METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES

What is at the core of the interpretative process? How could we express our diverse methods and collaborate as a group?

MIXED RESEARCH METHODS

At the departure, group members defined and shared ideas about methodological work processes, and these approaches were developed, modified and used freely during the research period. The range of resources informing a performer's search for expressive means are manifold, and the researchers integrated the resources which seemd necessary to inform their individual artistic projects. The research group experimented with methods for how interaction and dialogue between performers could “(un-)settle” individual expressive practices, based on gaining deeper understanding of performative situations, sites and styles. This included the ability to interpret or translate notation and descriptive indications in a score, to obtain pertinent knowledge from a wide range of sources, both musical and extra-musical, and to combine these with tacit knowledge, imagery, creativity and intuition.

The group as a whole used a variety of methodological approaches:

-

Compiling historical context, performance traditions

Historical sources contain valuable information and texts about the music, lyrics, composer, letters, correspondence, historical recordings, performance traditions. -

Interpretating notation

Exploring all written signs and word indications in the score offers various choices of interpretation, modes of understanding and means of expression. -

Studying compositional elements

Music theory and structural analysis can help gain insight into a work's intrinsic elements, structure, form, and aesthetical contents. -

Re-visiting and re-listening

Attempting to reduce personal preconceptions, deliberately focusing attention on musical elements that might generate alternative perspectives. -

Reconsidering artistic choices/planning/reasoning/consciousness

Performance analysis includes asking questions and making choices on phrasing/breathing, questions of style, characterization, rhythm, rubato, tempi, sound world, textual content, timbre. -

Exploring expressive essence, artistic message or meaning

Drawing on intuition, emotional response, personal experiences which resonate with the composition's expressivity, emotional and aesthetic content. -

Cultivating instrumental means of expression

Applying and developing trained capabilities, experimenting with instrumental techniques in order to meet the artistic demands inherent in the composition. -

Generating visual and verbal inspiration

Creating visual images, narratives, metaphors, analogies, associations, and abstractions to capture and express the composition's contents.

Many of these aforementioned methods were also relevant to the Composer-Performer Collaborations project. In the dialogue-based, co-creative process of composition, improvisation was a vital part of the creative research. It was a highly intersubjective process, in which the development of ideas and new combinations of extended techniques were tested and applied.

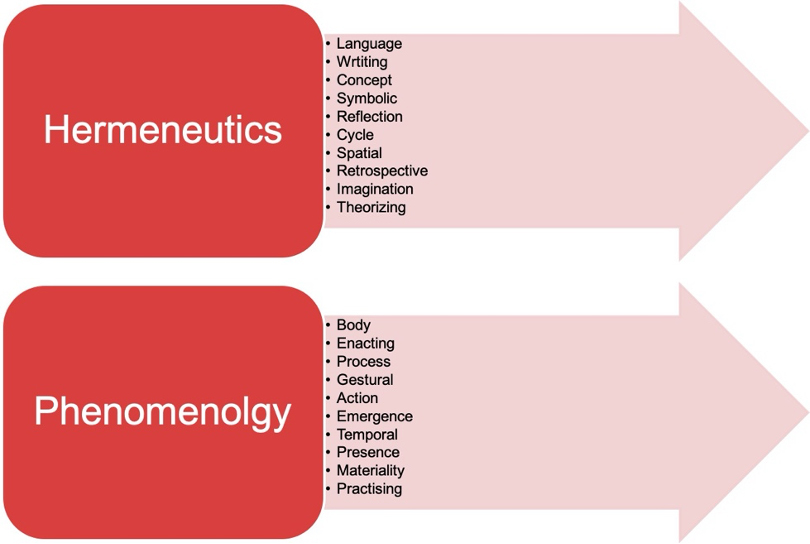

HERMENEUTICS AND PHENOMENOLOGY

Hermeneutics is the study of interpretation. Hermeneutics plays a role in a number of disciplines whose subject matter demands interpretative approaches, characteristically, because the disciplinary subject matter concerns the meaning of human intentions, beliefs, and actions, or the meaning of human experience as it is preserved in the arts and literature, historical testimony, and other artifacts. … Hermeneutics thus treats interpretation itself as its subject matter and not as an auxiliary to the study of something else. Philosophically, hermeneutics therefore concerns the meaning of interpretation — its basic nature, scope and validity, as well as its place within and implications for human existence; and it treats interpretation in the context of fundamental philosophical questions about being and knowing, language and history, art and aesthetic experience, and practical life.(plato.stanford.edu)

The discipline of phenomenology may be defined initially as the study of structures of experience, or consciousness. Literally, phenomenology is the study of “phenomena”: appearances of things, or things as they appear in our experience, or the ways we experience things, thus the meanings things have in our experience. Phenomenology studies conscious experience as experienced from the subjective or first person point of view. This field of philosophy is then to be distinguished from, and related to, the other main fields of philosophy: ontology (the study of being or what is), epistemology (the study of knowledge), logic (the study of valid reasoning), ethics (the study of right and wrong action), etc (plato.stanford.edu)

Throughout history, terminology about music and the concept of a musical work have been delimited by both hermeneutical and phenomenological categories of thought, which regulated the musical work from its production to its reception (Kivy: 1990; Goehr: 1992; Treitler: 1999). These categories address both musicological “gnostic” and performative “drastic” aspects of works through different stages, materials, and a variety of interrelated modes of writing, reading, and enacting (Abbate: 2004, pp. 505-536).

SELF-REFLECTION THROUGH LANGUAGE

What happens when we talk about artistic research? In order to communicate, we need to develop a specific language relating to the artistic material to be explored, while at the same time expanding the space of personal/private experience. One might begin by addressing one’s own language and rhetoric – the habitual use of verbal figures and formulas, including borrowed phrases from others' languages, theories, and narratives.

Often, these habitual forms of speech and expressions work in combination with other modes of expression, including body language, facial expressions, gestures, and imagery. In this way, one’s “own language” includes the entire artistic register which an individual has (Nyrnes: 2006, p. 15).

What does this mean for a performer? Expressive language is acquired by confronting, visiting, and revisiting the “languages” and styles of others. In order to become aware of these internalized habits of expression, one has to be able to identify the bits and pieces of one’s “own language”. Language is not just something one “owns”; it is shared as a common cultural practice. The main “bits” and forms used in daily language are learned, memorized, and internalized expressions embedded in collective practice.

At the same time, when we as individuals use these forms, they become expressions of a personal narrative; they gain a “poetic” quality as they tell the “story of our life”. Thus, our own language always expresses how we understand ourselves. The stories we tell (about ourselves) may be constricted by our anxieties, what we allow ourselves to think as artists, researchers, and human beings. In artistic research it is important to cultivate appropriate terminology. Artistic research requires consciousness about how one develops an assumption (doxa) into an individual belief in one’s “own language” (Nyrnes: 2006, p. 15).

What happens if we talk about art research in spatial or topological terms? If the aim is a deeper awareness of one’s own language, how might we use the notion of “topology” in language as a point of departure?

-

A first step would be to identify the “topoi” within one’s own artistic language, meaning “places passed frequently when following well-known paths”. This might be certain verbal expressions, figures of speech, metaphors, gestures, idiomatic habits, etc.

-

This way, one can describe one’s own position in the landscape of the topic to be explored, like the T-mark used to mark hiking paths in the Norwegian mountains.

-

As a next step, one might draw a map revealing the “forgotten” origins behind the most significant expressions, the T-marks’ position: who put them there, where do they come from, when were they set up? The result might be a network of relationships developed through time, from the first encounter with the artistic material up to the present.

-

Such a map of networks may shed light on each individual’s position in the landscape, which is the “space for unfolding ideas”, as well as on the shared ”sites” and “loci communes” within a topic, such as a specific composer’s style.

REFLECTION THROUGH INTERSUBJECTIVE COLLABORATION

Similar reflections can be applied to all habitual modes of expression, including musical composition, musical interpretation and performative issues. The RESEARCH QUESTION NO. 6 concerning intersubjective collaboration was intended to address these themes as a group, and to assist each other in pinpointing habitual T-marks. The intersubjective collaboration within the research group contained a multitude of meeting places of exchange within the group, as well as external individuals and environments.