The tuning of small kanteles varies with their structure and the music being played.

Most small kanteles currently made in Finland are designed for D tuning, with the tonic (string 1) tuned to D4.

In the past, small kanteles were tuned in many different ways, without standardization. Since players often built their own instruments, the size and structure depended on the wood chosen, which led to differences in string length and number (— view images of museum kanteles at SKVR & KANTELE). Archival sources show that kanteles were usually played alone, so tuning was adjusted to create the most resonant and pleasing sound for each player.

I apply this idea with my own small kanteles and often avoid forcing them into standardized tuning. Yet, to keep the learning process clear, the steel‑stringed kanteles in the videos are tuned to the common modern standard: D (A = 440 Hz).

In addition to steel‑stringed kanteles, the instructional videos feature two replicas of 19th‑century hollow kanteles. The five‑string instrument represents a northern model, hollowed from below with an open bottom, and it has bronze strings. The larger twelve‑string instrument is a southern model, hollowed from above and fitted with a separate cover plate, with strings of brass wire. Both instruments are tuned lower than steel‑stringed kanteles.

In the instructions, strings are numbered instead of named by pitch. This frees the player from fixed tuning levels or scales, since the numbering remains unchanged. String 1 is the tonic, string 2 the next shorter string (the second degree), and so forth. In kanteles with more than five strings, the scale extends downward; in today’s 10–15‑string instruments, strings below 1 usually correspond to the 7th, 6th, and 5th degrees.

On a five-string kantele, the longest string is typically tuned to the tonic of the scale. The strings are numbered in descending length: 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5.

The traditional tuning sequence is:

- 1–5 (fifth)

- 5–2 (fourth)

- 1–4 (fourth)

- 5–3–1 (triad chord with the chosen third)

You can produce harmonics by lightly touching the string at its midpoint (or one‑third, one‑fourth, etc.) with the index finger of your left hand. The more precisely the touch coincides with the node of the partial, the clearer the harmonic will sound. If needed, refine the touch by slightly tilting your finger, so that it contacts a narrower section of the string.

Pluck the string firmly with a right‑hand finger, and a harmonic should be heard. If the left‑hand finger does not press too hard and is released immediately after touching the node, the partial will sound clearer and sustain longer.

Checking the fifth and the fourth intervals with harmonics:

- The harmonic from one‑third of string 1 should match the harmonic from the midpoint of string 5.

- The harmonic from one‑third of string 5 should match the harmonic from one‑fourth of string 2.

- The harmonic from one‑fourth of string 1 should match the harmonic from one‑third of string 4.

To tune a five‑string kantele to the major scale, harmonics can also be used on the third string. The harmonic produced at one‑fifth of string 1 should coincide with the harmonic at one‑fourth of string 3.

At this stage, it is important to note that the intervals checked with harmonics are (almost) natural and differ from the equal‑temperament values shown by the tuning meter. For string 3 the difference is considerable: tuning it by harmonics yields a natural major third, about 14 cents lower than the equal‑tempered major third indicated by the meter. (Tuning meters measure deviations from equal temperament in cents, where 1 cent = 1/1200 of an octave.) These differences significantly affect the kantele’s soundscape and resonance.

If you want the kantele tuned to a minor scale, the third string should be set higher than the value indicated by the tuning meter: a natural minor third is about 16 cents above the equal‑tempered one. The compatibility of the partials can be checked with harmonics by touching string 3 at one‑fifth and string 5 at one‑fourth of their lengths. However, producing such high partials on the short fifth string is difficult — depending, of course, on the size of the kantele.

To ears accustomed to the equal‑tempered scale, natural thirds may already sound like “something in between.” In practice, however, even greater deviations — pitch levels that differ from natural thirds — are classified as neutral thirds.

If natural thirds sound unfamiliar, try tuning the major third about 5–10 cents lower than the equal‑tempered pitch, and the minor third about 5–10 cents higher, using a tuning meter. Even such small adjustments will noticeably affect the overall sound.

Despite its limited number of notes, a five‑string kantele cannot be tuned to a completely natural scale. According to the model presented above, the fifth, the fourths, and the third between strings 1 and 3 are naturally pure. However, the third between strings 2 and 4 is noticeably narrower than the natural minor third.

As noted earlier, there is no single “correct” tuning for the kantele; rather, it is always a balance of compromises.

When string 2 is lowered by a semitone relative to the minor scale, the interval between strings 2 and 4 becomes a major third. In this case, the scale resembles the first five notes of the so‑called Phrygian mode.

If the 4th string is raised from the major scale, the 2–4 third expands into a major third again, and the resulting scale corresponds to the first five notes of the Lydian mode.

You can explore neutral thirds by tuning string 3 a little below the natural major third or a little above the natural minor third.

Feel free to experiment with different tunings and enjoy the musical possibilities they open up.

Because of how the strings are attached, traditional kanteles produce a beating sound. This makes exact tuning difficult, but it also helps smooth out tuning problems. In brass‑stringed kanteles, where the tension is lower than in steel‑stringed ones, the beating is an even stronger part of the sound.

In addition, both the pitch and its perception are influenced by playing technique: which finger is used, where on the string the sound is produced, and with what strength.

All of this means that there is no single "correct" tuning for the kantele; rather, the tuning that best suits each instrument, moment, and piece of music must always be sought afresh. Like the sound field, tuning encompasses multiple ways of hearing, each valid in its own right. Some compromises are inevitable, and the musician must choose the tuning that best fits the situation. If the aim is to improvise your inner power, then the right tuning is simply the one that sounds right to you.

As described in the prologue, in music played with the traditional plucking technique, the sound field carries greater significance than the individual notes. Therefore, when tuning the instrument, one should listen to the overall resonance created by the notes rather than focusing solely on the pitch of single strings.

If the string lengths of the kantele are relatively short, fine tuning becomes difficult: even a small adjustment of the tuning peg produces a surprisingly large change in pitch. On kanteles with metal pegs, an L‑key — a long‑handled tuning tool — makes tuning easier. If you hold it at the end of the shaft, your larger hand movement becomes a smaller adjustment at the peg.

You can use the accompanying videos just as you use the examples on the playing instructions page. They show possible ways to try out and discover tunings that work for you.

As in the Karelian tradition, tuning is guided by the sound of fifths, fourths, and octaves rather than step‑by‑step adjustment. This approach helps achieve the desired resonance and sound field through the traditional playing technique.

The tuning method that relies on listening to harmonic relationships also naturally brings out the scales documented from Karelian kantele players. These practices predate the establishment of the modern major–minor system. Some of the scales resemble those theorized in European monasteries and churches during the Middle Ages — the so‑called modes — which themselves were based on scale models already in use centuries earlier.

Karelian kantele scales share with runosong culture a special trait: the flexibility of thirds. Runosingers could shift the pitch of the third and sixth degrees of the scale (and at times the seventh degree below the tonic) between major, minor, or a neutral position in between them. Similarly, kantele players adjusted the tuning of the corresponding strings (3, 6, and 7) to produce high (major), low (minor), or neutral thirds.

In larger kanteles, the 7th note was often not tuned on the upper strings, but it was tuned below string 1. If the instrument had enough strings, the longest one could be tuned to the lower octave of the tonic, sometimes doubled on two strings for resonance. Sometimes the lower octave of the second note was also added. With these low notes, string 1 was placed on the fifth or sixth longest string.

As a result, scales differed in many ways between kanteles, players, and contexts, thus supporting personal music‑making rooted in the moment.

If you tune the kantele step by step with a tuning meter, you will get a good enough result to play the exercises. But if you want to go deeper into the traditional sound world, you should try interval tuning and listen to the harmony of the notes.

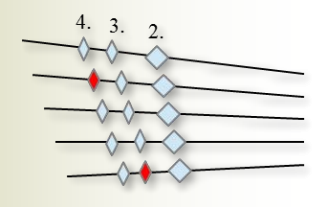

In small kanteles with more than five strings, the most common tuning in current Finnish models places the tonic on the fourth longest string. From there, the scale extends both upward and downward. For example, in an 11-string kantele, the string numbers counted from the longest are: 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 (the octave of the string 1). Thus, the three longest strings lie below the fundamental note, and sometimes a mark is added next to these string numbers to indicate the lower octave.

In the tuning sequences recorded by Karelian kantele players, tuning is primarily carried out using fifths and octaves. On an 11‑string kantele, the tuning sequence of the major scale could proceed as follows:

- String 1 (tonic) tuned to the desired pitch

- Fifth: 1 → 5

- Octave: 5 → (low) 5

- Fifth: (low) 5 → 2

- Fifth: 2 → 6

- Octave: 6 → (low) 6

- Fifth: (low) 6 → 3

- Fifth: 3 → 7

- Octave: 7 → (low) 7

- Octave: 1 → 8

- Fifth: 8 → 4

- Fifth: the harmonic at one‑third of the lower string should match the harmonic at the midpoint of the higher string

- Octave: the harmonic at the midpoint of the lower string should match the open higher string