5.2 Try-out 2

Title: Choreomaniac seeds - Vol. I

Performers: Silvia De Teresa - piano, voice and movement; Niccolò Angioni - live electronics.

Date and time: 27th of November 2024. 16:30-18h.

Programmed in: “CAN YOU HEAR THAT?! Session 1”

Space: HaagsPianoHuis (The Hague, NL)

This exploration builds on the previous performance try-out and presents an improved version, incorporating key adjustments based on feedback and reflection. It is part of a series of performances curated by four NAIP students - Ron Aviv, Pietro Caramelli, Sigrid Angelsen, and me - at HaagsPianoHuis. The performance placed a strong emphasis on refining the expression of anger and vulnerability while remaining conceptually rooted in Valencia’s catastrophe. This version incorporated a live conversation between audience members during the performance itself, encouraging collective reflection and further dissolving the boundaries between performers, observers, and participants.

Index of try-out 2

5.2.1 Description of the process

5.2.2 Documentation

5.2.3 Comparative analysis

5.2.4 Reflection

5.2.1 Description of the process

Similarly to Chapter 5.1.1, the initial focus will be on the process leading up to the performance, followed by an examination of the performance itself.

The process

During this try-out, the main goal was to further develop the concept that began to take shape in the previous performance. The overall concept and dramaturgical units remained largely unchanged, though some experimentation took place, particularly during rehearsals with Niccolò. We adjusted the durations of certain units, shortening the classical seed while extending the movement improvisations, considering the feedback collected in the last try-out. The key addition to this version was the introduction of a new dramaturgical unit: a conversation between audience members, integrated as part of the performance itself.

Given the limited timeframe of just 20 days before the performance, the process was significantly shaped by time constraints. Rehearsals were carefully planned to ensure a pragmatic approach, allowing ideas to be refined efficiently within the available period. Choosing not to make major changes was essential in maintaining a clear conceptual focus, ultimately enhancing the coherence and effectiveness of the intended expressions.

Throughout the movement sessions, I focused on expanding my range of motion to enrich my repertoire of gestures. This exploration involved two contrasting approaches: on one hand, I experimented with expansive, wide-ranging movements, fully opening myself to the space and pushing the limits of mobility. On the other, I investigated movement within a highly confined space, observing the smallest possible motions my body could generate. By expanding and contracting within this limited space, I aimed to explore vulnerability (Annex F, entry 16th November). The following videos illustrate my explorations of anger and vulnerability:

5.2.2 Documentation

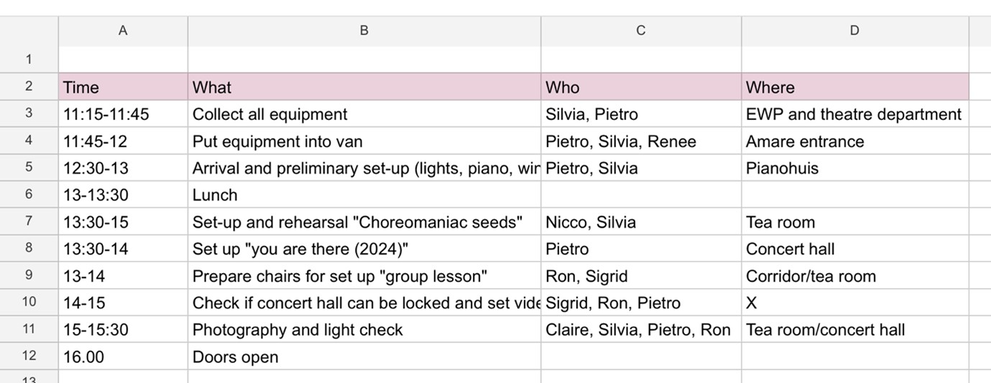

The following documentation can be found below: a recap video of the performance, photos of the performance, a selection of my project journal, the draaiboek (or script) for the day of performance, and relevant audience’s feedback.

Recap video of the performance

|

Component |

Divergences |

Similarities |

|

|

Physical/dynamic components: the venue |

Venue |

Different location. Smaller space, white walls. |

Indoor location. |

|

Performers (amount, disposition) |

Performers very close to each other and in the centre of the room. Starting point of performer with hand in the air was at the end of the room, so it took longer for the audience to realise I was there. |

Same number of performers. Only fixed space was for live electronics and piano. |

|

|

Scenography: set design, props, styling, lighting |

Props: no white shirt on the floor. No traditional Valencian neckerchief. Lighting: more luminous due to white walls. |

Styling: Same costume. Wet hair. Lighting: Same colour, same disposition. |

|

|

Audience disposition |

Audience surrounding piano and live electronics in the centre. |

No designated space for them, freedom to move. |

|

|

Process timeframe |

20 days. |

|

|

|

Abstract components |

Concept |

Understanding audience conversation as part of the performance itself: hierarchical shift. |

Anger, vulnerability, political protest and hyperproductivity critique. |

|

Narrative |

Anger and vulnerability, connecting with audience, classical reconstruction seed and audience conversation. Different stage of the grieving process: this time more externalized. |

Valencia’s floods, event based. |

|

|

Symbolism |

Circular element (e.g. walking in circles, conversation in circle): fluidity and repetition. Lower position of body: hierarchy switch. Valencia’s hymn: unity, community. Hands in the air aggressively reaching out: people from Valencia suffocating. |

Arpeggios on piano and circular motives on voice: fluidity and floods from Valencia.

|

|

|

Performative elements |

Sound: Piano, live electronics, voice |

Piano: higher quality of playing and improvising overall. Recurrent arpeggios on improvisations. One improvisation faster and with a groovier rhythm. Improvisation is not always reflecting melancholy or sad/slow mood. Live electronics: greater importance during movement improvisations, Scriabin’s caesuras with improvisations, and audience conversations. Voice: less glissandos and tone fluctuations. |

Piano: no major changes in mood and tonality. Live electronics: provides the base and gives continuity in texture -or soundscape- and tonality. Voice: range of voice not extensive. Very melodic. Singing major 7th often. |

|

Movement |

Longer duration. Position of the body lower and head looking downwards. Eye contact arrives later. Range of expressive means expanded in anger and vulnerability. Movement more invasive and faster (e.g. gesture of hands towards the audience). |

Wanting to control my movements too much, making it look forced or fake. Small bouncing detected while wanting to move from one place to the other. |

|

|

Text |

Started earlier in the performance. Combined with movement improvisation only, so less information to focus on. |

Same recited text. |

|

|

Disciplinarity |

Audience conversation becomes transdisciplinary. |

Interdisciplinary. |

|

|

Interactions (between performers, with the audience, and between audience members) |

Greater interaction with Niccolò. Physical touch with the audience. 4th wall broken at a later stage. Audience conversation: part of the performance, interaction between audience members. Nicco and I still improvising in the meantime. |

Interaction with audience: encouraged people to move from their position to a more uncomfortable one (on the first try-out, to the centre of the space; on the second, to engage in a flow of collective walking around the space). |

|

|

Audience participation |

Walking in circles around the space. Conversation with other audience members. |

Being guided by my hand, walking/moving towards somewhere. Feedback on the performance. |

|

|

Pacing/flow |

Faster pace during the piano playing, slower in the movement improvisations. Narrative’s rhythm sometimes feels broken. |

Piano piece feels too long. |

|

|

Emotional and experiential elements |

Atmosphere |

More intimate, greater connection. More immersive, the space is part of the performance. |

Intriguing, surprising, touching. |

|

Engagement |

Greater engagement in conversation, felt less tense. |

No extreme reactions, but rather cautious ones. Around half of the people at least shared their thoughts. |

|

|

Impact |

“Very powerful”, “I've never been touched by the one performing”. Irene, present at both performances, felt more actively involved here. |

“Touching experience”, “Truly inspiring”. |

|

Another key reflection that emerged during the process was the desire to convey anger through silence. Rather than approaching movement through a simplistic dichotomy - where anger is expressed through shouting, tensed facial muscles, abrupt gestures, or running - I sought to explore how subtle movements and internalised emotions could communicate a more nuanced and complex range of expressions.

During rehearsals with Niccolò, he proposed several alternatives for structuring the audience conversation in a way that allowed participants to choose to engage or simply observe, while also giving them time to process what was being asked of them (Annex F, entry 20th November). This was a strong example of a genuinely collaborative working process. Another notable example was the development of the conclusion of the classical seed and its transition into the audience conversation. Niccolò suggested incorporating the final piano chord into the electronics with a specific effect, creating a smoother and more cohesive connection between the sections. We experimented with several options during the rehearsal and determined which one was the most suitable.

The biggest challenge in this process was reconsidering the text and working on it alone. I was unsure whether to adjust its content and message. I wondered whether to set aside the direct imagery of what happened in Valencia and instead focus more on elements related to choreomania and my drive for hyperproductivity. To navigate this dilemma, I began creating a mood board for the text, drawing inspiration from the poetic work of Valencian poet Vicent Andrés Estellés (1924–1993). This process is documented in the journal entry from November 25 in Annex F.

In addition, the venue for this performance was different, and I did not have the opportunity to rehearse in that space beforehand. This made it challenging to envision how movements would unfold or address practical concerns, such as the placement of performers. Considering these alternatives was especially important after the reflections from the previous try-out. I intentionally placed the piano off-centre, as I did not want it to be the focal point, yet the audience naturally gravitated toward it, unintentionally leaving Niccolò on the periphery. These spatial considerations were crucial but were only addressed toward the end of the process - something that would have been much easier to manage if they had been planned earlier.

Towards the end of the process, my movement sessions focused on expanding movement possibilities by rehearsing without music. This offered a completely different perspective on how I experienced my body’s movement within the space. Additionally, I practiced envisioning a large audience, as in the previous try-out, the close proximity of people caught me by surprise. To simulate this, I filled my room with objects and obstacles, moving around them without touching them (Annex F, entry 26th November). This short excerpt captures a glimpse of this exploration. Additionally, I include an example of a free improvisation, which is normally how I start warming up when beginning a movement session:

The performance

The disposition of the performers and stage was adjusted for this performance. This time, the piano and live electronics were placed close together at the centre of the space. As the audience entered, Niccolò was already facing the opposite direction, leading them to instinctively move around the central stage. However, at the very end of the room, I was positioned on the floor with my hand pointing upwards, creating a sense of shared space and ambiguity about where the audience should position themselves.

In this try-out it is hard to determine the interaction between disciplines because that implies that there are distinct disciplines. However, sometimes what happens is neither movement nor sound, and we move in the terrains of transdisciplinarity. This means that distinctions between disciplines cannot be made so easily because the borders are blurry, they have dissolved.1 For example, during the audience conversation, a hybrid between a dialogue and an artistic piece was generated by participants’ choices: the right moment to intervene, the right comment to make, the speed at which they talk, their tone… etc. All these choices make their individual interventions an artistic collective happening. Is it a dialogue? Is it a collective spoken word performance? Is it a choreography from one speaker to another in an attempt of completing a collective storytelling?

On the other hand, the interaction between performers was particularly strong, especially during the classical seeds and the improvisations with voice, piano, and live electronics. This try-out saw a much deeper connection between performers and the audience. During the movement improvisation, I first engaged in intense yet vulnerable eye contact before slowly approaching and gently touching their arms. This gradually evolved into a collective circular movement around the stage, with everyone eventually joining in. In this way, the audience naturally became part of the performance space, blurring the line between observers and participants.

Audience feedback

The audience conversation this time was a part of the performance. It was comprised of two main blocks: one where many simultaneous conversations emerged between close-by audience members/participants, and another where everyone formed a big circle and were given the choice to share or enjoy the silence. Unfortunately, the camera stopped recording at 29’59 and the whole section was lost. However, I still have the feedback from the collective feedback session we did at the end of the three performances2, the phrases I wrote down from the feedback I remembered during the performance, as well as additional feedback I received through text messages after the performance by audience members.

The feedback collected this time was highly insightful. Some of the keywords that surfaced from the feedback collected in multiple ways were: “very touching”, “captivating performance”, “very powerful”, “incredibly brave”, “confronting”, “intrusive”, “courageous”, “beautiful”, and “inspiring”.

Whereas some of the audience members agreed that the most surprising and impactful moment of the performance was the very beginning, when I was “curled up”, and how I “moved from there to an expression of anger”, others felt this impactful moment when I sat on the piano and started improvising and playing the classical piece.

However, audience members also found it “confronting” in different ways. For one, it was confronting because, conversely to a concert where you sit and enjoy, here “suddenly you are really part of it”. For another participant, the eye contact was the element which made it feel confronting and intrusive. She shared that, on one hand, you feel acknowledged and important, but on the other hand, you also feel forced to feel something. You “feel steered towards something you might not want”.

Similarly, another attendant shared that “the interactive part was more challenging”, referring to the part of the performance when I made physical contact with the audience and engaged them into a walk in circles around the space. She felt I started expressing anger and pain, which then evolved into despair and indignation, which finally evolved into wanting to create community and collective movement. This was something she felt a bit contradictory, as she felt “confronted with shock, and the next moment [she] was invited in”. She shared that this would “probably work in a longer performance where the audience has the time to move through the different emotional stages and process everything” (Annex F). However, others found it very powerful and said they had never been touched by the one performing before.

Another very helpful feedback she gave was that the spoken word was “a bit too much”, and that narrowing down the text to one (or a few) core message(s) and using repetition would enhance its effectiveness in a performance. She feels I have “so many important things to say, but an audience has limited ability to focus and [she] couldn’t take everything in” (Annex F).

Finally, two other participants made very interesting observations. The first one thought that an interesting aspect of the performance was that some moments he was thinking: “Who is the performer? Who is the observer? Because you could see it either way”. The second one said that she felt “a very strong connection with the audience”, and that this performance was the closest she had ever been to someone performing being so true to themselves and opening up as they were.

5.2.3 Comparative analysis

To clearly illustrate the main differences and similarities between the first and second performances, the following table has been prepared. The comments specifically address the second try-out, and more specifically its relation (similarities and divergencies) to the first one. The main four components are physical/dynamic components, abstract components, performative elements and emotional and experiential elements.

5.2.4 Reflection

A key development in this process was the introduction of a new dramaturgical unit: the conversation between audience members - or rather, participants. This addition was far more than just another structural element; it fundamentally reinforced the idea that the performance could not be fully realised without their input. During the conversation, they became the performers, while I stepped back to observe the intricate choreographies that emerged from their interactions. Their choices in timing, their collective listening, and the organic flow of who speaks when, all became essential components of the piece itself.

During the movement improvisation, I felt a strong need to make eye contact with the audience, deliberately breaking the fourth wall in an intrusive way. At first, this was incredibly difficult - I was forcing an invisible, gestural conversation with an unfamiliar face, creating an immediate and intense connection (or rejection). This made me feel deeply vulnerable, fully aware that all eyes were on me. Yet, at the same time, I wanted to connect with each individual, knowing that my gaze might be confronting. I found myself caught between two contrasting emotions: the one being vulnerable, and at the same time, the one intruding.

Audience feedback reinforced this perception. Many described the eye contact as confronting or challenging, making me reflect on the inherent power dynamics of performance. The performer is inevitably subjected to the collective gaze of the audience, placed under the spotlight. However, when this dynamic is reversed - when the performer actively directs their eyes at an audience member - it is perceived as intrusive. This inversion of roles made me question traditional performance structures and what it truly means to be a performer.

In contrast, the physical interaction - lightly touching participants - felt unexpectedly comforting and even embracing. I was aware that I was crossing boundaries, so I remained careful and intentional, yet the experience felt natural and warm. This moment, like the rest of the movement improvisation, was entirely unplanned. Similarly, when I guided the audience into a collective circular movement, it happened spontaneously, emerging organically from the shared space we had created.

Throughout the process of shaping this try-out, I noticed a gradual shift in how I perceived the process itself - as a form of choreography. Kélina Gotman’s insights on expanding the understanding of choreography prompted a deeper, more subjective transformation. I became increasingly aware of the movement embedded in everyday actions - the choreographies of crossing paths with strangers, the rhizomatic flow of thoughts, and the shifting dynamics of emotions - all forming intricate, unspoken choreographies. This perspective reshaped my approach, allowing me to see choreography as a wider phenomenon.

Overall, I was satisfied with the improvements in musical quality - not only in the interpretation of Scriabin’s classical piece but also in the improvisations with Niccolò and the vocal explorations. This highlights the crucial role of process and the need for adequate time to internalise and refine artistic elements. Allowing space for ideas to evolve and settle was essential in achieving greater depth and cohesion in the performance.

Building on this idea, the timeframe leading up to a performance plays a crucial role in the creative process. I see it as an independent component in performance-making, as it significantly influences the decisions made throughout the process. However, in Gester’s Map of Components, this factor is scarcely acknowledged. Considering that his framework is a guideline for the process of creation, I take this opportunity to expand on his framework by emphasising the impact of time constraints on artistic choices throughout the process of shaping performances.

With this heightened awareness of subtle movement and choreography came a strong desire to express anger through silence - allowing gestures to hold intensity and depth without relying on exaggerated or conventional expressions. This challenged me to explore a more nuanced and refined physicality, resisting the temptation to illustrate emotions in an obvious way. During a conversation with Pietro Caramelli, co-curator of the series of concerts at HaagsPianoHuis, he reminded me of a previous performance I created for the Performance and Communication course, in which I remained completely silent. He noted how the absence of words made the piece feel incredibly powerful and even aggressive. His observation led me to reconsider the impact of restraint in movement and to further explore how silence, combined with controlled physical expression, could create a more profound and visceral embodiment of anger.

Rather than viewing disciplines as separate entities, this try-out revealed how sometimes, presence and connection are more significant than a categorisation. At times, what unfolds is neither movement nor sound in isolation but something that exists in between, beyond defined disciplines. This is where the notion of transdisciplinarity becomes essential - where traditional boundaries dissolve, and experience takes shape in a more fluid, interconnected way. Much like choreomania, certain moments within the performance escape clear definition. Words may attempt to frame an event, but they often fall short of capturing its full complexity. What remains is the immediacy of presence, the shared energy in the space, and the silent yet profound exchange between performer and audience.