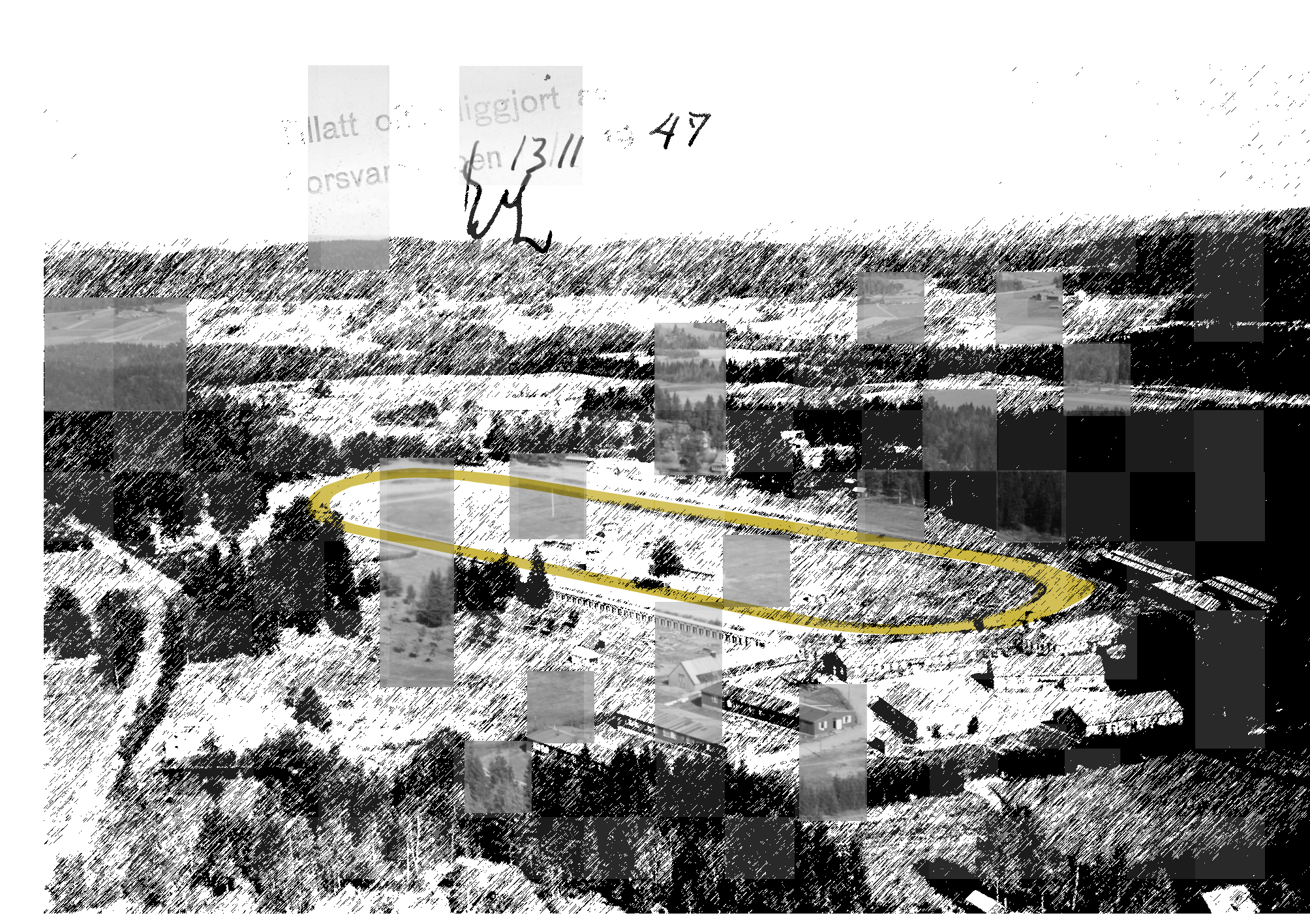

Above: The planned concentration camp at Momarken horse racing ground [5]. Below: Draw by number exercise. ©Hilde Kramer. Click on image to prepare for download on your computer.

Click on image above to hear the story

The Right Shade of Gray. If you want to read

the text without sound, please scroll right.

To see illustrations, scroll down.

20 minutes reading

Motif 1

A grayscale image is composed exclusively with a range of gray shades, holding a spectrum between the darkest black and blinding white. Someone who considers making a grayscale drawing must take certain decisions before the task begins. If a shade of gray looks nearly white, but still contains an element of darkness, how does one draw that?

Picture this: In the twilight, a man stands in front of an empty kerosene barrel in the back garden of a white wooden house. This is the residency of the local doctor in a small Norwegian town. Holding a matchbox in his left hand, he strikes a safety match along the side of it. The cardboard is damp and the first two matches break without igniting.

In the third attempt a sphere of whiteness explodes from the match. The next second it turns into a flickering flame, less brilliant than the moment before. His hand trembles a little as he carefully places the match next to a piece of paper inside the barrel. The yellow flame touches a typed document with hand-scribbled notes. Without a sound the flame moves quietly along the edge of the sheet, eating its way onto the paper, growing brighter by the moment. It appears as of its appetite is growing. The flame reaches a new document. Soon a feisty fire fills the entire kerosene barrel, rumbling like a satisfied belly. From a leather bag leaning against his leg, he picks up a new stack of papers and watches them sink into the fire burning wildly. Instantly the flames begin licking the surface of the thick pile of documents. Sheet after sheet, the papers curl and lean inwards towards the flames. Bold headlines and machine-typed letters glittering and quivering on the now velvet-black paper in the air, before they fade into brittle gray flakes of multiple shades in the air. Soon they burst and fall apart. The man reaches down and picks up a dry twig lying in the grass to shuffle the glowing content inside the barrel. Hundreds of glittering sparks fly up between flower buds in the apple trees. A few days later their petals too will burst open like shivering explosions of whiteness.

It is Tuesday morning, the 8th of May 1945.

Motif 2

In physics theory, black is not considered a colour, rather it is the complete absence of reflected light. Objects located in a room where light does not enter, appear to be black. Black objects exposed to sunlight heat up faster than light objects nearby.

I am watching a film recording, less than a minute's duration, dating from 1941 [ı]. It is one of the Nazi propaganda films shown on a weekly basis around the country's cinema halls during the Second World War. Usually there will be the voice of an energetic narrator who barks out a message intended to put the viewer in the right mood, whether the screen shows children frolicking in a Nazi summer camp or buzzing activity inside a strategic factory. But this particular clip, sandwiched between typical sound-based sequences of Nazi propaganda, is silent. Perhaps the film crew had forgotten to bring sound equipment for this assignment. Perhaps there were budget cuts. Perhaps there is no other reason, than a studio operator cutting some corners in production because of a deadline to get this feature shown as soon as possible in cinemas across the country. What we are watching is the Nazi-supporting Norwegian Legion's training camp outside Drammen. The squad of soldiers is preparing for departure, their first stop is a soldier camp next to a concentration camp with many thousand prisoners, outside the German city Celle. This is only a stop towards their final destination, the Eastern Front. Not only is sound missing from this film, but there is also strangely little contrast in the image. There are almost no dark shades, and no shadows are cast on the ground below the soldiers. Perhaps the light meter had not been accurately set for outdoor shooting in cloudy weather. Perhaps the developing fluid in the film laboratory was too old. Perhaps nobody cared.

The camera lens cuts these men in half-figures emerging in flat grayish light. One after the other they pose staring into the horizon with serious, almost gloomy features. Sometimes they glance briefly in the direction of the camera, but they never open their mouths. Their body language leaves the viewer with the impression that a moment earlier they may have heard something deeply upsetting before the camera started rolling. Maybe this is the moment they learn that they will not be wearing uniforms with Norwegian distinctions in battle. We know the many of the men found it deeply upsetting to have to fight on the Eastern front wearing German SS uniforms.

The fourth man in the film clip first looks directly at the camera lens with his body turned towards us, holding his arms clasped behind his back. The military distinction on his collar shows he is a doctor. His unusually dark eyes in an otherwise pale face stare firmly at us for a moment, then he looks away, as if he couldn’t tolerate another second of this contact.

The film can be found in the national film archive outside Oslo among the thousands upon thousands of documents from the Nazi period in Norway during the Second World War. It was filmed on 4th of August 1941. His first name happens to be August, too. This is the same man who some years later, on Liberation Day in 1945 will burn documents in the twilight of a smalltown garden.

Only a year and a half earlier, during the Nazi-German invasion, he was among the enrolled Norwegians at the fortress of Høytorp outside Mysen, fighting to stop the invasion of Norway in April 1940.

I admit that story in the garden, that opens this text, is my invention. Could it still be true?

Motive 3

Let the drawing begin. I have prepared a paper that has the exact dimensions 297 x 420 millimeters, which corresponds with the A3 format. It has a grid consisting of squares of 4 x 4 millimeters. Most of the squares have a number between one and eight, but a small amount of the squares is left blank. The blank squares should not be filled in. The other squares should be coloured, according to the number written inside the square. Number one represents the lightest shade of gray you can imagine, while black belongs to number eight. Many of the squares have almost the same shade, only tiny nuances separate them. This means you must stay sharp and focused to attentively check whether the shade of gray you leave on the sheet corresponds to the given number in the square, so the image will be truthful.

After the war, when the German occupying force was defeated, Norwegian collaborators and war criminals were arrested. Many were put on trial. Most of them had only been ordinary members of the Norwegian Nazi Party. 1,375 were acquitted, 5,500 were dismissed and 37,150 had their cases dropped based on the state of the evidence. Of those convicted, 30,002 were men and 16,083 were women, for a total of 46,085. 3,262 were convicted of financial treason.

When a jury decide on the question of whether a person is guilty or not, it is based on the material that the prosecutor and defense lawyer have presented during the trial, evidence that sheds light on the case from different sides. Has the accused person spoken the truth? Has the court been given access to all documents? Imagine how difficult it must have been to get an overview of a person’s activity during the war years. Telegram, telephone calls and postal correspondence were the means of communication on long distance.

The file dossier in the National Archives in Oslo on the activities of this man does not belong to the worst war criminals, in terms of law. For a while he led the Norwegian National Socialist youth organization. He was also a regional leader for the National Socialist Party in the area where he lived.

There were some minor episodes, such as shooting a hunting dog without the owner’s permission. On the darker side of the scale, is the fact that he volunteered for service as a doctor in the so-called Norwegian Legion at the Eastern Front fighting for the Germans. His final military rank is SS Senior Storm Leader, and he was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class for his service in May 1942.

Though his career is blooming during the war, there are signs of darkness in his own life. In 1941, during a drinking binge in a casino while training in the camp Fallingbostel outside Celle, he accidentally shoots a man. The wounded man is out of the hospital ward after a few days, since his injuries are not serious. The punishment for his negligent behavior is restricted movement outside the camp for six months. Not long after, his squad is transferred to Leningrad. During his time on the Eastern front, he keeps frequent correspondence with the infamous Minister of Justice in Quisling's government, Sverre Riisnæs. In one such letter, he requests the minister to pull some strings to grant him the position as district doctor. Another applicant is considered better qualified for the job, but the involvement of the Minister does the trick. He also proposes that confiscated radios belonging to members of the Norwegian resistance movement should be sent to soldiers on the Eastern front, since "the owners hardly will need these again."

There are weapons involved in a later event that occurs on New Year's Eve 1942 while he is stationed at Leningrad. In a fit of rage and drunkenness, he first attacks two Soviet women’s faces with a knife. The next target are the buttocks of a German SS-officer. Using the same knife, he carves off a piece of cloth from the man’s trousers. The reason behind his fury is, he finds New Year’s Eve party at the garrison ghastly boring. There should be fireworks, he shouts. In his efforts to make things jollier, he heads for ammunition storage. While searching for hand grenades, he is arrested, and sent to a prison cell. The next morning, he has no memory of the incident himself. But this crime is too serious to ignore. A case is built against him.

Heinrich Himmler personally intervenes some months later, resolving the original sentence given after this incident. Leader of SS and in charge of the police Friedrich Wilhelm Rediess, suggests that rather than sending him to prison, a three-week course in National Socialist racial ideology at Kongsvinger fortress in 1943 should be completed. Why is a Norwegian doctor with a history of alcohol abuse and violence of interest to high-ranking German leaders? No further connections are mentioned in the indictment, which was completed in the spring of 1948. He pleads to be released from custody. Imprisoned since May 1945, he worries for his family left with no income, he argues. His father is seriously ill. Pending the case coming up in court during spring of 1948, he is released from custody. In his correspondence with the court system, he projects an image of himself as a man of honor, someone’s whose promise can be trusted. Yet his next actions are precisely a contradiction to that image.

On March 25th, 1948, an old, leaky fishing boat built in 1889 arrives Bilbao at the Northern coast of the Iberian Peninsula [2]. On board is a group of Norwegian Nazi-collaborators awaiting conviction for thei involvement with the occupying German forces. The journey that started 22 days earlier has been perilous. The small boat is almost overturned by huge waves, the motor is most unreliable, yet they manage to continue to Lisbon in Portugal. No one knows exactly how he makes his way to Argentina. It takes time before he settles in, but within a year he is acting as district physician in the mountain region Salta, where there was a constant lack of medical staff.[3] His wife and children will eventually make the same journey, under less dramatic circumstances. Life in Argentina turns out to be less glorious than they had hoped for. His wife who has long had a drinking problem dies from alcoholic abuse. The three girls show signs of malnutrition when their father brings them back to Norway during the early sixties.

On their return to Norway, nobody turns up to arrest him. He doesn’t even have to pay any kind of compensation, which was usual for Norwegian citizens who had collaborated with the Nazi-Germans during the war. After the end of the war, there were some feverish weeks celebrating the Nazi capitulation. Those who had been on the wrong side were punished. In court settlements since 1945, 72 death sentences were announced, and 37 of these ended in execution. Little by little the national fury fizzled out; people were sick and tired of war. Even he receives no formal punishment after his return from Argentina, the small town has not forgotten his wartime behavior. Few patients turn up at his waiting room. After some years he moves to other districts to find work. He dies in August 1978.

Twelve years later a small, unremarkable book called The Last SS Camp is published [4]. The author, Arne Sandem, who worked as a local secondary school teacher, is also the publisher of the book. It goes unnoticed by historians and researchers for many years. The book treats the almost forgotten story of the planned extension from a small prisoner camp to a fullscale concentration camp outside the small town Mysen during the war. The most solid proof of such a camp, besides court documents after the war, is a construction drawing from 1944. Some barracks existed since 1940, but the concentration camp was never finished. Had the Nazi authorities succeeded with their plans, barracks for 3000 - to 5000 prisoners would be erected. The drawing also shows a hospital, several washing rooms, and a crematorium. A surreal element in this drawing, is the outline of the local horse racing ground that existed at this place, where business is thriving to this day. Since Norway did not have any full-scale concentration camps during the war, how has the plan for such a camp escaped the public memory?

On page 45 of Sandem’s book there is an organization chart showing the most prominent positions of those who appointed responsibility for the concentration camp. The name Hans Aumeier might ring a bell for some. He was an Austrian Sturmbannfuhrer that had worked in many concentration camps. He was convicted for the particularly cruel crimes he committed towards prisoners in Auschwitz. In the book, Sandem describes in detail every person in the organization chart, exept for one, the camp physician. The name found in the chart is A. Inger. No Nazi-German doctor with a resembling name is found in the Bundesarchiw in Germany. However, in this small town, the district physician installed by the Nazi system, had also served on the Eastern front. His name was August Ingier. By the time Sandem published his book, Ingier had been long dead. Perhaps leaving him out of the story was an act of mercy to the family.

Does it make sense to talk about truthfulness in connection with grayscale images? The human eye sees the world in full colours. A grayscale image is a translation, a modification where information has been disclosed from the representation.

With a big image, the task becomes quite complicated. How do you keep track of the nuances, without getting lost in options? Suddenly the brightest white appears to be smudged. How dark was the gray next to black, again? Just as the mosaic of gray shades makes little sense if we stand too close to the image, a true image of this man raises from the mosaic of information if we step back to see the full image. Through the distance of eighty years, we can start to see which shades of gray would be most fitting.

REFERENCES

[1] Den norske legion, Filmavisen 4.august 1941 © NRK https://tv.nrk.no/serie/filmavisen/1941/FMAA41000141/avspiller

[2] Thon, J.I. (2023) Den norske SS-legen. Aftenposten https://www.aftenposten.no/historie/i/MomR0R/den-norske-ss-lege

[3] Furuseth. A. K. (2014) Norske nazister på flukt : jakten på et nytt hjemland i Argentina p.85-87. https://www.nb.no/items/68cf625b43e27cfac22f7b9e2aef2d79?page=87&searchText=Furuseth,%20Anne%20Kristin

[4] Sandem, A. (1990) Den siste SS-leiren

[5] Construction plan drawn by an architect who was incarcerated at Grini prisoner camp 1944. It shows the planned concentration camp at Momarken. Arkivverket: RAFA-3915. Forsvaret, Forsvarets overkommando II CI-Questionaires.