Methods

i. Folding the flat sheet

For me, as for Bal, the relationship between sculpture and narrative is inextricable from the architectural. Crucially, it begins with a flat sheet. This flat sheet, whether it be paper for drawing, foam board for modelling or a computer screen for visualising, is the foundation of modern architecture, later becoming a space or a building. For me, the same could be said for making sculptures and writing. I work, almost always, from a flat sheet — not to draw what I will later make, but to fold, pleat or write, or to rub charcoal traces of sculptures already made. Stories and sculptures come from this most basic of rules, the flatness of the sheet becoming dynamic as I activate it with words or form.

Rules, like the initial flat sheet or grids for folding, allow freedom and movement guided by the resulting sculptures or texts themselves — they escape the flat sheet, take on a life of their own, rise up and command space; they push forwards and pull back. The sheet could be paper, metal or even roofing felt, and this dictates, to a certain extent, the form. Due to the nature of the flat sheet, there is often a front and a back to my works, a gesture of dramatisation or staging in the stories they tell.

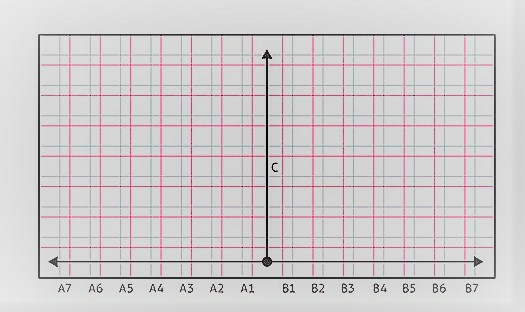

The size of my sculptures is partly dictated by the dimensions of sheets available, though various modules may be joined once folded or pleated to create a larger piece. The sheet is divided into equal vertical and horizontal sections, then folded, first one way, then the other, to create a grid of interlocking pleats (see diagram below) which can be pulled or hammered apart slightly to activate the volume and form of the finished piece. For example, with roofing felt, I begin by sitting on the floor, folding and pleating to raise the flat sheet upwards. I move my own body and the material in an intuitive and physical wrestling match, creating a three-dimensional form on which we both eventually agree.1

ii. Writing the flat sheet

Writing and drawing, too, begin from a flat sheet, and my methods for these and for sculpture form layers in my practice. Often, I begin with a sculpture, raised from a flat sheet, then I make a photograph or rubbing of it. The paper forms a skin between sculpture and image, yet direct contact inscribes it forever there on the paper. These drawings or traces become starting points for texts which I write intuitively, beginning with forms I might see in the lines but writing freely as floating narratives emerge and associative thoughts and memory are activated in the looking and writing process. These are texts not about the sculptures or images but made through them, facilitated by them to voice stories which might otherwise never have been told. There is often a ‘you’ in the texts, shifting between ‘you’ the viewer/listener, ‘you’ (me) the artist, ‘you’ as a specific other person and ‘you’ the sculpture. This engages the relationships between viewer, artist and artwork in a fluid and phenomenological way, with an awareness of body, space and sculpture.

Akin to Bal’s theory, which suggests that direct engagement with a work of art is key to art writing and best extracts its narrative qualities, my writing begins with the visual and material qualities of the work itself, whether they are objects, drawings or photographic images, and from there takes an intuitive approach that allows narratives to emerge out of but not about the work. Bal argues that ‘the closer the engagement with the work of art, the more adequate the result of the analysis will be, both in terms of that particular work and as an account of the process of looking […] the process or work of art […] being the most adequate subject of artwriting’.2

In allowing words to be experiential rather than pedagogical, one may engage differently with the texts and the sculptures to which they relate. It is thus important that my texts are heard, rather than read on the page. Words can drift in and out, and when spoken aloud they are heard before being assigned to memory, a voice left lingering in the air. Sometimes, one might encounter the sculptures independently of the texts, or the texts independently of the sculptures, which forms an entirely different experience and narrative. As potter and writer Edmund de Waal says:

Stories and objects share something, a patina [...] Perhaps patina is a process of rubbing back so that the essential is revealed [...] But it also seems additive, in the way that a piece of oak furniture gains over years and years of polishing.3

In this way, my texts and sculptures share something. They relate to one another in layers — not just in the actual patina on metallic surfaces, but in the way they add strata of meaning to one another, while also revealing their own essential selves, what lies beneath the skin. The Pleating Papers began with pleated paper models, then became photographic images, then texts, then later a series of sculptures out of which I wrote more texts. The narratives in the work are therefore multiple, layered and various. Though The Pleating Papers came from the models. they feed increasingly back into the sculptures, in a relational, ongoing cycle of narrative threads. As the sculptures gain strength in holding narrative by themselves, so the texts seem more relevant in form and content, their layout on the page and the words and stories they contain. The words I write engage with the materiality and form of the objects I make. Themes of architecture, body and matter run through both sculpture and text. Working with both forms permits the reconfiguration and reimagining of narratives in layers of object and text, and the combinations of these are important in the process and eventual outcome.

However, the order in which the various elements of my practice come about is not fixed, and could continue in a near-endless and multifaceted cycle. I often write in sets of ten or more, posing each text both as one part of a larger overarching narrative, and as one of ten possible narratives surrounding the related sculpture. This is not a system whereby Image 2 pairs only with Part I — elements are interchangeable and Image 2 could equally be paired with Parts II or VI. Further, I have included only a selection of The Pleating Papers here: this suggests another narrative entirely to the one that might exist if all ten texts were present, much as one might experience the sculptures without hearing the texts.

The interchangeable nature of these elements recalls Surrealist artist Tristan Tzara and his method of cut-up poems which so scandalised his peers,4 yet freed words from a set order, phrasing or collective meaning. The 1950s painter and writer Brion Gysin similarly cut newspaper articles into segments that he then rearranged to form new narratives, so that ‘permutated poems set the words spinning off on their own; echoing out as the words of a potent phrase are permutated into an expanding ripple of meanings which they did not seem to be capable of when they were struck into that phrase’.5

This same multiplicity allows my own texts and sculptures to be simultaneously personal, specific and ambiguous. They are personal to me, of course, but I hope that when made public, they have universally recognisable aspects, whether emotional or in imagery, and that they invoke memories individual to the viewer. As Bal says of Spider, ‘the memories are unreadable because they are personal, but the works are made public so no longer bound to one person’s history.’6 So, when looking at a sculpture or reading/hearing a text, memories or emotions may be evoked according to the viewers’ own experiences.