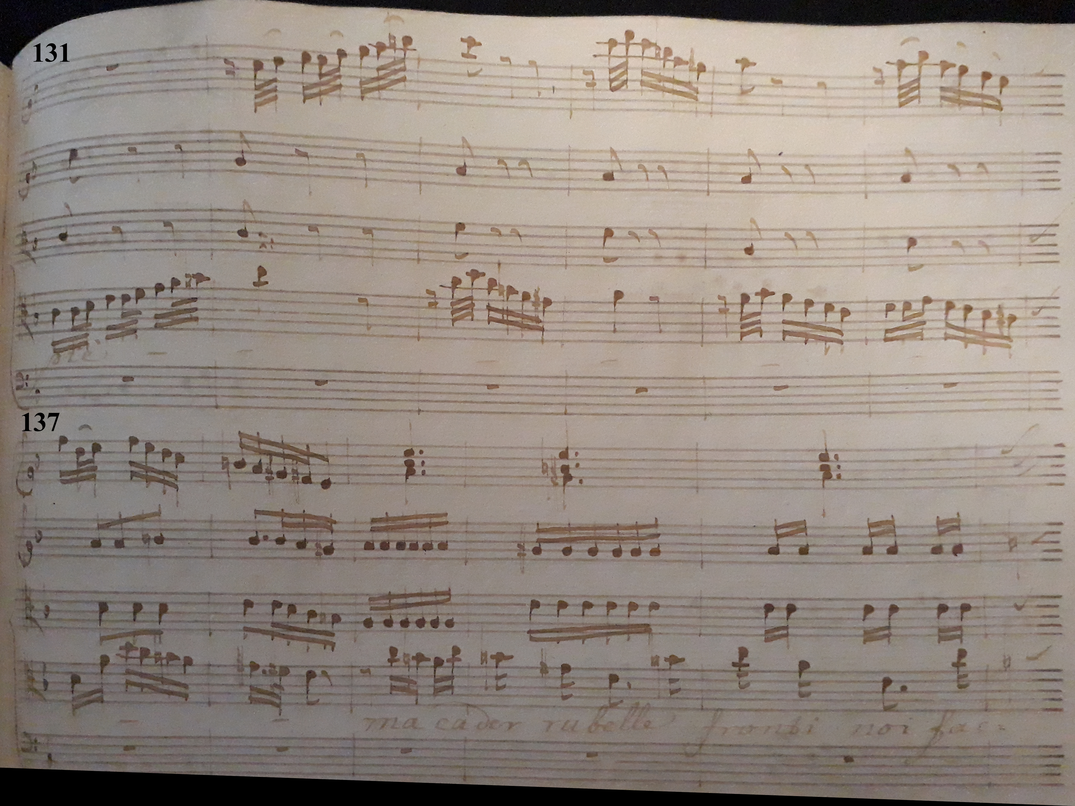

The chorus of strings without the basso continuo then follows with a short ritornello repeating the end of the sung vocalization and introducing the second exposition of the sung text at bar 58.

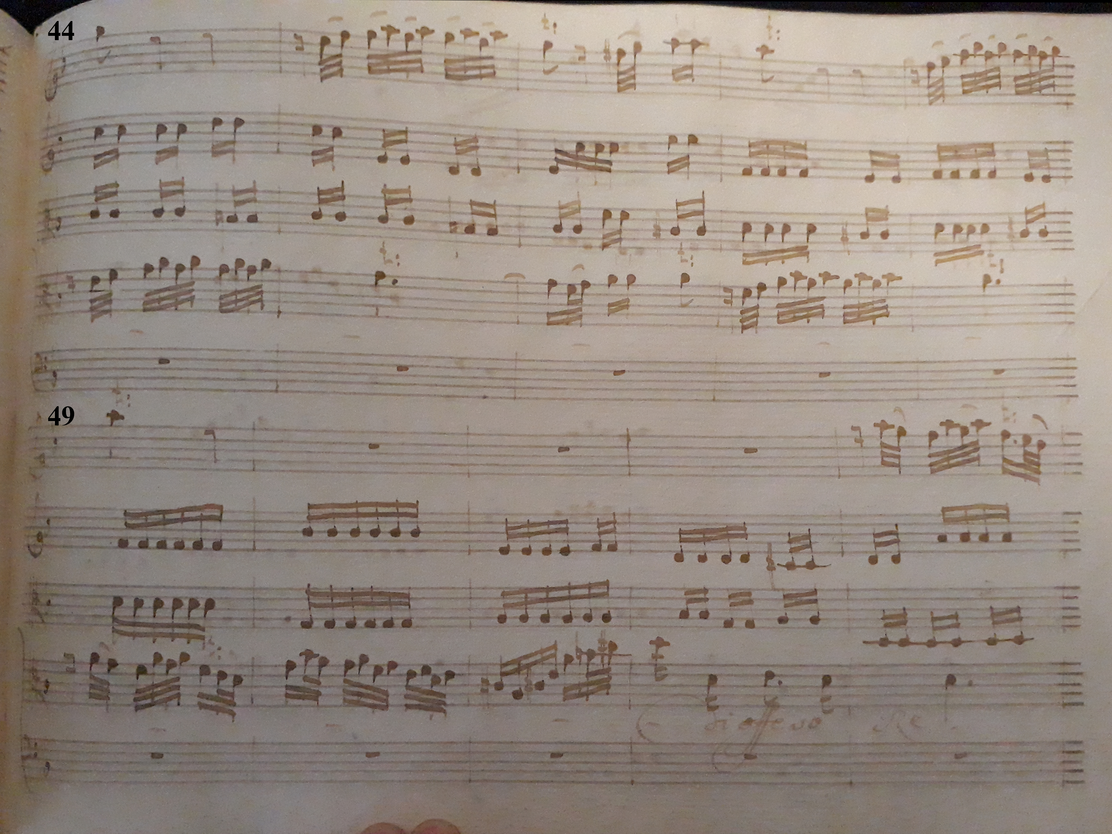

Here, the solo violin responds to the voice from the first part of the phrase. Then the same thing happens for the second part and vocalizes it on "furor": without BC, with the solo violin in imitation of the voice and the concerto grosso and viola in accompaniment. At 67, the solo violin lets the voice finish the furor vocalization alone and reappears at bar 71 to repeat the introductory motif of the aria over 4 bars and taken up again by the concerto grosso.

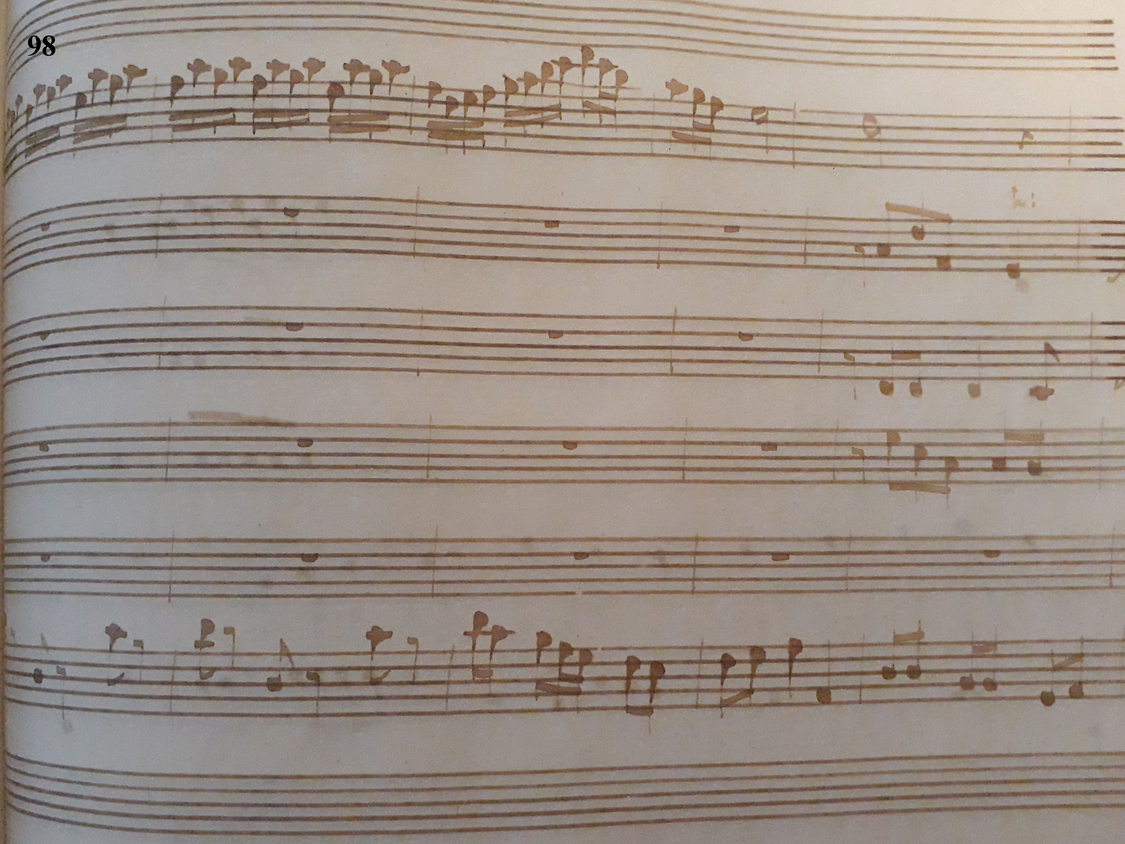

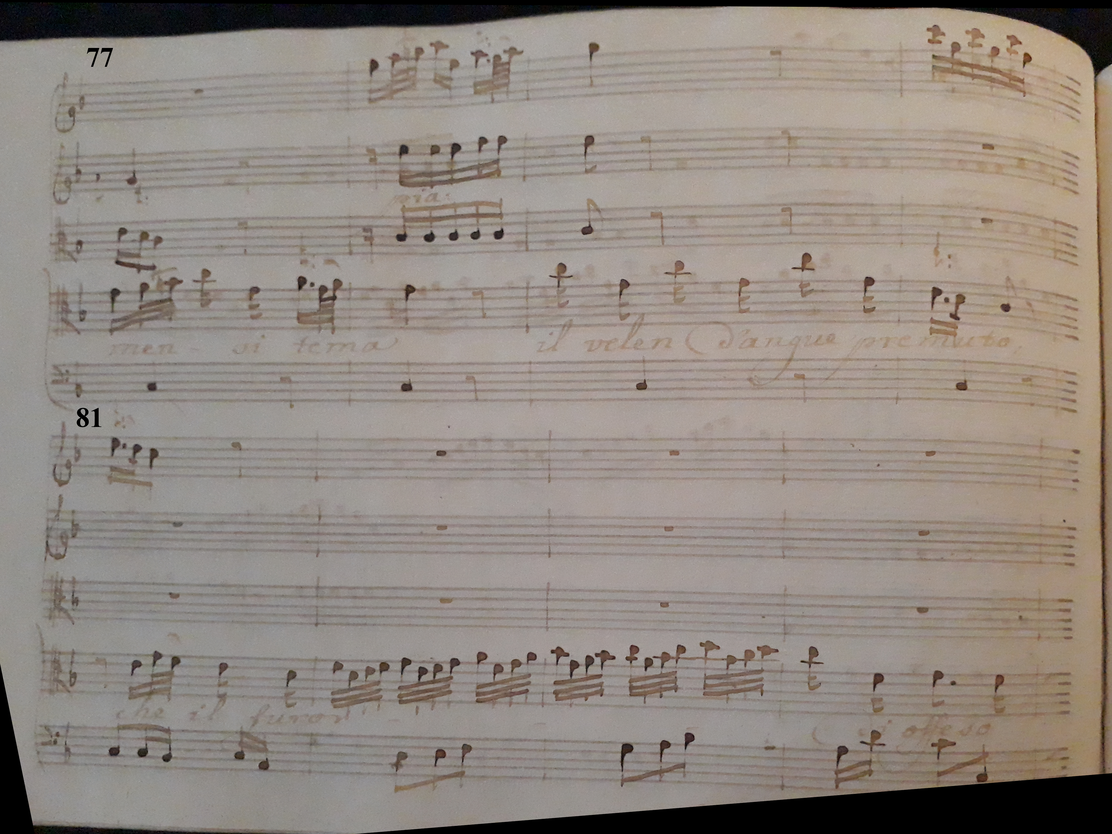

At 77, Athalia begins the third and last exposition of the text, this time she is almost alone with the basso continuo and a few very short interventions by the high strings. It is as if the text here takes on an even greater dimension through its nudity. The vocalization on "furor" is much shorter than the two previous times (only 2 bars).

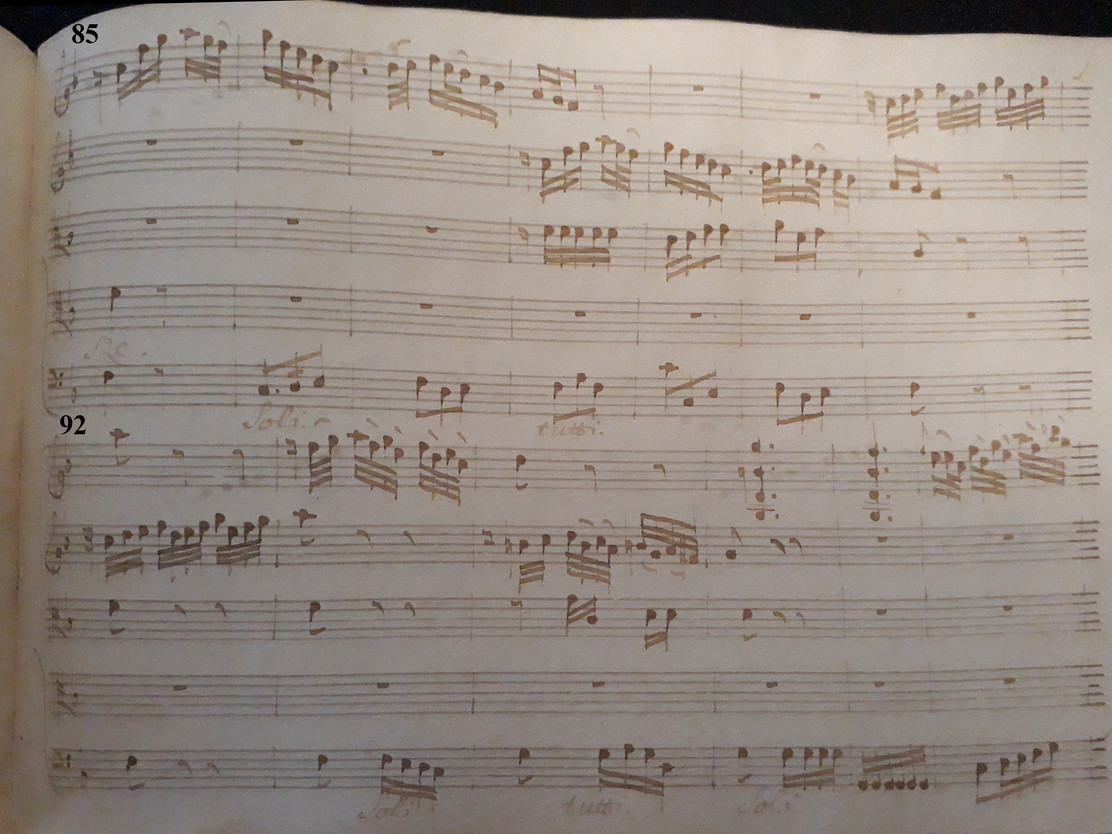

At cadence bar 85, the instruments repeat the instrumental ritornello from the introduction of the aria in an identical manner up to cadence bar 116.

The B part is much shorter than part A with only one exposition of the text. The basso continuo does not accompany the upper instruments and the voice, leaving them to form a chorus.

The concerto grosso and violas accompany in repeating sixteenth notes, while the solo violin plays chords up to bar 129. At 131, Athalia begins a vocalization on the word "piè" (foot), during which she is almost naked with the solo violin imitating what she does. At 137, the instruments join the voice again with sixteenth notes and chords for the solo violin until the end of the middle section at bar 145.

The solo violin is for me Athalia's little inner voice, a reflection of her fear and an expression of the anger boiling inside her as she is about to be sentenced for her crimes. The dexterity of playing on this instrument allows the appropriate speed for this kind of strong and even violent feelings. The sensation of speed given by the tempo and by the sixteenth- and thirty-second notes makes the emotional state in which Athalia finds herself quite clear to me. The solo violin does not necessarily play the melody being sung, but sometimes echoes and joins her on the most important words: "furor" and " piè".

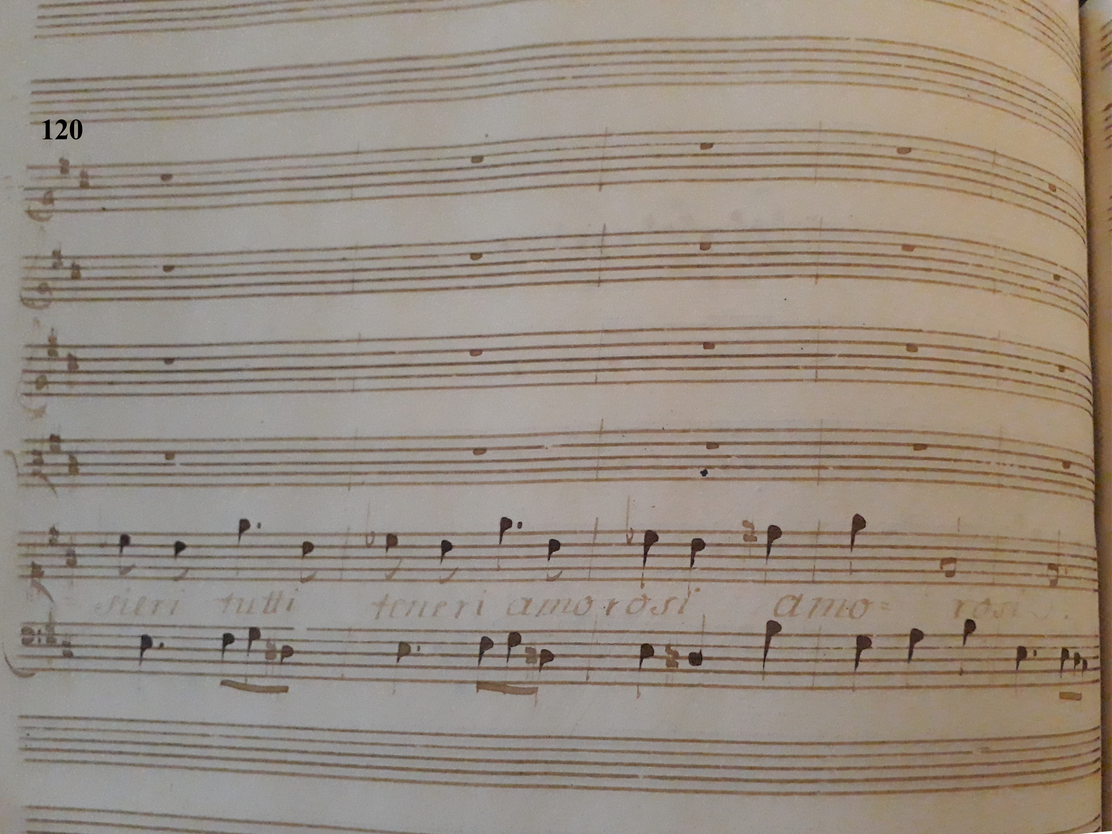

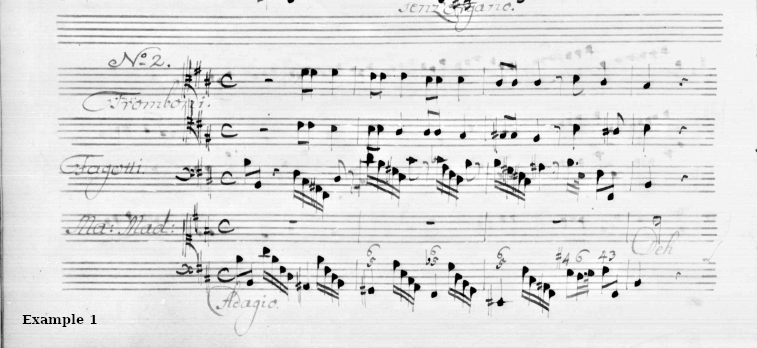

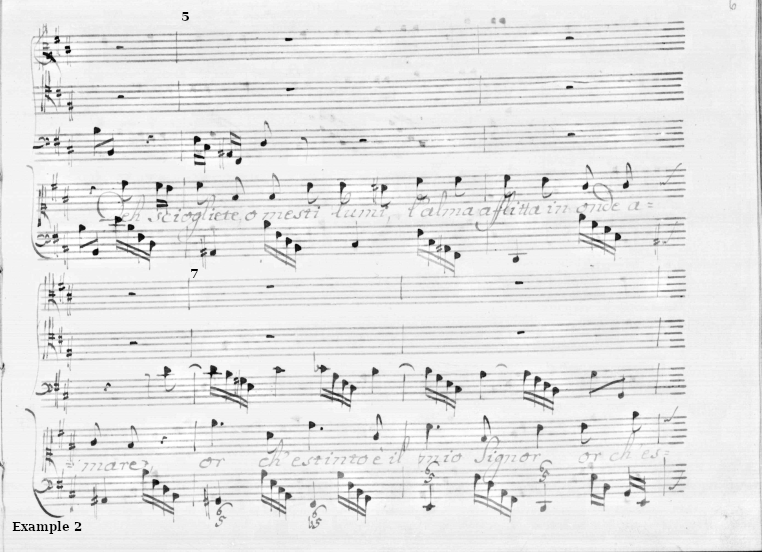

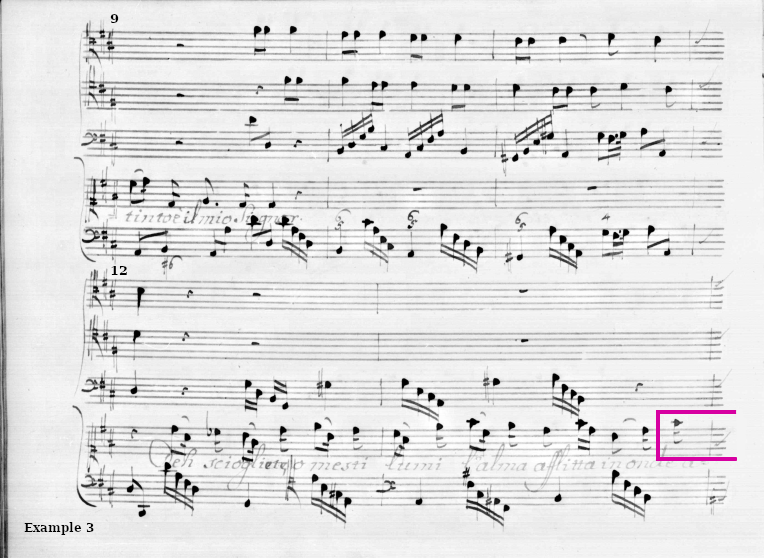

Death aria - analysed example: Maria Maddalena

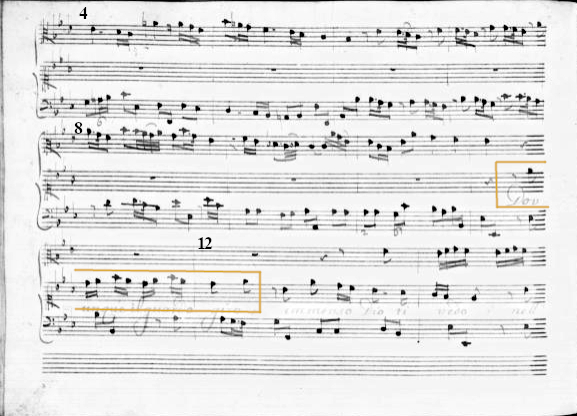

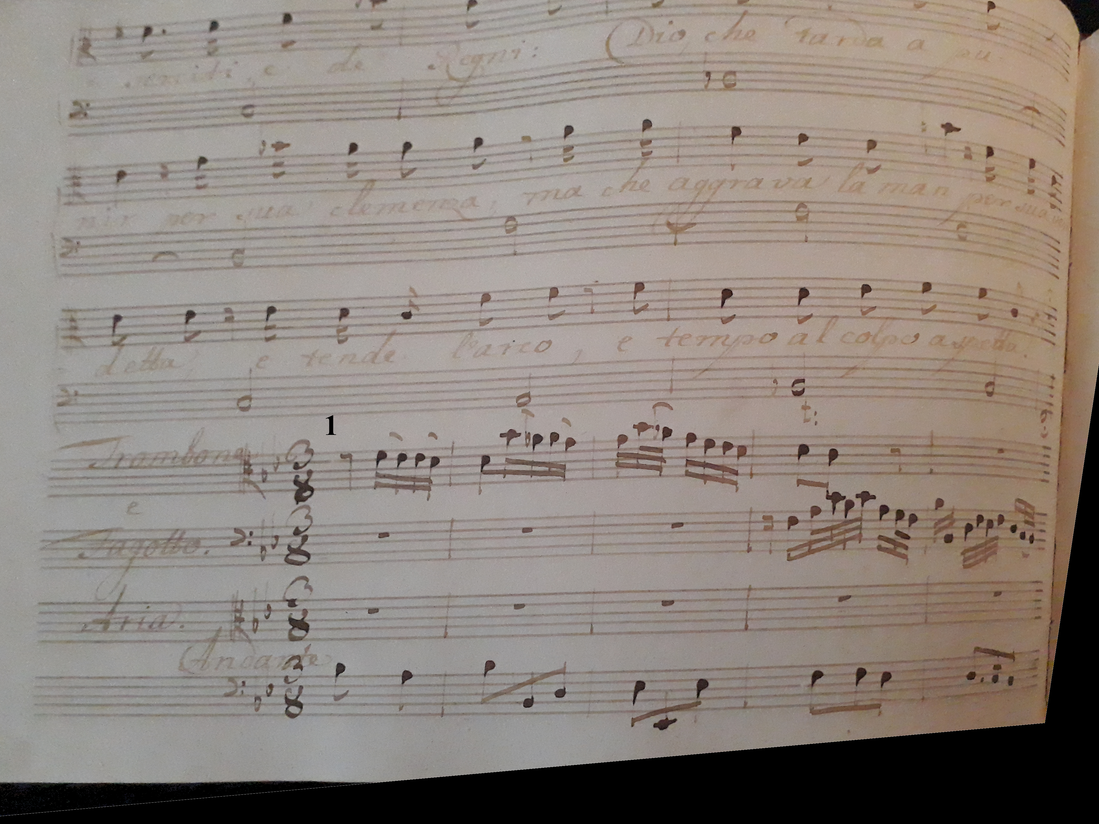

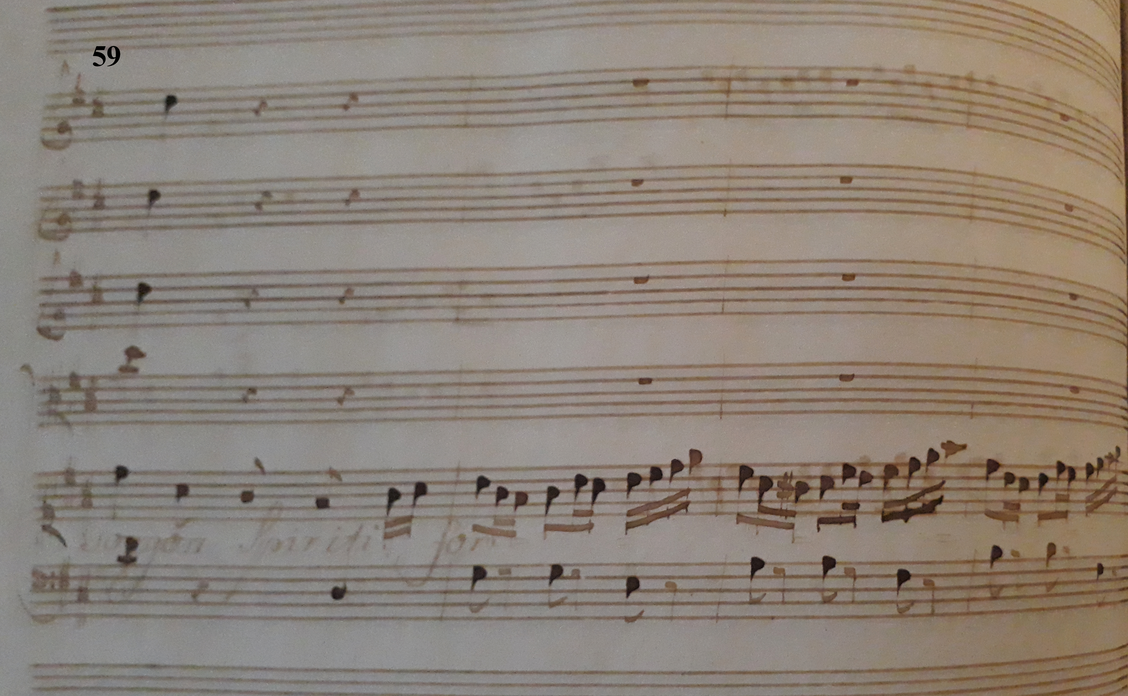

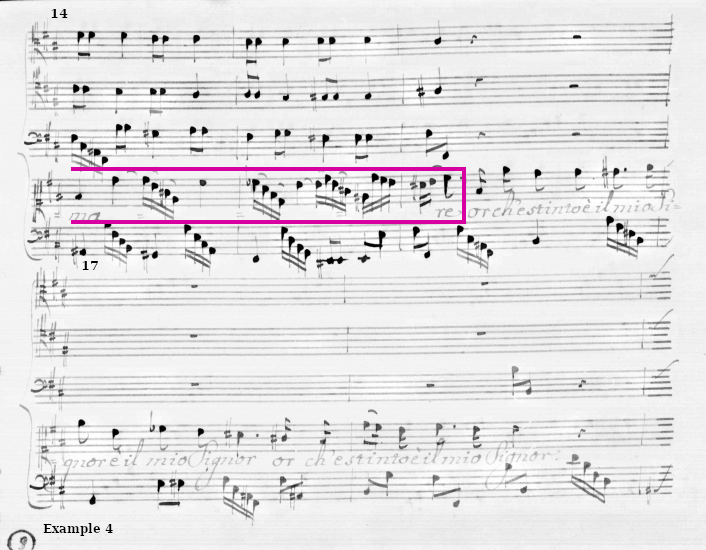

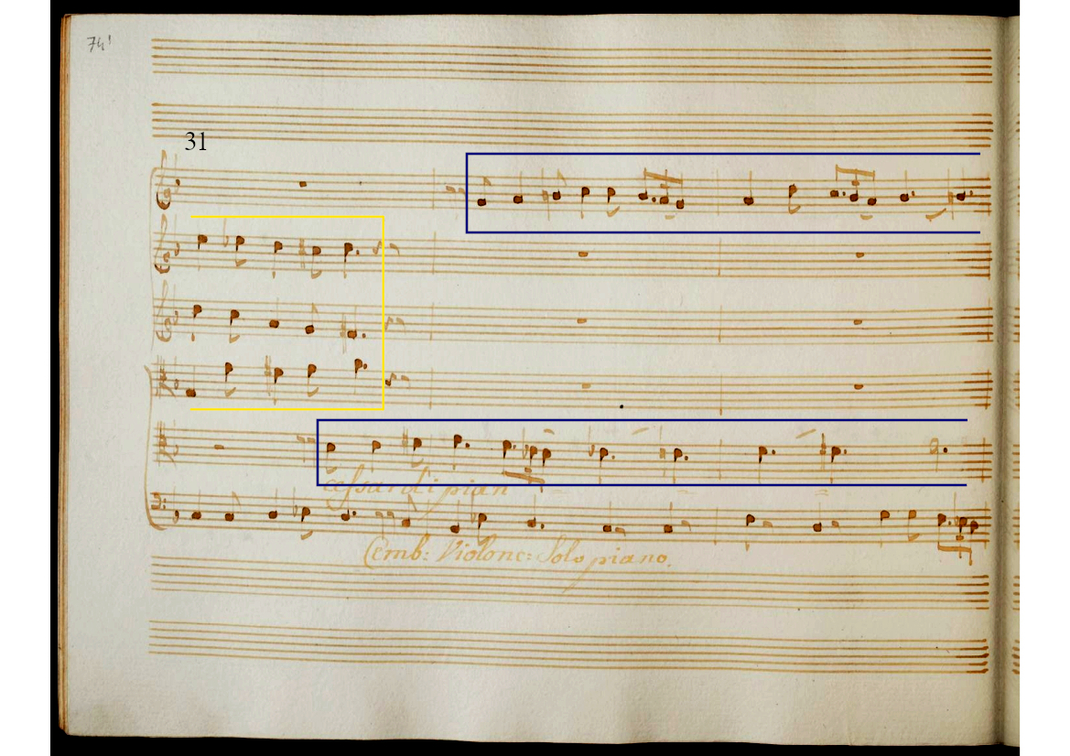

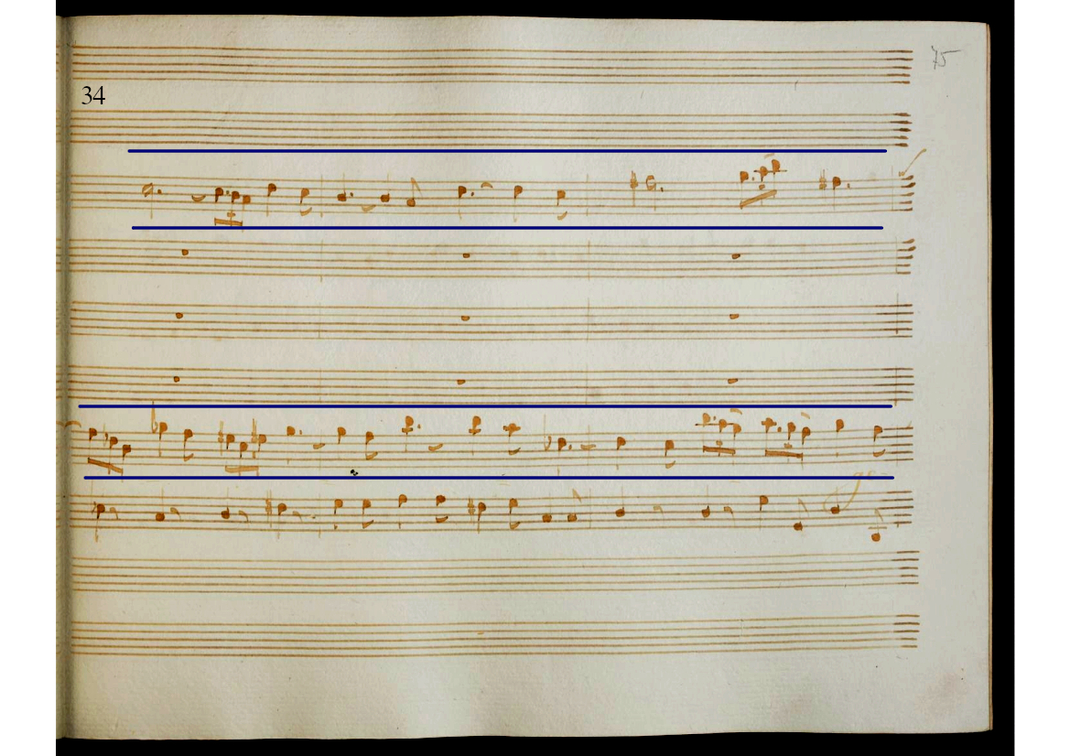

In Maria Maddalena's first aria in Morte e Sepoltura di Cristo, she is accompanied by two trombones and two bassoons (in unison). The instruments introduce the aria (ex 1) with a very short ritornello that sounds like a kind of funeral march. On the first part of the text "Deh sciogliete, o mesti lumi, l'alma afflita in onde amare", Maria Maddalena sings alone, joined by the bassoons at bar 7 (ex 2) for the first exposition of the rest of the text "or ch'estinto è il mio Signor", and again alone from its repetition (ex 3) to the cadenza. Here we find the trombones and bassoons for a short instrumental interlude close to that of the beginning of the aria.

For the second exposition of the text from bar 12 onwards (ex 3), the bassoons enter directly with the voice. They are joined by the trombones at bar 14 (ex 4) on the word "amare" (bitter) which extends in a long vocalise to bar 16. Then the soprano is again alone for the rest of the text and up to the cadenza at bar 18. The chorus of instruments (trombones and bassoons) enters from bar 19 and up to the end of part A of the aria at bar 21.

In the B part, the trombones and bassoons give place to the violins in unison. The violins accompany the voice throughout this part and up to the cadenza at bar 28. They keep the same arpeggiated sixteenth note rhythm.

In this aria, the instruments do not have a melodic role that sustains that of Maria Maddalena. Instead, they seem to create a carpet of sound that contributes to the funereal atmosphere of the piece.

Here, too, the first exposition of the text is left to the voice alone, in order to make it well heard. The second exposition of the entire text from bar 12 onwards is accompanied from the beginning by the bassoons, and even enriched by the presence of the two trombones on the word "amare" (bitter) as if to emphasise the bitterness of her situation. This is the only moment in the aria where we have a tutti, as a kind of sound and harmonic climax of the aria.

The obbligato instruments are therefore related to the affects present in the text, they translate here a particular atmosphere and seem to intervene on the important words of the text (such as "amare") in order to highlight them.

Caldara's writing for these two instruments here creates a solemn and funereal chorus that sustains Maria Maddalena's pain throughout the piece. Neither of the two instruments ever plays the melody carrying the text, on the contrary they are like a sound and harmonic carpet that translates the atmosphere present in the text, that highlights the affects of sorrow, pain and death.

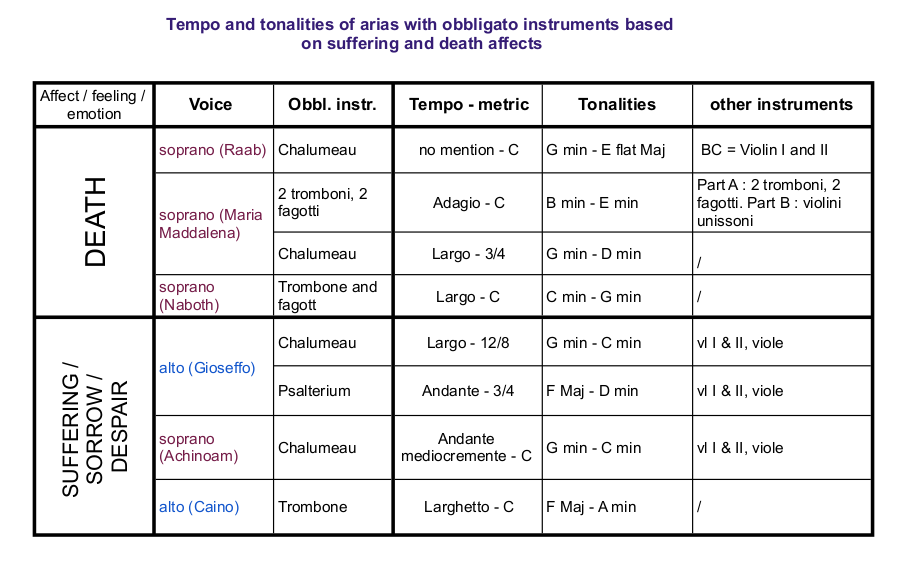

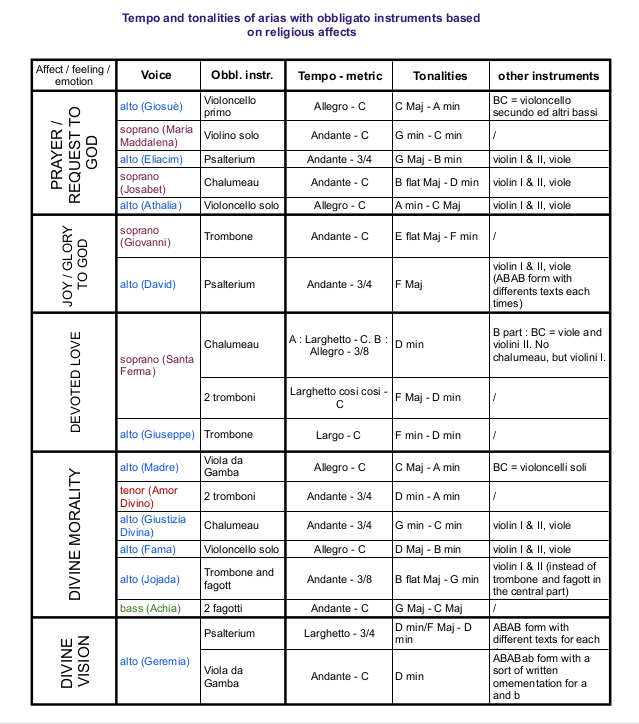

At first glance, this category being very broad, it may seem difficult to find recurrences in the attribution of certain instruments to certain affects. However, we have seen that we can highlight certain things.

-

The prayer category is mainly attributed to the strings (4 out of 5 arias).

-

The category of divine morality is mainly attributed to the winds (4 out of 6 arias).

-

The arias in the category of devout love are for trombone (2) and chalumeau (1).

-

Half of the arias in this category are attributed to winds, the other half to strings.

In the table above, we can see that 11 of these arias are for alto, 5 for soprano, 1 for tenor and 1 for bass.

This does not mean that this category of affect is more suitable for the alto voice, but simply that the characters with these arias were mainly attracted to the alto voice by Caldara.

Devoted love aria - analysed example: Santa Ferma

In the oratorio Santa Ferma, this aria is the last of the first part and the third that Santa Ferma sings.

In it she expresses her love for God and the torments and sorrows she is willing to endure in order to please him. This painful and languid devotion is in perfect harmony with the chalumeau.

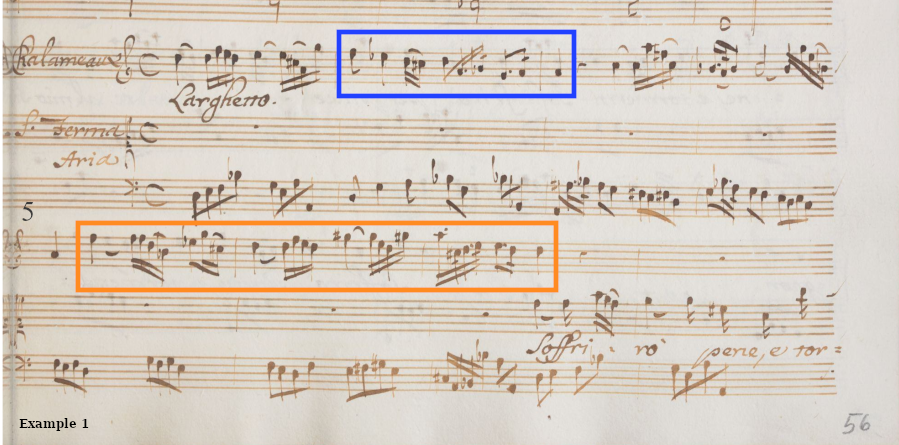

At the beginning of the aria we can notice in example 1 that the obbligato instrument introduces the aria with the same melody which will then be sung by Santa Ferma. The chalumeau plays a kind of ritornello that includes all the melodic elements of the air, which is then taken up by the voice.

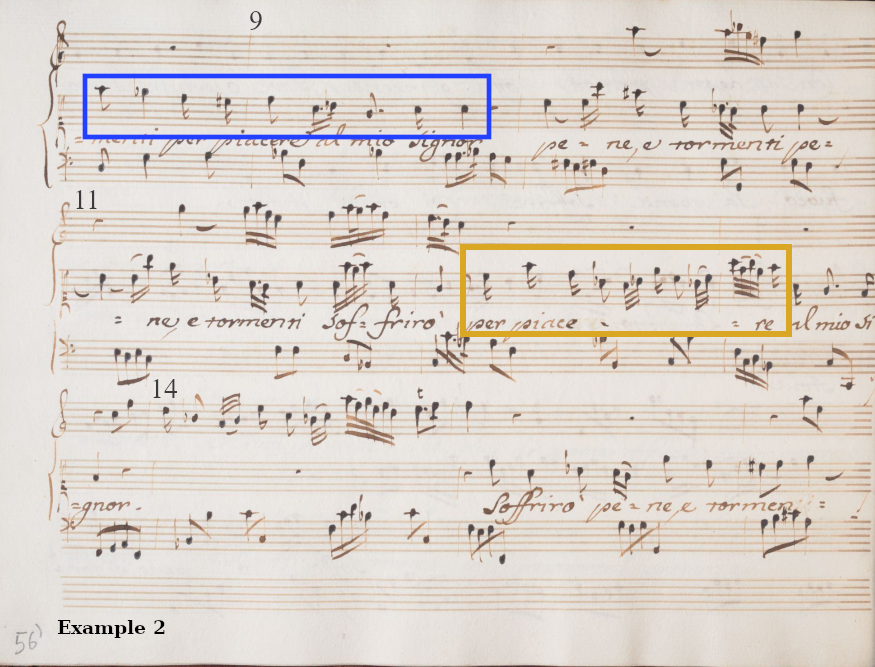

In example 2, it can be seen that the chalumeau leaves the entire space to the voice for the first exposition of the text and then enters again for its first repetition until the following cadenza. The soprano is then alone in the vocalization on the word "piacere" (to please) until the cadenza where the chalumeau continues with exactly the same melodic line.

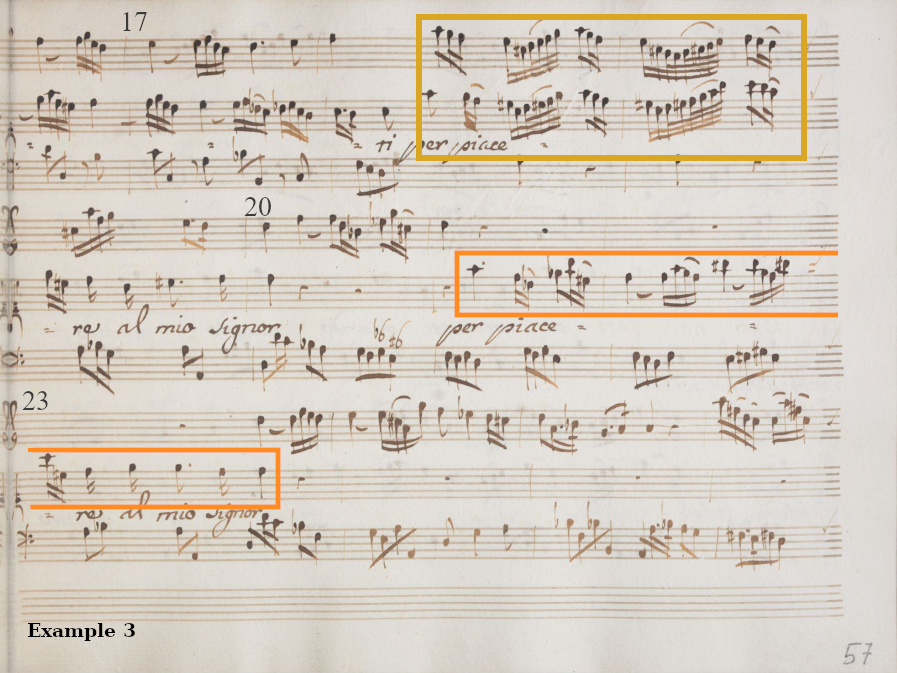

For the third exposition of the text "Soffrirò pene e tormenti per piacere al mio Signor", the voice and the chalumeau join together from "tormenti" and up to the cadenza (example 3), after having vocalized together, and even faster than in example 2 on the word "piacere". The voice then finishes alone the 4th repetition of "per piacere al mio Signor" (to please my Lord) before the chalumeau continues with the ritornello at the end of part A (examples 3 and 4).

In the B part, the chalumeau and basso continuo give way to violin 1 above, and violas and violins 2 on the bass.

Melodically speaking, rich chromatic lines are Caldara's "trademark". They can be found in most of the arias of complaint or pain, as here in bars 2 and 5 with the chalumeau (ex 1), and in the voice in bars 8 (ex 2) and 21 (ex 3) respectively. From the opening ritornello, the chalumeau thus announced this expressive chromatic motif which serves as the vocal conclusion of part A.

In this aria, the chalumeau, in my opinion, has a role both as a precursor and as an echo of the pain sung by Santa Ferma. After somehow "announcing the colour", he leaves the voice naked for the first exposition of the text, which for me is a clear indication that it must have been perfectly audible at that moment. As the text repeats, the chalumeau joins the voice to finally transform itself into its double, its shadow on the penultimate exposition (ex 3). Finally, the sung aria ends as it began, the voice exposes one last time, in a very rich harmonic and chromatic way, the last phrase of the text before the chalumeau concludes the air with the same ritornello.

The chalumeau thus echoes this sadness and pain while highlighting them. One might even think that its plaintive sound inspires the sung voice.

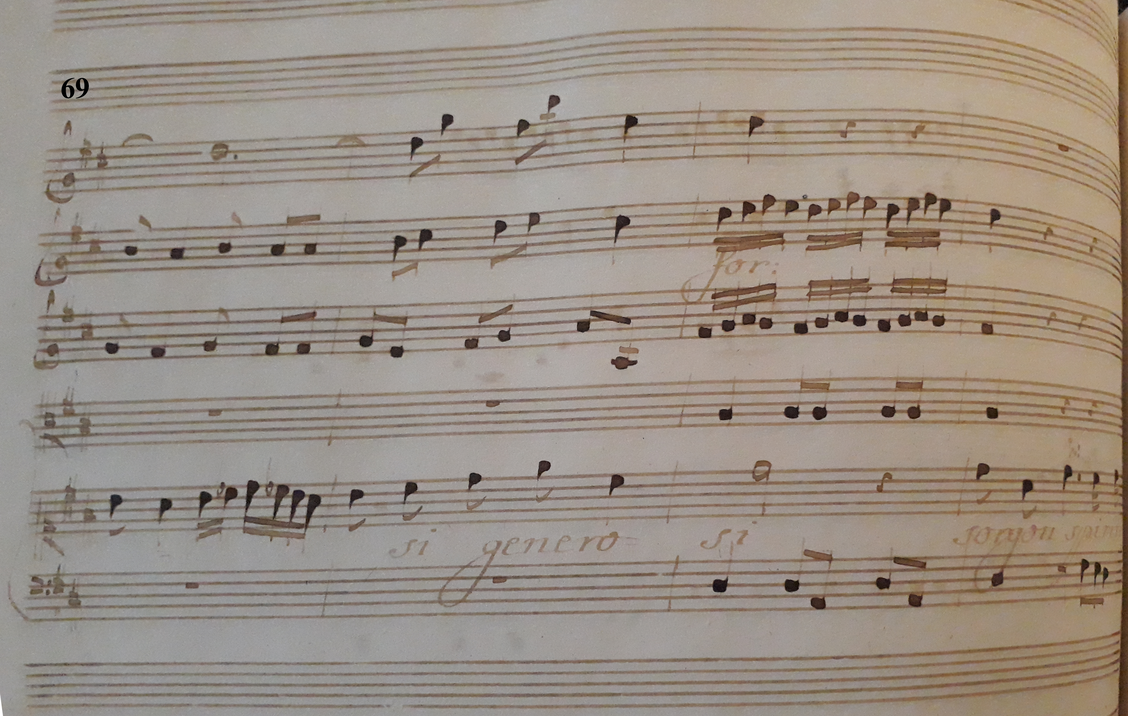

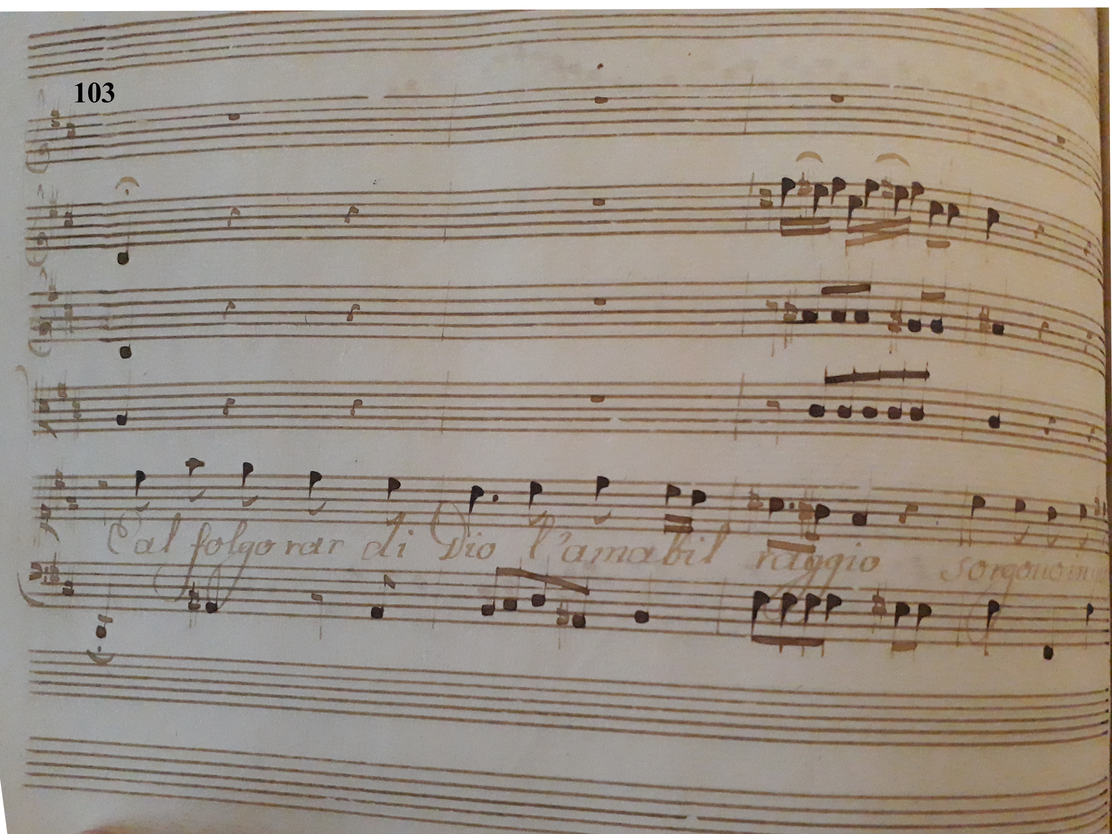

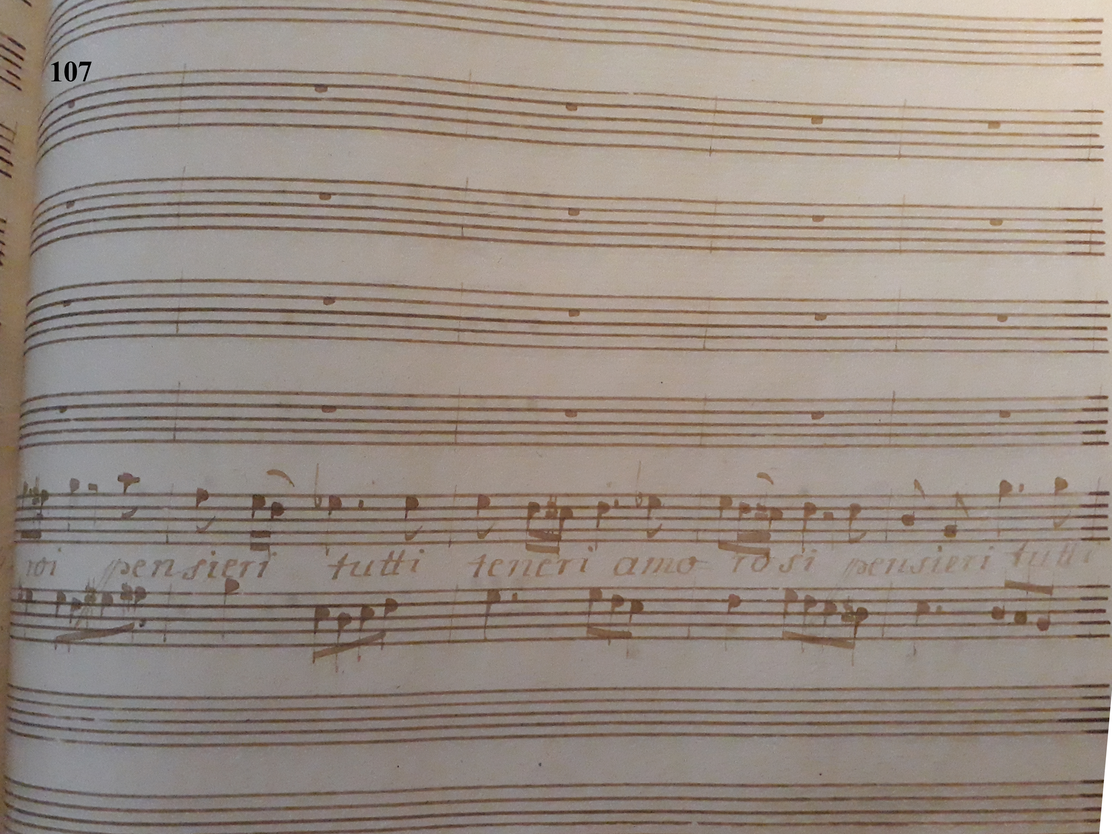

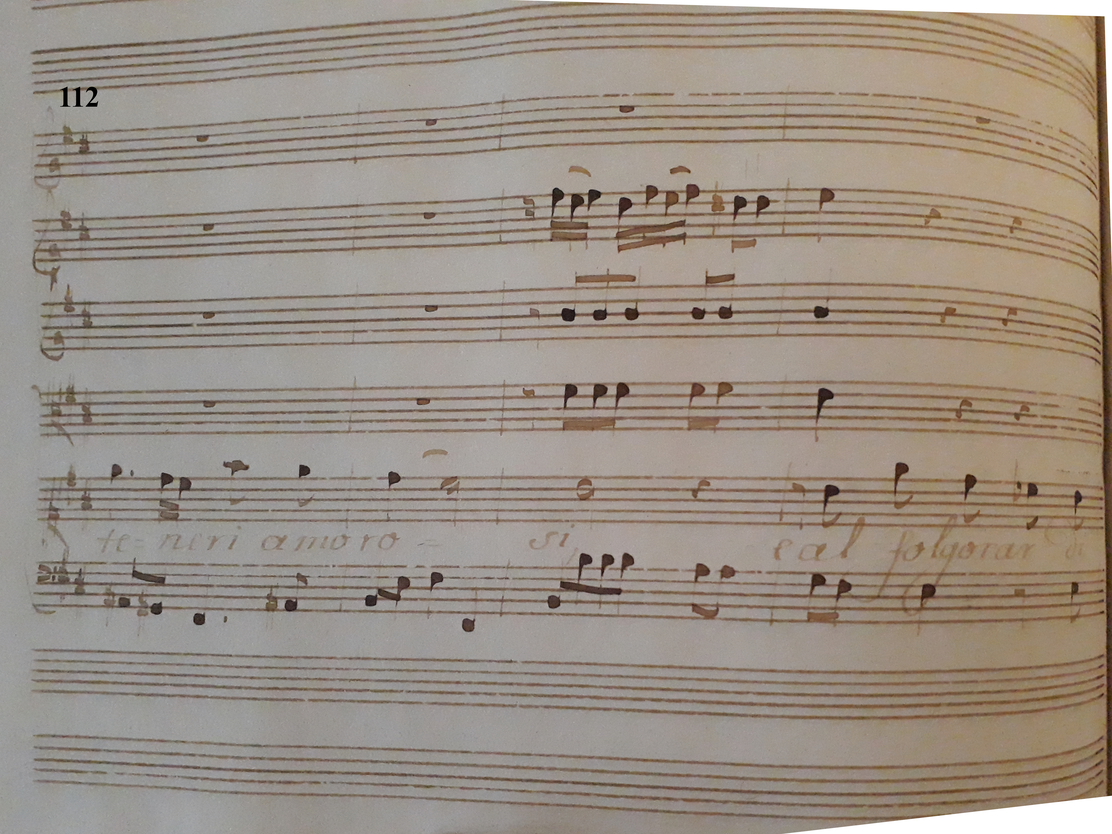

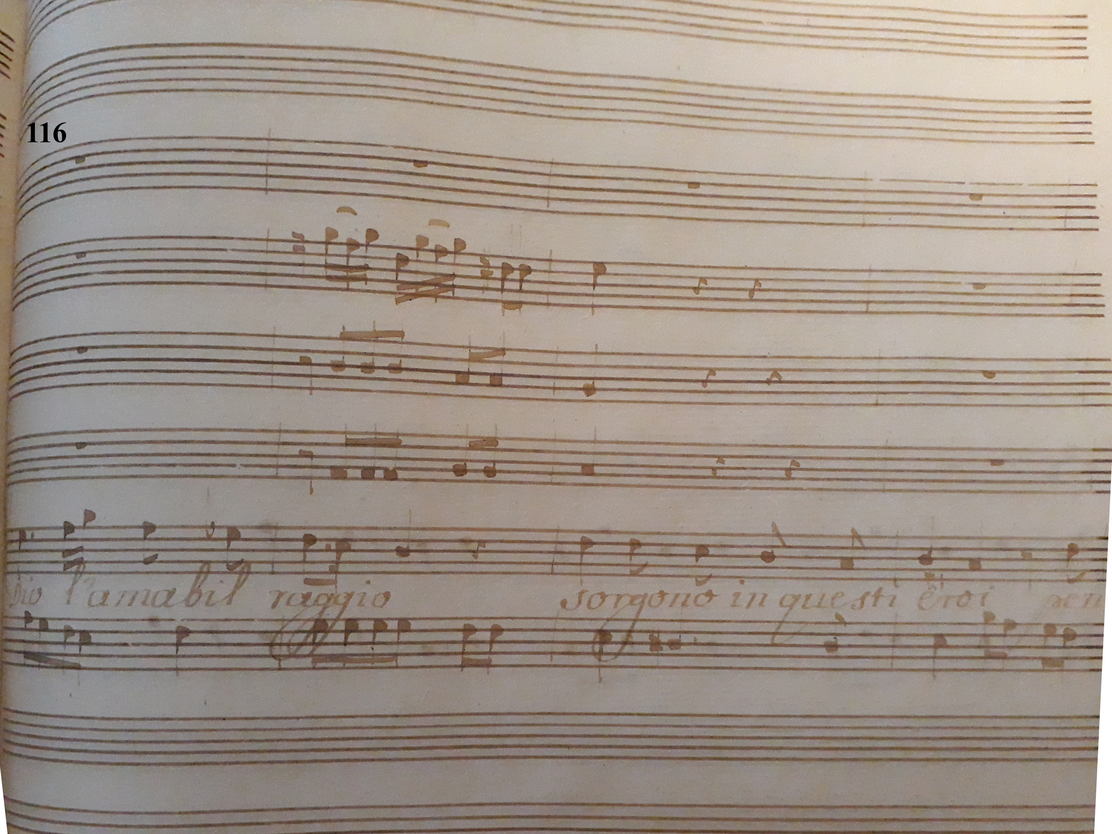

Warlike joy - analysed example: Onor Divino

The oratorio Il Trionfo della Religione is the only one-part oratorios written by Caldara in Vienna. The Onor Divino aria comes about three quarters of the way through the oratorio, it is the third and last aria sung by this character.

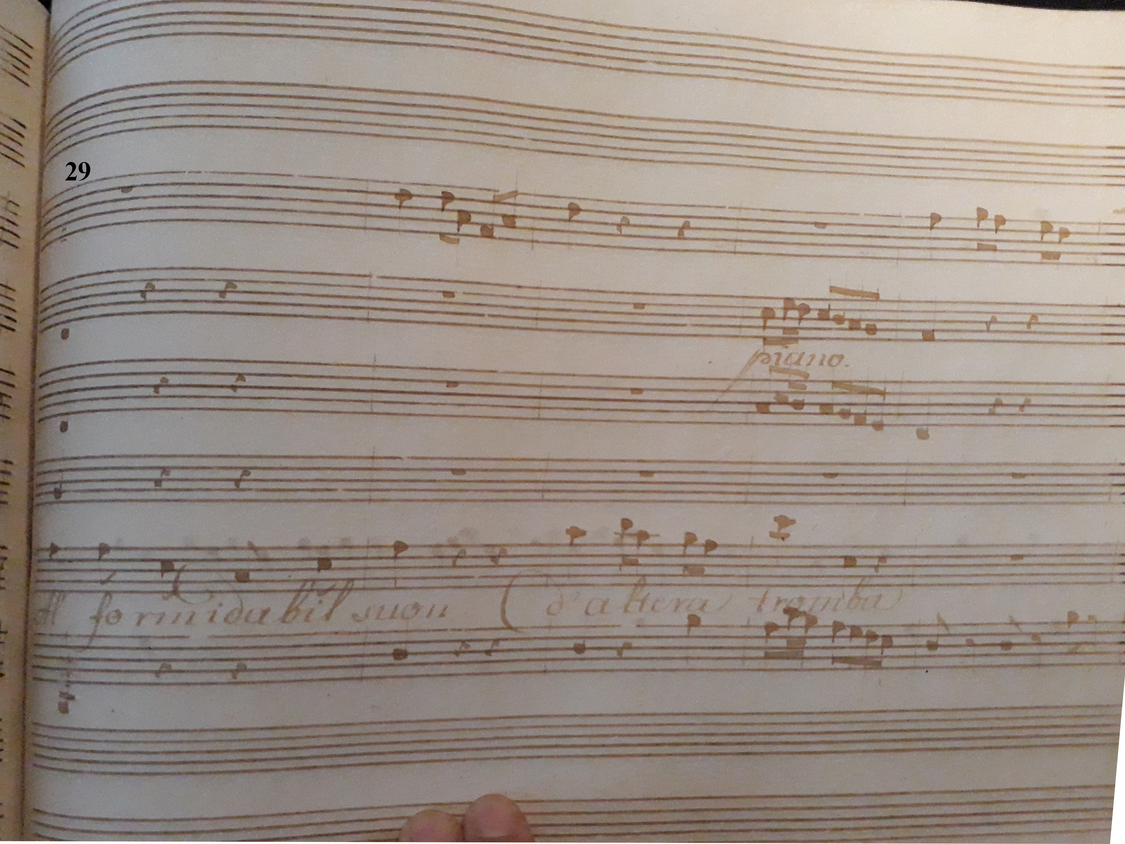

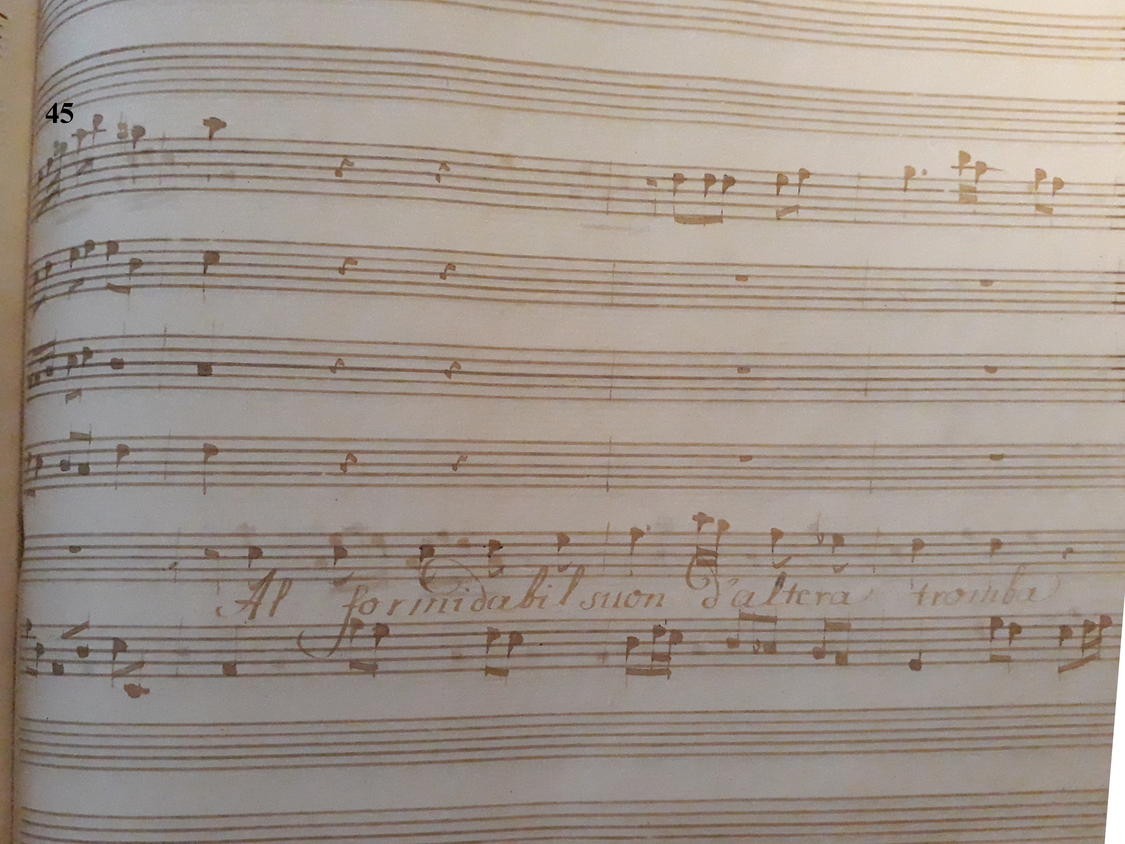

After a discussion between Amor Divino, La Religione, Fama and Onor Divino, this one evokes the fact that the powerful sound of God's love, like the sound of a high trumpet in the hearts of warriors, can awaken generous and strong feelings and thoughts of love in the hearts of heroes.

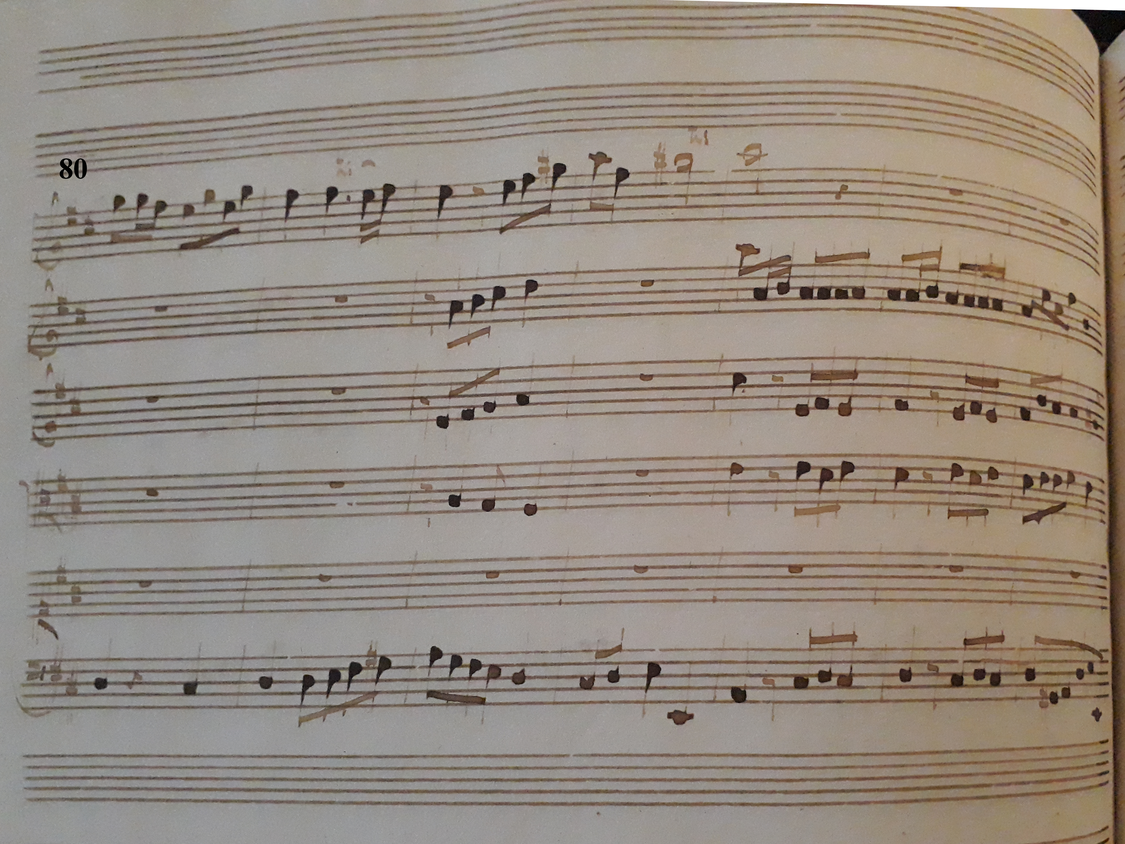

This aria is written for trumpet, strings (violin I and II, violas) and basso continuo(BC). The allegro tempo makes it possible to feel the slight pendulum given by the 3/4.

In the introduction, the trumpet seems to have both a melodic and a rhythmic role, while the strings seem more confined to a pure rhythmic role (repetition of the same notes).

The bright, high sound of the trumpet is mentioned in the text, which in my opinion explains the writing in the high register and the rapid vocalizations that Caldara composed for the instrument. The trumpet introduces the melody which will then be sung by Onor Divino.

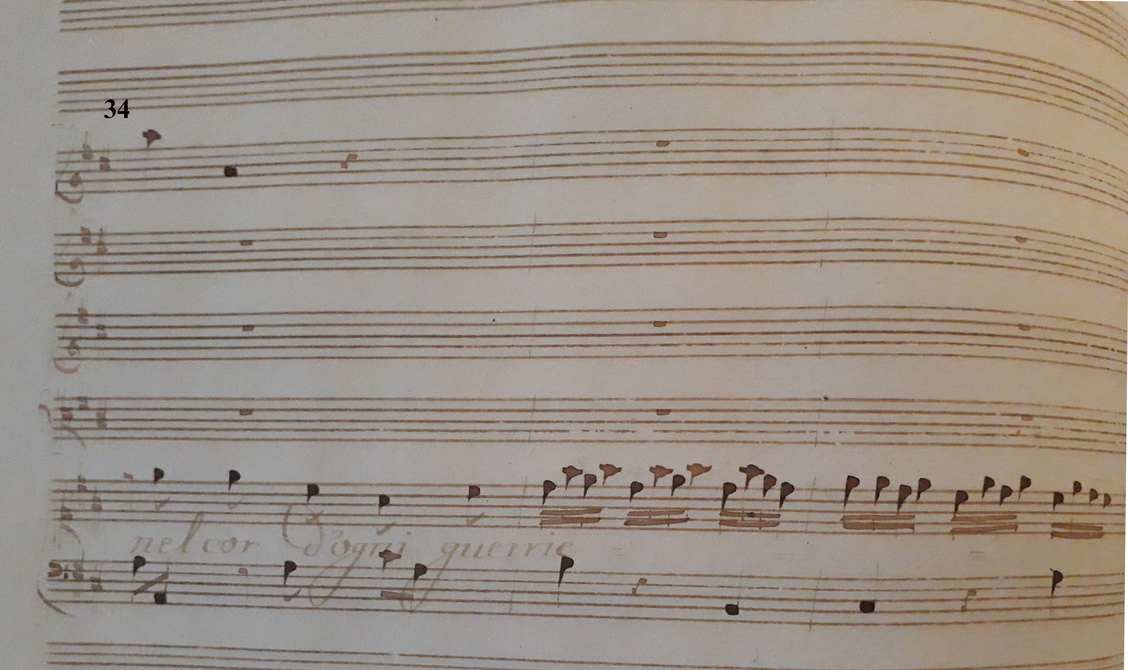

When the voice enters at bar 29, it exposes the text almost alone, with motifs taken up identically to the trumpet.

A long vocalise on the word "guerriero" (warrior) then repeats the same melody as the trumpet in the introduction.

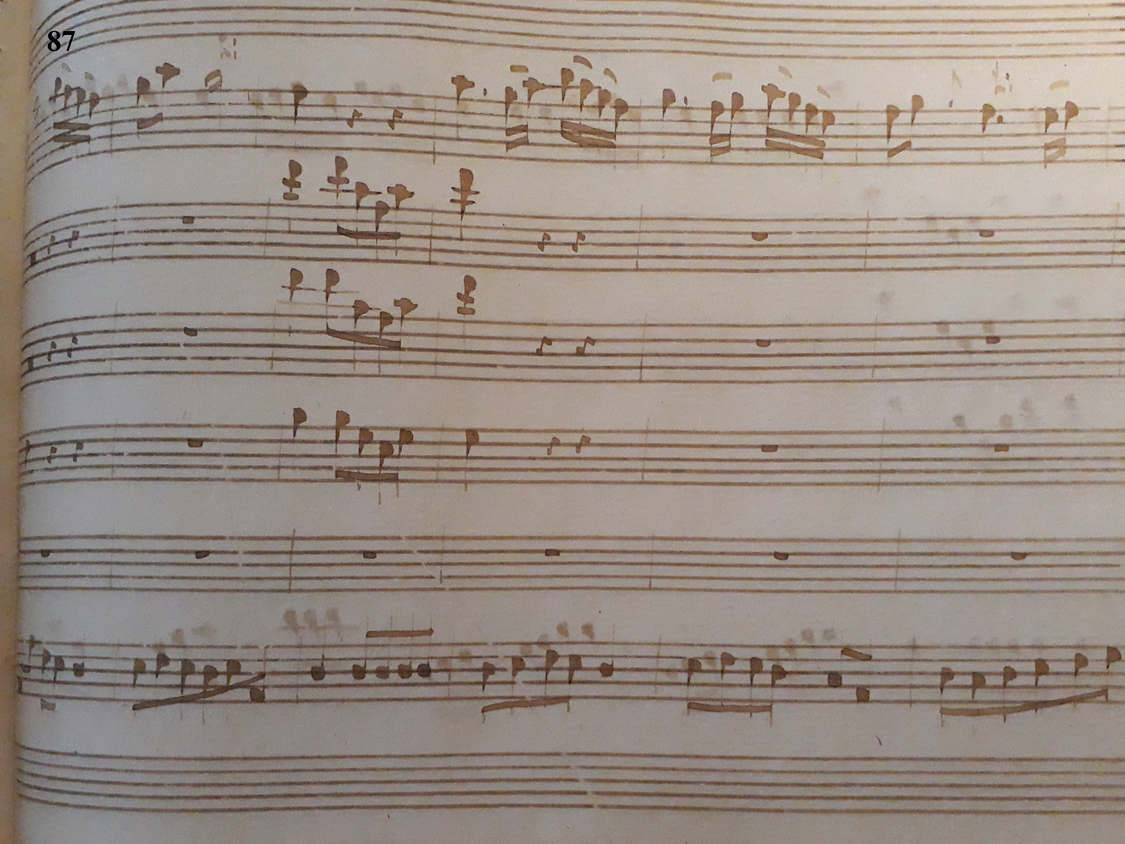

The second exposition of the text that begins bar 46 shows us the trumpet taking up more space in its dialogue with the voice. At the beginning of the new vocalization on "guerriero" bar 50, the trumpet and the voice answer each other before joining the third as if they were the same instrument, the same voice.

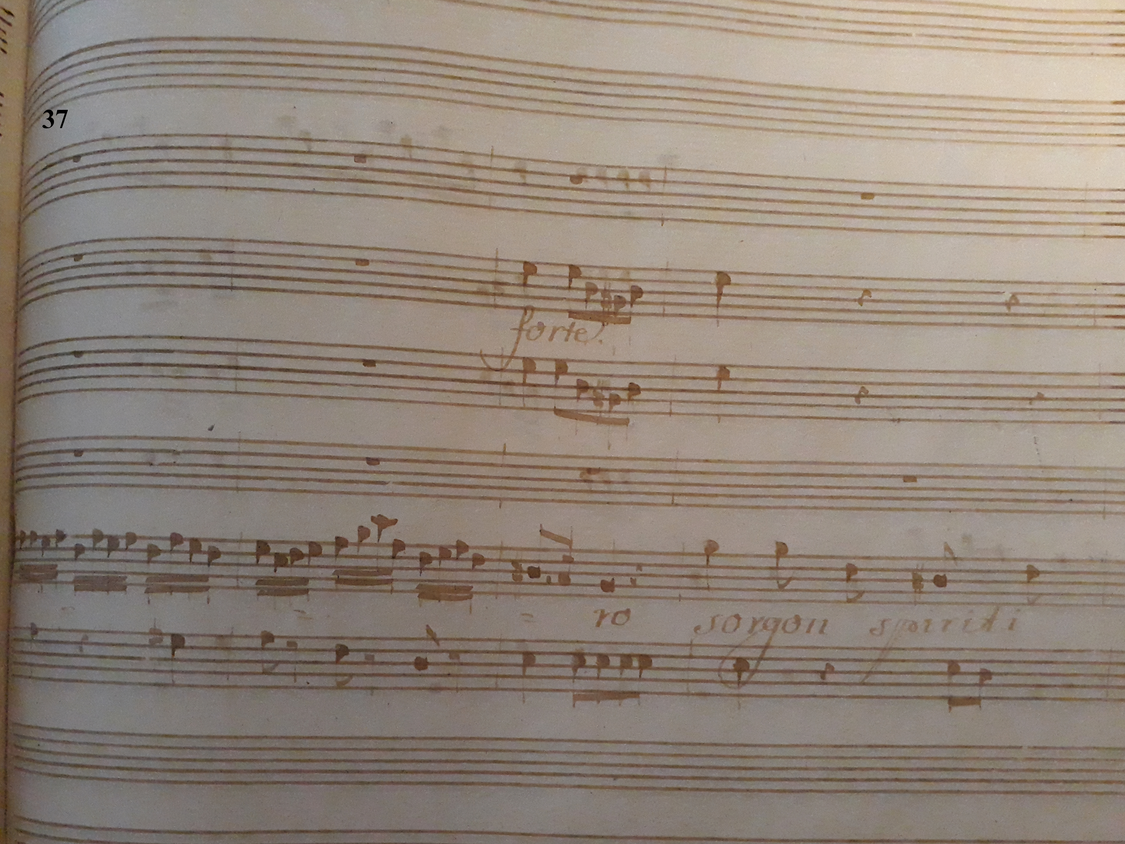

At 59, the rest of the text ("sorgon spiriti forti e generosi") exposes for the first time a vocalise on the word "forti" (strong) where the voice is accompanied only by the BC until the long holding of the A. At this point, the strings and trumpet are very rhythmic with marked rhythms up to the cadence of 71. This part of the text is then repeated one last time only with the BC up to the cadence of 75.

The instruments then repeat the instrumental ritornello from the beginning to the B part at bar 103.

The B part is very short compared to part A: Onor Divino exposes the text twice in a row and lasts a total of 21 bars (up to 124). The trumpet is absent from this part, and the voice is accompanied mainly by the basso continuo.

For me, in this aria, the voice and the trumpet are one in this almost instrumental writing of Onor Divino's melody.

The liveliness of the aria captures the warlike spirit given to the instrument to express this victorious joy.

The trumpet as an obligatory instrument gives a lively rhythm through repeated arpeggios and long vocalizations. Mentioned in the text, the trumpet in this bright tonality is a sort of mise en abyme of the words sung by Onor Divino and wakes up the hearts of the listeners.

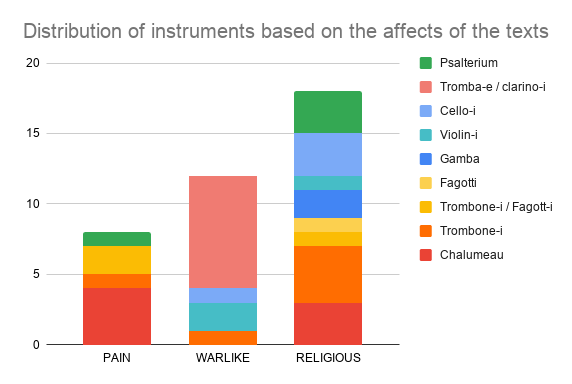

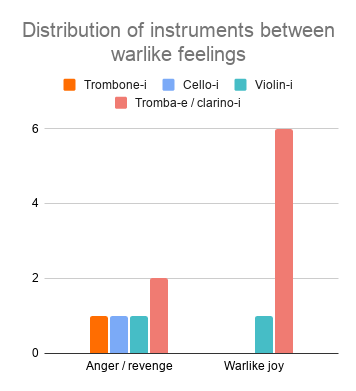

As you can see in the previous table and the graph opposite, 5 out of 12 arias have texts rather related to anger and revenge, and the 7 others are rather borrowed from a warlike joy.

-

8 of these arias have the trumpet (or its high register, the clarino) as their obbligato instrument.

-

3 arias with strings (2 for the expression of anger and revenge and 1 for warlike joy)

-

the last aria is on the trombone and ranks among anger and revenge.

Among these 12 arias, half are for alto voice, 3 for soprano voice, 2 for tenor and there is also one soprano-bass duet.

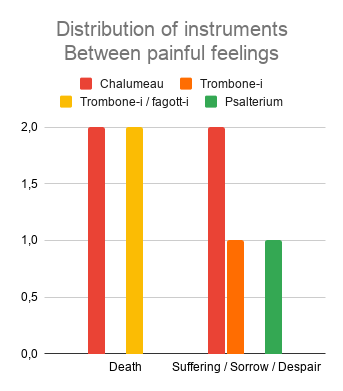

As can be seen in the previous table and on the graph opposite to it, 4 of these 8 arias express suffering, and 4 evoke death.

What can be observed is that the instruments most represented in the accompaniment of these affects are the winds, with 7 pieces in total:

-

4 with chalumeau: the largest number of arias (half): 2 for the expression of death, and 2 for suffering.

-

2 with trombone and bassoon: expression of death.

-

1 with trombone solo: expression of pain.

The psalterium (1) also participates in the expression of suffering but to a lesser degree.

What can also be noticed in the table is that the texts evoking death are sung by soprano voices. Two of the three characters are women (Maria Maddalena and Raab), and the third is a man (Naboth). This does not mean that the texts about death are particularly intended for sopranos, it just shows in these 21 oratorios that Caldara decided to give these roles to sopranos.

For the arias expressing suffering, there are 2 for alto and 2 for soprano. Here again, we can simply notice that Caldara gave these roles to high-pitched voices.

2.2.1 Brief introduction about affects

When we come to talk about affects in music, it seems we need to talk about rhetoric as well. The expression of affects in music has always been linked to the art of rhetoric which was applied in all forms of art (painting, sculpture, music, architecture, etc.) from the Renaissance to the 19th century in the Western world.1

This art of oratory, which was the basis of the education of free young men in Ancient Rome and Greece, became from the Middle Ages onwards one of the pillars of the Trivium (grammar, rhetoric, dialectics), and finally became the main basis of the education of young people from educated and well-to-do families in the Renaissance until the 19th century.

The rediscovery and translation into vernacular languages of the works of Greek (Aristotle, Hermogenes) and Roman (Cicero, Quintilian) authors in the 16th century contributed greatly to the spread of the ideas and tools of rhetoric throughout society.

The main aim of the rhetorical process is to persuade the listener by using a particular way of speaking. In doing so, the orator leads the listener to have the same opinion as he does.2 The persuasive technique is a way of moving the emotions of the listener, but also a way of entertaining his intellect.3 For Judy Tarling, in The Weapons of Rhetoric, the use of rhetoric in music does not even need to be proven any more, and is the true basis of all musical discourse of the Western world between 1500 and 1800.4 What can indeed be striking when one is interested in music and rhetoric is to see that the same words are used to evoke the form of the musical or non musical discourse: tessitura, gestures, phrasing, rests, etc. For Georges J. Buelow, we can see the rhetoric “as the basis of aesthetic and theoretical concepts in earlier music”.5 He even considers everything that we define as typically baroque as “tied, directly or indirectly, to rhetorical concepts”.6

Composers-performers of the 17th and 18th century were perfectly aware about those rhetorical tools and many of them wrote in their treatises about this subject. For Judy Tarling, the audience of the 17th and 18th centuries was well informed about the form of the discourse and was very active in the way of listening to the music. The listeners were expecting to be moved and touched, but also they wanted to be intellectually nourished by feeling that what they were listening to echoed their knowledge and thoughts.7 On his/her side, the composer knew whom he was composing for, and tried to do his best to please the audience and suit its expectations.8

I am not going to retrace here what rhetoric is, nor what all the tools developed and theorised by ancient and modern thinkers are, because it is not the main subject of my research. I would simply like to highlight the fact that the expression of affects seems to be intrinsically linked to this art of oratory, and that it is even its goal. It appears that the same applies to music, where rhetoric has finally taken its place with the ultimate aim of moving the passions of the soul into the hearts and bodies of the listeners.9

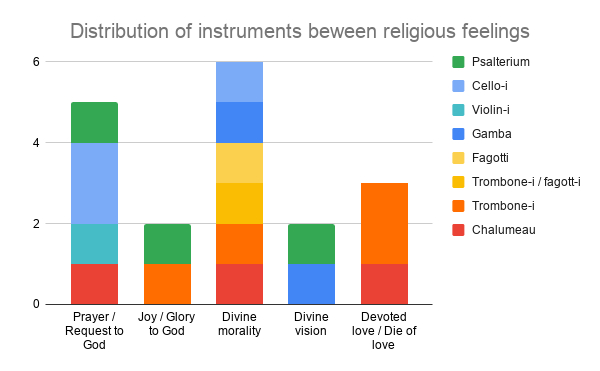

In order to carry out my research on the question of affects in the arias with obbligato instrument of Caldara's oratorios composed in Vienna, I started from the texts of the arias. After translating them from Italian to English, and placing them in the context of the libretto, I classified them into three different categories of affects : pain, warlike feelings and religious feelings. By affects I mean feelings, emotions or moods.10 In fact, it refers to all states of mind and physical reactions that are not considered intellectual.11 For Judy Tarling, an affect is the physical consequence of an emotion that passes through us; it affects us physically.12 These affects can therefore be: sadness, joy, fear, hatred, anger, jealousy etc. And their physical consequences can be, among many others, goose bumps, chills, tears that rise to the eyes, an accelerated heart rate.

I have divided the feelings and emotions that I have isolated from these texts into 3 main categories (pain, warlike feelings and religious feelings). After that, I focused on the tonalities and instruments that were related to these texts. So I was able to arrive at this graph showing the distribution of the instruments within these three categories. I would like to make it clear that I did not start from the instruments and the idea I had of them in order to classify them into different affects. As many writings from the Baroque period say, I started with the affects that were reflected in the texts13 before I looked at the instrument that accompanied them. In fact, Western music was still predominantly vocal in the 17th and 18th centuries, so it was totally linked to words. Composers were therefore "influenced by the rhetorical arrangement of the texts they wanted to set to music" and every musical idea must express an affective element inherent in or required by the text.14

I am aware of the so-called doctrine of affects (Affektenlehre), the name and content of which was created at the beginning of the 20th century by German musicologists to refer to the evocation of affects in music that was dominant during the 17th and 18th centuries.15 This doctrine presents a list of basic affects (admiration, love, hatred, desire, joy, and sadness, often supplemented by anger and jealousy) from which I have both drawn inspiration and departed when studying the texts of my arias. Indeed, I wanted to refine the emotional atmosphere present in the texts by creating categories that corresponded more to the context of the libretti. Since the oratorios are composed for a sacred context during the Lenten period, it seemed natural to me that a category should be entirely related to divine and devout feelings.

2.2.2 My categories of affects

These three categories are divided as follows:

|

PAIN :

|

WARLIKE FEELINGS :

|

RELIGIOUS FEELINGS :

|

In order to give an idea of how Caldara composed for the obbligato instruments and the voice, I propose a brief analysis of one aria for each of the affects. Indeed, having 38 arias at my disposal, I have chosen to highlight a fews, which will not cover the whole range of the arias I examined, but will display the richness of the composition and the diversity of the emotions evoked. I have therefore chosen to analyse arias with different instruments, coming from different oratorios, with the idea of showing the variety of treatments of the affects through the use of obbligato instruments. However, this choice remains very personal and is the result of the knowledge and pleasure I had in working with these arias.

I would also like to point out that the classification of the texts into affects was not simple and often several possibilities were open to my interpretation. By placing the texts back in the context of the libretto of the oratorio, I hope to have succeeded in staying as close as possible to the affects present in the text by choosing to highlight one of them. Indeed, it was recommended to 18th-century composers not to express more than one affect at a time in a piece, in order to maintain a certain "rational unity" which would then be imposed on all the elements of the piece.16 That is how I arrived at these three main categories, themselves divided into several feelings or emotions.

A simple observation of the tables and graphs above may allow us to notice the following:

-

Domination of ternary time signatures (7 arias out of 12): 5 arias in 3/4 and 2 in 3/8

-

The tempi are rather fast: 8 allegro (including all the arias (7) of the warlike joy category), 2 risoluto, 1 andante, and 1 presto in the B part of a slow aria (largo).

-

The tonalities of the A parts are all major: 8 arias in C Major, 2 in F Major, 1 in B flat Major and 1 in D Major.

-

The tonalities of the B parts are mostly minor (10 out of 12): dominance of A Minor (4) and E Minor (4) tonalities.

-

7 arias are joined by strings

-

2 arias with trumpet are joined by timpani (Assalone and Consigliere)

I would like to focus on certain recurring tonalities: C Major, A Minor and E Minor.

For Charpentier, the tonality of C Major gives a "gay and warlike" feeling and for Rousseau, it "marks greatness". For his part, Mattheson finds that it is a tonality which has a rather rough character, but which can nevertheless be used for festivities and for the expression of joy.

In the Caldara arias before us, I find that the mention of "warrior" corresponds particularly to the affects I have sought to emphasize in these texts, and which seem to be enhanced by the choice of these tonalities, which are also linked to the solo instrument, the trumpet.

For A Minor, Charpentier writes that he is "tender and plaintive", whereas Masson sees him as favourable to prayer or fervour. Rousseau says it is serious, and Mattheson sees it as an invitation to sleep or as leaning towards flattery.

In the case of our Caldara arias, one can notice in the texts a sort of request in the central parts, as if the character was waiting or asking for God's help to carry out his work.

For our authors, the tonality of E Minor is rather plaintive, "for the tender" or even amorous and pensive.

Looking at these arias, I would say that there is not much connection with the affects described by Charpentier, Rousseau and Mattheson in this case. Rather, the affects of these arias are either victorious, joyful or full of destructive anger.

For Charpentier, the tonality of C Major gives a "gay and warlike" feeling and for Rousseau, it "marks greatness". For his part, Mattheson finds that it is a tonality which has a rather rough character, but which can nevertheless be used for festivities and for the expression of joy.

This is not really the case for arias in this category, which shows that, indeed, these links between tonalities and affects as described in these works, do not always allow us to get it right in terms of the expression of affects. And that these could be expressed in different ways than through tonality.

D Minor also seems to meet with the unanimous approval of the four authors; they find him "serious and devout", for being grave, but also devoted and pious.

This tonality is found in all the sections of this category, except in the expression of joy. the pious and devout character is particularly appropriate, in my opinion, to the arias of the devoted love section, where each of the 3 arias is in D Minor at one point.

For A Minor, Charpentier writes that he is "tender and plaintive", whereas Masson sees him as favourable to prayer or fervour. Rousseau says it is serious, and Mattheson sees it as an invitation to sleep or as leaning towards flattery.

Opinions are quite dissimilar on this tonality, which is quite consistent with the diversity of arias having this tonality in this vast category.

About G Minor, Rousseau says it can be used "for the sad", Charpentier describes it as "serious and magnificent", while Masson paints it as "full of softness and tenderness". For Mattheson, it is "one of the most beautiful tones there is (...), full of immense grace and gentleness (...), which is appropriate for short and moderate laments". The three arias in this key do indeed show a certain sadness in the text, even a kind of lament.

Throughout my research, I kept in mind several guiding questions:

-

Would I find recurrences of instrument use related to certain affects?

-

Apart from the attribution of instruments to certain affects, could I uncover different ways of using these instruments to enhance the text?

-

Were certain instruments particularly appropriate for a certain type of character in the oratorios?

In the analysed examples shown, my main concern is to present a way of using the instrument rather than to present a generality of how instruments are used in their respective category of affects. Indeed, I consider that I cannot make any categorical assertion about the use of obbligato instruments by Antonio Caldara in his oratorios, because to do so, I would have to be able to have studied the oratorios of other composers, Italian or Germanic, composed in the same period of time and in the same place, and to be able to compare them with each other with the aim of finding recurrences in these obbligato instruments or particularities specific to certain composers.

I can therefore only observe and note what has become apparent through the study of these 38 arias with obbligato instrument, without trying to make it a universal and immutable truth.

Recurrence between the attribution of certain instruments to certain affects

I have been able to observe the recurrence of attribution of certain instruments to certain affects thanks to the graphs seen above.

-

The use of the trumpet in warlike arias, whether vengeful or of victorious joy. The eight arias with trumpet in all of Antonio Caldara's oratorios composed in Vienna belong to this warlike category.

-

The recurrence of wind instruments in the category of sorrow (seven out of eight arias), and in particular the use of the chalumeau (four out of eight), with similarities in tempi and tonality (G minor and C minor). The use of minor tonalities (G, D and C minor) in the six pieces out of seven with chalumeau in the oratorios, their slow tempi and their texts definitively classify them in a languorous and plaintive expression of the texts it supports.

-

The combination of the trombone and bassoon in the category of pain (in the sub-category of the expression of death) also made me lean towards a kind of evidence of the use of these instruments together to express this type of affect, but the appearance of an aria (which I classified as a religious feeling, in the sub-category of divine morality) with a playful and lively character with this same combination immediately made me give up asserting the use of trombone and bassoon together as directly related to Caldara's expression of death. Even if the use of the trombone, and in particular of a trombones’ chorus, was associated with the expression of subterranean worlds and death in the 17th century, the appearance of joyful arias with trombone (Giovanni, in La Passione di Gesù Cristo) or that of Jojada (in Gioaz, Re di Giuda) led me to also consider another use of the trombone, more related to joy. However, of the nine arias with trombone, five are still associated with death, whether it be on the side of sorrow or divine love for which the character is prepared to die.

-

The prevalence of string instruments to express a prayer is also striking (four out of five arias), although it is divided among three instruments: violin, cello and salterio.

-

The sub-category of divine morality is also more represented by wind instruments than by strings (four out of six arias).

-

The sub-category of devout love is represented entirely by the winds, notably the chalumeau (one aria) and the trombone (two arias). These arias are as plaintive and languorous as those of sorrow, because of the words of the texts: accept pain and suffering to please the Lord or die and languish to endure, out of love, the same fate as Christ.

-

The salterio, used four times as an obbligato instrument, is mainly present in the category of religious feelings, whether for the expression of a prayer, thanksgiving to God or the reception of a divine vision.

To sum up, I will say that there are three obvious observations:

1. The trumpet associated with warlike feelings

2. The chalumeau and the trombone associated with feelings of suffering or death, whether for love of God or just through the life experiences of these characters

3. The salterio is mainly associated with the expression of the divine

3) The imitation of words sung or the illustration of the purpose of the text by a specific melody and a rhythmic role of the instrument. In the three arias that follow, one can hear the "formidable sound of the trumpet" referred to in Onor Divino's aria, then the tumultuous river and its waves rendered by the bassoon in "Cosi à fiume" and finally Athalia's anger and fear expressed by the excitement of the violin.

4) The use of a kind of choir of several instruments that will create the harmonic atmosphere of the aria by producing a kind of sound carpet. In the example, there are two trombones and two bassoons supporting Maria Maddalena's grief. They do not sing the melody or imitate what Maria Maddalena sings.

Instruments related to particular characters

I did not actually find any recurrence between certain characters and obbligato instrument in these 38 arias, except in the case of one instrument, the salterio, for which the link between the choice of instrument and the associated characters is not in doubt for me.

The salterio is used four times, for four different characters. The first appearance of the instrument in Caldara's oratorios takes place in 1725 in the oratorio Le Profezie evangeliche di Isaia, then the following year in Gioseffo che intepreta i sogni, in David umiliato composed in 1731 and finally in Sedecia composed in 1732. The characters who sing these arias are Eliacim, Gioseffo, David and Geremia.

For me, these four characters are linked in their strong relationship with God:

-

A relationship of trust and love for Eliacim, who seeks to follow the prophet Isaiah.

-

For Gioseffo, it is God who allows him to interpret dreams and win the trust of Pharaoh.

-

David, an aria of praise to God for the help he has given him

-

A report on the transmission of the divine word through Geremia, who is a prophet.

It was King David singing his aria of praise to God who evoked to me the representations of King David in medieval illuminations often found in psalters: King David with his harp, striking bells, playing the fiddle, or represented with a psalterion (salterio).

In this table you can find the Italian texts and the English translation of the texts that I have classified as belonging to the category of the affects of suffering and death.

In this table you can find the Italian texts and the English translation of the texts that I have classified as belonging to the category of the affects of anger, revenge and warlike joy.

In this table you can find the Italian texts and the English translation of the texts that I have classified as belonging to the category of the affects of prayer, joy, devoted love, divie morality and divine vision.

2) The role of transmitting a prayer to God or the divine word to humans. The instruments used are mainly strings. The lightness of their playing and the airiness of the sound create a real atmosphere of concentration or devotion. In the two arias that follow, one can hear the salterio and the viola da gamba, the first for an air of prayer, the second for the transmission of a divine vision.

King David is considered to be the author of the psalms in the biblical tradition, and the mention of "Psalm of David" is found in the Bible. In medieval illuminations he is often found tuning the instrument, as if he was tuning men (so to say the earth), to God (the heaven and the universe, as it were). Represented mostly with a harp in these medieval manuscripts, it made me think of the sound of the salterio, airy, light and harmonious. For me, the fact that Antonio Caldara gave David this aria of praise accompanied by the salterio is clearly linked to the representation of David singing and receiving the psalms, which are mainly used for divine praise. In the aria by Eliacim, a friend of the prophet Isaia, he asks God to help him not to disappoint him, to close his mouth so that no flattery comes out of it. Gioseffo, for his part, interprets the dreams and reveals them to Pharaoh. Here, too, it is a question of divine presence and the translation of words received in images into human verb. Finally, Geremia is a prophet, and he receives in the aria with salterio, a divine vision that he transmits to the people around him.

In all these arias, there is a direct link to God and the word, whether divine (vision, dreams) or human (prayer, praise). I will never know whether the attribution of these arias to the salterio is purely coincidental, and if so, the resemblance of these characters in their connection to God associated with the salterio would be a pure coincidence. But for me the salterio here is that divine instrument, that biblical instrument used by David, which in the aria of Caldara implies this divine connection between God and these four figures, God and humans in general. The listeners of the Hofmusikkapelle were all Christians, members of an extremely Catholic imperial family, and if not all of them participated in the daily services, it is possible that they went to mass almost every day. So, they knew the psalms, and of course King David. In my opinion, it is clear that the reference to David's harp through the salterio was to be perceived by the listeners of the Hofmusikkapelle.

To access the scores of these arias and musical excerpts, visit this page.

The simple observation of the previous table and graph can already show us several things about the recurring choices made by Caldara to capture the atmosphere of suffering, sorrow and death in these arias:

-

The choice of slow, even very slow tempi (from Largo to Andante)

-

The predominance of minor tonalities and in particular of G Minor which appears in 5 out of 8 pieces.

-

The predominance of this same key (G Minor) for arias with chalumeau (4 out of 4)

-

The combination of G Minor and C Minor in three arias (2 for chalumeau (Gioseffo, Achinoam), 1 for trombone and bassoon (Naboth))

-

The predominance of binarity with 5 out of 8 pieces in C

-

Only two arias start with a major tonality (F Major), and one aria has its B part in major (E flat Major).

I would like to focus on certain recurring tonalities in these arias: G Minor, C Minor, F Major and D Minor.

To refer to these links between tonalities and affects, I based myself on four authors whose works were published during Caldara's lifetime. Three of them are French (Marc Antoine Charpentier, Jean Rousseau and Charles Masson) and the last one is German (Johann Mattheson). Their works were published in 1690, 1691, 1697 and 1713 respectively.17 I assume that these works were circulating in Europe and that Caldara may have heard about them in his youth. If this is not the case, it may mean that the tastes of the time were then quite widespread in Europe since there are many similarities between the affect propositions for each tonality within these four books, and also that composers and theoriticians were basing themselves on models already previously established in earlier times.

About G Minor, Rousseau says it can be used "for the sad", Charpentier describes it as "serious and magnificent", while Masson paints it as "full of softness and tenderness". For Mattheson, it is "one of the most beautiful tones there is [...], full of immense grace and gentleness [...], which is appropriate for short and moderate laments".

I find that the mention "for the sad" particularly suits Caldara's arias expressing suffering and death. It seems also that it is a tonality very well suited for the chalumeau, as if this instrument could further enhance the softness of this tonality to express the deepest despair.

As for C Minor, it is obscure and sad (Charpentier), plaintive (Masson) and lamentable (Rousseau). Mattheson, on the other hand, finds it full of love, and with a good taste for sadness. On the other hand, it is necessary to animate it a little because it is according to him a tone that leads to sleep.

The sadness inherent in the texts that Caldara has set to music in this selection is therefore well served by the choice of tonality. The gravity of the trombone and bassoon together (Naboth) and the plaintive sweetness of the chalumeau (Gioseffo and Achinoam) are carried by this lamenting C Minor.

For F Major, Rousseau tells us that it is appropriate for "devout pieces or church songs", while Masson writes that it is "naturally gay mixed with gravity".

In the two pieces by Caldara that use in this selection, I think we can feel both a certain lightness and a deep gravity. The psalterio in Gioseffo's aria adds to this lightness with its airy sound. And the gravity can be heard on the words "o pur m'inganni", which means: "or do you deceive me?".

D Minor seems to meet with the unanimous approval of the four authors; they find him "serious and devout", for being grave, but also devoted and pious.

The aria of Maria Maddalena (chalumeau) is entirely in this theme of seriousness and devotion, with this notion of her culpability for the death of Christ.

The different ways of using obbligato instruments to enhance the text in Antonio Caldara's oratorios

Rather than the definitive association of an instrument with a particular affect, I think the most interesting thing is to look at the way the obbligato instrument is used by Antonio Caldara to highlight the texts and the affects they contain. I have not noticed any recurrences linked to a particular affect in these ways of using the instruments, but I have isolated four ways of accompanying the voice while carrying the text. I have chosen to illustrate each of these ways with one to three examples from all the sub-categories.

1) The emphasis on the affects by echoing the melody sung. The instrument is often in imitation of the voice, it precedes or follows its musical phrase. It joins the voice on certain words of the text particularly highlighted by a vocalise. The instrument introduces the aria through the melody, which will then be sung by the character. This way of writing music for voice and instrument is in fact nothing exceptional and can be seen in many arias, both sacred and secular, from the end of the 17th and during the 18th century.18 The three examples that follow, taken from various categories of affects, give a good account of the different feelings that run through them and the support of the instrument as echoes of their pain or their joy.

"Soffrirò pene e tormenti per piacere al mio Signor", Santa Ferma, in Santa Ferma (1717)

Sofia Pedro - soprano, Giulia Zannin - chalumeau, Ensemble La Favorita, The Hague, January 2018

"Deh sciogliete, o mesti lumi", in Morte e sepoltura di Cristo (1724)

Naxos recording (2015), Maria Grazia Schiavo (soprano), Fabio Bondi (conductor)

"Reggimi, o tu, che sola", Eliciam, in Le Profezie evangeliche di Isaia (1725)

Elisabeth Seitz - Salterio obligato, Valer Sabadus - countertenor, Michael Dücker - ensemble director Nuovo Aspetto, recording SONY CLASSICAL 2015

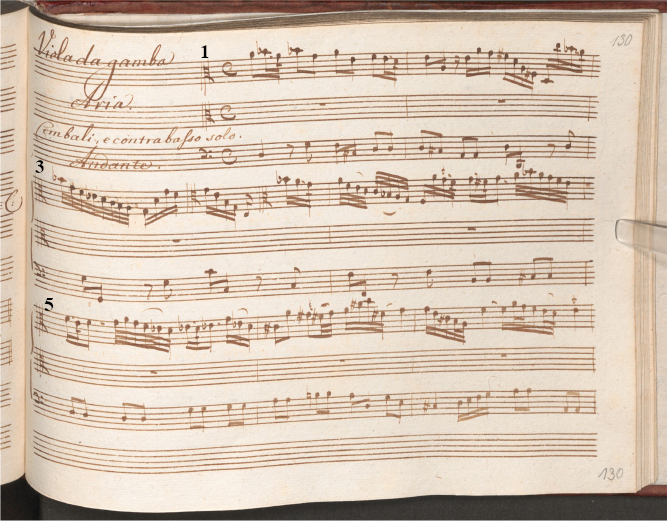

Divine vision - analysed example: Geremia

The aria I am analysing here is the last one sung by Geremia and the last one from the oratorio Sedecia, Re di Giuda (1732). It is one of the two arias that I have classified as divine vision. The second is also sung by Geremia in the same oratorio, but at the end of the first part and accompanied by the salterio.

Geremia is a prophet, he spreads the word of God and advises kings and chiefs who come to see him. In this oratorio, he advises Sedecia, king of Judea, who wants to fight against the Babylonians and their king Nebuchadnezzar. Jerusalem has been destroyed, but in this last vision, Geremia reveals to Sedecia that Jerusalem will be alive again, the Temple will be restored, and God will make it his home again.

The aria is written for viola da gamba, alto voice and basso continuo (BC). It is an andante in C.

The form of the aria is particular: ABABAB, with a different text for each repeat of A or B and some small musical variations written for the last A and B.

The aria begins with an introduction of the viola da gamba accompanied by the BC on the melody which will then be sung in the A part by Geremia.

The musical phrases A and B are quite short and almost entirely syllabic. There is not much space for long vocalises here because the most important is the word of God transmitted by Geremia to Sedecia.

The A1 starts at measure 8. Geremia sings alone, with some melodic repetitions of the viola da gamba during his rests.

At bar 14 the viola da gamba plays a melodic transition between A1 and B1.

B1 starts at bar 16 and ends on the first beat of bar 26. Again, the melody has a rather restricted range and makes the text be heard syllabically. The viola da gamba is more present and accompanies the text throughout this part.

The viola da gamba continues here too with a transition to bar 31. It is not the same melody as before; the viol has both a fast play (thirty-second notes) and also chords and a chromatic ascending line from bars 29 and 30 to the cadenza.

A2 starts bar 31 with the same melody but a different text. The viol responds to the voice in the same way.

At 40, part B2 starts musically similar to B1. The transition from B2 to A3 is quite different from the transition from B1 to A2, it is shorter and less harmonically rich.

The slight melodic differences found in A3, which begins at bar 52, are due to an excess of text and therefore required a faster addition of notes, sometimes with melodic changes suggesting written ornamentation.

The same is true of the last part B3 which begins bar 58 and whose writing is slightly more ornate than that of B1 and B2.

Finally, the prophecy of Geremia stops at bar 66 and gives way to the same instrumental ritornello as at the beginning of the aria.

In my opinion, the viola da gamba here is the translation of the word of God that Geremia receives. Its airy sound, much more than that of the cello for example, is well suited to this atmosphere of transmission of divine word. At once conducive to rapid and virtuosic melodic passages as well as to softer moments of melody, it allows the different atmospheres of the text to be translated.

Here the instrument echoes the text and transmits the divine word by imitating the voice.

Divine morality - analysed example: Jojada

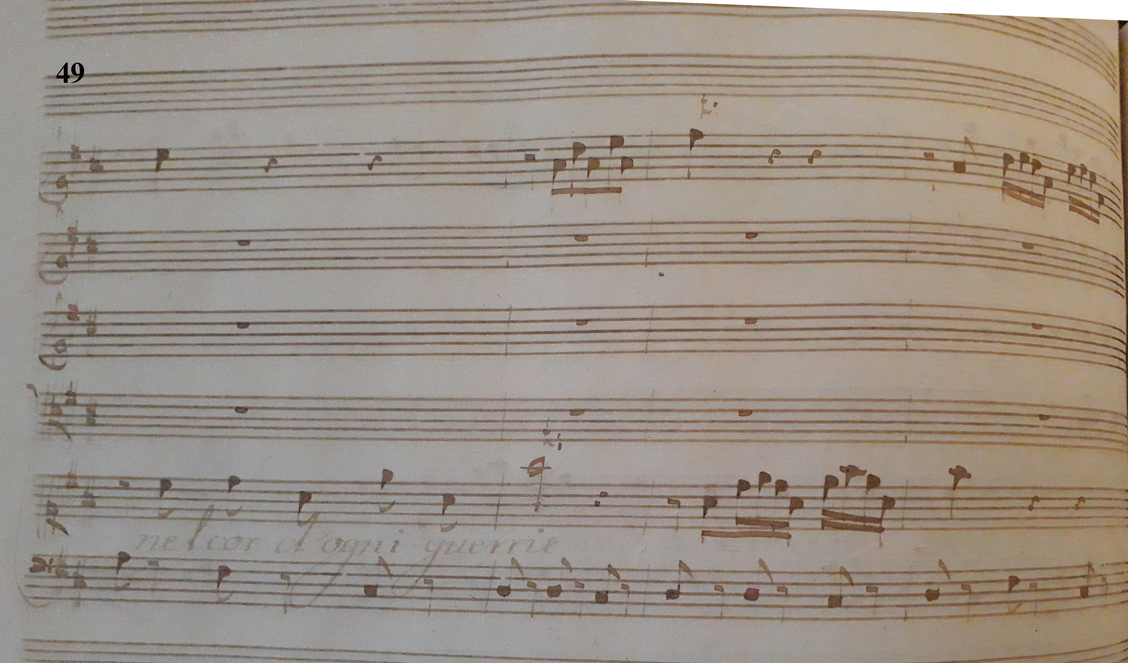

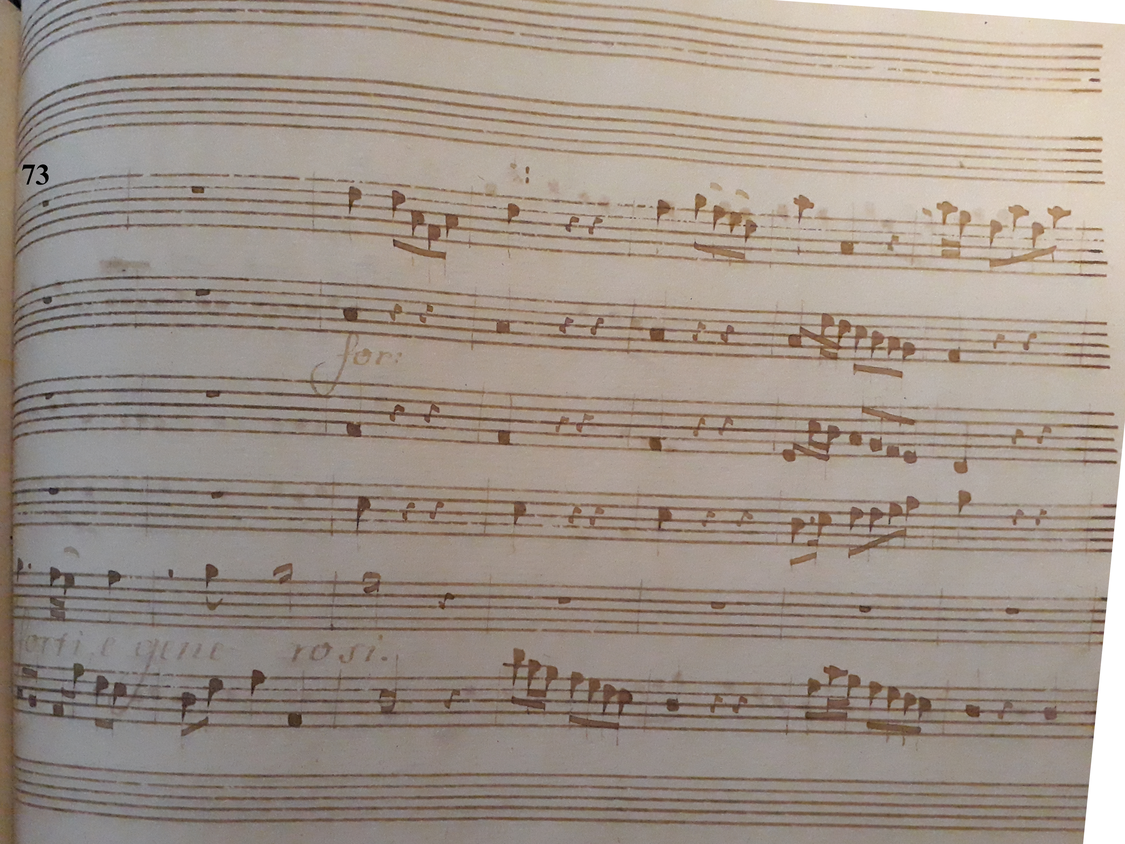

Jojada's aria in Gioaz Rè di Giuda arrives shortly after the beginning of the second part.

It is the second aria sung by this character. The text echoes Jojada's protégé, Gioaz, whom his grandmother Athalia, the present cruel queen, wanted to have killed as a child. Jojada is a priest, and in the preceding story he reveals to Gioaz that he is the legitimate king. In the aria, he then evokes the strength of God, who is slow to anger, but ready to take revenge if necessary, as well as the strength of the torrent that will eventually break the bank and bury the shepherds and flocks there.

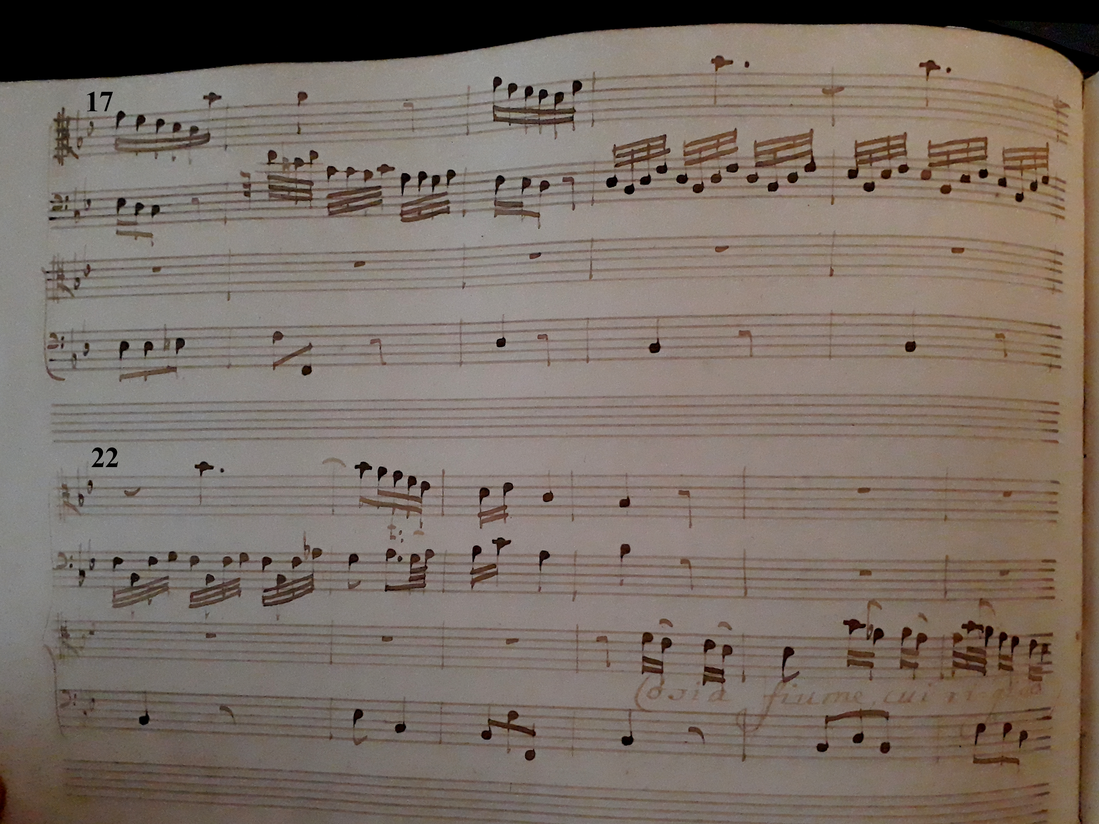

The aria is written for trombone, bassoon, alto voice and basso continuo (BC). It is an andante in 3/8.

The aria is introduced by the trombone with the melody which will then be sung by Jojada. The bassoon seems to have a role here that is at once rhythmic, harmonic and figurative in my opinion. Indeed, rhythmic because of the fast notes it plays and the energy it provokes in the piece. Harmonic because of the numerous arpeggios. Figurative because I have the impression of feeling the tumultuous river it refers to in the text through what it plays. The trombone is more serene with a more melodic role that talks with Jojada. It is as if it carries Jojada's word, a moralizing and metaphorical word that comes from God and which he addresses to Gioaz.

In the first 25 bars, the two instruments play together, the melody on the trombone and this accompaniment in lively and rapid arpeggios on the bassoon.

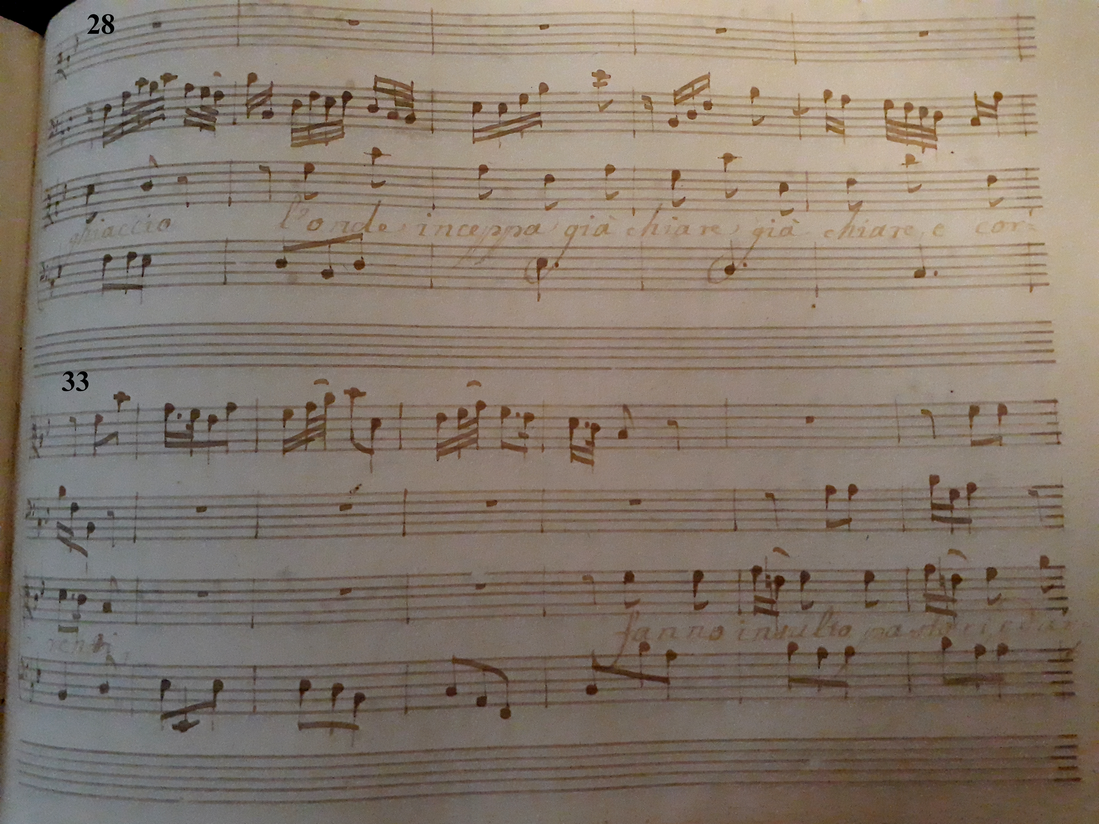

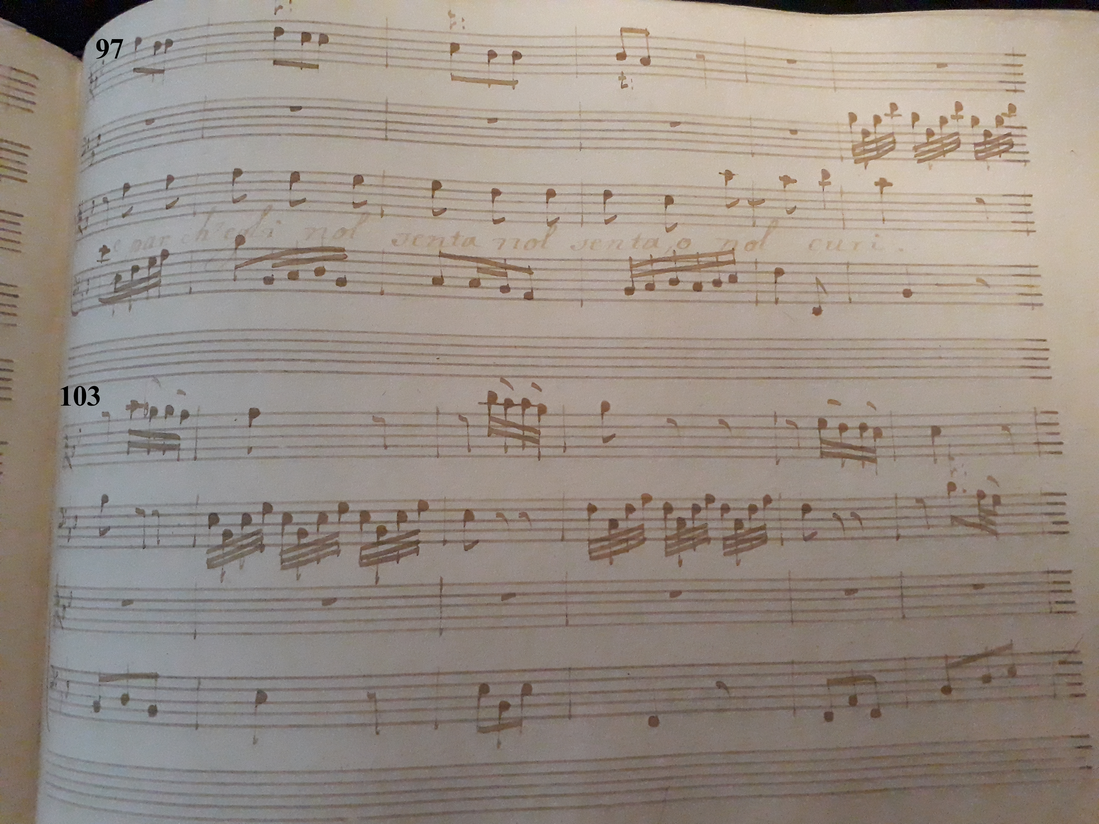

Jojada enters bar 25 and is joined by the bassoon in bar 28, in the same way as in the introduction with the trombone. The trombone intervenes at bar 33, repeating the melodic phrase of the viola. In the second part of the phrase "fanno insulto pastori ed armenti e par ch'egli nol' senta, o nol' curi" (he is insulted by shepherds and flocks, but it seems that he does not hear or pay attention), the voice, bassoon and then trombone enter gradually on the same rhythm from bar 37. This is followed by a vocalise on the word "senta" (hears) bar 42, which gradually shifts the same rapid rhythm from the voice to the instrument until it is heard in each eighth note.

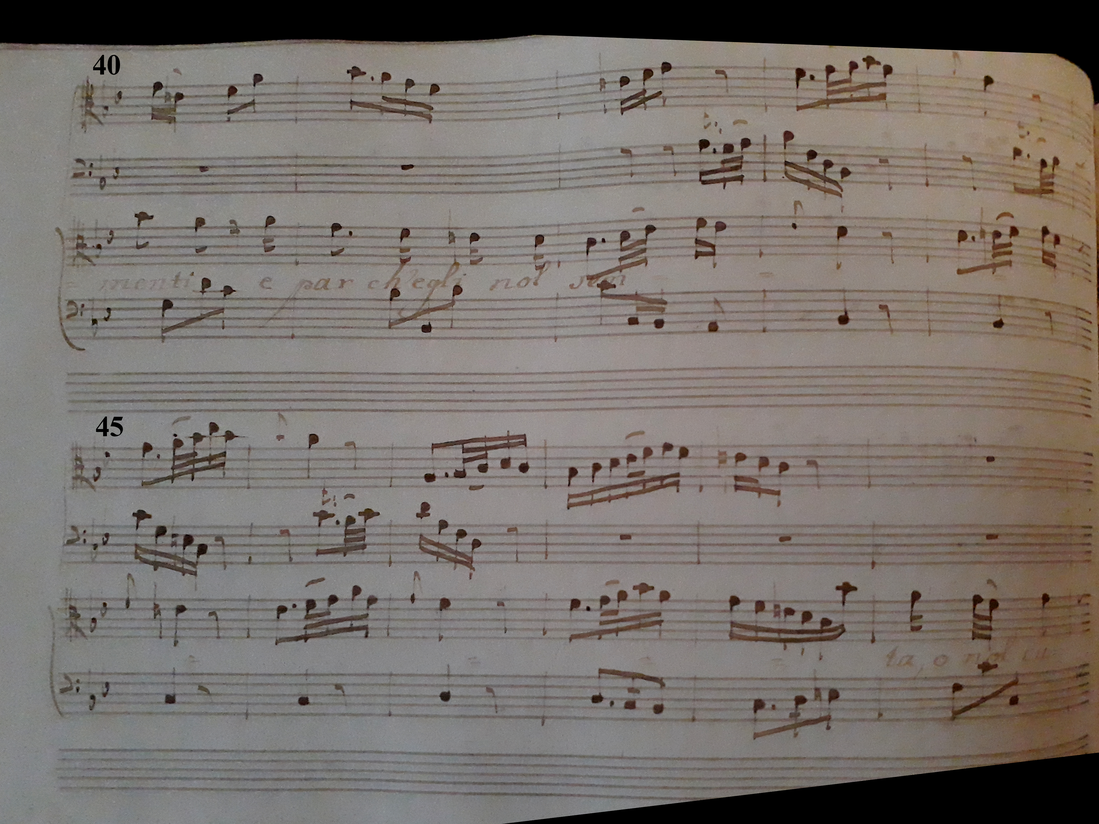

Before the second exposition of the text, an excerpt of the instrumental ritornello from the introduction at bar 51. The voice enters at bar 59 and is joined by the bassoon at bar 63. The bassoon is in very fast arpeggios imitating the moving water running "correnti", and there is a vocalise on this word at bar 67 where the descending motives sung by Jojada are repeated three times in a row on the bassoon.

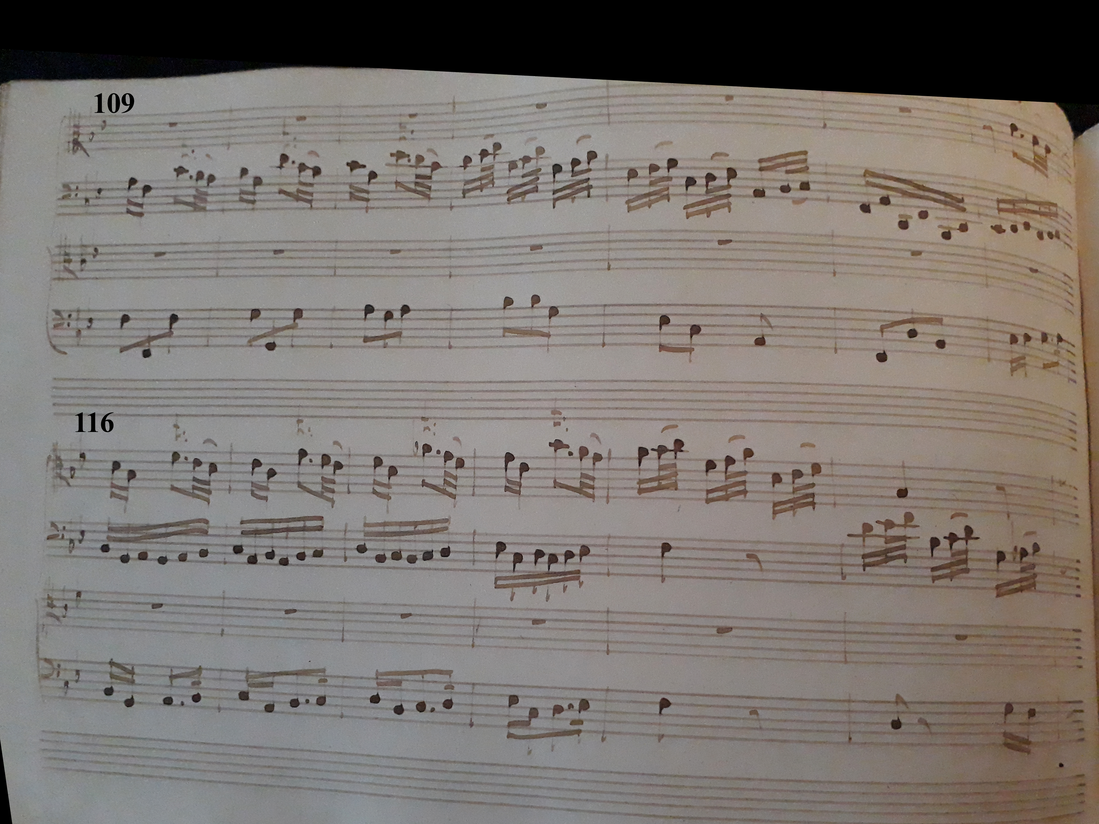

Then the voice continues without the bassoon until the entrance of the trombone at bar 76 which initiates the rhythm of the melody and continues with the imitation of the voice on the vocalization of the word "senta" from bar 79 to 83.

Jojada then repeats the second part of the phrase twice until the final cadenza in bar 102. The trombone and bassoon are then found in their respective roles of melody and rhythmic arpeggios until bar 108. They then continue with a long ascending phrase first on bassoon and then on trombone to the central part, bar 125.

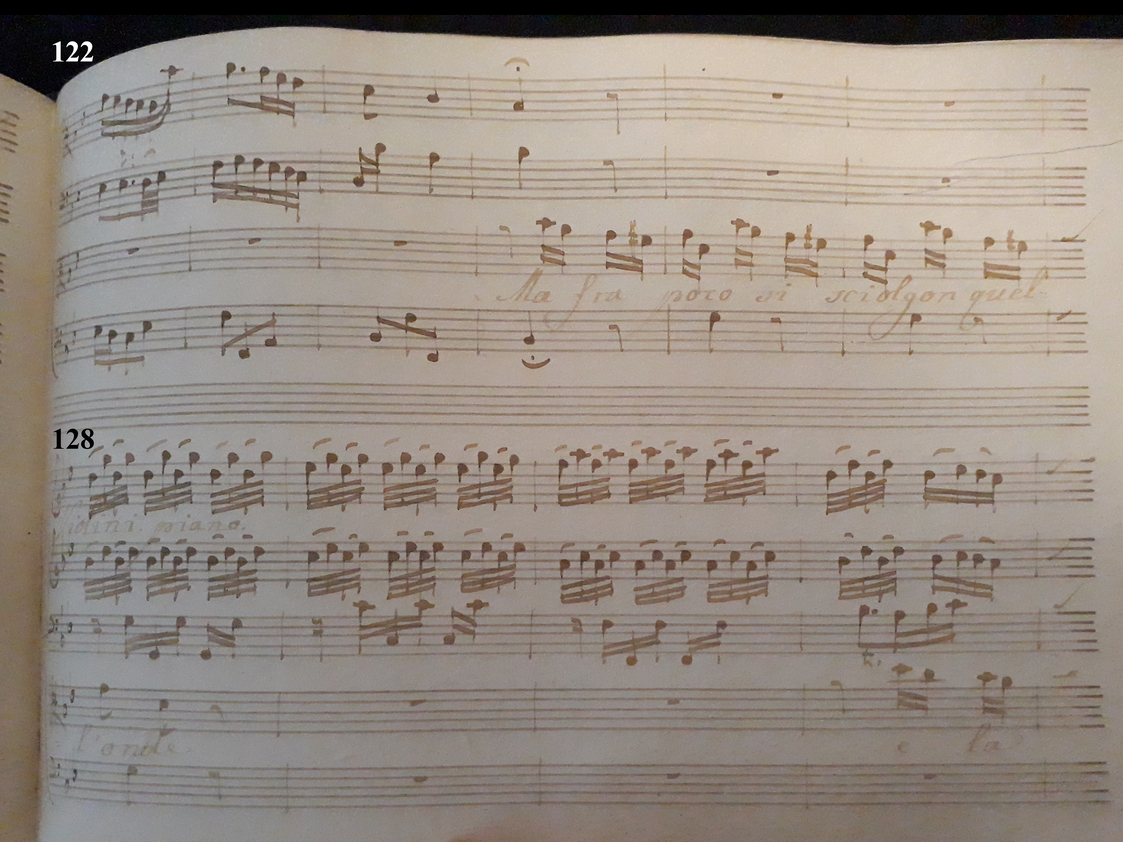

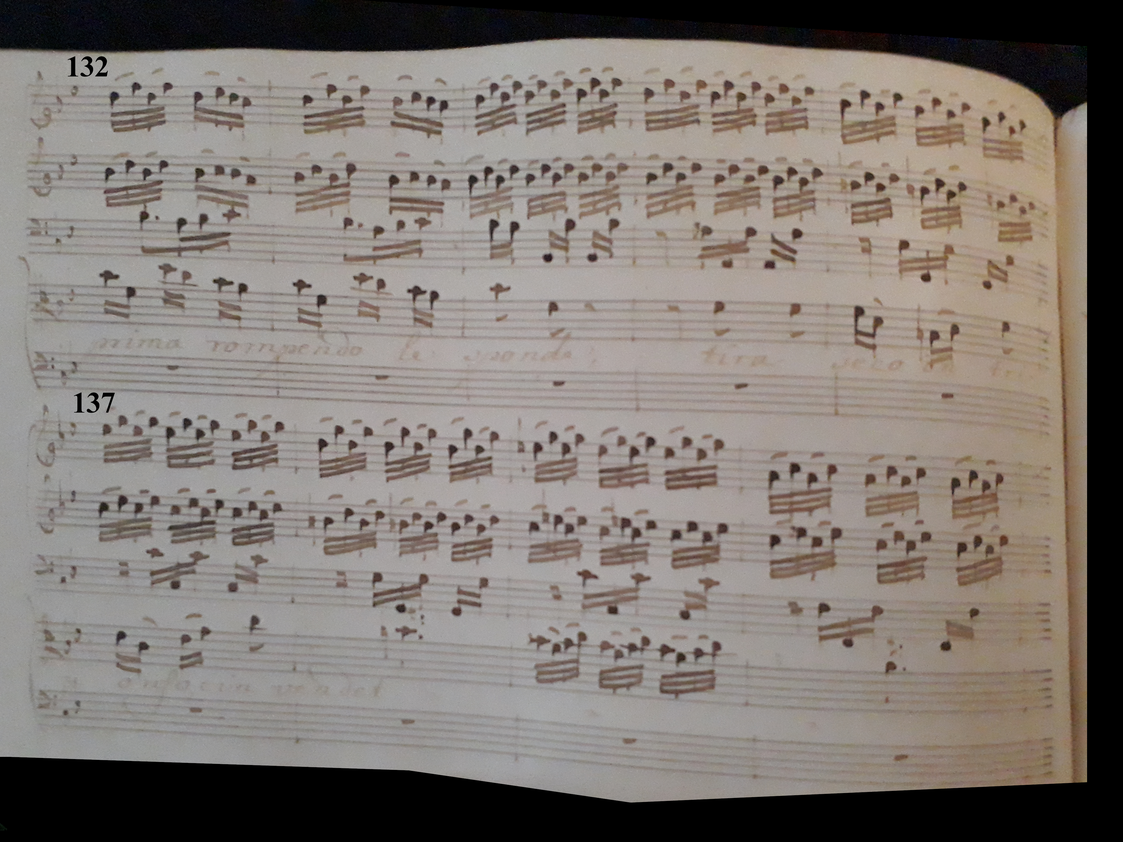

The B part is written for violin I and II, cello, voice and BC. The first part of the text is shown alone with only the basso continuo. Then the strings enter and the rest of the text is accompanied by this excited and furious choir of strings. At 138, there is a vocalise on the word "vendetta" (revenge), the voice sings the same thirty-second notes as the strings. At 149, the voice repeats alone with the BC the last part of the text "i pastori, le gregi, ei tuguri, ei tuguri" (the shepherds, the herds and hovels) on the same melody as the beginning of the central part.

In this aria, which I have classified as part of divine morality, one can see two distinct and complementary roles for the trombone and bassoon. The trombone, much calmer than the bassoon, seems to carry the melody and thus the text. Whereas the bassoon, much more rhythmic, seems to represent the text: the river and its waves in constant motion. One brings the moralizing, or metaphorical word of what is going to happen, the other perfectly illustrates the strong destructive force already on the way under deceptive appearances of calm. The trombone, with its warm sound and the calm temperament it exudes, seems to fit in perfectly with the serenity of Jojada addressing Gioaz.

The instruments are thus linked to the affects of the text by two different means, one carrying the words in a quiet and relaxed manner, the other depicting the moving elements of the text.

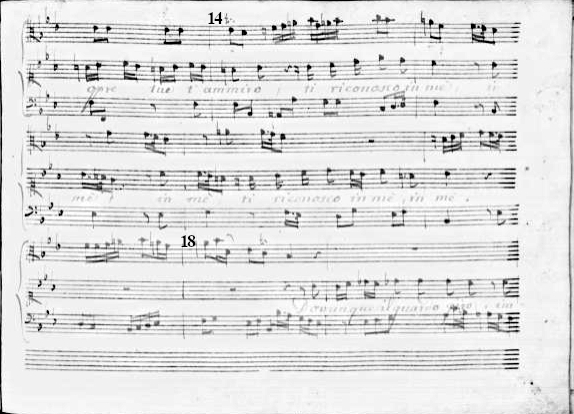

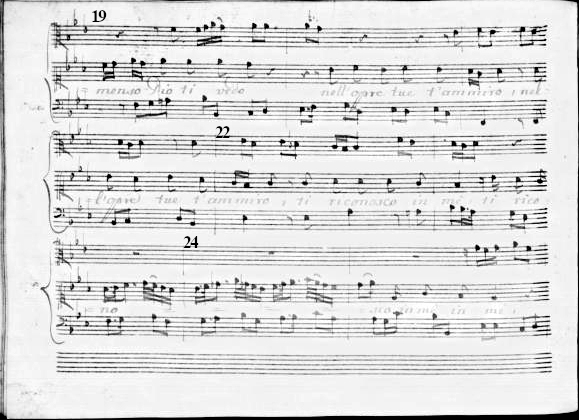

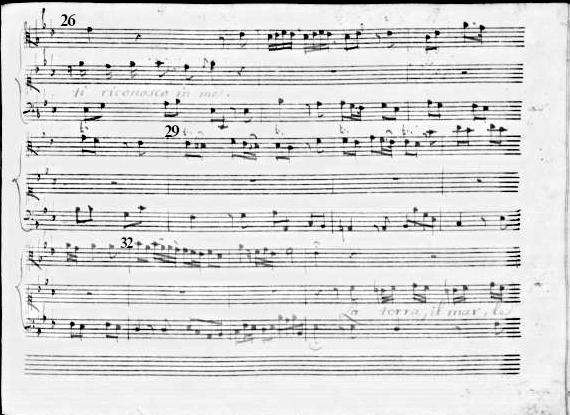

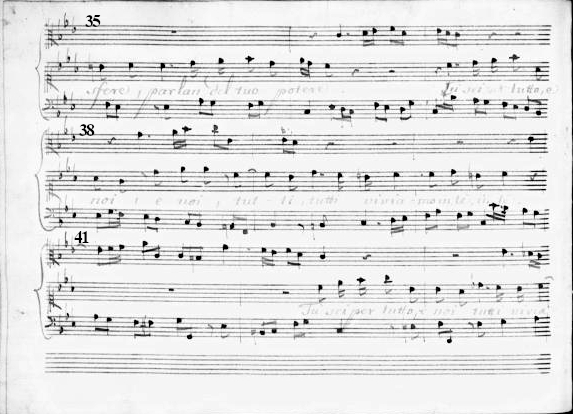

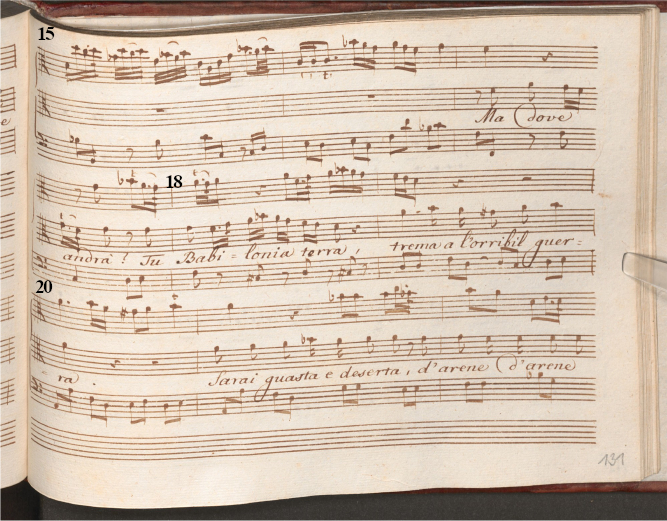

Joy, glory to God - analysed example: Giovanni

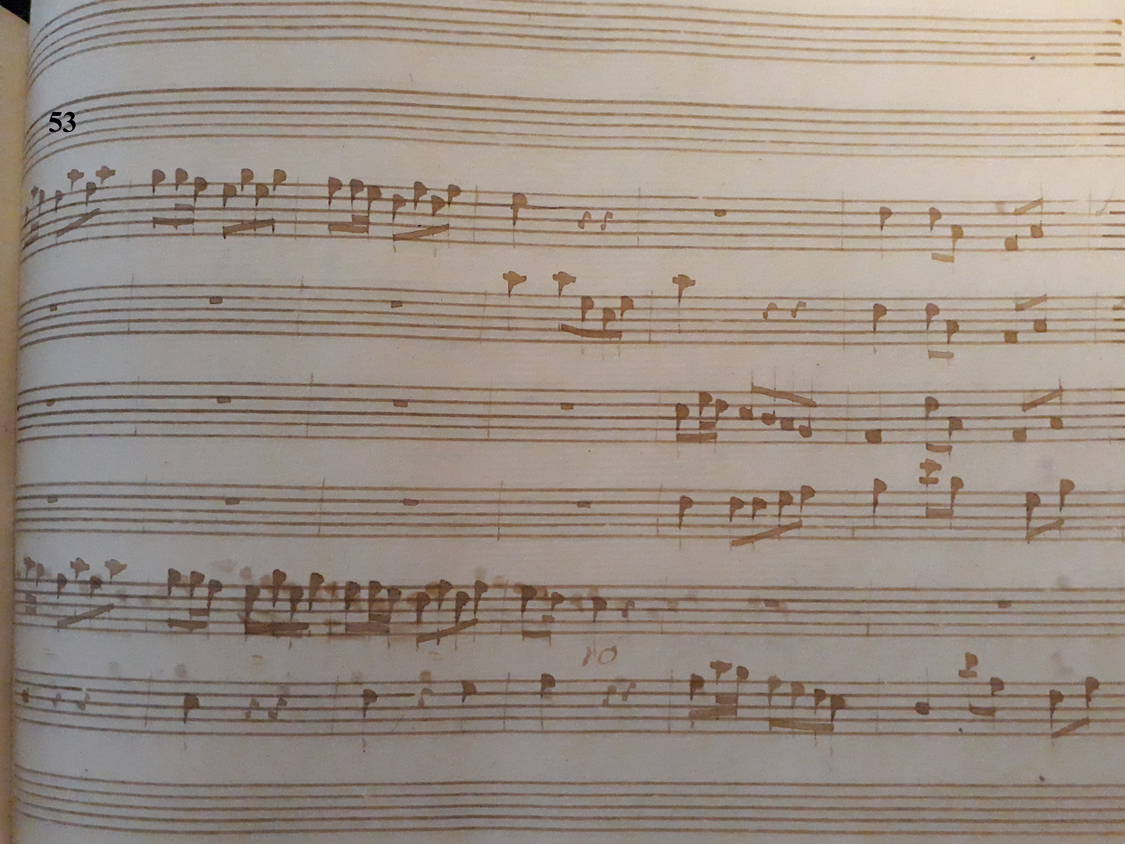

This aria by Giovanni with trombone is the third and last sung by the character and comes at the end of the second part of the oratorio La Passione di Gesù Cristo.

It is truly an aria that gives thanks to God for all his works. After the death of Jesus, Giovanni reassures his relatives, Maddalena and Joseph, telling them that even though they no longer see Jesus, God is in all things and lives in him (Giovanni) as in both of them.

The aria is written for solo trombone, soprano voice and basso continuo (BC). It is an andante in 4/4 (C).

It begins with an instrumental trombone ritornello which introduces the melody sung by Giovanni. The melodic motif can be seen as repetitive and circular (E, D, E, F, E, D, E, F, E, D, E) and seems to perfectly illustrate the fact that wherever Giovanni's eyes set, he sees the divine work: "dovunque il guardo giro immenso Dio ti vedo". The trombone is absent from this first phrase, but joins the voice on the second.

The second sentence bar 16 repeats the same circular motif a lower fourth: "nell'opre tue t'ammiro, ti riconosco in mè". Giovanni then insists on "in mè, in mè, ti riconosco in mè". (in me, in me, I recognise you in me).

The second and last exposition of the text is done with the trombone from the upbeat of bar 22. Giovanni then repeats "ti riconosco in mè" with a long vocalise on "riconosco" without the trombone.

The instrumental ritornello then starts at bar 29 to the central part at bar 35. This ritornello takes up motifs from the introduction, but varies in terms of harmony.

The B part is quite short and has only one exposition of the text. The trombone repeats the melodic phrases sung during the short pauses in the voice. Giovanni exposes just a second time the second part of the phrase bar 43: "tu sei per tutto, e noi tutti viviamo in te" (you are for everyone, and we all live in you).

The trombone has in this aria this rich and generous sound, both reassuring and serious. It supports what Giovanni is saying with these repetitive motifs that give a glimpse of the vast world in which everything is God and God's work.

Introducing and repeating Giovanni's melody at times, one could almost believe in God's voice echoing the words.

The trombone has here a role of illustration, echo and support for the lyrics, as much by its warm timbre as by its melodic motifs.

King David with his harp. Other instruments can be seen next to him: a fiddle, a salterio, and a rebec (or a guiterne). The illumination can be found in Psalm 1 "Beatus vir", in a 14th century manuscript kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France: Paris, BnF, Français 161 f.276

The observation of the table opposite and the graph above allows us to observe the following:

-

The predominance of medium tempi (andante) in all categories, except in devoted love, dominated by largo and larghetto.

-

The prevalence of binarity, with 12 out of 18 arias in C

-

7 out of 18 arias are totally minor (parts A and B)

-

10 arias have their A part in major, of which only 1 (Achia) is major also in the B part

-

The dominant major tonalities are: C Major and F Major

-

The dominant minor tonalities are: D Minor, A Minor and G Minor

-

8 arias are joined by strings

-

The two Geremia arias (salterio and gamba) in Sedecia and the aria of David (salterio) do not have a classical da capo form (ABA), but are written in the following ABAB form, with a different text for each new A and B.

The affects associated with these tonalities according to Charpentier, Masson, Rousseau and Mattheson were seen earlier, when exploring the arias in the categories of sorrow and warlike feelings.

For F Major, Rousseau tells us that it is appropriate for "devout pieces or church songs", while Masson writes that it is "naturally gay mixed with gravity".

In the three arias in this category with this tonality (2 for salterio and 1 for 2 trombones), one can fully feel the lightness of the aria quickly caught up by the seriousness of the lyrics. One of them is a prayer giving thanks to God after he has heard his sufferings. The aria with the two trombones (Santa Ferma) almost joyfully affirms that the love that asks him to deny his God is not love, but a true serpent. In the second aria with salterio, Geremia receives a divine vision of the city of Jerusalem, deserted by its population.

On this graph you can notice that the majority of the arias present an atmosphere linked to the expression of the divine (18). Then come the warlike feelings (12), mainly represented by the trumpet and clarino. And finally, the expression of pain (8), half of the arias of which are accompanied by the chalumeau.

Below is the table of Italian texts and English translations of the arias in chronological order of composition and creation of the oratorios.

Back to table of contents

To next chapter: Professional application of my research

In the table opposite here, we can get an overview of the tempi and tonalities mostly used in these arias. Most of the arias show minor tonalities and slow tempi. I am aware of the existence of many descriptive tables of tonalities and related affects, but as Mattheson wrote,19 these lists were not intended to be used as a dictionary, but rather to give ideas, punctuated by musical examples, to inspire his contemporaries. This is why I am not going to refer systematically to these writings about affects linked to specific tonalities or tempi, but I start from the simple observation of these tables, in my opinion rich enough in examples to lead to a coherent observation of Caldara's way of composing, in order to create a certain atmosphere linked to the affects present in the texts.