5.1. D!V£R#!M&NT! (2024) for voice, flute, clarinet, violin and percussion

This piece aims to problematise the global dominance of the English language. It presents two sets of circumscribed affordances: one tailored for users of Yoruba, Cantonese and Hindi (henceforth native group)—native languages from three former British colonies—and another for English language users with limited exposure to these three languages (henceforth English group).26

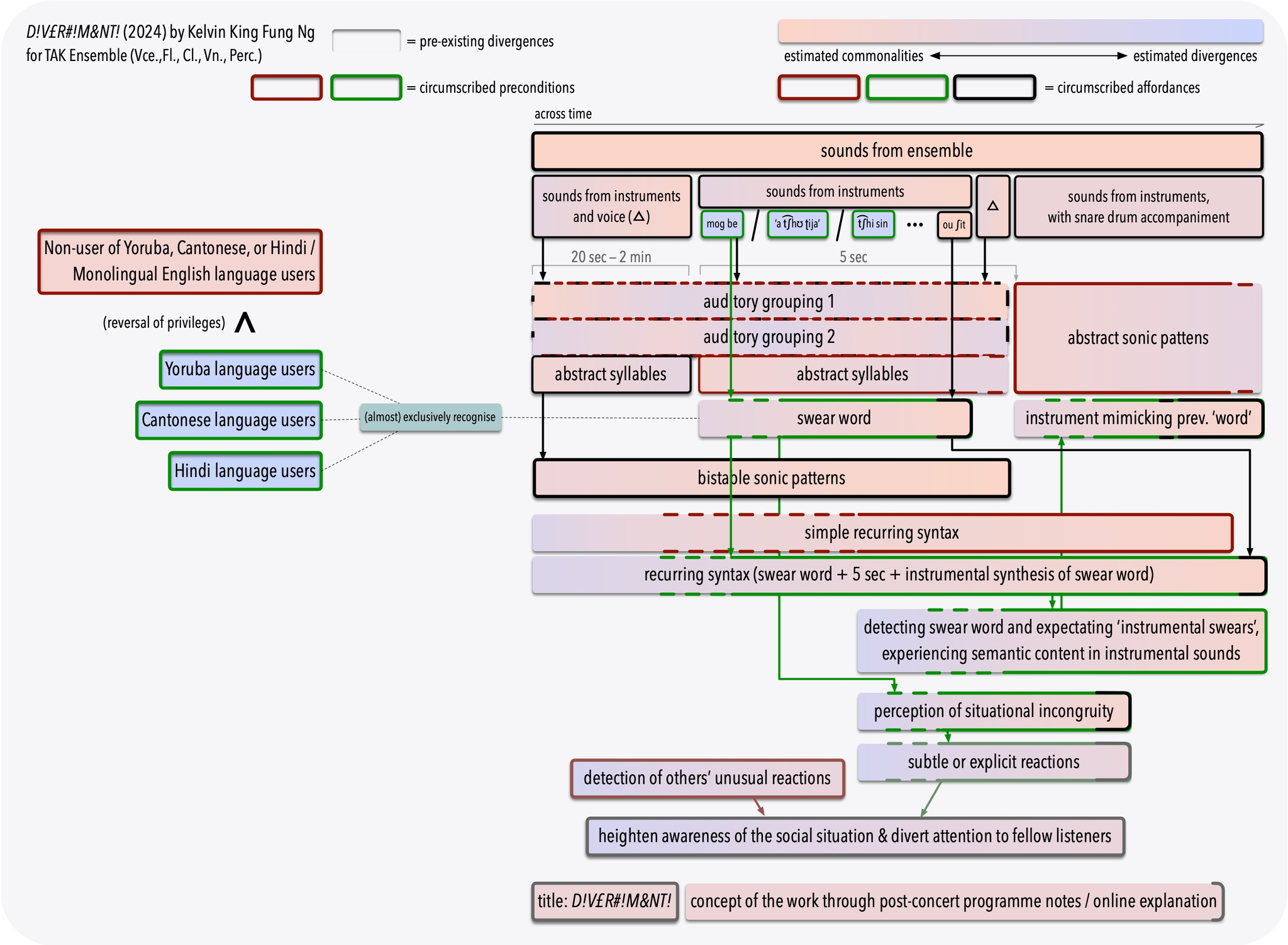

One method to simultaneously provide two sets of circumscribed affordances is through the dual identity of the ‘swear words’ in Yoruba, Cantonese and Hindi, with the languages cycling on each turn. Each time, the ‘swear word’ is first uttered by the vocalist and, five seconds later, imitated instrumentally by the ensemble. The vocalist’s ‘swear words’ are embedded in musical textures with shifting auditory-grouping cues, whereas their instrumental imitations are presented in isolation following a brief pause (Fig. 7).

Thus, the ‘swear words’ operate on both musical and semantic dimensions. Their vulgar semantic content is recognisable exclusively to the native group.27 The English group, on the contrary, perceive these ‘swear words’ solely as abstract vocal utterances and instrumental events integral to the layers of sonic transformation. Over the course of the work, this dimension of semantic recognition becomes increasingly polarised between the two groups, with the native group’s capacity for recognition exploited to the limit: vocal swears lifted from their original context are variously disguised within the musical textures; recognition persists even when they are rendered as instrumental emulations; and, eventually, they are cued nothing more than wire-brush motions on the snares. The audio example (Fig. 8) presents the ending of the sixth iteration of the work’s recurring syntax, featuring the vocal utterance of the Cantonese swear word “pok gai” and its instrumental emulation.28

This redistribution of what can be sensed by whom privileges the native group and produces specific forms of divergences and convergences between the two groups. The native group is offered a more nuanced and multi-layered experience marked by anticipatory directionality. Conversely, the English group, perceiving the piece mainly as a series of sonic transformations, may experience greater confusion with persistent pauses and interruptions, and can only infer the logic of the syntactical structure retrospectively—primarily through the only English swear word “oh shit” and its instrumental emulation at the very end.

Intersubjective differences are foregrounded through distinct mechanisms for each group. For the native group, they manifest primarily through the unexpected linguistic element of swear words and its incongruity with the context, drawing attention to the broader ground of social situation that anchors the performance frame (Brandt 2004, Oakley 2009). For the English group, they are highlighted mainly by detecting potential external sensory cues such as overt or subtle reactions from the native-group listeners.

5.2. Brief Version of Seoljanggu (2021–) for janggu drum-dance solo

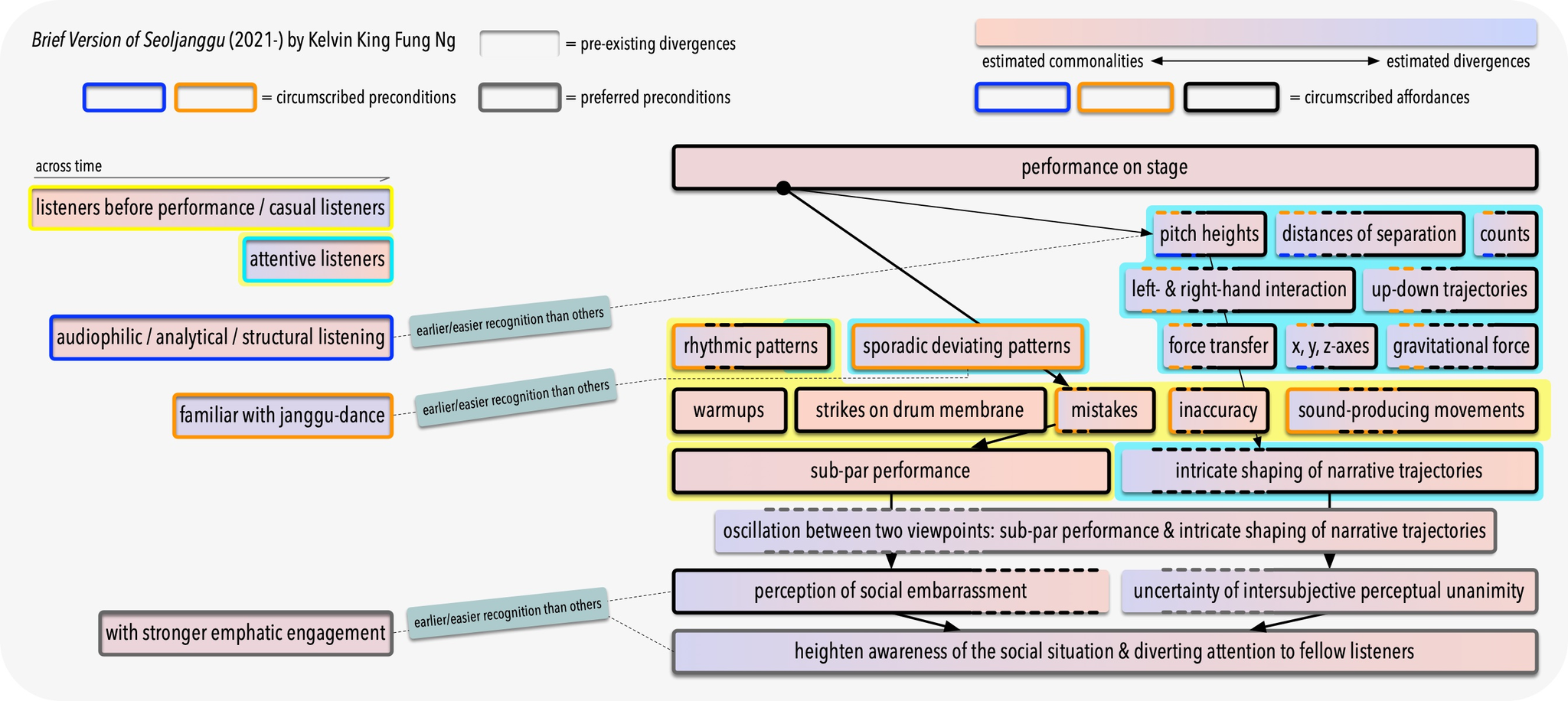

The redistributive aim of this piece is to engender an exceptionally exclusive communion within the concert audience, pursued and characterised in two manners: (1) by pitting listeners’ in-performance conditions against their pre-performance conditions, thereby creating a marked divergence between audience members and their past selves; and (2) by intensifying convergence among listeners from different cultural backgrounds as the piece unfolds, even for a performance practice less globally prevalent than Western instrumental music.

The first aim is approached by generating two concurrent sets of circumscribed affordances at the level of the work’s musical schema, tailored respectively to the listeners’ initial preconditions29 and to the conditions they gradually acquire in performance. On the surface, the performance disguises itself as a sub-par rendition of Seoljanggu, a traditional Korean drum-dance solo.30 Simultaneously, nearly every event admits an alternative reading as a component of an underlying coherent syntactic structure. These two sets of affordances are highlighted in yellow and cyan in Fig. 9 respectively. This is exemplified with one representative case (symbolised as the black dot in Fig. 9), in which a sequence of events can be perceived either as inadvertent drum-strike misses resulting from the performer’s anxiety, or as a deliberate strand of ascending pitches that leads to a cadential resolution (see video in Fig. 10; pay particular attention to instances where strikes fail to hit the drum membrane).31 With the piece's formal operations being intentionally ambiguous and what constitutes musical elements unclear at the outset, listeners individually attune to the second collection of circumscribed affordances over time.

- And those who are present but do not devote attention to the performance.

- This virtuosic solo is traditionally performed in Korean peasant harvest rites by the lead Janggu player and generally consists of four or five movements, each with a distinct form, meter, tempo, and rhythmic framework.

- The timestamps for the instances of misses on the left/darker side (gungpyeon) are 0:02 (two strokes), 0:10, 0:13–0:14 (two strokes), 0:19 and 0:24. In the same passage, there is also another strand of ascending pitches on the right or brighter side of the drum (yeolpyeon), with the timestamps at 0:06 (two strokes), 0:08 (two strokes), 0:12–0:14 (three strokes), 0:19–0:20 (two strokes). Both contribute to a general ascent in pitch for the whole passage.

Moreover, with respect to the second aim, listeners from different backgrounds acquire a more comprehensive knowledge of the syntax through separate routes. Individuals versed in the janggu practice would promptly identify the intermittent elements with dual identity by recognising their deviations from conventional technique and phrasing. Conversely, those acquainted with Western art music would more readily employ analytical listening to discern parametric changes in pitch heights and patterned recurrence, which then facilitates the recognition of other elements sharing similar syntactical roles.32

The redistributive outcome is thus characterised by a temporal convergence among listeners familiar with either of the two musical idioms, while over time they come to hold two contrasting readings: the illusory façade of a sub-par Seoljanggu performance and the intricately shaped syntactic structure.

The intrasubjective difference between the initial and acquired understanding of the performance’s nature is hence unmistakable when the two collections of affordances are compared. The perceived ontological uncertainty disrupting listeners’ normally shared agreement about what constitutes a work also redistributes their focus towards the performance context, including the presence and reactions of fellow attendees.33 Likewise, the perception of a seemingly embarrassing performance is readily apparent and particularly pronounced early in the piece. The resulting heightened public self-consciousness and priming of social reasoning partially divert attention to the social situation and to fellow audience members as co-assessors of the scene. Collectively, these dynamics engender a micro-sociality marked by internal unease and outward reticence.

- There is no claim that every audience member will experience an enhancement in intersubjective awareness; it is offered here as a preferred affordance. During my previous performances, dance-trained listeners have reported experiencing heightened emotional intensity due to this ontological ambiguity and their urge to seek verification from their colleagues.