Without attempting to provide an exhaustive overview, the following analyses of four representative cases, discussed with increasing depth, aim to shed lights on how affordances and redistributions unfold in practice. The analyses and accompanying diagrams are not intended to capture the full multivalence of each piece, but to foreground aspects most relevant to that aim.

3.1. Symphony No. 9 (1824) for orchestra by Ludwig van Beethoven

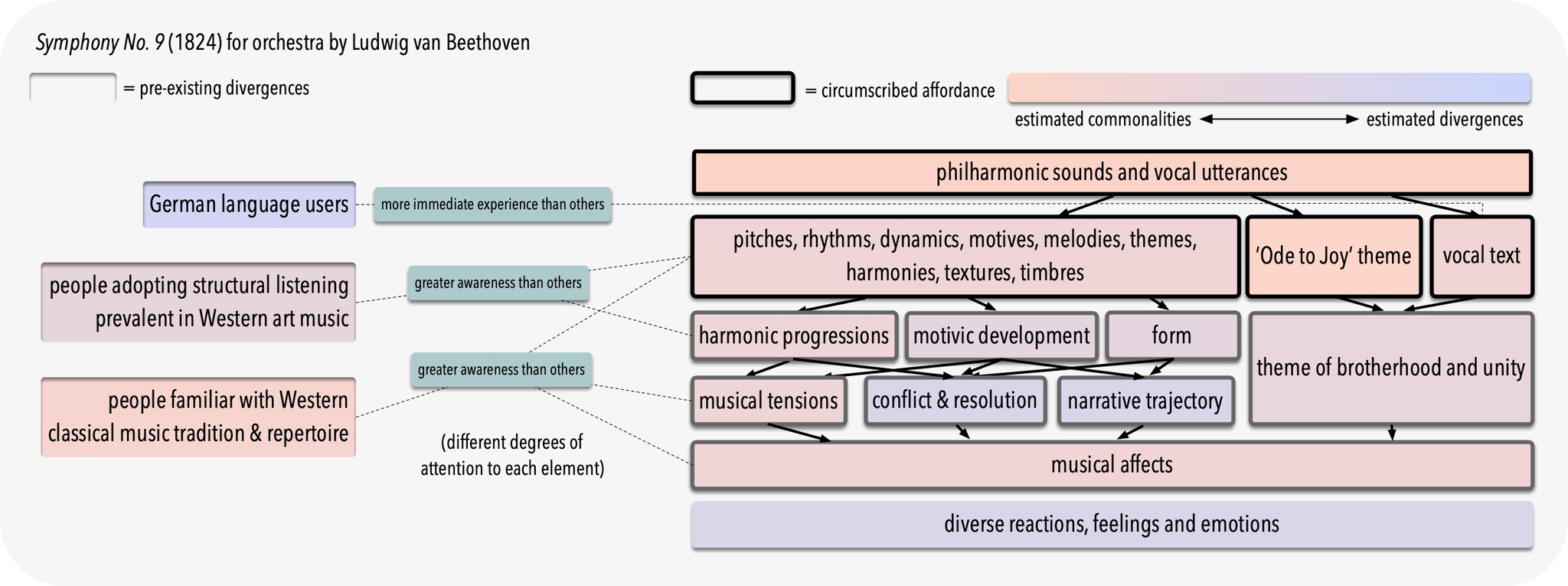

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, composed within the cultural context of 19th-century Europe, serves as a prime example of Western art music from the common practice period. As illustrated in Fig. 1,7 the symphony’s circumscribed affordance encompasses the stimuli and abstractions conventionally recognised as musical elements of the era. These elements, including the notated abstractions of pitch, rhythm, harmony, dynamics, tempo and instrument timbre, are widely understood and practised by musicians, critics, and audiences. They are further combined into themes, motifs, and structured forms, all contributing to the teleological shaping of tension and release within the tonal system, culminating in a narrative trajectory characteristic of 19th-century compositions.8

Of note is that these musical features did not occupy an equal position within the symphony’s circumscribed affordance. For most 19th-century European audiences, surface-level parameters such as pitch and rhythm, along with the large-scale tonal-dramatic trajectory of tension and release, were more readily apprehensible due to their alignments with the prevailing natural and socio-cultural orders. By contrast, the intricacies of motivic and thematic developments—a stylistic feature of Beethoven’s time—demanded greater musical literacy and were therefore less likely to be consciously grasped and appreciated by everyone. Consequently, in comparison with the basic elements and the overarching narrative arc, tracing motivic and thematic developments can be regarded as situating relatively closer to the domain of preferred affordance, its status visualised in Fig. 1 with grey boundaries.

- Regarding the diagram: Boxes on the left, distinguished by inner shadows, represent various aspects of the differing conditions among audience members. Boxes on the right, with varying border darkness, suggest affordances of the musical performance with varying degree of circumscription. The warmth of their colours, in turn, corresponds to the estimated extent to which such affordances are generally shared among the audience.

As these diagrams are for illustrative purposes, not all details carry equal weight. Readers should exercise caution to avoid over-interpreting these distinctions, especially regarding the estimated commonality of affordances. It is crucial to acknowledge the inherent messiness of artistic research. As the composer confronts the challenge of grappling with the properties of musical materials while recognising the impossibility of attaining comprehensive knowledge, a critical factor in the experimental process lies in advancing propositions that possess an element of falsifiability conducive to further examination. - Performers’ interpretations, based on the notated abstractions, certainly also contribute to the higher abstractions of musical gestures and to the tension and release, creating richer affordances and circumscribing them further.

Despite these differences in accessibility, the hallmark of this cultural milieu remains its music creators’ ability to circumscribe affordance. The widely shared tonal conventions gave composers significant control over the anticipated responses of concert audiences across Europe.9 When combined through conventional compositional procedures, the basic elements could come to signify abstract concepts such as conflict and resolution, shaping for listeners an affective journey from an intense beginning to a triumphant conclusion. Furthermore, the well-established forms and materials enabled finer-grained control over elements across multiple levels of abstraction, allowing for a greater freedom in nuance formation across perceptual, cognitive, and emotional dimensions.10 For connoisseurs, it was all the more apparent, as they may discern subtleties like the unusual treatment of the final movement involving vocal parts.

This shared tonal framework, however, did not eliminate heterogeneity among the audience. Personal factors such as prior experiences and socio-cultural background continued to endow each listener with unique affordances, leaving space for diverse modes of engagement as well as individual emotional responses and interpretations.

In Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, we observe a typical pattern in which the more widely accessible an affordance is, the more closely it approaches a baseline circumscribed affordance. At the other end of the spectrum, only a small group of listeners—Beethoven himself possibly among them—were capable of engaging with the work’s entire scope of preferred affordances.11 In terms of redistributing what can be sensed by whom, its tonal musical language largely adheres to and reinforces the conventional distribution of the sensible characteristic of 19th-century Europe, particularly in connection to the bourgeois class. Yet the deployment of vocalists and the “Ode to Joy” theme introduced significant redistributions: it welcomed lay listeners or commoners drawn to accessible melodies, privileged German language users who can immediately grasp the vocal text, and resonated with listeners moved by its message of brotherhood. Taken together, the symphony serves to reveal the layered complexities of affordances in musical works, while simultaneously demonstrating how the composer’s formal operations and material choices refashion the distribution of what can be sensed by whom in a particular socio-cultural context.

- A similar, though not identical, case is found in contemporary popular music, which still heavily relies on the tonal system inherited from Western classical music, today broadly disseminated worldwide.

- There is a wealth of literature supporting this argument. Perhaps the best-known example is Meyer’s (1956) claim that stylistic conventions generate expectations and enable nuanced emotional effects through ‘deviation from the norm’. For the present discussion, note that, to derive ‘meaning’ from a deviation, familiarity with the norm is a prerequisite.

- This speculation is, of course, complicated by Beethoven’s deafness in his later years, though it does not diminish his conceptual grasp of the work’s affordances.

3.2. 4’33” (1952) by John Cage

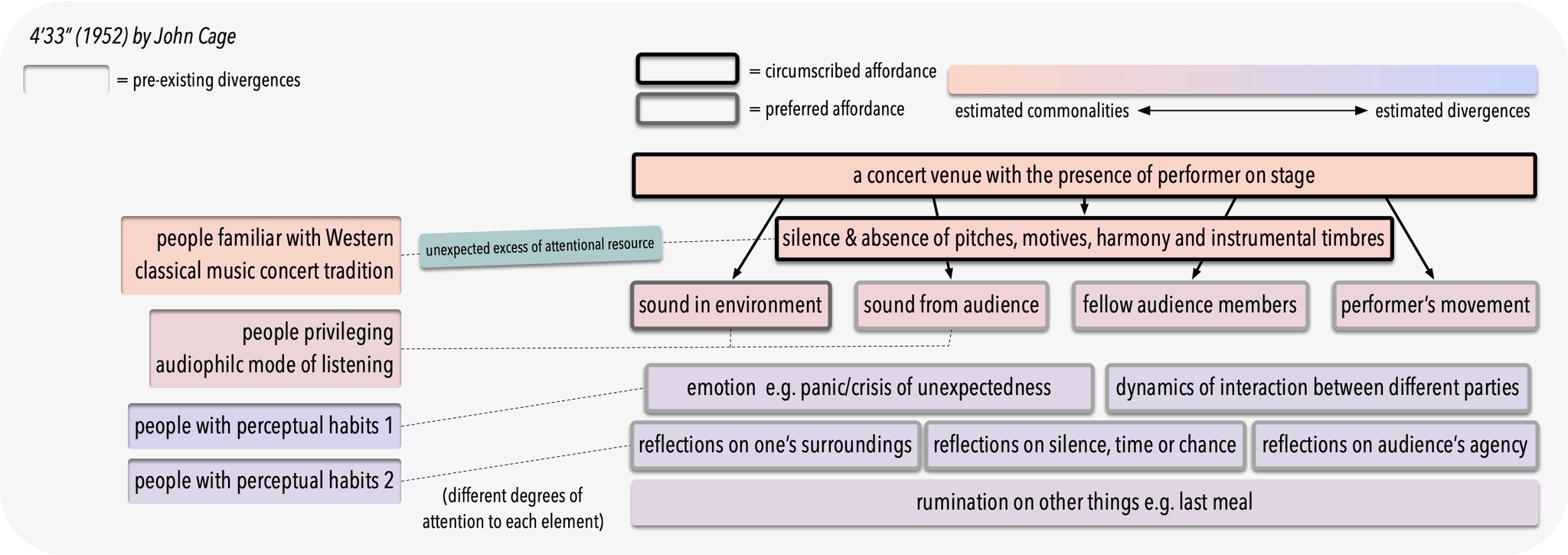

4’33” presents a unique case in relation to circumscribed affordance: it merely instructs the performer(s) to remain silent on stage for the piece’s duration, with certain versions incorporating actions in the form of opening and closing the piano lid. Drawing on the most widely held expectations in the concert setting, the piece’s formal operations first and foremost circumscribe the basic recognition and experience of the unusual absence of conventional (musical) sounds on stage, shown by a box with black boundary in Fig. 2. In this sense, 4’33” counts as a prime exemplar of circumscribed affordance established through the inventive and effective use of an unexplored cultural commonality among audience members—not through a shared familiarity with the tonal music language, as with Beethoven, but through the collective understanding of what a concert entails.

Alongside this, the random and spontaneous sounds within and outside the venue may also be incorporated into the circumscribed affordance, but they do not acquire the same fundamental status as the unusual absence of sound, despite Cage’s intention.12 This is because their incorporation arguably necessitates a different and less prevalent set of listeners’ preconditions, including a mode of listening that highly privileges sound as the dominant element of the concert experience, while downplaying a conventional mode of attention to events on stage.

Above all, what renders the work singular is its barely existing formal operations. Through the simple but powerful act of removal, it foregrounds and invites engagements with what remains in the concert situation—incidental sounds, social dynamics and participating agents. This shift places the bulk of sense-making for the laid-bare socio-cultural scaffolding on the listeners themselves, and on those who possess cultural capital—critics, musicologists, performers and educators—who further influence the circumscription of how the work is perceived and interpreted.

Since there is no single correct way of experiencing the work aside from recognising the abnormal absence, its minimal circumscribed affordance permits a broad range of responses and interpretations from listeners of various backgrounds. In terms of what can be sensed by whom, the work redistributes the established order of perception in an open-ended manner: while culturally literate listeners may derive deeper meanings from the piece, others less acculturated to the dominant Western listening practices may also generate highly original interpretations.13 In the absence of higher-level circumscribed affordances that further structure the experience of absence and/or environmental sounds, the meanings that emerge ultimately reveal more about the listeners themselves.

- In an objectivist way, Cage describes the musical work as consisting of ambient sounds. “It is from Cage's own writings and published interviews that most interpretations of 4’33" are made, that is, that the piece does not consist of silence but the ambient sounds which naturally occur within the environment and among the audience.” (Fetterman 1996, 71–2)

- Although the socio-cultural orders that police interpretations may remain strong, the work’s circumscriptive openness affords less acculturated listeners a greater share of agency than would be the case with Beethoven.

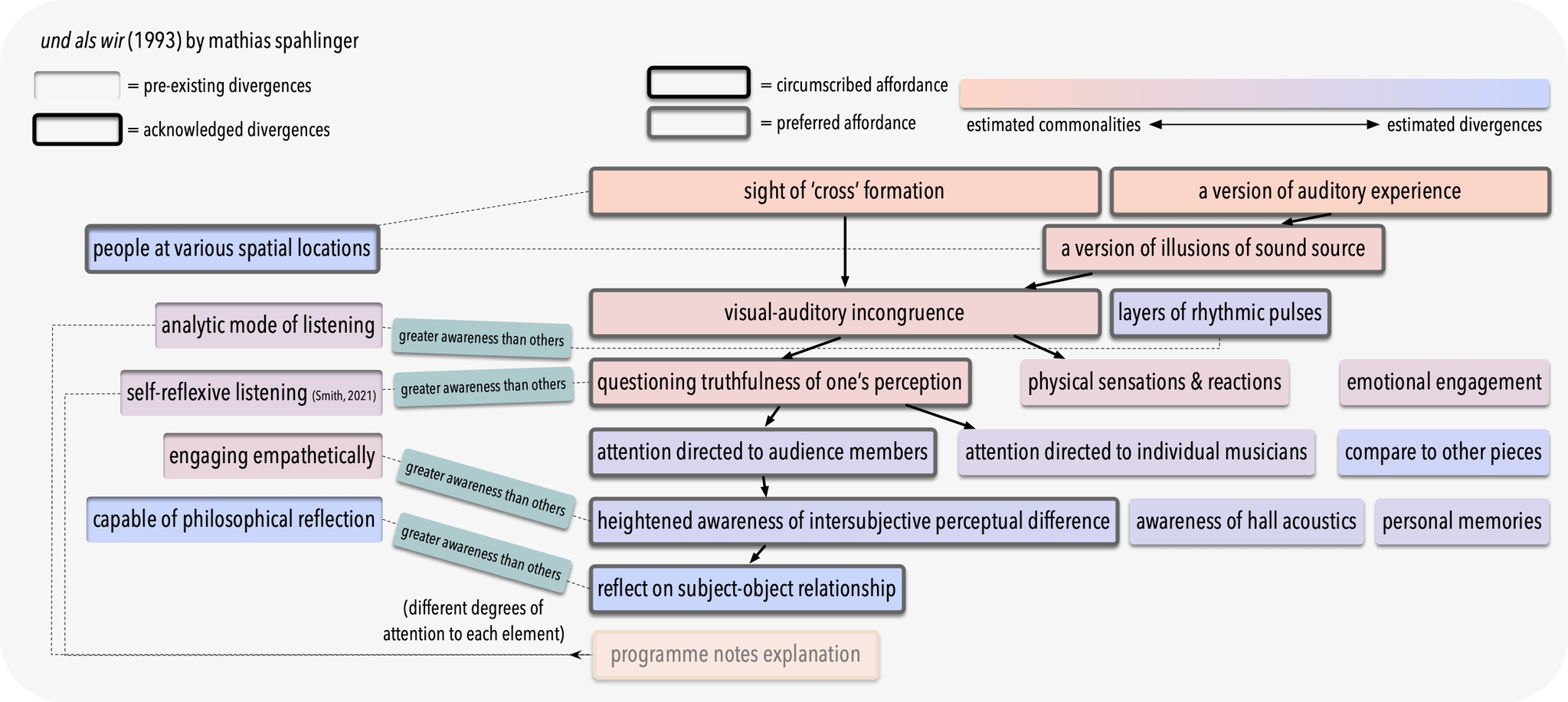

3.3. und als wir (1993) for 54 solo strings by Mathias Spahlinger

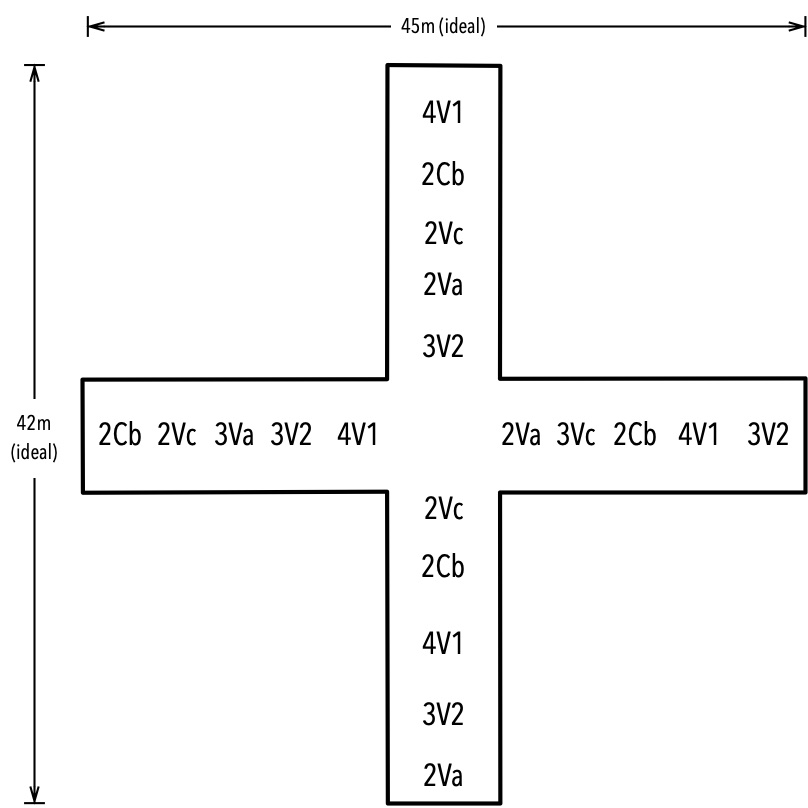

In und als wir, the 54-member string orchestra is arranged in the form of a cross with unconventional grouping orders of instruments, while audience members are seated between the arms of the cross or outside the structure (Fig. 3). This spatial arrangement is a key component of Spahlinger’s compositional strategy, designed to engender a number of auditory illusions in the localisation of sound.

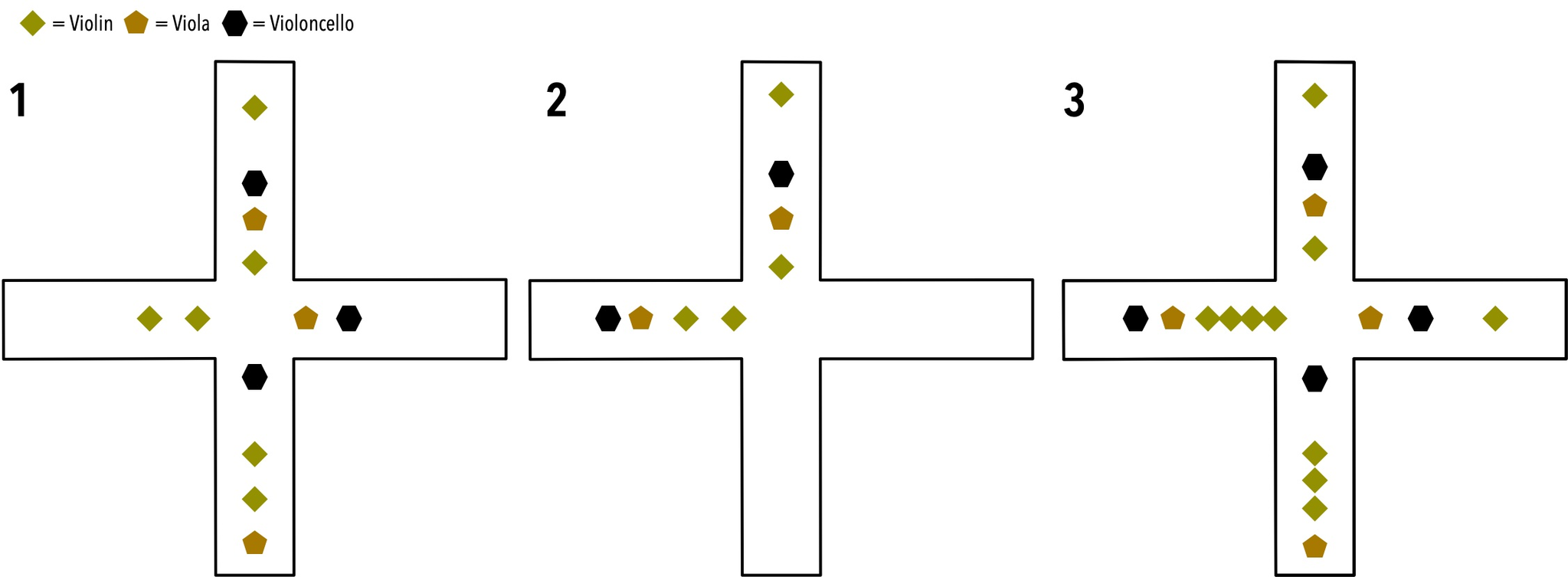

One such illusion occurs at bar 20 of the score, where three consecutive instances of damped harmonic pizzicati on pitch D5 are played in unison by different combinations of violin, viola and violoncello drawn from two or more arms of the cross (Spahlinger 1993). Owing to interaural differences, each of these unison doublings, produced by instruments placed at varying distances from listeners (Fig. 4), can be illusorily perceived as a single, unified sound emanating from a particular point in space, analogous to the spatial localisation effect produced in stereo recordings. Yet because the lower strings naturally produce longer decays, unexpected shifts in the perceived spatial origin of the sound become apparent as each attack decays (Spahlinger 2015).14

- This is despite of the practical impossibility of all instruments playing with absolute synchrony. The millisecond imprecision, large enough to produce interaural spatial cues but small enough to be absorbed within the larger strings’ decay, only yields a slightly different but equally interesting auditory trajectory than the idealised, totally synchronised version notated on the score. This productive indeterminacy, incidentally, exemplifies the difference between ideal notated concepts and sounds in actual reality, a mantra of Spahlinger.

What is particularly noteworthy is that these shifts are experienced differently across the hall: listeners in distinct positions perceive unique versions of spatial trajectories of sound, resulting in what might be called an indefinite multiplicity of circumscribed affordances.15 Furthermore, these variations occur at the sensory level—an unusual achievement—delimited not by listeners’ innate perceptual abilities but by their contingent physical locations within the concert hall (Fig. 5). In a genuinely democratic and non-hierarchical manner, Spahlinger challenges the idealised and privileged central “sweet spot” of concert listening (Spahlinger 2015, 146). Each listener encounters an idiosyncratic and equally vivid sensory experience, determined solely by their fixed place during the concert.

Naturally, it would be desirable that the conscious appreciation of this resultant intersubjective variation also forms part of the concert experience for listeners, as Spahlinger himself has hoped (Spahlinger 2015). To this end, the foregrounding strategy draws on the visual cues of the stage formation, the pronounced degree of salience of their newly encountered auditory phenomena and the cognitive dissonance caused by the perceptual incongruence between these visual and auditory cues. Nonetheless, as indicated by the series of downwards arrows in Fig. 5, this reflection on the visual-auditory incongruence is far from automatic. It demands an active sequence of engagement in redirecting attention away from the performance to fellow audience members, as well as exercising perspective taking to imagine others’ experiences. Consequently, among the various possible ways of engaging with the ongoing performance, progressively fewer listeners are likely to pursue this particular path and advance through each successive stage of inference. This trajectory marks a gradual shift away from the baseline circumscribed affordances towards the work’s preferred affordance.16

This difficulty of maintaining such a trajectory as circumscribed affordance highlights the composer’s central task of negotiating two forms of dissensus: between “what can be sensed” (through the creation of new aesthetic experiences) and “what can be sensed by whom” (by extending access to or privileging the previously overlooked groups). As with much of New Music, this piece challenges listeners to cultivate an open, exploratory and active mode of listening. In this respect, while the work’s higher-level preferred affordance—the new aesthetic experiences—favours those already adept at an exploratory attitude, the performative act of attending the concert and engaging with the piece—however disorienting—still serves as a training ground for other listeners to develop this capability. Hence, on a broader scale, the educational function of the work carries with it the ambition of extending the redistributive “what can be sensed by whom” beyond the immediate temporal bounds of the performance itself.

- A similar argument applies to the earlier discussion on the perception of spatial illusion, which is likewise not automatic. I thank the reviewer for raising this issue, as it opens a broader discussion about the circumscribed status of this perceptual experience. As noted in Spahlinger (2015), the capacity demanded here is not an exceptional one, but one routinely exercised in everyday life. Listeners are expected to perceive the effect as long as they can perceive spatial illusion while listening to stereo recordings. Nonetheless, not all listeners are equally prepared to notice and register this peculiarity. This challenge is compounded by the fact that the score contains only three notated instances of synchronised unison doublings, which are soon dispersed into scattered attacks. At the notated slow tempo, these three moments unquestionably suffice for attentive listeners, yet they may still feel too fleeting for those less experienced or less focused.

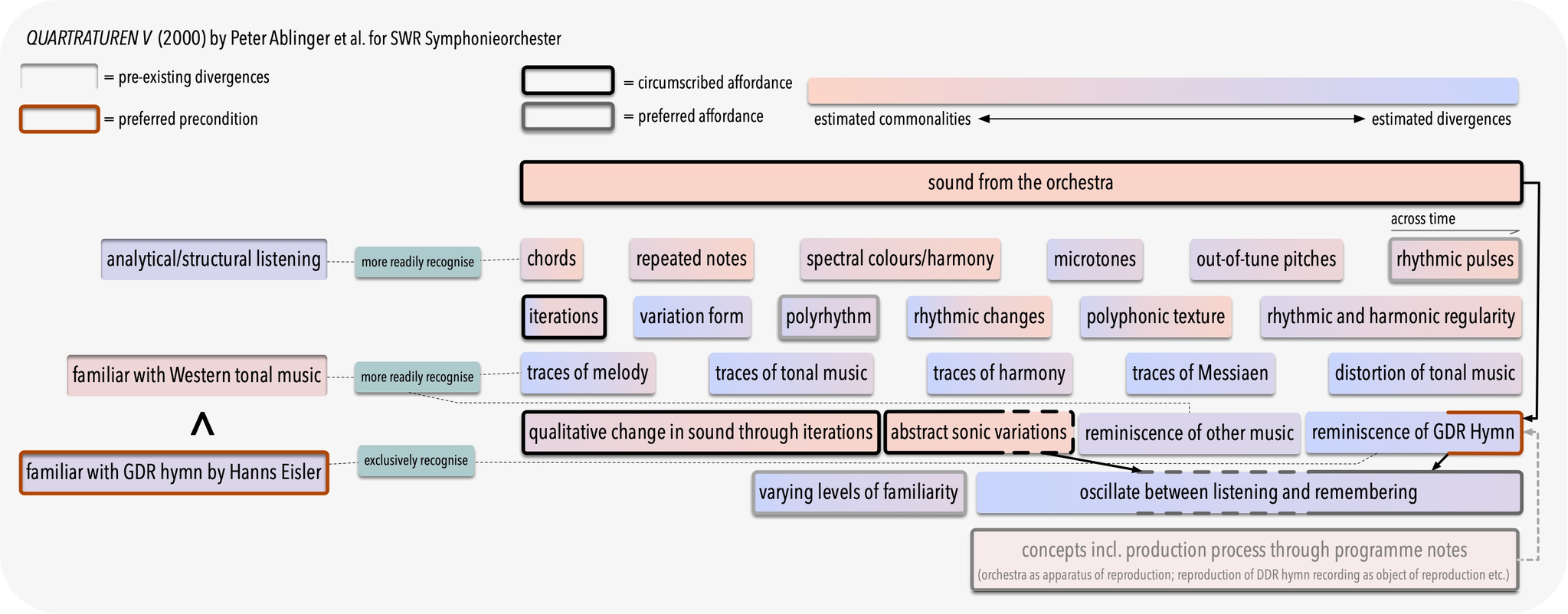

3.4. QUADRATUREN V (2000) by Peter Ablinger, Thomas Musil, Nader Mashayekhi and IEM Graz

The final example, QUADRATUREN V ("MUSIK"), is an orchestral transcription of ten iterations of an orchestral and choral recording excerpt of the anthem of German Democratic Republic, “Auferstanden aus Ruinen” by Hanns Eisler. Rather than a conventional transcription, ten iterations of the excerpt are each processed through a spectral filter of generally increasing temporal resolution, and then transcribed literally into orchestral parts.17 This results in the original recording not recognisable at first, but as the temporal resolution increases in uneven, non-linear steps, listeners may begin to form a faint impression or even recognise traces of the anthem (Ablinger 2006).

This work serves as a vehicle for examining several characteristic affordances and redistributions that conceptual works provide. First, the work consists of a conceptual idea and a specific process of execution that are not necessarily apparent in the performance itself: it conceives the orchestra as a reproductive apparatus, and treats the recorded anthem—already a reproduction—as the object of reproduction (ibid.). At its 2000 premiere at the Donaueschinger Musiktage, this information appeared in the festival’s single-volume programme, which was obtainable by attendees before the concert. As the choice of whether and when to read the programme notes was left to each listener, each person’s experience of the work was further differentiated in this respect.

Second, the choice of the musical quotation was deliberate. As Ablinger (2006) notes, the recording excerpt “must be well-known to be recalled”. Yet, in its premiere at an internationally renowned festival, the GDR anthem inevitably divided the audience into those familiar with it and those who were not, rendering any forms of its impression or recognition circumscribable only for the former. Moreover, the perceptual challenge in engaging with indistinct traces of the anthem further weakens its status as a circumscribed affordance, shifting it instead towards the realm of preferred affordances.18

Third, similar to Cage’s 4’33”, the work’s remaining circumscribed affordance is minimal. It primarily entails the sounds produced by the orchestra and their qualitative transformations over time, along with the ten-part formal structure whose long pauses unmistakably separated the segments. Any affordances arising from emergent or derived abstractions, like texture and rhythm, are peripheral to the work rather than circumscribed (Fig. 6). What also merits attention is the piece’s change in circumscribed/preferred affordances over time. For listeners familiar with the anthem but unaware of the piece’s concept, traces of the GDR anthem become perceivable only in the final iterations. By contrast, the opening is heard chiefly as abstract sonic structures devoid of explicit referents. At the ontological level, the work first presents itself for these listeners as an abstract non-referential sonic environment that foregrounds sensory experience, then gradually transforms into a hybrid form that also incorporates musical reminiscence and cultural allusion.19

- The spectral filter takes snapshots of the sonic spectrum of the recording excerpt at regular intervals. High temporal resolution corresponds to shorter snapshot intervals, resulting in higher fidelity to the original. The filter on the frequency axis, in contrast, remains fixed at 3/4-tone intervals (Ablinger 2006).

- In the German work description, Ablinger wrote: „Hoffentlich gibt es möglichst viele Zuhörer, die die Programmhefte erst nach der Aufführung studieren; ich würde nämlich zu gerne wissen, ob es auch nur eine einzige Person gibt, die das ‚Original‘ erkennt, heraushört, ohne zu wissen, was es zu hören gibt.“ (Ablinger, 2000; Hopefully, there will be many listeners who only study the programme notes after the performance; I would very much like to know if there is even a single person who recognises the ‘original,’ hears it without knowing what to listen for.)

- I am sitting in a room (1969) by Alvin Lucier is a renowned example that does the opposite, with the explicitly musical dimension emerging gradually over time for uninformed listeners.

As a result, QUADRATUREN V is marked by several forms of fragmentation in redistributing what can be sensed by whom. The reliance on programme notes introduces a redistributive dispersion in how listeners engage with the work’s conceptual idea, while a further split occurs with the unstable traces of the anthem, the engagement with which depends on the listeners’ strength of musical memory on the anthem, awareness of the concept, and level of attentiveness. Nonetheless, this piece also establishes an exclusive yet cohesive group, perceptually unifying those who have read the programme notes and are familiar with the anthem and, by extension, a socio-cultural community connected to the GDR’s cultural and political history.

As with Cage’s 4’33”, the work’s minimal circumscribed affordance shifts the responsibility of sense-making onto listeners. By negating the dominant mode of analytical listening that dissects sound into lower-level elements and cultivating the listening modes of recognition and association, the work may be seen as unsettling the conventional concert order. However, the absence of deliberate circumscription efforts on this may hinder its ability to challenge listeners’ habitual modes of reception effectively. Without knowledge of its conceptual basis, listeners may easily misinterpret the seemingly familiar sounds and resort to incompatible listening strategies. One online review, for instance, dismissed that it “quickly ran out of ideas” (MusicWeb International 2001), suggesting a conventional expectation of musical development through abstraction and manipulation of lower-level elements.

Ultimately, this lack of circumscription reflects an artistic stance not perfectly aligned with the performance frame and the cultural context of contemporary music concerts. Ablinger’s emphasis on the work being the entire process from conception to realisation (Ablinger 2006) reduces the significance of the immediate concert audience as the sole recipients of the piece. His Cagean openness to reception also reveals his aesthetic priority on interpretative multiplicity over prevention of misreading, arguably rendering those dismissive appraisals permissible.20 This misalignment likewise foregrounds his primary occupation with making “perception perceivable” in a situation-independent, universal sense (Ablinger 2024)—a form of dissensus oriented more towards “what can be sensed” (through the creation of new aesthetic experiences) than towards “what can be sensed by whom” (by extending access to or privileging the previously overlooked groups). In this regard, his practice associates more closely with the contemporary art culture, where the burden of explanatory and circumscribing labour is externalised to discursive framing and curatorial mediation rather than embedded within the performance.