8____Spatiality

Spatiality in music is a relatively recent area of exploration. While there are historical examples in classical music—from Palestrina, Thomas Tallis, and Giovanni Gabrieli to Charles Ives, Iannis Xenakis, and Karlheinz Stockhausen—where the spatial arrangement of musicians and sound sources is integral to the compositional concept, this discussion focuses on a different aspect. Beyond the various forms of spatial audio designed to enhance the perception of space, I aim to examine how a score itself engages with spatial concepts. Specifically, this involves exploring how a score conveys ideas of spatiality rather than temporality.

Traditional score notation inherently employs spatial concepts to represent time. It is read from left to right at a pace determined by tempo and meter, constructing a timeline of musical events as it unfolds. In this sense, the score functions as a map—not of physical locations, but of how musical events are organized temporally.

Extending this map metaphor, a score can also suggest musical events that are not fixed within a linear timeline. While musicians ultimately perform these events in time, their arrangement in the score may evoke a sense of non-linearity. Such a score may lack a clearly defined beginning, middle, or end, allowing for a more open-ended interpretation of its structure. Indeterminate scores by John Cage, or event scores of Alison Knowles are examples of this.

Another type of score can suggest a spatial arrangement of sound events that requires physical engagement. In this sense, it functions more like a map, describing the spatial relationships between elements. A notable example is the late Tom Johnson’s Nine Bells (1979), where the musician navigates various geometric paths to sound nine bells suspended in a grid. The score, in this case, not only suggests the sequence of actions but also embodies the physical interaction with the spatial arrangement.

This type of score bears similarities to the script/score of Samuel Beckett’s Quad, where a geometrically defined path for four players, accompanied by light and percussion, creates a choreography with a clear sonic outcome.

If we were to read the real world like a score we would perhaps be in to the territory of John Rose and Hollis Taylor’s The Great Fences of Australia, whose piece takes parts of Australia’s fence network and transform it into a musical instrument. Using contact microphones, the duo captures the vibrations and resonances of the fences, that plays with the tensions and contradictions embedded in the fences’ existence. Can this be considered a score? There is a logic to the interaction with the fence that has the properties of a score. It marks out space, it invites interaction with it along its length. The players move through parts of the fence, as if they are reading lines of a musical notation. The fence is naturally also an instrument: a “ giant musical string instruments covering a continent."[1]

In the digital realm, the ability to merge real-world environments with virtual spaces opens up possibilities for navigating the score-space. The immersive qualities found in digital games—where players move through complex, interactive landscapes—can serve as an interesting surrogate for a traditional score. Performers (and audiences) can engage with the score as a way of organising events in a composition, with or without temporality. By integrating interactive elements drawn from the gaming world, composers and performers can leverage tools such as motion tracking, augmented reality overlays, and responsive visuals.

In Tao Sambolec’s Reading (as) Bodies for text, sound, custom software, wireless speakers, and digital positioning system, a performative setting is created that reimagines written text as a graphic landscape and reading as a physical act. This interactive installation uses the exploration of space as its score. During its premiere at V2 in Rotterdam, MAZE performed a short version of the piece. However, the piece is ultimately intended to be experienced directly by the audience themselves.

The text “DESIRE TO SENSE MAKE” is printed on the floor, with a software system linking its written phonemes to pre-recorded spoken phonemes. This text, and its virtual mapping acts as the score. As visitors or performers engage with the text, their movements across it trigger corresponding sounds from wearable loudspeakers, each emitting a unique voice. There is a direct relationship created between their position on the text and the spoken sounds they produce, effectively allowing participants to "step through" the spoken text as they walk across the written words. Sambolec writes about the piece:

“The project investigates the experience of reading as an interface between our interior mental state and the exterior world, asking whether what separates the two is a temporal, flexible and virtual gap, as opposed to a fixed corporal/material border[2].”

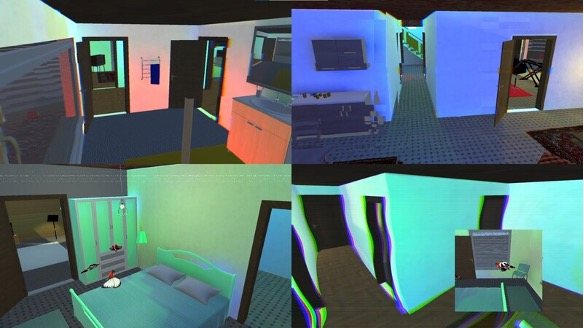

Marco Ciciliani is a composer who has explored this kind of work in several pieces: Kilgore, Anna & Marie, and 11 Rooms. 11 Rooms[3] is a multidisciplinary concert piece that explores the interplay between private and public spaces. Created for the saxophone ensemble KLEXOS, the work integrates video footage of the musicians’ daily activities with a virtual 3D house that is navigated live during the performance by what he names as a “media artist”, alongside the four saxophonists. Within this virtual space, sounds and actions encountered are manipulated in real-time by the musicians using their saxophones—not as traditional instruments, but as resonant chambers to shape the electronic sounds (talk-box and megaphones are attached to the instruments). In this way, the main score of 11 Rooms is a navigable virtual space, that generates sounds to be interacted with by the musicians. The media-artist who is the game-player in the piece, takes on the role with the greatest agency in the work, while the musicians navigate dual roles, serving as both subjects within the virtual space and performers outside it.

The mapping of musical events to spatial dimensions—whether within the physical world or a virtual environment—represents a significant paradigm shift in the possible attributes of a media score. This transition from a purely temporal framework, where events unfold sequentially in time, to a spatial one, where they are distributed across an interactive, navigable terrain, opens up new possibilities for composition and performance.

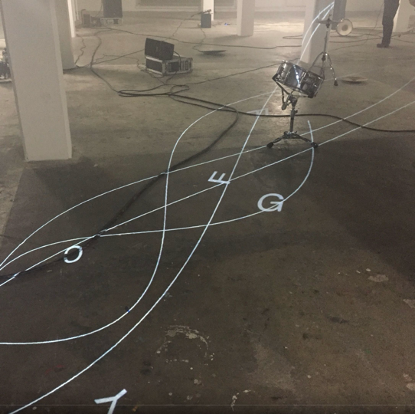

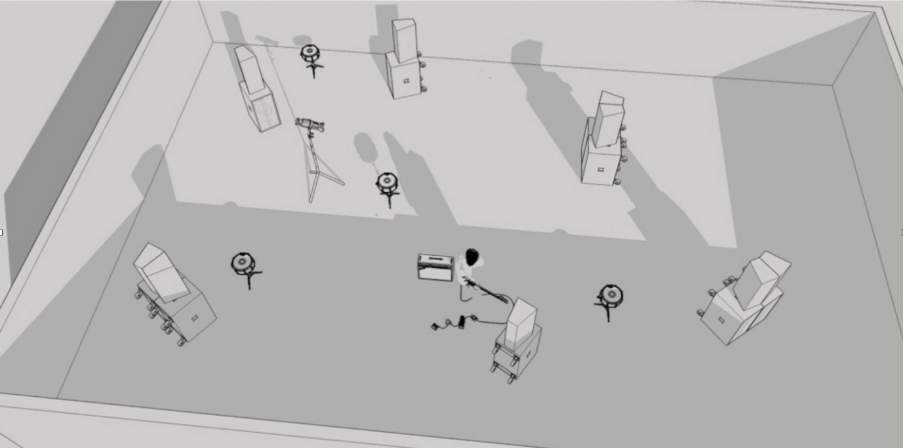

In 2017, I had the opportunity to develop an audio-visual work with artist Konrad Smoleński that dealt with how a score can be mapped in a space. Trackers was created for an open instrumentation, speaker installation, visual objects (including drum kit dispersed in the space), lights, video projector, and smoke machine.

The music notation in a form of video is projected from ceiling to the floor of the performance space with the accompanying multi-channel soundtrack synchronized. Musicians follow the notation playing the letters as they appear, finding ways to interpret the interaction between lines and symbols, and using any features in the space to help this reading of the score. Objects, sounding or otherwise, are used in the space to create situations whereby the interference of score and space is enhanced. A dispersed drum kit, cables and speaker installations that correspond to the number of musicians playing are positioned in the space in a way that there is no space separation between the scene and the audience.

The spatial concept of the piece involves the players moving toward the part of the score they are performing, as though they are discovering the score within the space. The material in the score progresses slowly enough that its movement feels spatial rather than temporal. The visuals of the score feature vibrating lines reminiscent of the lines in a musical score or the strings of an instrument, as well as floating letters.

The conceptual foundation of the piece is inspired by Sophocles' Satyr play Ichneutae (The Trackers or Searchers), particularly the questions it raises about who is permitted to create music and who music is ultimately for[4].

Trackers is very much a durational performance, in that the piece can be played for any length of time. Ideally, durations that go beyond conventional performance should be used. The audience is free to move about the in space, and there is no fixed position or direction in which the piece should be experienced.

Excerpt from Trackers performed by Maze. Full video here.

In a media score, spatiality becomes a core attribute, enabling both performers and audiences to engage with music as a multidimensional experience. Musical elements can be tied to specific locations, objects, or virtual coordinates, allowing for a dynamic interplay between movement, perception, and sound. This reimagining of musical structure not only disrupts traditional linearity but also creates a sense of immersion and agency, as participants explore and interact with the score in a physical space. Once can say that there is a blending and rebalance of temporal and spatial modalities.

Next: Mutability

Notes

[1] https://www.jonroseweb.com/f_projects_great_fences.php

[2] https://www.taogvs.org/reading-as-bodies

[3] Score of the piece and documentation of performance can be found on his website: https://www.ciciliani.com/11-rooms.html.

[4] The piece and the ideas behind it are described in a video lecture I gave for Musica UNAM, Mexico during lockdown. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wxEXak6rzQs