A key attribute of the media score lies in its capacity to reflect its own role as a mediator between an idea and an action—an action that might result in sound or, indeed, any other outcome. The quality of its mediacy becomes perceptible, tangible, and unavoidable. The concept of hypermediacy, a term coined by David Bolter and Richard Grusin in their book Remediation[1], captures this essence. Originally describing “a style of visual language whose goal is to remind the viewer of the medium"[2], the term finds new relevance in the context of a score. A score’s ability to mediate between different modes of expression while simultaneously revealing its own mediating capacity makes hypermediacy an apt descriptor.

Translating between symbols and sound is fundamental to how a musician reads a score. The mechanics of how musical notation encodes the rules of musical patterns are deeply intertwined with how we understand music and reveals what aspects are prioritised in that music—it is almost akin to a language in itself. Almost, but not entirely, because the medium is not totally transparent. Musical notation introduces a layer of ambiguity, an invitation for interpretation, or even misinterpretation. Tempo, dynamics even the tuning of pitches are all relative concepts (or at least in relation to each other and to the canon of work preceding them). Yet, the score as we know it, remains an entrenched medium shared between the composer and the musician that negotiates these relations.

When this is shared with an audience, when the audience is given a glimpse behind the curtain, something changes: the act of mediation becomes a focal point, it becomes problematised. The ways in which information is conveyed to the musicians become part of the musical space. A media score highlights the process of how the composer’s intention, in sound or musical gesture, is encoded and then decoded by the musicians. These are brought to the foreground, they are emphasised. This is how hypermediacy can be manifest in the score itself, how it can lead to different ways of thinking about sound and performance.

Music notation systems have been categorised as either ‘descriptive’ or ‘prescriptive’, with Western classical music typically incorporating a combination of both. Charles Seeger's well-known 1958 essay addresses this issue from an ethnomusicological perspective[3], exploring the challenge of documenting one musical tradition using a system designed for another. Descriptive notation conveys what one is supposed to hear, while prescriptive notation offers guidance on how to perform it—the former focuses on representation, the latter on mediation[4]. Media scores tend to rely heavily on prescriptive notation, which can take various forms, including graphic elements, text, tablature, or even metaphorical expressions. Moreover, one might argue that the ultimate form of descriptive notation is the audio recording. Béla Bartók’s statement that “The only really true notations are the soundtracks on the record itself[5],” implies that audio recordings can also serve as a form of score.

Prescriptive notations, with a high degree of hypermediacy, can also be metaphorical. Similar to conceptual metaphors—where one idea is described in terms of another—a notational system can establish a relationship with sound that is not immediately recognisable. The metaphor serves as a way of presenting an apparent contrast in a different medium, inviting varied perspectives. Rather than explaining, it leaves elements open for the musician (or the spectator, in the case of shared scores) to interpret. This creates a score that poses questions to the musician (or audience) rather than prescribing or describing how it should sound.

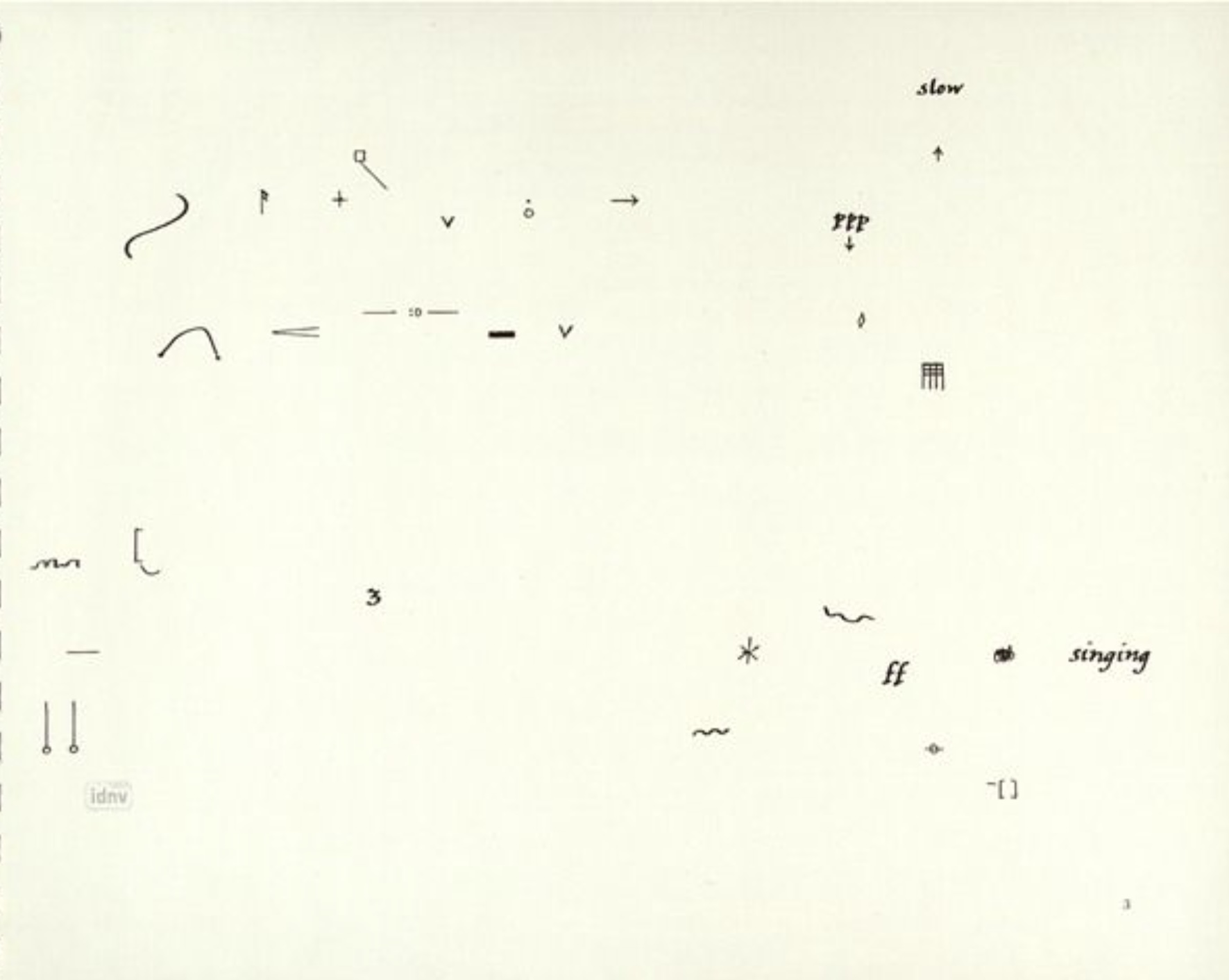

A beautiful example of this is Christian Wolff’s Edges (1968), written for the improvised music collective AMM (comprising then of Cornelius Cardew, Keith Rowe, and Eddie Prévost amongst others). In this work, consisting of a page of musical symbols (see below), he asks the musicians to interpret the set of signs as "limits or points that can be reached but not exploited[6]”. This creates a puzzle for the musicians in how one should interpret the score. The mediacy of the musical notation is problematised. How does one “reach” the various symbols without “exploiting” them[7]? The score creates such a particular sense of introspection while playing, which heightens the awareness of the intention and the sound producing gesture. Each sound one makes is almost like a question to oneself, has the ‘edge’ between reaching and exploiting been crossed? When does one ‘arrive’ at the sound? How does one navigate between the spaces of various symbols without already ‘exploiting’ them. These questions seem to be an inherent part of the piece and can be given answers in the performance of the score.

The graphical score of Christian Wolff's Edges. An interpretation by guitarist Keith Rowe, one of the original members of AMM, can be found here.

Another wonderful example of a score that problematises its own mediacy is Alvin Lucier’s Memory Space (1970). A text score, which instructs the musician to create their own personal score by various means:

“Go to an outside environment (urban, rural, hostile, benign) and record by any means (memory, written notations, tape recordings) the sound situations of those environments. Returning to an inside performance space at any time later, recreate, solely by means of your voices and instruments, and with the aid of your memory devices (without additions, deletions, improvisation, interpretation) those outside sound situations."

The openness of these instructions belies the difficulty in dealing with the idea of how one can translate a sound from one medium into another, and what kind oftransformation of information takes place in the exchange. While interpreting this work, a musician becomes intensely aware of the process by which one listens, both consciously and subconsciously – how one is constantly decoding sounds in one’s environment, filtering out essential and non-essential information, discerning patterns and imposing an emotional reading on them. The work also brings up performative issues – since the musicians are interpreting their individual ‘memory spaces’ (either through a recording or a self-made writtten score) collectively in the same concert space. How do these overlapping spaces relate to one another? What is being communicated[8]?

Both these scores bring to the fore the question of their hypermediacy. It’s an example of how ambiguity in the way the score is defined can open up the creativity of the musicians. There is distinctive identity of purpose and character in these scores, that despite their openness, indicates a clear approach one can take in performing them. Yet, the inherent questioning of the medium through which the idea is conveyed remains integral to these pieces.

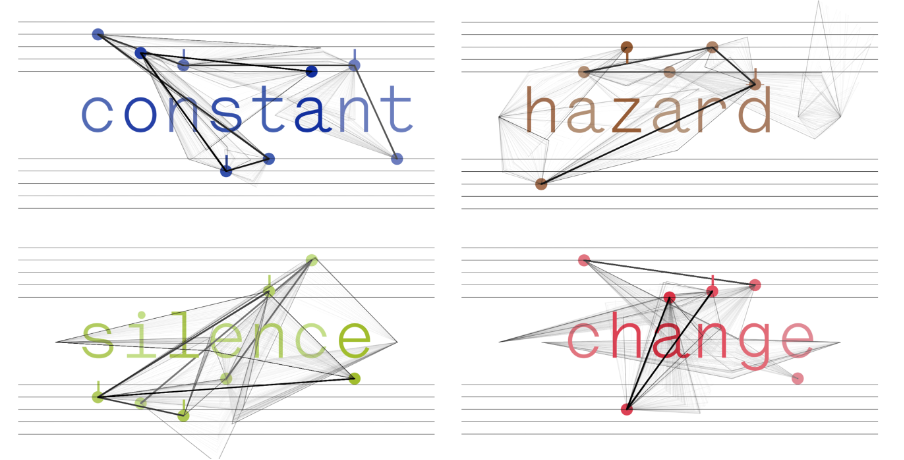

In my own work, this idea came to the fore while I was working on Oneiricon (2014), an app-score I developed in 2014 for Maze, first performed at the Angelica Festival in Bologna. The piece’s triple function as a score, an e-book, and an instrument raised questions about its primary purpose. The score itself offers two reading modes: one where the player scrolls through the actual book, word by word, and another where words are randomly selected from the text and morphed with the next random word. The letters in these words are mapped to notes based on frequency charts, allowing the player to navigate and manipulate the resulting speeds and sounds. When we initially performed the piece, I created a set of guidelines or rules for how it should be played. However, as the piece was performed more frequently, I realised it could function without these predefined rules. Instead, the score could serve as a framework of possibilities, encouraging players to engage with its various attributes—reading, playing, and interpreting—in diverse ways. This highlighted its hypermediacy and underscored the importance of adapting and using it differently depending on the context, an essential aspect of the work.

Excerpt from Oneiricon performed by Ensemble Maze, Splendor, 26.05.17. Full video here.

Next: Aboutness

Notes

[1] Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

[2] Ibid. p.22

[3] Seeger, Charles. "Prescriptive and Descriptive Music-Writing." The Musical Quarterly 44, no. 2 (April 1958): 184–195. Oxford University Press.

[4] Kanno, Mieko. 2007. “Prescriptive Notation: Limits and Challenges.” Contemporary Music Review 26 (2): 231–54. doi:10.1080/07494460701250890.

[5] Bartók, Béla, and Albert B. Lord. Serbo-Croatian Folk Songs: Texts and Transcriptions of Seventy-Five Folk Songs from the Milman Parry Collection and a Morphology of Serbo-Croatian Folk Melodies. New York: Columbia University Press, 1951.

[6] Wolff, Christian. Edges: For Any Number of Players, Any Numbers of Instruments. London: Peters Edition, 2002.

[7] I gained valuable insight into this when I had the privilege, together with students of the kHz kollektiv, of performing this with Christian Wollff in 2014, around the time of his 80th birthday, at the Royal Conservatory, The Hague.

[8] This text was adapted from liner notes that I have written for the CD of (Amsterdam) Memory Space performed by MAZE and released on Unsounds 37U.