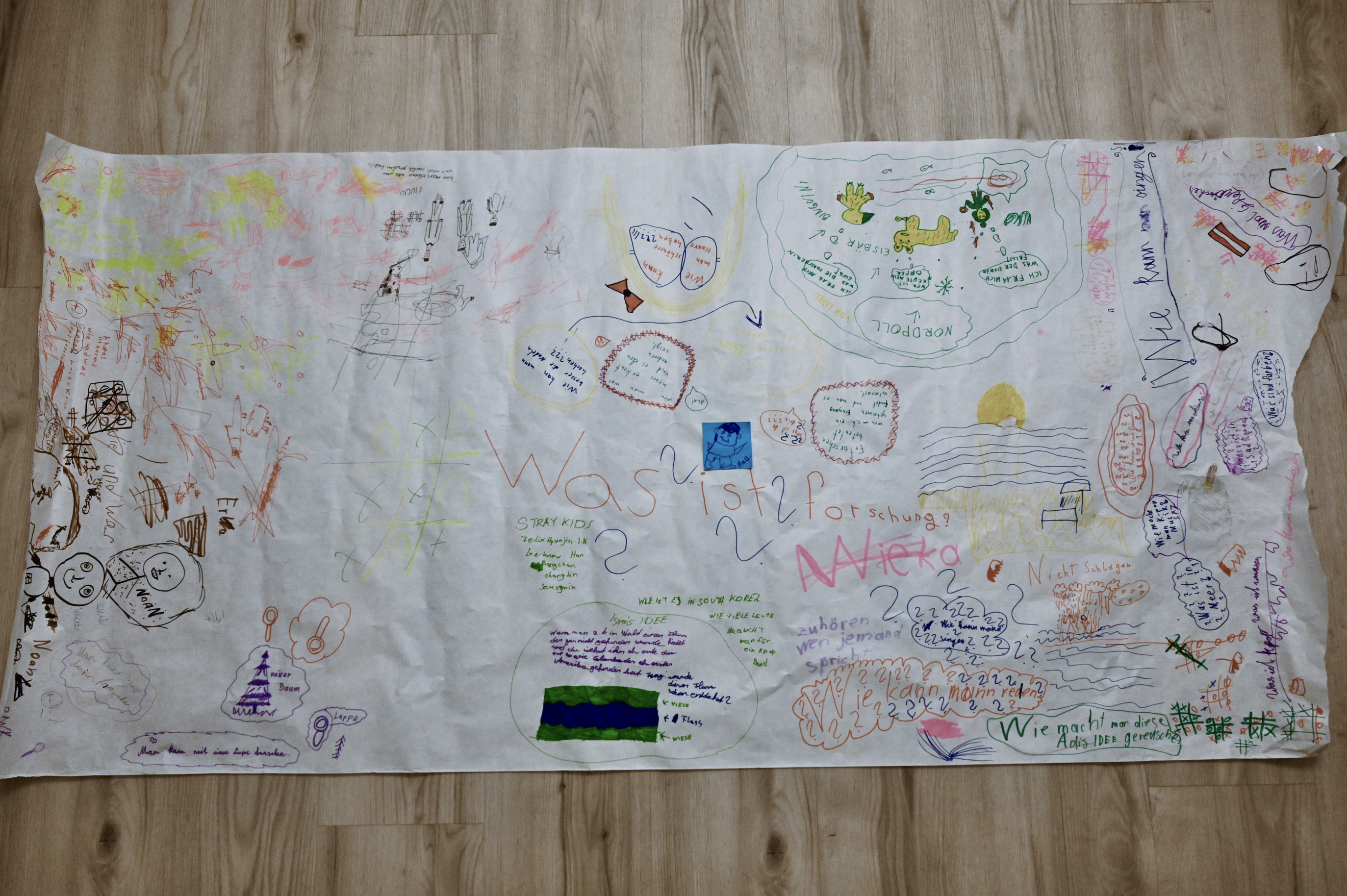

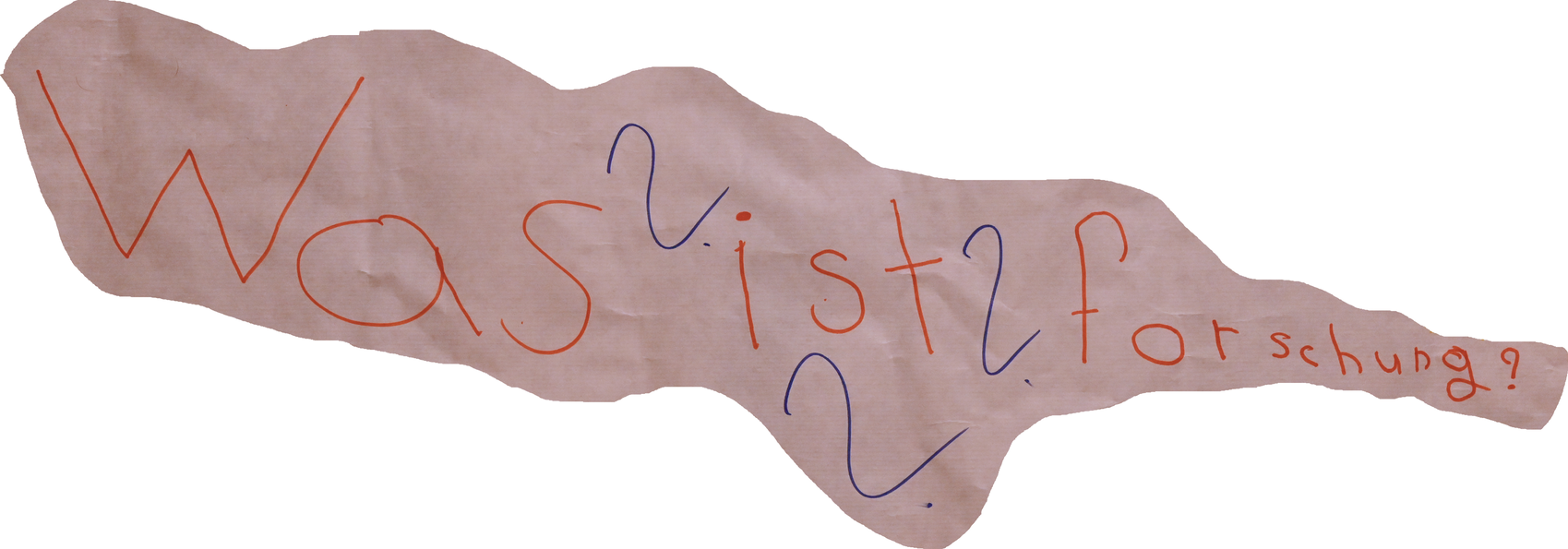

In one of our research sessions, we explored the concept of research on a collaborative mural asking ourselves and each other: What does it mean to investigate something? How do we ask questions?

There was no single right answer. Instead, we practiced shared thinking, an open exchange where drawing, writing, and speaking became ways of exploring what “research” might mean to each of us. Through this, we treated inquiry itself as a creative act, shaped by listening, imagination, and difference.

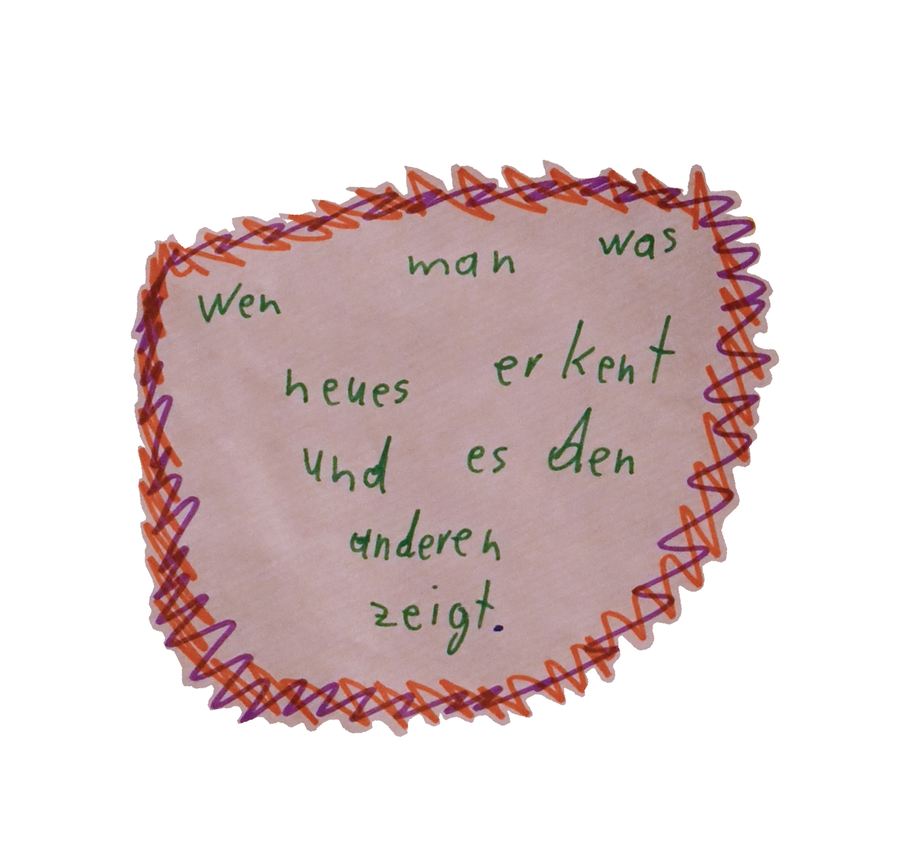

“Wenn man was Neues erkennt und das den anderen zeigt.” (“When you recognize something new and show it to others.”)

This statement presents research as a process of recognition and communication. It suggests that research is not only about discovering new things but also about making them visible to others. The phrase “etwas erkennen” (to recognize something) implies an active process: one must observe, notice, or realize something that was previously unknown or unnoticed.

Equally important is the second part of the statement: “und das den anderen zeigt”. Here, research is framed as a social activity; knowledge is not complete until it is shared. This reflects a participatory understanding of research, where discovery gains value through communication and exchange.

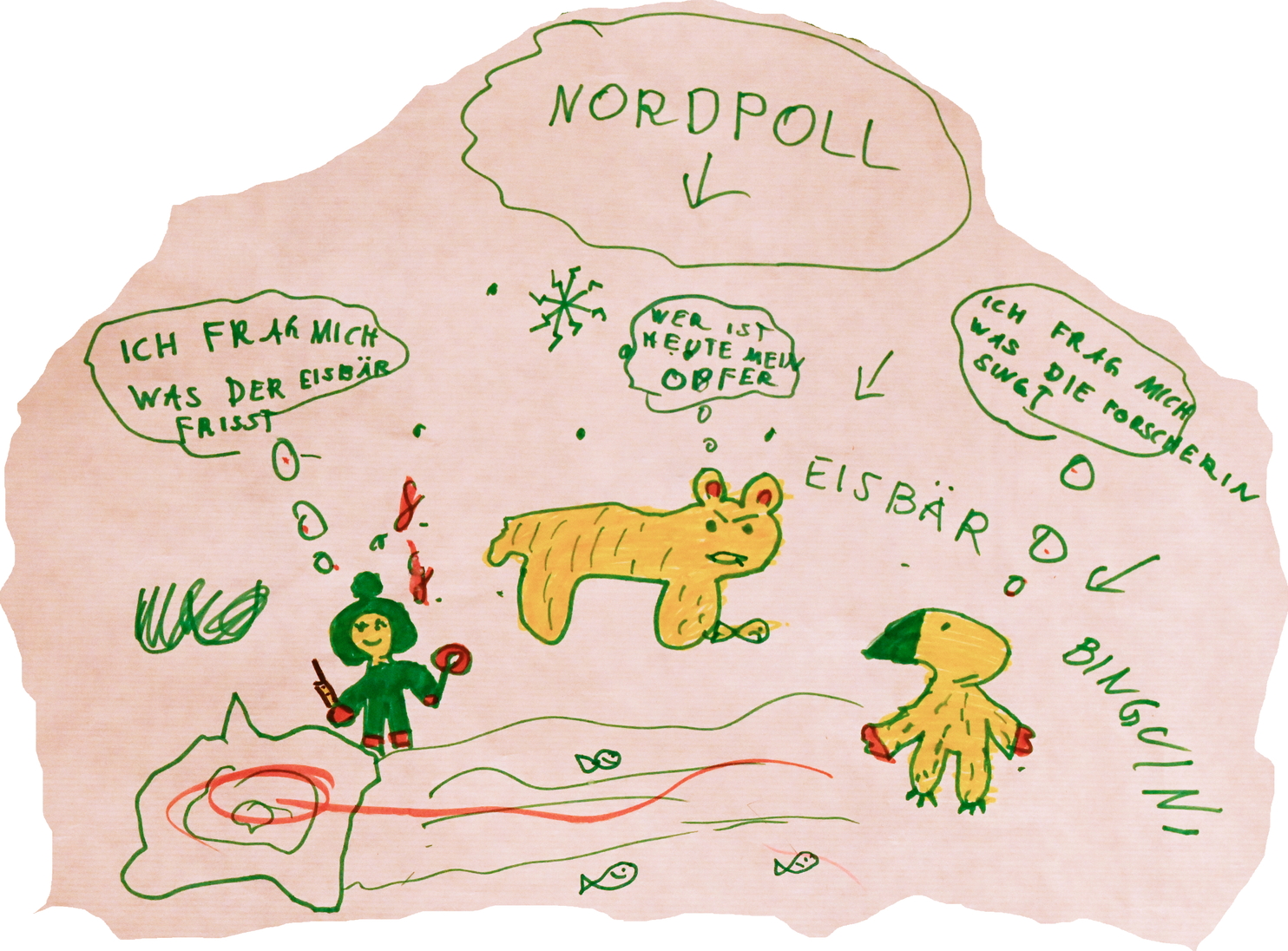

One researcher responded by drawing a scene of the North Pole, where three characters—a human researcher, a penguin, and a polar bear—each engage in their own inquiry.

At first glance, the drawing humorously subverts expectations, but on closer examination, it reveals a specifc understanding of knowledge systems and relational inquiry. Each character is engaged in research, but their questions emerge from different perspectives, motivations, and realities:

The human researcher thinks: “I ask myself what the polar bear eats.”

This is a classic scientific research question, rooted in an external observer’s curiosity about the animal world.

The penguin thinks: “I ask myself what the researcher sings.”

Here, a surprising shift in perspective happens, instead of observing another animal, the penguin researches the human through sound, emphasizing a knowledge system that values listening, expression, and embodied experience rather than external classification.

The polar bear thinks: “Who will be my victim today?”

This is a humorous but stark reminder of power, survival, and agency. Here, the bear does not research in an academic sense but engages in an instinct-driven inquiry of its own, one where survival dictates its line of questioning.

This drawing moves beyond traditional hierarchies of knowledge (human studying animal) to suggest a multi-directional research process, where inquiry is shaped by one’s position, needs, and environment. The scientific knowledge system is represented by the researcher’s question. The sensory, artistic, and embodied knowledge system is reflected in the penguin’s curiosity about song. The instinctive, survival-driven knowledge system emerges in the polar bear’s internal world.

Some follow-up questions that might be read out of this drawing could be: Who gets to ask the questions, and from which position?

Together, these reflections reveal how research, for us, unfolded as both social and exploratory. In the mural, it was not a fixed method but a living, collective process: a shared practice of thinking, sensing, and imagining alongside one another.

“Erforschen bedeutet, wenn man z. B. einen geheimen Eingang findet und man es untersucht.” (“Research means, for example, when you find a secret entrance and investigate it.”)

This statement frames research as an exploratory process: one that involves discovery, movement, and investigation. Unlike the first definition, which emphasizes recognizing and sharing knowledge, this perspective suggests that research requires actively finding a hidden path and then engaging with it.

The phrase „einen geheimen Eingang findet“ (“finding a secret entrance”) evokes a sense of adventure, positioning research as something dynamic and spatial rather than purely observational. It implies that knowledge is not always immediately visible, it must be searched for, uncovered, and entered.

The second part of the statement, „und man es untersucht“ (“and investigate it”) emphasizes that discovery alone is not enough. Research is not just about stumbling upon something unknown; it requires engagement, curiosity, and deeper inquiry. This perspective aligns with an embodied and experience-driven approach to research, where knowing emerges through interaction rather than passive observation.