7____Generativity

Nature demonstrates that complex and unexpected patterns can arise from simple rules or systems without any direct human intervention. During the creative process, artists design algorithms, systems, or sets of constraints, allowing interactions within these frameworks to shape the outcomes. Related concepts such as autopoiesis, autonomy, algorithms, and emergence are often associated with this approach.

A key aspect of generative art is the balance between human and non-human decision-making, where control and unpredictability interact. This balance allows the emergent qualities of the system to define the content, form, or both. For example, cellular automata or neural networks—often described as emergent systems—can produce surprising and unanticipated results, uncovering patterns beyond the artist's initial expectations. These emergent properties may be inspired by nature, where intricate structures arise from basic principles, or they may be entirely artificial, detached from existing models.

Media scores have the capacity to utilise generativity as a defining quality, built on frameworks that are inherently digital and algorithmic. At its most basic level, a composer might define a simple rule or constrain random choices through an algorithm, enabling nearly infinite permutations of a pattern. The output of this generative process can manifest in various forms: scores, audio, visuals, or notation, each of which may suggest diverse paths for performers to explore. This process often mirrors the creative workflow, where an artist refines their system by responding to and guiding the resulting properties to align with their vision, while still preserving the system's autonomy. Andreas Pirchner, in his essay on some of Marko Ciciliani’s “ergodic work”, underscores this interplay of emergence in the relationship between score and performers:

“The notion of emergence helps us to understand a bottom-up process where sets of basic rules constitute the space of possibility offered to the performer. Through their activity, performers traversing this space mediate which manifestations of the composition emerge.”[1]

The integration of algorithmic procedures in generative art challenges traditional notions of authorship, shifting the artist’s role from creator to co-creator or curator of systems. This redefinition was already evident in the reception of John Cage’s work and subsequent generations of experimental composers whose open-form compositions questioned conventional authorship. These works entrusted musicians with greater responsibility in making core artistic decisions. Even in Cage’s early I Ching inspired pieces, where the flip of a coin was used to make decisions based on that ancient Chinese algorithm, we see an early example of constrained randomness generating unexpected musical results. Generative art, in this sense, often emphasises the beauty of the creative process and the interplay between human and non-human agency, rather than focusing solely on the aesthetics of predefined outcomes.

Moving from simple algorithmic rules to complex neural networks and AI, the agency of the human creator becomes increasingly intertwined with the non-human. As the process itself becomes less transparent, the relationship between prompt, process, and resultant material grows more enigmatic. To date, much of AI's use in art has leaned towards curated outputs, where artists select or refine the results of neural networks to align with their vision, discarding what does not. This shift in focus—from transparency in the process to an emphasis on the results—introduces a distinct aesthetic. It suggests a creative practice oriented towards outcomes, fostering an aesthetics of imitation rather than one of generativity. Yet, the capacity to produce infinite variations of given material—despite the lack of total control by the human creator—offers intriguing possibilities. It hints at a way of conceptualising scores or compositions not as fixed entities but as sets of possibilities existing at any given moment, embracing an inherent instability in the outcome.

Composers exploring the possibilities of generative composition in the last 50 years, have included Iannis Xenakis, Clarence Barlow, Gottfried Michael Koenig, and others too many to list. From the point of view of creating real-time scores from generative algorithms Georg Hadju is one of the most prominent one that comes to mind, through the Quintet.net[2], which he calls —a network performance environment[3]. This platform enabled projects that blend interactive and generative elements, serving as an early example of screen-based scores and real-time generated notation, inspiring a growing community of composers integrating these techniques into their work.

Another notable example is Arne Eigenfeldt’s An Unnatural Selection, which employs algorithms inspired by Conway’s Game of Life to generate musical material for musicians to sight-read on tablets. Eigenfeldt’s program notes highlight the challenges performers face: balancing musical complexity with readability, as only highly skilled musicians can execute such works[4]. This approach, which merges traditional musical notation with the possibilities of real-time computer processing, has revealed the limitations of sight-reading in certain contexts, as discussed in various research papers[5].

Outside the realm of academic contemporary music, the concept of generative music has been popularized by Brian Eno, introducing a distinct aesthetic perspective. Eno’s work from the mid-1970s, such as Discreet Music and Music for Airports, draws inspiration from Terry Riley’s tape loops. These works explore the idea that overlapping loops can generate an almost infinite array of variations, creating forms that appear to stretch out endlessly. This approach not only redefines the relationship between musicians and the score but also embraces the notion of boundless, evolving forms, offering a contrasting vision of what generative music can be.

This music is often categorized as "ambient" and is sometimes dismissed by the academic music community. However, it has had a profound influence on the trajectory of electronic music, particularly with the resurgence of modular analog electronics. The creation of generative systems using voltage control—so-called analog computing—has paralleled the advancement of generative algorithms in the digital realm, and this has fed back into different forms of digital music. Examples of musicians employing generative algorithms in this way include Autechre’s Oversteps, Exai, and Elseq, as well as Keith Fullerton Whitman’s Generators.

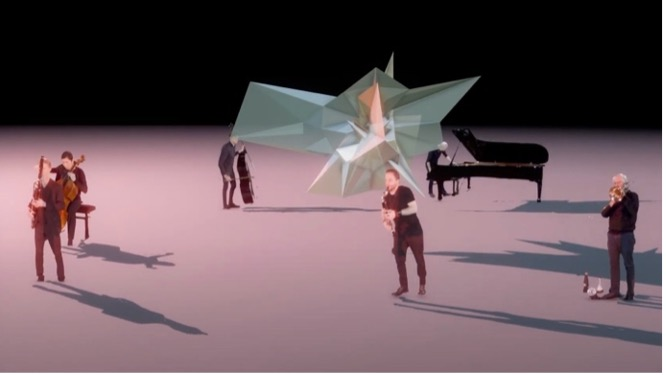

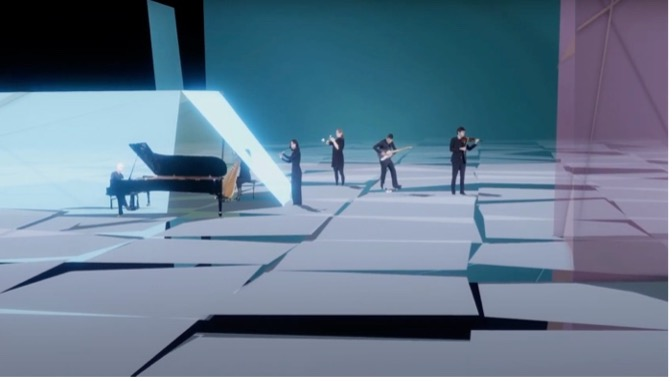

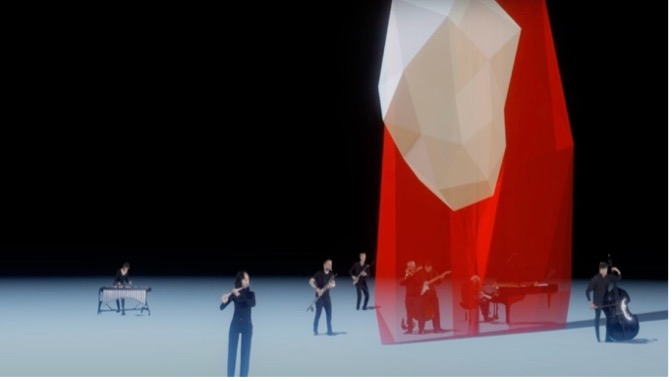

An example of a piece from my own work that utilizes generative algorithms is one that I developed during the Coronavirus lockdown, when a significant portion of our lives were being conducted remotely. Fundaments and Variants (2022) for virtual ensemble, is both an installation and can be used as a score. 14 different algorithms are used to play back different fragments of pre-recorded audio (and video) in relation to the characteristics analysed and defined in the metadata of the audio files.

The programming was developed in collaboration with Darien Brito, using Touch Designer, a node-based programming environment widely used by the audiovisual creative community. It allows for the integration of Python scripts within its architecture through which we defined the 14 different algorithms used in the piece:

scanning, pulsing, oscillating, emptying, pitching, soloing, stretching, noising, coupling, placing, dislocating, spiking, gating and texting.

Due to the location and possibly the parametric nature of the analysis conducted on the recordings, the piece seemed to carry the spectral presence of Arnold Schönberg. The recordings were made with a green screen in the Arnold Schönbergzaal of the old Hague Conservatoire, just before its demolition. I composed 12 short fragments for 12 instruments, each derived from the same tone row, resulting in approximately three minutes of material per instrument.

The algorithms determined how fragments of audio-visual material were selected and treated at any particular moment in the piece. Because of the structure of the code, each time an algorithm is called, a specific limited set of video fragments is chosen and remains available until the next algorithm is called. In this way, each different instance of the same algorithm has a defined characteristic based on a range of polyphony, the start delay of the fragments, and the refresh range. This also applies to the specific visual language per scene: a palette of colours, geometries, camera movements, lighting, and movement of musicians, which can be programmed within a range of random possibilities and can morph between various instances, enabling a constant variation and recognition of the characteristics of each state that the piece is in.

The question as to whether the output of the software could not only be the end in itself but also a score for live musical participation was on my mind as I was finishing the piece. Could the virtual, almost game-like musical world depicted in the videos be used to represent something in the real world?

Excerpt from Fundament & Variants 3.22. Full video of this rendering here.

Next: Spatiality

Notes

[1] Pirchner, Andreas. "Ergodic and Emergent Qualities of Real-Time Scores: Anna & Marie and Gamified Audiovisual Compositions." In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technologies for Music Notation and Representation (TENOR'20), 189–197. Hamburg, Germany: Hamburg University of Music and Drama, 2020.

[2] Code can be found here: https://github.com/HfMT-ZM4/Quintet.net.

[3] Hajdu, Georg. "Automatic Composition and Notation in Network Music Environments." In Proceedings of the Sound and Music Computing Conference (SMC'06), 109–114. Marseille, France, 2006.

[4] https://aeigenfeldt.wordpress.com/an-unnatural-selection/

[5] Freeman, Jason. "Extreme Sight-Reading, Mediated Expression, and Audience Participation: Real-Time Music Notation in Live Performance." Computer Music Journal 32, no. 3 (2008): 25–41.