9____Mutability

The philosophical underpinning of the idea of mutability extends back to the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus, who’s famous “panta rei” (“everything flows”) and the metaphor of never stepping into the same river twice, asserts that change is the natural essence of reality. In the Christian tradition, mutability is associated with the created world, which contrasts with the immutable nature of God. The concept of mutability also captivated the Romantic poets, with both Percy Bysshe Shelley (as explored later) and William Wordsworth writing poems titled Mutability, dealing with the transience of the human experience, suggesting that embracing change can be as natural and harmonious as music:

“From low to high doth dissolution climb,

And sink from high to low, along a scale

Of awful notes, whose concord shall not fail;”[1]

Contemporary ideas of mutability are very much part of the postmodern sensibility where the fluidity of identity and meaning is taken as a given. In a mutable framework, reality becomes a process rather than a fixed entity[2].

Mutability, the state or quality of being changeable, is an attribute of the media score that could be said to be relevant in most of the previous chapters. Mutability in an artwork challenges the notion of it being a fixed, unchanging entity, consistent with every interaction. For example, is a musical composition akin to a book or a painting—something static—or does it evolve with each performance? Undeniably, a musical piece undergoes transformation every time it is played, influenced by the performer, context, and interpretation. Yet, at its essence, it is often conceived as a fixed creation, with its core structure and intent remaining constant.

In fine art, the concept of mutability is evident in works from the Process Art and Land Art movements. Richard Serra’s sculptures, such as Tilted Arc, undergo transformation over time as they are exposed to the elements. Andy Goldsworthy’s site-specific installations, crafted from natural materials, are designed to evolve or disintegrate due to natural forces, emphasizing impermanence. Similarly, Tony Conrad’s Yellow Movies explore mutability through house paint applied to large sheets of paper, which gradually turns yellow over decades—a slow, deliberate transformation Conrad considered a film of extended duration.

In music, similar works explore the process of gradual transformation over time, such as William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops. This piece reveals the effects of the physical deterioration of tape loops recorded two decades earlier, with the decaying sounds creating a poignant and evolving auditory experience.

In the digital realm, art project dealing with mutability can be more easily realized because of the natural changeability of data. A great example of this in early net art is Molecular Clinic 1.0 by Seiko Mikami. In this work, the molecular structure of a virtual spider can be interacted with by users online, by exchanging or replacing molecules[3], transforming in unpredictable ways.

Beyond differing interpretations of a work, what aspects of a composition can be said to be mutable? Some of the works discussed previously challenge this notion or, at the very least, expand the concept of what elements are fixed and what are open to change. Structural mutability can emerge through choices made by the interpreter. In the 1960s, a wave of European avant-garde pieces exploring aleatoric forms introduced the possibility of changeable structures. Works such as Klavierstück XI by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Domaines by Pierre Boulez exemplify the concept of “mobile form”, where parts of the structure can be rearranged.

John Cage’s work offers an excellent example of the varying degrees of mutability that can exist within a score. Cartridge Music, previously discussed, demonstrates a piece that requires pre-composition to be performed. The score provides a set of materials that go beyond the permutations of a given structure, as seen in Boulez’s “mobile form”. Instead, it allows for an almost infinite rearrangement of possible sound events, which the performers must define and create themselves. Another model for a more open approach might be his Roaratorio, where the performance depends on source material that has yet to be defined by the composer. Cage gives a formula (one might say an algorithm) as to how to build the piece, which consists of an instruction on how to translate any book into a performance. In the case of Roaratorio, this became “an Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake”, using the dataset of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. What is left of the composer’s intentionality in this approach? Knowing Cage’s propensity to use chance procedures when making decisive artistic choices, this was a way of lessening the authority of the composer. But more importantly, this type of work describes a set of situations that can occur as a starting point but where the outcome is open. Does this make it a ‘mutable’ composition?

Is it possible to imagine a work that begins in one state and gradually transforms into something entirely different, or remains in a constant state of flux? Such transformation would not rely solely on human interaction but could emerge through internal generative or autopoietic processes, or in response to external environmental changes. Defining a composition in this way becomes increasingly feasible within the realm of data-driven art. Beyond the purely artistic fascination with such an approach, one might ask: why would this be desired?

In her book Interactive Technologies and Music Making, Tracy Redhead explores how interactive technologies have been changing the approach to music production. She uses the term “transmutable” to suggest that in many applied situations where music could be used, such as video games, apps and interactive art works, virtual and augmented reality projects, the role of music need not be fixed and can best be conceived as dynamic.

“Transmutability is fundamentally about change: the extent and capacity for music to evolve or be modified, primarily through the lens of data manipulating musical forms.”[4]

The notion of a composition built around unfixed or unstable elements—where the work itself is in a state of flux—offers exciting possibilities. Such an approach challenges traditional ideas of permanence and even authorship in art. It opens the door to creating works that could be said to be animate in some way, responsive to external inputs, and reflective of ever-changing contexts. In the coming years, this will surely lead to different forms of expression, where the boundaries between composition, interpretation, and environment blur in a way that we have not seen before.

At the time of writing this research paper, in 2024 I began working on a

large-scale collaborative work, titled Mutability which was presented as a six-hour concert installation by ASKO | Schönberg at the Holland Festival in June 2024. Dealing with some of the ideas described above, the project aimed to explore how a given source material could evolve and mutate over several hours through a combination of guided improvisation and generative algorithms. It explores the capacity of music to transition fluidly between different states, creating a continuously shifting sonic landscape.

Twelve composers were invited to create miniatures for solo instruments or voices, performed by 12 musicians[5]. These miniatures served as the foundational material, morphing and mutating into new forms throughout the performance.

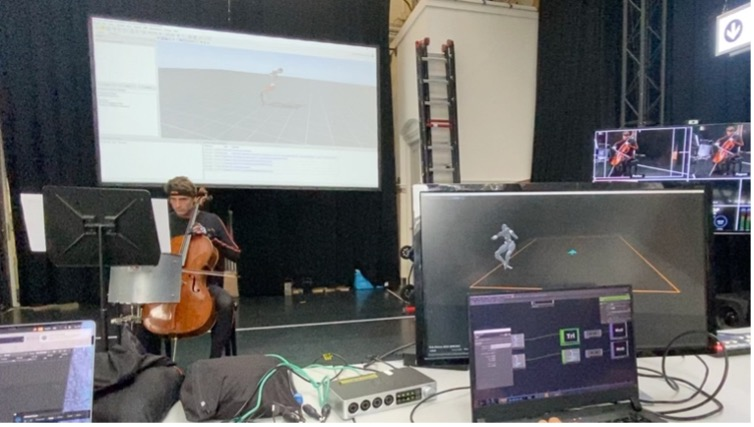

This transformation was achieved both through computer algorithms and the musicians’ live adaptation and reinterpretation of one another’s material. The 12 compositions were pre-recorded, capturing both audio and visual data, including motion capture to track the performers’ movements. This data was used to generate a "forest" of mutable visual forms and sounds that surrounded the live musicians. At various points during the performance, the musicians played their pieces—either in their original form or transformed—across different stages in the space. Detailed analysis of the compositions, combined with meticulous metadata tagging, formed the basis for creating algorithms that sorted and recombined the recorded data in countless ways. This process mirrored the approach taken in Fundaments and Variants.

The conceptual foundation of Mutability, as well as its title, is drawn from Percy Bysshe Shelley's famous poemof the same name[6]. This reference resonates not only with the theme of material transience—central to the work's exploration of constant transformation—but also with its connection to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, where the poem is quoted. In Frankenstein, the question of what it means to be human amidst technological advancement looms large, and this query was at the forefront of my thoughts when incorporating algorithms and generative strategies into the piece. The interplay between the organic and the artificial, between creation and mutation, aligns with these philosophical underpinnings.

Jan Nieuwenhuis expressed this relationship in his program notes for the performance:

“Mutability straddles the age-old dividing line between humanity and technology. We enrich ourselves through technology and call this civilization. At the same time, countless algorithms control our lives unnoticed: they choose the ads that fit our interests, streaming services decide what we watch and listen to, and they confirm our views and delusions. Kyriakides turns predictability upside down and uses this same kind of technology to arrive at new sounds, rather than feeding listeners more of the same. Though in this case he did not compose a single note himself, in doing so he touches on the essence of music: it is only ever mutable.”[7]

Another literary inspiration for Mutability was Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1969). In this two-part novel, Calvino weaves narratives using the structure of Tarot cards. The characters, mysteriously struck mute after arriving at a castle deep in the forest, can only communicate their stories through the placement of these cards. As each traveller lays down their cards, a structure emerges on the table, with the images crossing and overlapping—just as their destinies intertwine. This imagery, of individuals expressing their unique stories visually rather than verbally and their narratives interweaving, offered a metaphor for how to work with the twelve musical identities in Mutability.

The project began with collecting 12 diverse musical pieces, some as scores and others as recordings due to their improvised nature. Each piece reflected a unique artistic voice, showcasing the creativity of the composers. However, this diversity also posed analytical challenges, as the pieces did not adhere to uniform parameters like pitch or timbre, complicating comparisons. Despite this, live performance mitigated these challenges, with musicians adapting their material to align with the algorithmic choices that were made.

The algorithms in Mutability, adapted from Fundaments & Variants, guided both material selection and musician instructions. Musicians received these instructions in advance, learning to respond to algorithmic signals and adapt their pieces accordingly. A crucial principle was that musicians used only material from their own "songs," so that their contributions could be heard to evolve and intertwine with other’s material throughout the course of the piece.

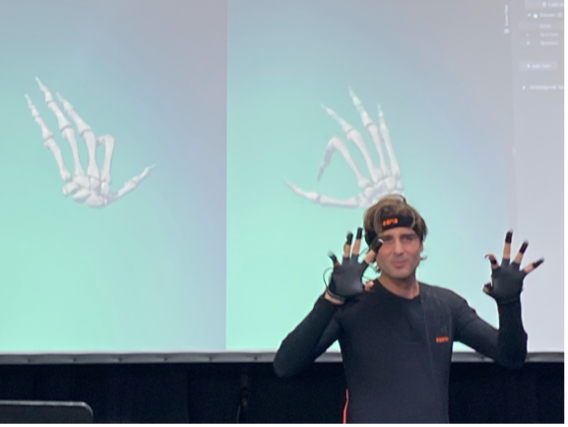

Instead of traditional green-screen recordings as was done in Fundaments and Variants, motion capture technology was used to record the musicians' movements, creating fluid digital avatars for the performance. Collaborating with Innovation:Lab, sessions in Utrecht captured both motion and audio data. Layers of sound were developed from these recordings, including pre-processed “forest sounds” and live-processed fragments, alongside a harmonic sine-tone layer generated by a Java algorithm.

Communication with the musicians was facilitated through iPads using a JavaScript-based code. This system originated as a Processing (Java) patch that I had initially developed and was later translated into JavaScript by Darien Brito. The resulting tool, referred to as the "media score," served as the primary interface for the musicians during the performance. Using a network to connect approximately 20 iPads—including those used by musicians, technicians, and crew—provided a powerful and efficient way to transmit score information. This setup ensured that everyone had a constant, real-time update on the current state of the score.

The score interface included several key elements. The name of the algorithm, a time bar tracked section timing. The instrument graphic visualized dynamic interactions between the instruments, and chorusing notes provided algorithmically generated pitches on staves for musicians to incorporate during chorusing sections.

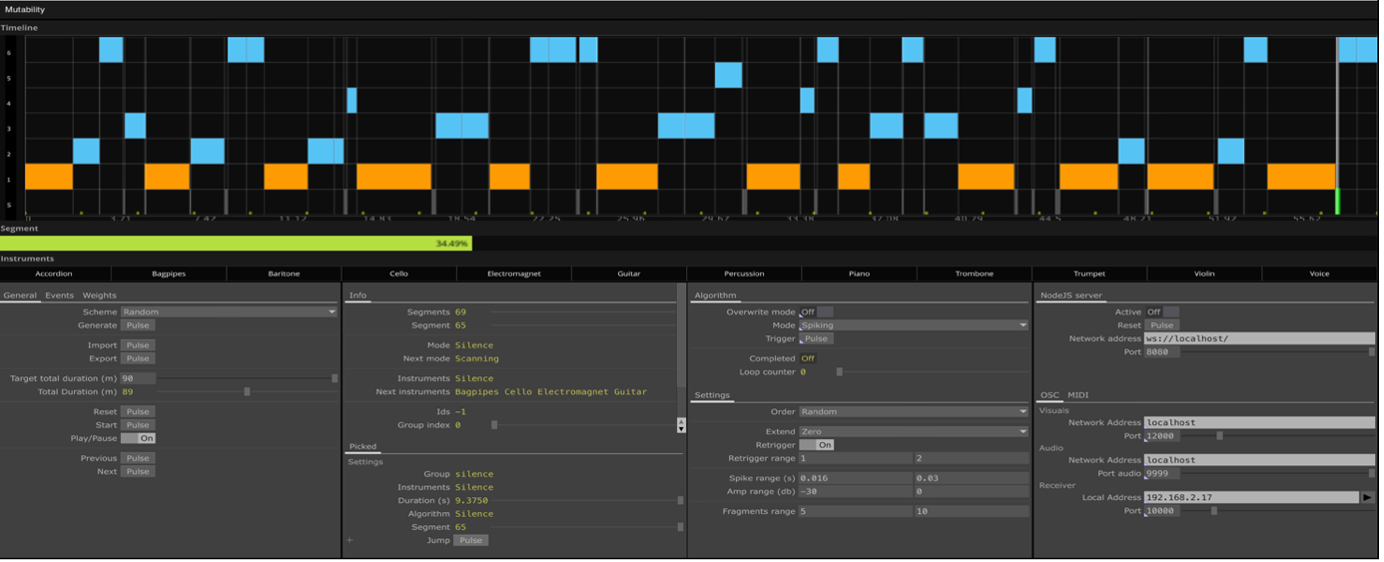

At the core of controlling the audio and visual layers of Mutability was the "master clock," designed by Darien Brito and implemented in Touch Designer. This system provided a complete overview of the activity for each 90-minute block of the performance (four blocks in total, resulting in a six-hour performance at the Holland Festival). The timeline for each show was generated in advance, offering a detailed structure. The timeline featured three distinct states of activity:

Orange blocks: Represented solos—each solo piece was performed in its entirety, lasting about 2–4 minutes each.

Thin grey blocks: Indicated tutti sections, where all musicians could draw material from the algorithmically generated harmonies displayed on their iPads.

Blue blocks: Denoted duos to sextets, where smaller groupings of musicians performed based on various algorithms.

For the live performance, sound control was managed via an Ableton Live patch, enhanced by a Max4Live extension. This system received precise timing information for the 12 original audio layers from Touch Designer over a network. For example, if the "repitching" algorithm was selected, it might isolate fragments containing Bb notes from only the piano and cello recordings. The timing of these Bb occurrences would then be sent to the Ableton Live patch, where the piano and cello recordings would play in two dedicated channels. Each of the 12 algorithms functioned differently but adhered to the same overarching principle: all algorithmic control was executed through Python scripts embedded in Touch Designer or JavaScript running on the master computer.

The background consisted of various layers of processed sound derived from the 12 solos, which I referred to as "forest" sounds. My intention was to evoke a living, organic environment inspired by the forest setting in Italo Calvino’s book. These sounds mimicked the calls of insects and birds but were entirely generated from the solo recordings. The layers included:

The undergrowth: a time-stretched and transposed layer, creating a low harmonic bed.

The noise threads: featuring high-pitched resonances produced by extreme equalization and freezing the high partials of the solos.

The cicada pulse: achieved through granulation and pulsing, combined with extreme amplitude modulation and filter shaping.

The animals: A freeform, algorithmically generated granulation layer, that intermittently flashes by.

The visuals for Mutability were created by Darien Brito and featured various types of generative visual material. These visuals operated on different scales of granularity, as if observing a living organism both microscopically and from afar—at times blending and mutating seamlessly between these perspectives. The projections were displayed on various screens and monitors throughout the space, sometimes as a single unified image and at other times divided across the room, including the wall lights. The elements included: A dynamic particle system responsive to musicians' motion-capture data; avatar forms, based on human shapes, visualized the musicians' movements, creating ghostly, distorted forms, abstracted through 3D rendering; wall light patterns projecting color field animations during chorusing sections.

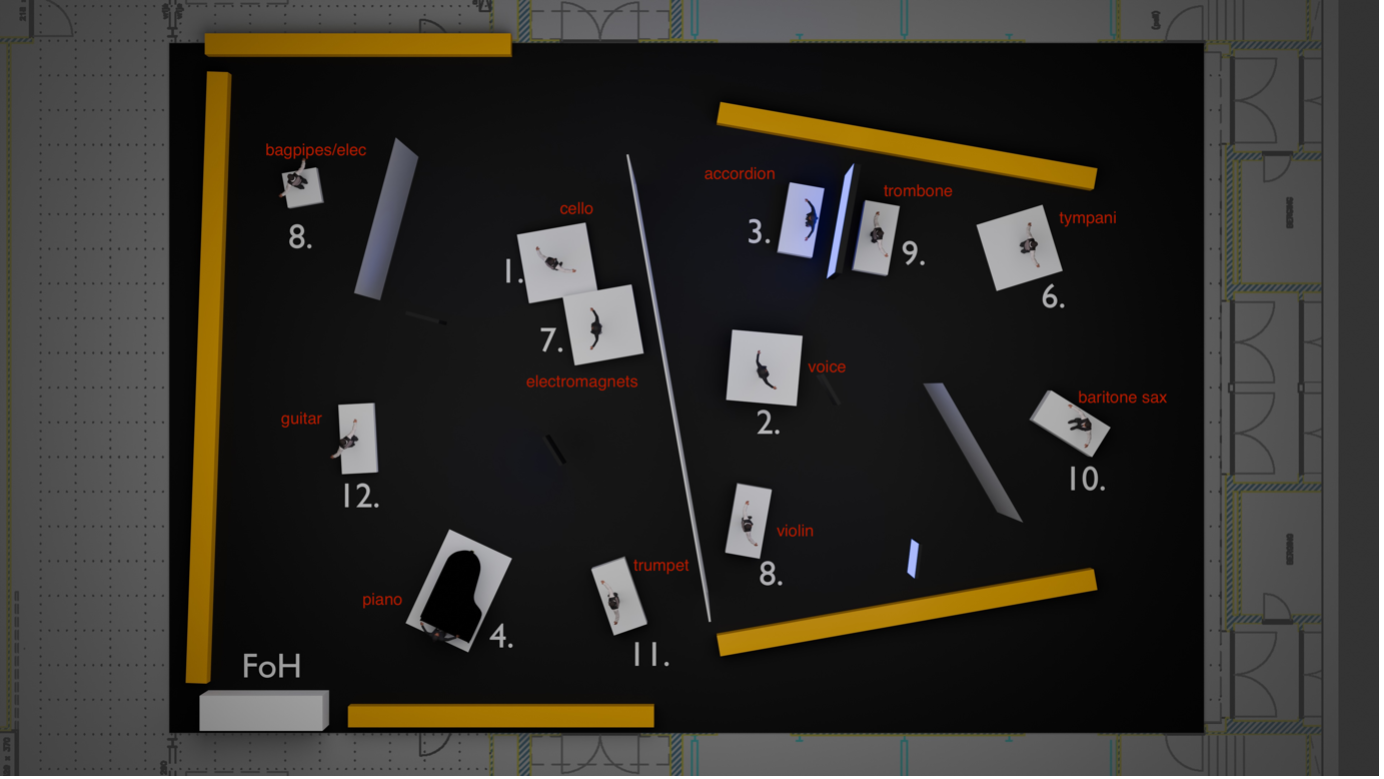

The scenographic concept by Theun Mosk/Ruimtetijd created a dynamic environment for audience interaction, emphasizing movement and multiple perspectives. The space allowed attendees to walk, sit, or stand, with a balcony offering a quieter, elevated view. Musicians performed on raised platforms facing different directions, separated yet connected to the audience, surrounded by screens that divided the room into sections. A striking 12 x 7-meter transparent Hologauze screen bisected the space, serving as the central visual divider, complemented by two smaller Hologauze screens and various LED screens and monitors, some suspended overhead for detailed imagery. This immersive design evoked a sense of exploration, resembling a playground or enchanted forest, where attendees could experience the performance from diverse vantage points.

One of my main concerns was how the musicians would cope with the six-hour performance. Would they have enough energy and focus to maintain their concentration for the entire duration? Both from my own perspective and from their feedback, the six hours seemed to pass remarkably quickly—they even felt they could have continued longer.

I had also asked the musicians to progressively incorporate material from other musicians throughout the performance—a method of "infecting" their own material with that of others. This was intended to foster a human and intuitive form of mutation, an aspect that excited me the most. What struck me was how experienced and sensitive musicians could adapt and transform the material in ways that were often surprising—far beyond the predictable patterns of the algorithms. This complementary form of human adaptation gave the piece an emotional edge.

One of my key takeaways from this experience was the exploration of how a performance can deviate from the conventions of classical music. By redefining the relationship between musicians, audience, and space, it’s possible to create an entirely different way of listening[8]. This was evident not only in the spatial configuration but also in the layered listening experience that the musical material encouraged. Each composed solo piece had its own distinct rules and language, coexisting with the surrounding sounds and improvisations. The use of an open-score format for the musicians further contributed to keeping the performance fluid and unpredictable.

5 minute impression of Mutability, from the performance at Holland Festival 2024. Full 90 minute version of first block can be seen here.

Next: Conclusion

Notes

[1] Opening lines of William Wordsworth’s Mutability (1821).

[2] This is something that is explored in Gilles Deleuze’s concept of becoming in Difference and Repetition, Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

[3] https://v2.nl/works/molecular-clinic-1-0

[4] Redhead, Tracy. Interactive Technologies and Music Making: Transmutable Music. 1st ed. Focal Press, 2024

[5] The full list of collaborators on this project were: Composers (of solo pieces): Silvia Borzelli, Trevor Grahl, Claudio Jacomucci, Dmitri Kourliandski, Anna Korsun, Andy Moor, Brigitta Muntendorf, Geneviève Murphy, Mayke Nas, Aurélie Nyirabikali Lierman, Martijn Padding, Jasna Veličković. Performers: Pepe Garcia, Sebastiaan van Halsema, Claudio Jacomucci, Sebastiaan Kemner, Arthur Kerklaan, David Kweksilber, Geneviève Murphy, Andy Moor, Aurélie Nyirabikali Lierman, Pauline Post, Joseph Puglia, Jasna Veličković. The rest of the team consisted of: Darien Brito (Audio-visual art, creative coding), Theun Mosk, Cas Dekker (Scenography), Nina Kraszewska (sound), Niels Weber (Creative technology), with Asko|Schönberg, Holland Festival and Innovation:Lab as co-producers. I was credited with concept, artistic direction, composition and sound design.

[6] We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon. How restlessly they speed and gleam and quiver, Streaking the darkness radiantly! yet soon Night closes round, and they are lost for ever: —

Or like forgotten lyres whose dissonant strings Give various response to each varying blast, To whose frail frame no second motion brings One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest—a dream has power to poison sleep; We rise—one wandering thought pollutes the day; We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep, Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:—

It is the same!—For, be it joy or sorrow, The path of its departure still is free; Man's yesterday may ne'er be like his morrow; Nought may endure but Mutability.

[7] https://hollandfestival.nl/nl/mutability

[8] From the review in the Volkskrant: “Walking through the Muziekgebouw in Amsterdam feels like a journey into a strange universe. From every perspective, the network of twelve musicians sounds different.” https://volkskrant.nl/muziek/bij-mutability-zijn-de-musici-beelden-in-een-beeldentuin-die-muziek-spelen-volgens-algoritmen-verbluffend~b018cb6a/