Standards and Indeterminacy

In much artistic work, the output of the work is intended to be experienced first-hand. Interpretation is a part of an individual, unspoken, perceptual process. The process by which visitors ascribe meaning to a work is part of the situation involving a perceiver and the embodied artwork itself. To attempt a full linguistic description of an artistic research work will involve a necessary incompleteness. This points to a key difference between artistic research and research in most other fields. In artistic work, research questions and outputs are materialised through the working process and/or embodied in art pieces themselves. There is no requirement for artwork to be expressed other than in this embodied and embedded form. In contexts where language is required as a means of explaining or justifying research this results in interdisciplinary dilemmas. Yet, the facticity of artworks as things in themselves, tangible processes enacted in a shared social and perceptual space, evidences a greater objectivity than research output as words and data alone. This fundamental objectivity of the artwork as object, site, or process does not limit the work in the manner of the Wittgenstein quotation previously discussed. We do not need to ‘pass over’ the artistic phenomenon ‘in silence’. Instead, the work becomes a useful node in a network of corollaries that may be drawn around it.

The pieces in Norths materialise their research questions and propose their answers in objective form, as objects and processes in the world. While philosophical questions may be asked in philosophically written language, in artistic practice they emerge ontologically. These are process-objects, revealed through inter/ra-action and encounter. For the aesthetic exchange to take place, the requirement is that the questioning observer be a committed participant within the world proposed. To connect rather than attempt to isolate the observer from the experimental process exemplifies another strong divergence in methodology between artistic research and many other fields.

The Norths-works exhibit a hybrid ontology in the manner just discussed. They are process-objects, taking up space and making sound. Yet they are also open to the world, taking a part of their being from data, information gathered by the works themselves or collected by them using the internet. Finally, in yet another way their being depends on visitors’ participatory response to them, and in this way their objectivity is subjective. Data and its relationship to ‘truth’ or ‘reality’ are revealed in Norths to be less fixed than how they are often presented. In examining this corollary of Norths, this section reveals its basis to be in a common misunderstanding and misuse of the notion of standards in general. Following from this, the undervaluing of contingency and noise, aspects of the world foregrounded by several Norths-works, is critiqued. A final section proposes a phenomenological perspective viewed through Norths, akin to contemporary work in mathematics and measurement.

A central aspect of the problem is revealed in consideration of a common standard of measurement, the metre. The metre offers certainty in measurement of distance through reference to a standard metre. This, the Mètre Étalon, originated in post-revolutionary France, and has been updated several times. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, copies of the standard metre were used as stand-ins for the original. These objects can be found in museums and remain embedded in the architecture of the time, particularly in public squares where markets were conducted. These objects offered their users symbolic certainty as to the measure of a given span, in that, through reference to themselves, they in turn refer to the original. The certainty provided by these objects is symbolic for at least two reasons.

Are these objects copies of the original standard or standards themselves? As copies, these new metres would, by nature, be imperfect renderings of the original. Perhaps for practical purpose they are ‘close enough to the original’. However, this highlights the problem rather than resolving it: what is it that these metres are close enough to? Is it another approximation of a distance, or instead an abstract idea by which ‘metre’ is designated? If, instead of a representation of the standard metre, the newly produced metres approximate an idea, then, as in the objectification of any geometric idea, the physical rendering will be imperfect. These are copies without originals, which Baudrillard terms ‘simulacra’ (Baudrillard 1994). The question ‘close enough for what?’ reveals a fundamental incompleteness and groundlessness to the establishment of a standard.

A second issue arises in that any application of the standard metre would have recourse to a subjective comparison. Were the metre a copy (or simulacra) embedded in the wall of a public building, performing a measurement in relation to this with any accuracy would be problematic if not comic. This highlights the subjectivity latent within the objectivity that the measurement purports the assurance of.

An argument was established in the preceding section for applying linguistic standards to truth claims. This can now be extended to objective standards in claims regarding measurement. On the one hand, subjectivity in the handling and measurement of data is inseparable from the objectivity of the data produced. On the other, where standards are applied, scale necessarily limits the precision of a referential object. This becomes still more problematic when the object of initial comparison is an idea rather than a physical object.

These issues are raised not to point to problems with standards or measurement in practice as much as how they are used to justify truth-claims outside of the order of magnitude and frames of reference being measured. The common fallacy of correlation taken as an implication of causation is a common example of the misuse of measurement and standards. The over-reliance on data as truth without examining the perspective from which that data has been gathered is another. Norths aims to situate circumstances in which visitors become aware that they themselves are data collectors and that what they collect is highly dependent on the perspective that they adopt. This is a timely concern, as data treated as a stand-in for empirical experience is being programmed into our digital devices in daily use. From the plotting of navigational routes to the choice of musical playlists, preference is given to data collected from a user or other users over an individual’s own decision-making. That this is becoming a default approach within devices and apps points to a form of the misuse of data and measurement highlighted here. Where universality or inference outside of a particular instance of measurement is claimed for data, the inherent groundlessness and incompleteness of objective measurement standards reveal indeterminacies in any truth claims.

The situations discussed so far point to a persistent ideology of separation between subjects and objects, people and environments. By contrast, Alva Noë a contemporary philosopher and psychologist, points to an essential relationality between them (Noë 2005). In Action in Perception, Noë argues that the functioning of human perception provides a fundamental grounding for the type of embedded/embodied ecological approaches previously discussed in relation to the work of Merleau-Ponty. Relationality, for Noë, reveals objectivity through bodily acts of physical negotiation, as described by Merleau-Ponty in Phenomenology of Perception (Merleau-Ponty 2012). Technology and data cannot be used to bypass relationality en route to knowledge of reality. Instead, as argued by polymath Michael Polanyi, such knowledge is fundamentally based on ‘know-how’ acquired through embodied interaction rather than rational recourse to data (Polanyi 1966). The data one relies on in navigating the environment is empirical or the embodied knowledge of previous empirical experience. Where data is retrieved for use it too becomes part of the environmental relationality, rather than remaining separate from it.

‘Standards’ are templates, grounded in an imperfect material approximation of an ideal that is only subjectively verifiable. They are great for daily tasks and for facilitating communication, but to mistake the standard for reality is to mistake the finger that points to the moon for the moon itself, as the ancient Surangama Sutra points out (Surangama 2025). As we move towards a daily life that is increasingly saturated with data-dependent instruments, it is useful to know what assumptions the apparatuses that we surround ourselves with are making, and what information they choose to disregard on our behalf. As poet Robert Frost writes in 'Mending Wall' from 1914 (Frost 2025):

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out

The next section discusses how and why noise, that which is often ‘walled out’ where data is concerned, is given a place of prominence in Norths.

Revealing Deviations: Symbolic Certainty Versus Noise

Where most applications of sonification seek to remove or de-emphasise indeterminacy, in several Norths-works it is teased out and foregrounded. In developing Norths, artefacts often accompany insights, revealing aspects of how data is structured or communicated between networked systems. This is the case in several of the individual works and is discussed specifically in terms of Brraaap and Bird on a Wires. To listen more deeply to noise can be like following a trail of dropped breadcrumbs, or Ariadne’s thread, to a clearing from which a wider perspective on one’s technologically mediated operative reality can be attained (Battistini 2002).

Philosopher Martin Heidegger refers to a situation in which the hidden structural relationship between a technology and a user is revealed in the malfunction of equipment. This is akin to the way errors, artefacts, and noise offer a perspective on data in Norths. For Heidegger, the breakdown of equipment signifies a transition of states of being for that equipment, from ‘ready-to-hand’ to ‘present-at-hand’ modes of being for an object (Heidegger 1978). Roughly put, the smoothly functioning ‘ready-to-hand’ tool (or data) is taken for granted. When this is functioning as intended it ‘recedes’ (Harman 2018). By contrast, unintended by-products (noise, artefacts) or outright failure of the apparatus (error) render its presence available to our awareness and the technology becomes ‘present-at-hand’. In Norths, the shift in perspective that accompanies this transition has become a sought-after theme rather than a residual artefact. In Norths, we listen out for noise and artefacts, learning from this about the structure of the data and the communication networks involved.

Procedures that use noise to reveal environmental features are more common than one might assume. Below I will illustrate how noise can be used to reveal data about place on the human scale. Following this, I will move on to a final section in which noise is shown to characterise structures on orders of magnitude above and below the immediate human scale. Notably, these orders of magnitude are those from which Norths takes its data: fluctuations in magnetic fields, for example, or seismic activity characteristic of movements of the landscape.

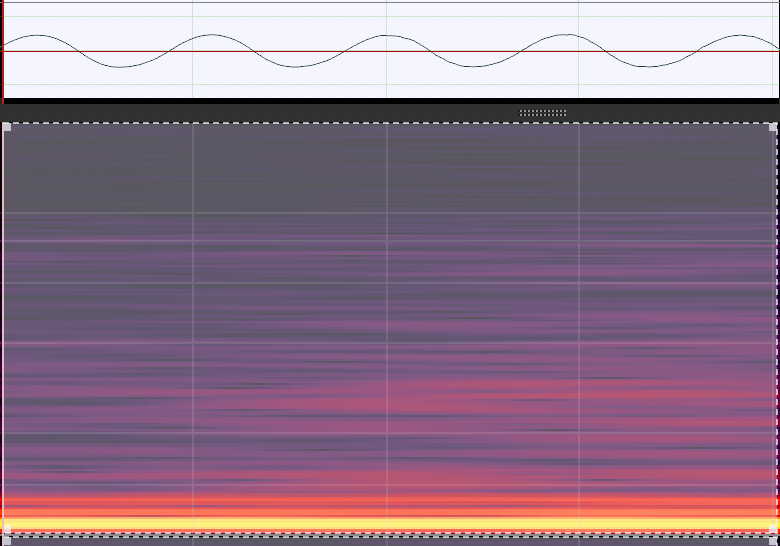

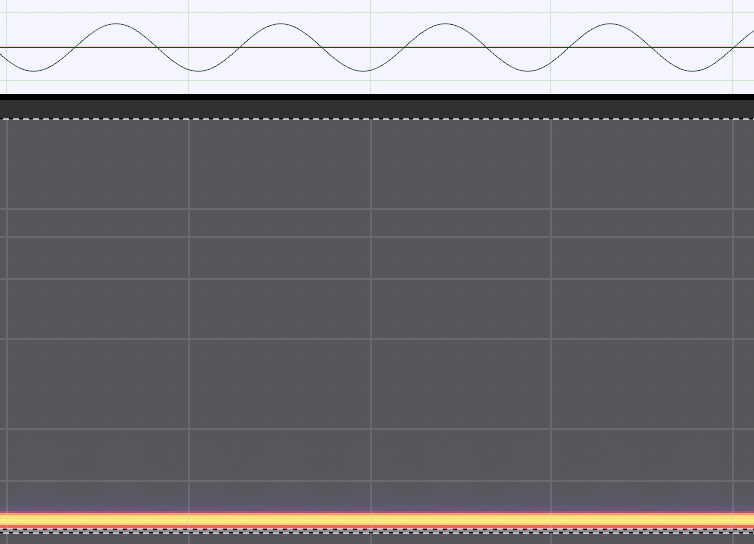

The adjacent images (right) show a 220 hertz sine wave as a function of amplitude over time and FFT spectral frequency display (below). The top image was recorded within a DSP module, the lower recorded in a room in the open air.

The two images adjacent show frequency spectra (and amplitude trajectory) over time for a 220 hertz sine tone. The upper image depicts the harmonic spectra of the tone recorded from within the DSP module of a computer. This recording was produced internally without the tone ever sounding in the air (itself a fascinating metaphysical notion). The lower image is of a tone of the same frequency recorded in a room. The coloured bands visible in the lower image represent noise recorded along with the tone, produced by room reflections. Such noise would appear in any room recording, and this recording was made in a quiet space. This contrasts the relatively blacker, and therefore less noisy, recording up top. In studio practice, the goal is generally to approach a result more like that seen on the top, referred to as a ‘clean sound’.

However, if the 220 hertz tone is filtered (removed) from both recordings, the topmost recording pictured becomes something akin to a digitally materialised, virtual ‘silence’ (another fascinating metaphysical notion). What remains in the lower image after the 220 hertz tone is removed (the noise) now represents data about the room.

This noise-data represents the type of phenomena processed by our ears and minds as we move through spaces. We learn about our environments relationally, as Alva Noë might term it, through our embodiment and embeddedness (Noë 2005). Furthermore, the process occurs unbeknown to us, as demonstrated in Polanyi’s The Tacit Dimension (Polanyi 1966). This is the sort of data that helps us to understand a tunnel that we pass through without recourse to a detailed inspection of the architecture. Room data of this sort is similar to what can be gathered purposefully for the construction of an artificial model of a room and applied in creating a ‘convolution reverb’. Thus, a sound can be made to behave as though ‘implanted’ in a previously recorded and thereby datafied space. A recording can thus be produced to sound as though it took place in a specific room without it ever physically existing there (yet another fascinating metaphysical notion).

Noise in the room recording above has been discussed as data that embodies information about the context of a signal. Perspectives, frames of reference, and intentionality help determine what we experience, how we think, how we interpret, and what we do next. Do we filter out the noise or treat it as data about place?

Place as Data and Experience

The previous section highlighted the fact that ‘noise’ and ‘data’ are interchangeable depending on the perspective of the person paying attention to them. This is key to many insights that have emerged while developing the pieces in Norths. In Norths, noise, measurement artefacts, malfunctioning technology, or unexpected signals reveal themselves as sources of insight that subsequently lead the design and development of these works. In fact, all the pieces in this first iteration of Norths in some way become frameworks for allowing these phenomena to ‘show themselves’. The details of this are discussed in the sections related to the individual works following this discussion of Norths in general.

In considering future directions for Norths-works, I am encouraged by observations made by the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot. An important 1963 paper of Mandelbrot’s resulted from research at IBM examining noise in phone lines (Mandelbrot and Berger 1963):

(Mandelbrot) discovered that the noise tended to appear in bunches, with patterns that remained constant whether plotted by the second or by the hour.

There was a larger structure at work. This type of activity - measuring structures and making sense of seeming chaos - would become Mandelbrot’s life’s work. The net result was nothing less than a new geometry of the cosmos. (IBM 2023)

Examination of this noise led to the development of what Mandelbrot was to term ‘Fractal Geometry’ (Mandelbrot 1982). Fractal geometry revealed structures residing on a hidden order of magnitude within the existing forms we perceive all around us, as well as those that exceed the human scale. Error, mundane noise in phone lines, revealed a phenomenon that turned out to be a clue to the existence of an unforeseen structural dimension.

Learning about how Mandelbrot took noise as subject rather than artefact is encouraging. I naively embraced the results of systemic ‘misbehaviour’ in Norths-works like Constellation. Mandelbrot goes much further, framing what might otherwise be discarded or ignored in the central position for his research.

A final example is particularly suited to the leap from examination of noise to insight about form, as I have been discussing in light of the Norths-works. From his initial work in studying how phone line errors were clustered, Mandelbrot found a principle for the distances between changes of direction in trajectories of particles exhibiting Brownian motion. He realised that this microscopic phenomenon could be extended to macroscopic phenomena, like large-scale landforms, and presented this in a 1967 paper entitled ‘How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension’ (Mandelbrot 1967). In doing so, he encountered a fundamental indeterminacy in relation to the coastline that is suggestive of my previous discussion of indeterminacy in measurement as it emerges from the Norths-works.

According to Mandelbrot, ‘an arbitrariness of measurement’ is revealed when one examines a coastline ‘with a metre stick, on foot, with an out of focus camera, or rigorously sketches the coast as a map in pointillist fashion’ (Mandelbrot 1977). Mandelbrot’s discussion of this discovery can be read through Norths to reveal and exemplify three key limits to certainty. Two concern acts of measurement and data collection, and the third concerns notions of quantitative certainty based on measurement itself.

To begin with, imagine that we set out to measure the distance between any two points A and B along a coast. The first issue is that the measuring apparatus itself limits the precision of the measurement. The metre stick only supplies comparative certainty to the scale at which its lines are etched. Were the coastal span between A and B straight (rather than a fractal curve), its distance could still not be determined beyond the precision of this rough instrument.

Compounding this is that the measuring apparatus is necessarily rigid. The rigidity of bodies like rulers and grids is the quality which helps to measure departure from rigidity. Yet this inherent rigidity in the measuring tool is problematic because the span of coast between A and B is not only complex, it is nowhere straight. While the coast can be described by a fractal dimension, linear measurement will be frustrated.

Riddled with bays and inlets across every scale, curvature shows itself to require finer measurements beyond the divisions of the metre stick. Imagining that further divisions could be added even to a microscopic scale would not solve the problem. Further curves on ‘smaller’ scales are found when seeking the limits of the curves already apprehended. Each measured curve adds to the length of the span previously measured. As one descends to smaller and smaller scales, the additions of distance become less but nevertheless continue. The coast, it seems, is infinite. The more precisely one attempts to measure it, the longer it gets.

Finally, the dimensional evasiveness of the object being measured results in an ‘entanglement’ of the measuring agent and apparatus (here, ‘metre stick’) with the phenomenon being measured (here, the coast). One cannot measure the coast because one’s metre stick and oneself are in the way. This is akin to attempting to take a photograph with a camera so small that one’s thumb is always covering the lens. The result is data about one’s thumb rather the object intended.

These limits on measurement are also limits on what kind of mappings may be made between data and phenomena. In this way they offer a critique of data as a stand-in for phenomena along the lines of that undertaken in Norths. The results of both suggest that attempts to separate oneself from the objects of one’s experience eventually result in frustrating though revealing boundaries. The connectiveness implied here, that an experimenter is already entangled in apparatus and phenomena, recalls Barad’s epistem-ontology discussed at the beginning of this exposition (Barad 2007). A kindred notion is expressed by Mandelbrot in a statement that could also be taken for a summary of key insights from Norths:

The basic uncertainty concerning the value of a coastline’s length cannot be legislated away … In one manner or another, the concept of geographic length is not as inoffensive as it seems. It is not now, nor has it ever been, entirely ‘objective.’ The observer inevitably intervenes in its definition. (Mandelbrot 1977)

In Norths, the search for something that seemed so simple has resulted in research pointing towards infinity. It is easier to reach for something concrete. Stretching upward, reaching for the north star reveals still further questions:

How many norths are there?

Is the meaning of something as seemingly simple and trivial as ‘north’ fixed or mutable?

While undoubtably a useful construction, what happens when a simple concept cannot be measured with accuracy, when standards come into conflict with one another, or when the tools for measurement return chaotic data?

I’ve had no real experience of the North.

I’ve remained, of necessity, an outsider.

Glenn Gould, The Idea of North (Gould 1967)

An illustration of Brownian motion as studied by Mandelbrot, from one of the sources he cites in (1977). ‘Three tracings of the motion of colloidal particles of radius 0.53 µm, as seen under the microscope, are displayed. Successive positions every 30 seconds are joined by straight line segments (the mesh size is 3.2 µm)’ (Perrin, 1909).

The photos below show a gradual progression of increasing detail regarding the curvature of a coast. The process could be continued beyond the resolution of the camera and into the molecular region, and yet the measurement would remain limited in its precision.

The images show two recordings of a 220 hertz sine tone. The image above depicts the harmonic spectra of a tone recorded from within the DSP module of a computer. This has therefore never sounded in air. The image below is of the same tone recorded in a room. The coloured bands visible in the lower image represent ‘noise’ added to the tone from room reflections, as contrasted to the relatively blacker, therefore noiseless, upper tone. In studio practice, one might filter the noise from the tone depicted below to attempt to approach a result more like that seen above: a ‘clean sound’. However, you could alternatively filter the 220 hertz tone out of the noisy signal, and use the remaining noise to learn about the resonances of the space the tone was recorded in. This provides an example of how noise often contains embedded, embodied information about the context of a signal.