6____Multimodality

The concept of Umwelt, put forward by the biologist Jakob von Uexküll refers to the unique perceptual world experienced by an organism, According to von Uexküll, each organism lives within a subjective reality shaped by its sensory capacities and biological needs, which determine how it interprets and interacts with its environment[1]. For instance, a tick perceives the world in terms of heat, light, and the smell of mammalian skin, while a human's Umwelt encompasses a vastly broader array of stimuli. This idea highlights that reality is not a singular, objective construct but a mosaic of overlapping subjective experiences.

Applying Jakob von Uexküll's concept of Umwelt to a concert situation can reveal how each participant experiences the event differently based on their sensory and perceptual frameworks. For the musician, the Umwelt is shaped by auditory cues, the notes and rhythms of the music they are playing, tactile feedback from their instrument, and perhaps visual connection with their fellow musicians and audience. In contrast, the audience members’ Umwelt might centre on the music’s emotional resonance, the physical sensations of the sound in the space, or the visual spectacle of the performance. A security guard at the event, however, may focus on crowd movements, safety risks, and communication from colleagues, forming an entirely different Umwelt. These overlapping but distinct perceptual worlds underscore how individuals at the same event inhabit unique subjective realities, all informed by their roles, sensory abilities, and intentions.

In a performance involving a media score, the audience can see, hear, and feel the performers’ actions within the same space, yet their interpretation of the experience may differ significantly. Drawing on Uexküll's semiotic model, this divergence arises because the processes of sign interpretation are linked to distinct functional cycles (Funktionskreise[2]), wherein specific sensory inputs trigger one response in a performer and an entirely different one in an audience member. While these interactions are shaped by shared social contexts—such as the conventions of behaviour in a concert or theatre—it’s important to recognise that neither a musician’s nor an audience member’s subjective experience can be wholly reduced to predictable patterns. Instead, the Umwelt of each individual reflects a dynamic interplay between personal perception, action, and the broader social and sensory environment. This highlights the complexity of meaning-making in shared artistic spaces.

Considering the many senses that can be engaged in a performance space, a media score can incorporate a wide range of modalities as input signals, drawing from any sensory experiences available to humans and non-humans. Non-humans are included here in the way that sensory interfaces can be designed to translate signals that humans cannot naturally perceive—such as infrasound, ultrasound, radio waves, or infrared radiation—into perceptible forms. These interfaces enable humans to engage with sensory dimensions that would otherwise remain inaccessible, expanding the scope of sensory input in a performance context. A conventional musical score employs the surrogate language of notation, a visual representation of sounds that translates an auditory experience into a form readable by the eyes. Musicians primarily rely on sight and hearing, along with touch to interact with their instruments. In terms of using expanded sensory input for media scores, so far what we have discussed relies primarily on hearing and sight, but sensory information based on touch has become an increasingly used modality to transmit score information, through haptic devices.

Sandeep Bhagwati’s body:suit:score which he defines as a situational score, in that it “delivers time- and context-sensitive score information to musicians at the moment when it becomes relevant[3].” The motivation to create a body suit that can be used by the musician to receive score information, came from the need to have a score that is movable, “locative” as he would say, where the information depends on where the musician receives it. The suit itself consists of multiple vibrotactile elements arranged in different areas of the body suit. These are used to send score information directly to the body of the musician via Wi-Fi. An ongoing project, at the time of writing, several works have been written, including by Bhagwati himself exploring the possibilities that a wearable medium like this can bring. As well as dealing with the many technical problems an undertaking like this entails, he asks the all important question, which underpins many approaches to dealing with new technologies and innovative score approaches:

“Which music or kind of musicking could not be imagined, let alone be performed, without it?"[4]

This poitns to the crux of how new technologies have always gone hand in hand in creating new possibilities for artists. The development of new instruments has continuously opened up other ways of percveiving music. This also resonates with the famous saying by the Persian Sufi poet Rumi quoted by video artist Bill Viola:

"New organs of perception come into being as a result of necessity—therefore, increase your necessity so that you may increase your perception."[5]

Another composer who uses touch sensors as one of the primary medium is Kuba Krzewiński. In many of his works, the tactile medium becomes highlighted either in a performative sense, where musicians explore their instruments in an unconventional way, with touch being the principal focus, or in a form where vibration, or sound felt replaces sound that is heard.

In his installation Touch Me, presented at the Warsaw Autumn Festival 2023, the audience engages with a tactile installation integrated into a performer’s body, where every interaction resonates with amplified and transformed sounds. Using haptic sensors and contact microphones, the touch of the audience, either directly on the performer, or through the construction of the installation, effects the actions of the performer, and the resultant sound heard through the speakers. This work examines touch as both an intimate source of sound and a channel for human connection that is often constrained by societal norms.

Another approach to wearable instruments is as an interface to translate the movement of the musician to sound, where the body is as both a receiver and transmitter of information. This is an area explored by Icelandic multidisciplinary artist Sól Ey. In her ongoing work Hreyfð (2021-) she designed a wearable gestural instrument that uses microphones, speakers, a microcontroller, and gyroscope signals to create and manipulate audio feedback[6]. With speakers attached to the body, the performer becomes the sound source, transforming physical gestures into a sonic choreography. The proximity of one performer to another can also affect the resulting sound, because any sound can enter any microphone, so the strategy of how the performers relate to one another becomes an aspect of the score that the performers have to be aware of, and can manipulate.

“Proximity makes the performer-instruments become a single entity, and it’s very different to play because you have to think of all your sounds and movements in relation to this entity[7].”

The piece incorporates two interrelated aspects of scoring: a sound score and a choreographic score. Throughout the performance, the prominence of each fluctuates, with one occasionally taking precedence over the other.

“The dancers are instructed with sound score, where each “character” has a specific register, loudness, wave-form reference, amount of noise, etc. and these characters are use as references for the score. There’s also a choreography that is partly scored and partly just memorised/video documented. I’d say both sound and choreography scores are equally important in the instructions, although sometimes it varies since sometimes one is more dominant than other[8].”

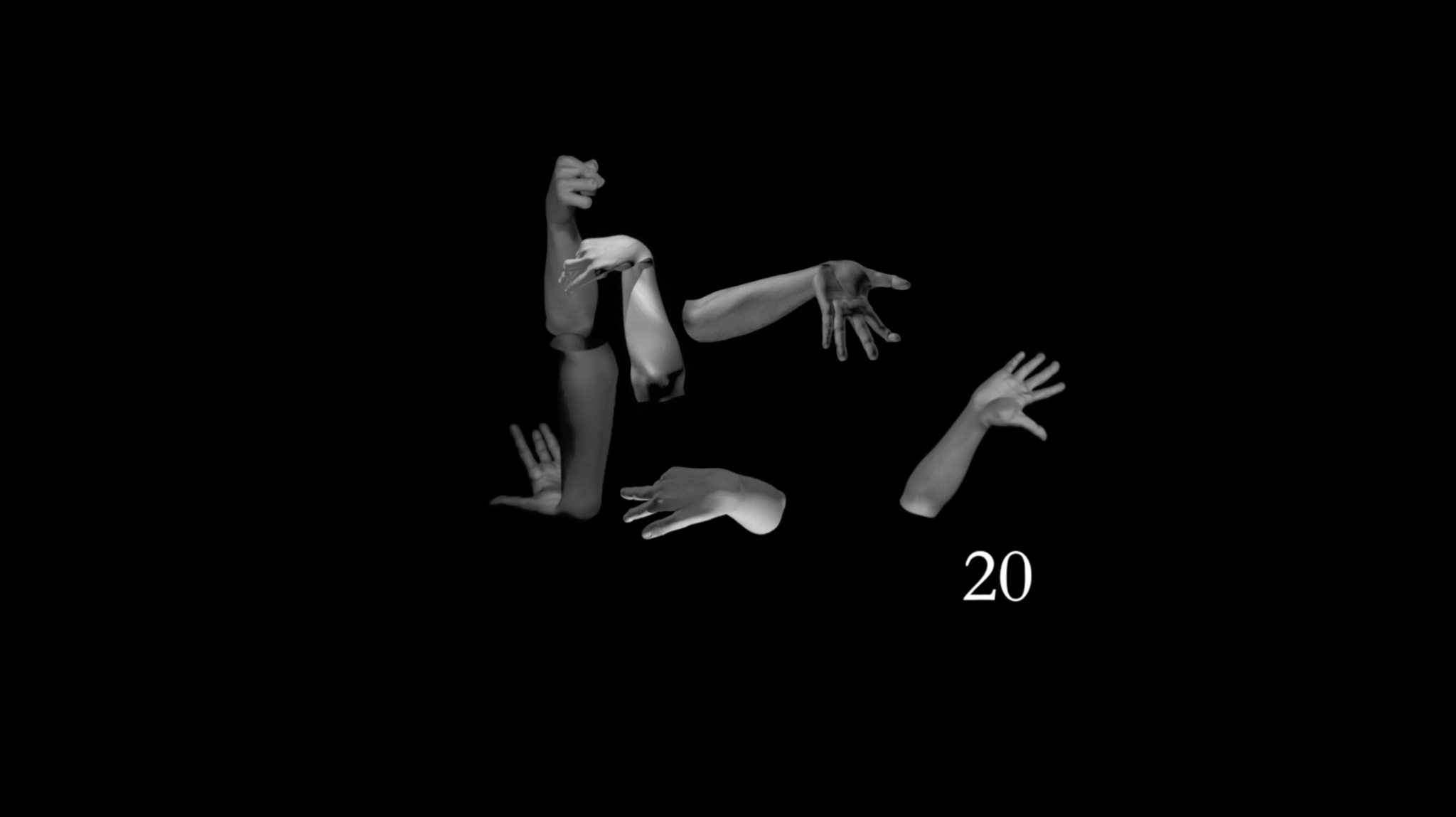

I have explored the potential of gestural controllers in several works, including the multidisciplinary pieces Unmute and Hands. In Hands (2021), a video score featuring a 3D animation of hand gestures guides the performance. Both works incorporate Myo controllers[9],which transmit muscle and movement data to a computer running various synthesis programs to shape the sound. A sound buffer is recorded live by the musicians each time they receive a signal—either as a vibration through the wearable device or via a light next to their microphone. The musicians then interact with the recorded sound buffer, locating it within a 360-degree spatial mapping around them. Using granular synthesis algorithms, they manipulate and transform the sound in real time, using the movement and rhythm shown on the video score as a guide.

In this score, the information is distributed among several senses. There is first the visual connection of the video score, the audio that is on the video that reinforces the rhythm and the audio that helps the musicians guide themselves in finding elements of their sound in the space around them, and finally the haptic signals that they receive in order to synchronize their actions.

Excerpt from the performance of Hands by HIIIT, Theater aan het Spui, September 2024. Full video here.

In the examples above, the haptic senses are used as a way of interfacing between sound and a tactile experience of the world. However, the other Aristotelian senses—smell and taste—have also been explored in musical contexts, often as a means of enriching the audience’s sensory experience. Works of this kind that come to mind are Calliope Tsoupaki’s Narcissus: play for music & scent (2013), a work for 6 musicians, where together with a perfumer Tanja Deurloo from Annindriya, she designed a scent that is diffused in the concert space during the performance of the work, each section of the piece coinciding with the addition of another layer of scent, in order to give the composite fragrance at the end. Another is Ben Houge’s so-called food operas, where a real-time generative soundtrack is created to accompany a specially curated multi-course meal by chef Jason Bond.[10]

Next: Generativity

Notes

[1] von Uexküll, Jakob. A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans: With a Theory of Meaning. Translated by Joseph D. O’Neil. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

[2] Kull, Kalevi. “Jakob von Uexküll: An Introduction.” Sign Systems Studies 32, no. 1 (2004): 281–294.

[3] Bhagwati, S: Musicking the Body Electric: the “Body: Suit:Score” as a Polyvalent Score Interface for Situational Scores.In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Technologies for Music Notation and Representation (TENOR), Cambridge, UK (2016).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Viola, Bill. Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House: Writings 1973–1994. Edited by Robert Violette. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; London: Anthony d'Offay Gallery, 1995.

[6] Documentation of performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jCz6EOObs2g

[7] From an email correspondance with the composer.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Myo is a gesture control armband from Thalamic Labs (now defunct) that senses muscle tension (8 EMG sensors) and hand movement.

[10] https://newmusicusa.org/nmbx/food-opera-merging-taste-and-sound-in-real-time/