5____Interactivity

A broad definition of interactivity can be understood as a two-way flow of information, applicable to both human and non-human interfaces. An instrument, for example, can be considered interactive as it responds to the manipulation of the user and provides sound feedback in return. In fact, most music-making is inherently interactive, whether in the exchange between musicians and their audience or among musicians themselves. However, this interactivity traditionally does not extend to the relationship between a musician and a conventional score or notation.

Digital technology has changed this dynamic, as interactivity is a fundamental characteristic of computers and computer interfaces. When applied to a score, this creates an analogy in which the score itself becomes an instrument—manipulatable by the user, whether musicians or audience. The result can be a stimulus in a specific modality, typically auditory or visual, which is either immediately perceptible to the audience or serves as a response cue for the musicians.

Interactive scores always require some way in which a change, trigger or sensory input can affect the course of the composition. These sensory inputs can be generated through physical actions such as clicking a button, swiping across a touch interface, or performing a gestural movement detected by cameras, accelerometers, muscle sensors, infrared or ultrasonic sensors, or GPS trackers. Other inputs might include text commands, changes in lighting, audio signal analysis, or even facial gestures. The vast array of input sensors not only expands the possibilities for instruments but also introduces new ways of "navigating" a score, transforming how the composition is communicated to musicians.

What are the benefits of making a score as malleable as an instrument? That it can be played, controlled, and modulated through interaction, and not only taken as a source of information. This meta-level of a score can bring different affordances. On a simple level (though not insignificant), it can be used to synchronise changes of section, either linear or non-linear. Using a trigger, the musicians or audience can move through various scenes, musical material, scripted or generative. This affords a control of macro-structure that can be centralised or decentralised into different pathways.

Interaction on a deeper level of the composition, could affect the type of material that is being chosen or generated. These types of interaction are usually algorithmically composed, so that there is a causal relationship between an input and its effect on the score. Even if there is a random or chaotic relationship, that is usually understood a priori by the musicians, to give some sense of agency. Networked situations where the interaction can be an aggregate of different decisions can give a lesser sense of direct control, but can create an awareness of a collective agency shared amongst remote participants.

Interaction can occur at various stages of the creative process. For instance, a type of interaction is invited during the preparation of a piece for performance. Works like John Cage’s Variations series, the Cartridge Music, or Robert Ashley’s In memoriam...KIT CARSON (opera) require many decisions to be made before they can be performed. This could be described as a one-time interaction, representing a realization of the open possibilities provided by the composition. However, once the performance begins, the score—as it has been rendered—remains unchanged.

The interaction that occurs on the performance level between musicians and score, is the one that is afforded by the use of digital technology, where an HID interface or a ‘computer listening’ algorithm can steer the outcome of a score. A rare example of a pre-digital work that suggests an algorithmic interactivity between musicians is Christian Wolff’s Music for 1, 2, or 3 People, where the score defines the interaction between players rather than having fixed relationships. I define this as algorithmic due to the specific type of language used to describe the decisions a performer must make while listening to the other players.

“A single note with a tie coming onto it, means play after a previous note has began, hold till it stops.

Two notes joined by a tie means start anytime, hold till another sounds starts, finish anytime.

A single note with a tie going away from it, means start at the same time as another sound, and stop before it does.

Three notes tied means hold till another sound starts, continue holding anytime after the sounds has stopped."[1]

This type of Boolean interaction defined within the score is a rare and elegant example of how algorithmic thinking shapes the musicians' approach to listening and responding. A media score affords the possibility of creating these interactions through digital algorithms that respond to both the sensory input and the structure of the composition.

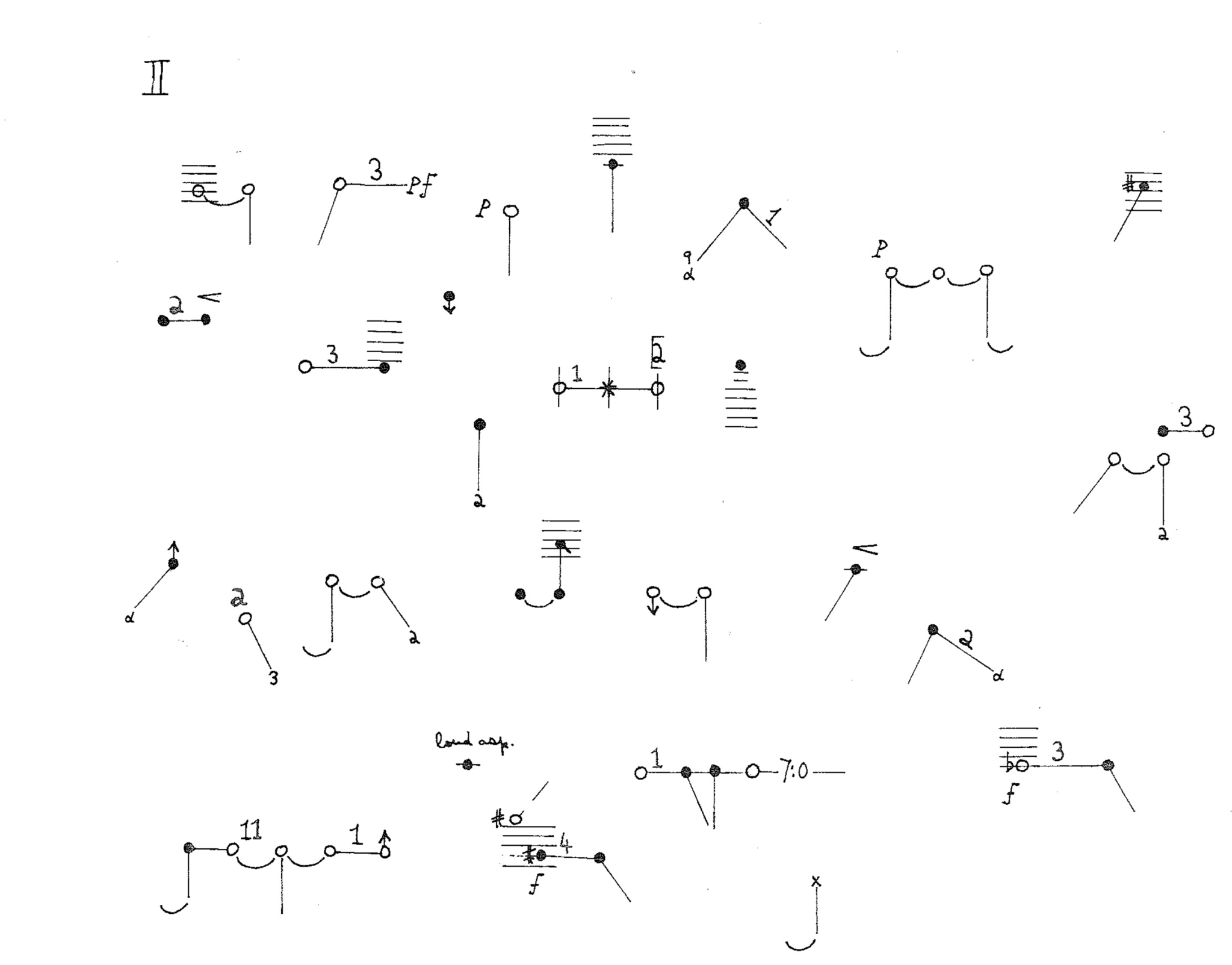

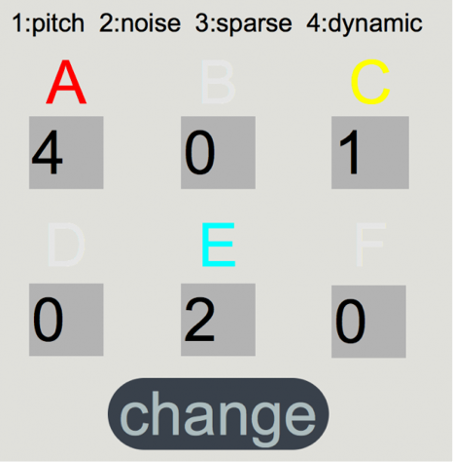

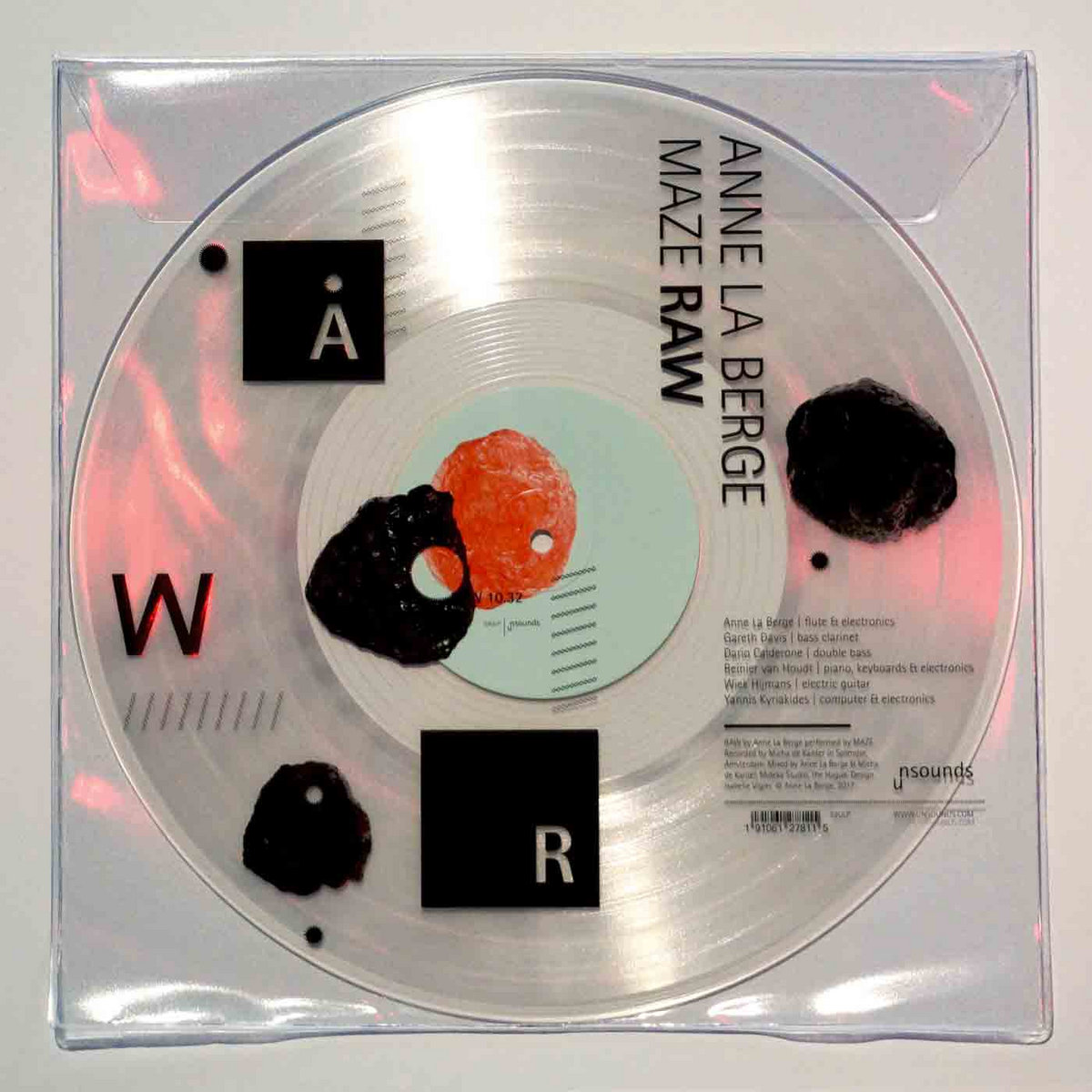

Two interesting contemporary examples of using interactivity to navigate within a score are Anne La Berge’s Raw, and Maya Verlaak’s Us butterflies. In Raw[2], musicians interact through a score interface which lets them know if they should play, and if so what kind of material: pitch, noise, sparse or dynamic (see below). These kind of parameters (two nouns, two adjectives) stem from Anne La Berge’s background both in improvisation and electronic music where there is enough space given to the performer to interpret, but where the contextual meaning is very clear. The beauty of the piece lies in the interaction of the performers. Each player has the ability to change the current instrumentation selection, by pressing “change” on their iOS score interface. This randomly shuffles the selection, and at the same time, triggers voice samples (quotes by members of MAZE about what the concept of ‘Raw’ means to them).

The ability of each performer to influence the course of the piece on an individual level, with immediate effects on the overall outcome, is a powerful dynamic. This not only highlights the collective's ability to shape the composition but also underscores the personal relationships among the musicians in the group. Does one have the right to interrupt a musical situation unfolding between other players in order to change it? Pressing "change" can feel like cutting into a conversation. Yet, this "impolite" interaction makes the piece immensely enjoyable to play. If anything, it strengthens the group's sense of collectivity, as the power to alter the course of the piece is equally distributed among all members.

Under the hood, this piece is created in a Max patch and distributed to iPads via the network using the Cycling 74 App Mira. All iPads running the score are synchronized. There is no need for the audience to see the score, so there is no master projection; the score remains viewable and playable only by the performers.

In Maya Verlaak’s Us butterflies[3] every musician’s actions have global consequences for the entire group. The performers are interconnected within what the composer describes as a “sensitive system,” drawing on Edward Lorenz’s concept of the butterfly effect, where any small fluctuation at a local level can drastically alter the system on a global scale[4].

The piece consists of four parts, each named after different butterfly species, which some of the data is based on. In the first part, De Dagpauwoog, a connection is established between the pitches played on the guitar, the number of butterflies displayed on a screen, and the speed at which the guitar sound is processed. A relationship is also formed with the other musicians, who attempt to "catch" the generated butterflies. This interaction is further translated into the physical presence of musicians and balloons within the performance space, monitored by six microphones. As Verlaak explains:

“Each physical movement and sound is triggered by something and causes something else; it becomes a feedback loop for the produced sounds and movements.”[5]

In Part 2, The Gehakkelde Aurelia, the complexity increases. The wing speed of the butterflies, translated into tempi and pitch, is compared with the movement of balloons (measured by microphones inside the balloons). The musicians’ positions within the performance space are also factored in, influencing a chord that gradually morphs between different frequencies, which the musicians must mimic. A computer algorithm constantly calculates differences or discrepancies and feeds this data back into the space. In Parts 3 and 4—Bruine Zandoogje and Het Kleine Koolwitje, respectively—the complexity takes another turn with the introduction of a live-generated score featuring musical notation. The network of feedback loops between the musicians' sounds and actions, the processing, and the projections remains both intricate and playful. This playfulness partly stems from Verlaak’s incorporation of game-like elements into the score. Musicians are assigned specific tasks to complete, balancing the intent of the game with an awareness of the evolving musical situations that emerge.

These are two examples of how interactive networks can be established between musicians and the score in diverse ways. The contrast between the elegant simplicity of Raw and the intricate networked feedback loops of Us Butterflies underscores the varied forms that score interaction can take, each resulting in dynamic and engaging works. A defining feature of interactive scores is the collective shaping of a piece’s form by the musicians.

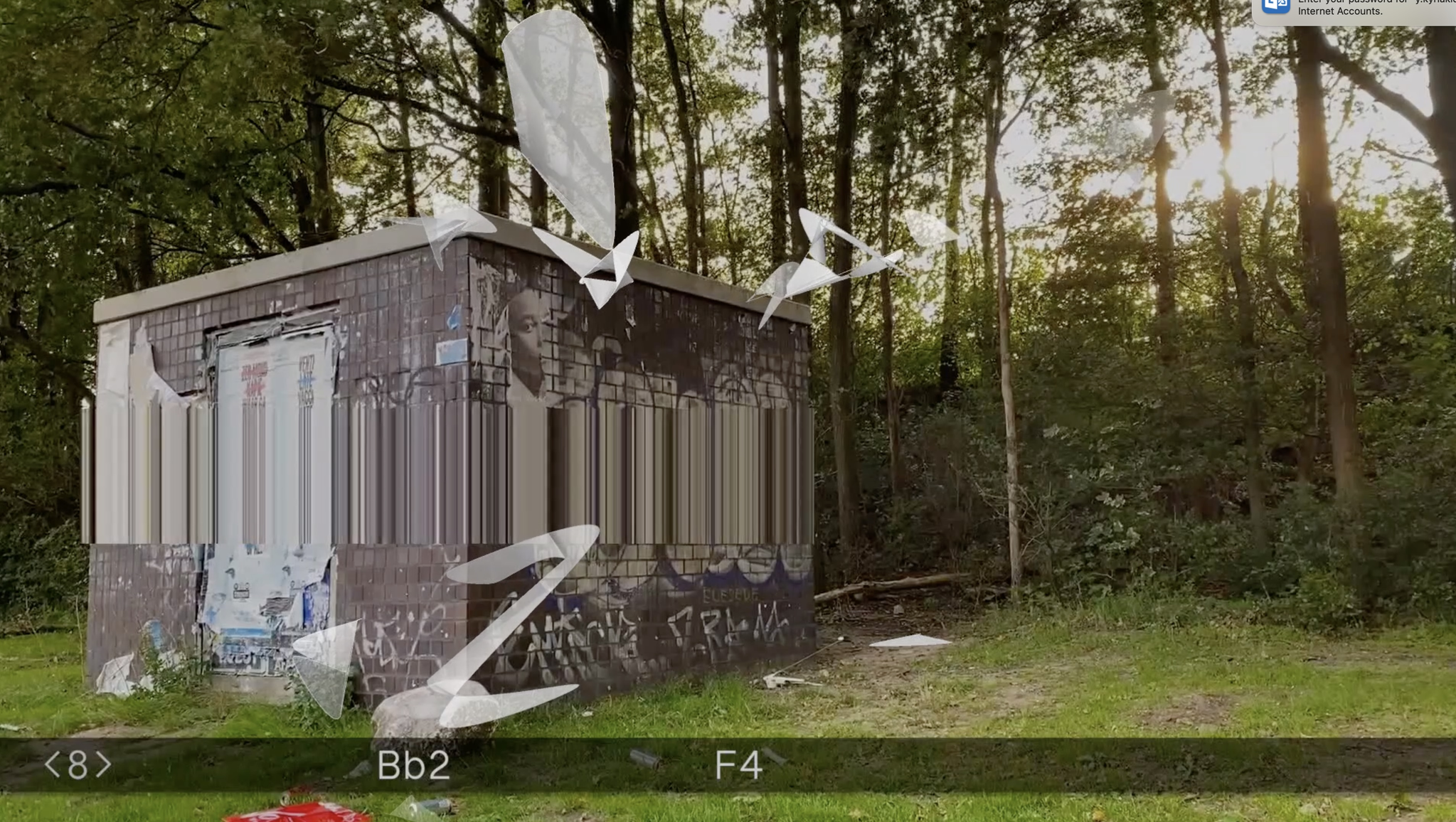

Another example of a relatively simple use of interactive score which leads to a complexity is in my own piece Orbital (2020). This is an audio-visual score for ensemble of any size. It is a journey around the Amsterdam ring road - the A10 - made during the first period of lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic April to September 2020. The score is comprised of 74 scenes, audio-visual recordings from places around the A10, in which various musical parameters can be interpreted.

A microphone is set up in the space and musicians come to it one at a time, to play solos. The amplitude of the sound is then used to trigger randomly generated “kite” shapes on the video, the louder the sound the bigger the kite. These kite shapes are then used by the rest of the musicians following the video score, to connect to one of the pitches shown in the lower part of the image. They play that pitch modulating it in timbre and volume depending on the course of the kite. The more active the solo, the more kites are created, and hence more activity from the rest of the musicians. Because the central microphone controls the generation of kites, the course and shape of the piece is dependant on the activity of the soloists. There is a responsibility that is shared between the collective in how the piece unfolds.

Exceprt from Orbital, performed by Ensemble MAZE and BUI, Splendor, Nov 26, 2022. Full video here.

Interaction can also extend to the audience, inviting them into the creative space of the musicians, in the construction of a score. This concept has been explored in various ways by bands like Tin Men and the Telephone, and composers such as Alison Isadora and Alessandro Bosetti. The participatory aspect, which allows the audience to not only the change the course of the piece, but to also become performers is a topic which is too big to cover here, but is a vital aspect of interaction and immersive performance.

The participatory aspect—where the audience is not only able to influence the course of the piece but can also take on the role of performers—is a multifaceted topic, far too big to explore fully here. However, it remains an important and growing part of interactive and immersive musical performance, bluring the traditional boundaries between performer and spectator.

Next: Multimodality

Notes

[1] From the instructions to the score of Christian Wolff’s Music for 1, 2, or 3 People.

[2] Originally written for the ensemble MAZE, RAW was designed for an instrumentation that included flute with electronics, bass clarinet, double bass, electric guitar, piano with electronics, and synthesizers.

[3] First performed: 24 November 2024 at Hermes studio, Antwerp. HERMES Ensemble:

Voice: Esther-Elisabeth Rispens Flute: Karin de Fleyt, Viola: Esther Coorevits, Electric guitar: Pieter-Jan Vercammen Piano: Bert De Rycke, Percussion: Wim Pelgrims Electronics: Maya Verlaak, Choreography: Amit Palgi, Composition & concept: Maya Verlaak

[4] Further reading on the Butterfly Effect: Lorenz, Edward N. The Essence of Chaos. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993.

[5] From the score of Us Butterflies, shared by the composer.