II The Consequences — Re-imaging

We organize this chapter around eight themes of Re-Imaging. Each of them reflects a part of the process which we continually investigate and incorporated into our teaching methods and art practices.

Re-placing

Discovering an animal, an insect, a plant or a fungus aurally is something fantastic. Another world suddenly appears and re-places the previous world. Although I don't understand the language of this world, I can hear it. Understanding comes later, if at all, but when that moment arrives, a whole set of propositions opens.

Catherine employs two books to explain this. Both are about sudden and violent animal encounters that radically transformed the authors’ thinking and work (Plumwood, 2002; Martin, 2022). Both accounts describe knowing and yet not knowing, of the human error of being stronger than everything else, and of humbly observing, of understanding other dimensions through a dramatic moment in time. Both authors interweave the scientific and the personal in their narrative, pointing to new perspectives through emotions, trauma, and healing in order to open up other worlds.

In the first book, Natassja Martin, a singular voice in current French ethnology, is in search of an animist cosmology she can reconstruct. What she previously described as a scientist—the animistic interweaving of all things—she now experiences directly. The boundaries between the bear and herself, or what was herself, become blurred.

Similar, and earlier, Val Plumwood writes, in encountering a crocodile

“Until that moment, I knew that I was food in the same remote, abstract way that I knew I was animal, was mortal. In the moment of truth, abstract knowledge becomes concrete.” Further, “Some events can completely change your life and your work, although sometimes the extent of this change is not evident until much later. They can lead you to see the world in a completely different way, and you can never again see it as you did before.” (Plumwood, 2012, p.10-11).

or as Martin writes

“You have to be able to live afterwards with and in the face of that; just live further away.” (Martin, 2022, p.138)

These two authors made us aware of the connections between humans, viruses, and animals as intermediate hosts. This awareness brings with it a reorientation of one’s own individuality and relationship to “the idea of a world that could be habitable”. What we carelessly call “nature” is, in fact, an integral part of us—what does this portend? Can we understand listening as a reciprocally assimilating conversation with nature?

This has pedagogical implications, which become particularly palpable when working with soundscapes. As Altman (1992) has pointed out, recordings are a form of representation, not a reproduction, of sound—recording is already an act of interpretation, framing and estrangement. Combined with the seeming (or claimed) “naturalism” and the “immaterial materiality” (Connor, 2004) of sound recording, this generates a dialectic which is pedagogically fruitful, as it forces us to listen closely and critically and question what we consider to be “the nature” of things (Latour, 2005).

Un-ravelling

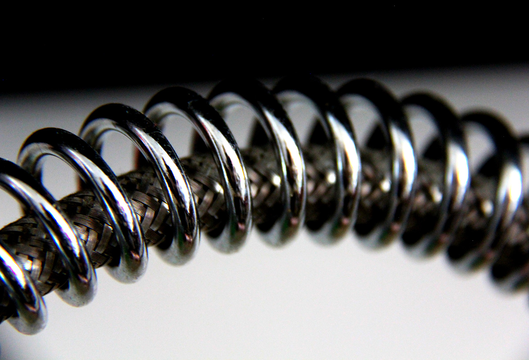

In the analysis of our collected soundscapes and image pairs, we repeatedly divided examples into categories, formed classificatory systems, and made juxtapositions. For future artistic research projects, it is essential not to understand this activity as "purifying” in the sense used by (Latour (1993) to describe a specific scientific activity to produce knowledge, but as an un-ravelling. Rigorous separation denies the buzzing, croaking, chirping, and rattling their right to exist. A soundscape is an agent. Not being heard or seen only hinders understanding of the respective context, which is precisely where the different partial manifestations express themselves. As soon as we try to understand we must also learn how to relate to them.

By “unravelling”, we mean that knotted, condensed or polyphonic structures can be seen or heard in relation to our soundscape recordings and images. Exploring their function, patterns and interconnections does not mean having to destroy or dismantle them.

In this way, new fields of work or art can emerge that refer to textures, connections, or hybridisations. In listening, looking at, un-ravelling, and discussing the manifestations of each “thing”, we will also uncover processes of consensus and cooperation that utilize different ways of seeing and listening.

As mentioned above, there is no “sound of” Sounds. Soundscapes, their sensory qualities and potentials for meanings, all emerge in a process which includes ways of listening, ways of recording, and ways of re-listening. The recording act becomes a selective gesture, which is intended to serve the creation of relationships through shared listening. In this process we may immerse ourselves in the sensory, affective experience of the sound itself, as much as in the semantic, associative and narrative potential of what it refers to (e.g. an action or a process or a thing, or an event).

Re-visiting

Two years after the workshops, Andrea re-visited a place she had been previously and repeated a soundscape recording there:

Soundscapes from Sent in the Engadine, Switzerland.

Water splashes. At the same time,

the metallic sound of the tube resounds.

A socket made of brass. A bright whirring sound

that changes the environment through its association with water.

The intervening time has sensitized us

to match such interventions with our ability to perceive.

To be able to classify them.

Where does the water flow from into the fountain basin?

Who do I see in the middle of the village square, and by whom am I seen?

Re-tuning

COVID-19 abruptly plunged us into a reality that seemed to have been borrowed directly from dystopian science fiction stories. At the same time other narratives emerge, echoing speculative fiction, with authors around climate (Ursula le Guin), racial and gender issues (Octavia Butler, N.K. Jemisin), but also a new narrative exploring relationships between and beyond humans (i.e. Natassja Martin, Vinciane Despret).

Reflecting upon these issues and the workshops, Catherine wonders if they were themselves collective speculative narratives, in the sense that they were initiated by the process of re-tuning to a familiar and nearby place or situation, but in the act of listening and recording this familiar place was made strange again, rendered and kept “in-between” the sounds (audio) and the images (stills). In Andrea’s opinion this is a praxis of artistic research in its own right, a re-tuning oriented by the interaction between the soundscapes, images, and digital classroom in the workshops.

Inter-vening

Looking back, we took on the task of recording soundscapes in a time of uncertainty. By filtering out sound files we inter-vened into the continuum of space and time and then, by adding still images and an index, the files began to develop a life of their own, and this is true whether they are left slumbering on a hard disk or brought out and shown.

Re-interpreting

V. Turner describes liminality as the intermediate state of individuals and groups between two stable situations. This intermediate or threshold state is accompanied by rituals, such as entry and exit rituals, with other rules applying in-between them. This results in the proximity to Michel Foucault's concept of heterotopia. Given the exceptional social context of COVID-19, we can understand the organizational dispositive of the workshops as contributing to the emergence of a threshold state.

Re-cording

The acoustic landscapes re-corded in our workshops have an immediate directness, whether they are tinkling bubbles in a glass of water, or the demolition sounds of a house. They are and remain existential, truly reflecting the term "re-cord" (like the rhythm of the heartbeat). And not to forget what lies in-between: a microphone, a recording device and a human being who tries to connect physical space with their own imagination. The act of sound recording is not without its pitfalls, as it can lead to an extractivist, even exploitative gesture in which sounds become the raw material for production, entertainment and "cabinets of curiosities". But it is precisely this curiosity of sounds that can bring us together as we seek to understand and share them, and each other’s ideas. During COVID-19, we had to retreat to private rooms to communicate digitally with one another. By opening up to each other visually and aurally in this curious and trusting way, we not only turned back on ourselves, but at the same time bonded in friendship, even if it may be temporary, as a community of fate.

This extraction and objectification has a purpose and genuine attractiveness. The world of sound is fascinating and diverse, and, following Chion (1998), withstands the simple attribution as “sound of”. Instead, as the proponents of musique concrète emphasized, each sound has a “musical” potential in and for itself. And this is a very human driving force behind the extractivist action of “capturing” sounds: to make them “presentable”, shareable, available for further processing, as a necessary step in a communicative act. But the pitfall of fetishization lurks in such use of sound, cleaned from all possible “impurities” of the original location by the recording act to become components for “sound effects”, where “effectiveness” is prioritized above all. And contrary to images, there is usually no need to ask for permission or even understand the context and meaning in which the recorded sounds emerged.

De-parture

Could something similar happen in the situation of the physical workshops? After the lockdown we began to consciously shift the physical space we were in. As the body shifts its awareness by walking off campus into a nearby parkland, the pressures of everyday student life dissolve into a curious openness to the environment. The time given to connect with and then exchange ideas about the landscape sparks a diverse and humorously touching processuality. Students de-parture to set themselves tasks that go far beyond their initial questions; we are connected in a community.

We also encountered this phenomenon in hybrid situations: Participants began to support each other and work together. Through the internal collaboration platform, a channel for sharing remained open and was actively used. We returned to everyday life but in a converted way.