4____Adaptability

As mentioned earlier, descriptive notation is very good at conveying information within the traditional musical parameters of pitch, rhythm, dynamics etc. This specialisation of learning to translate this information to a voice or instrument is at the heart of western musical culture. Where this kind of notation breaks down, is when we want to describe sound or the intention of sound that goes beyond fixed parameters. In the 20th century composers have used traditional notation in an inventive way to push at the limits of these possibilities, think of Giacinto Scelsi, Iannis Xenakis, Brian Fernyhough and others. or even composers who have tried to deconstruct the rules of this language in graphic form: Cornelius Cardew, Sylvano Bussotti, Christian Wolff.

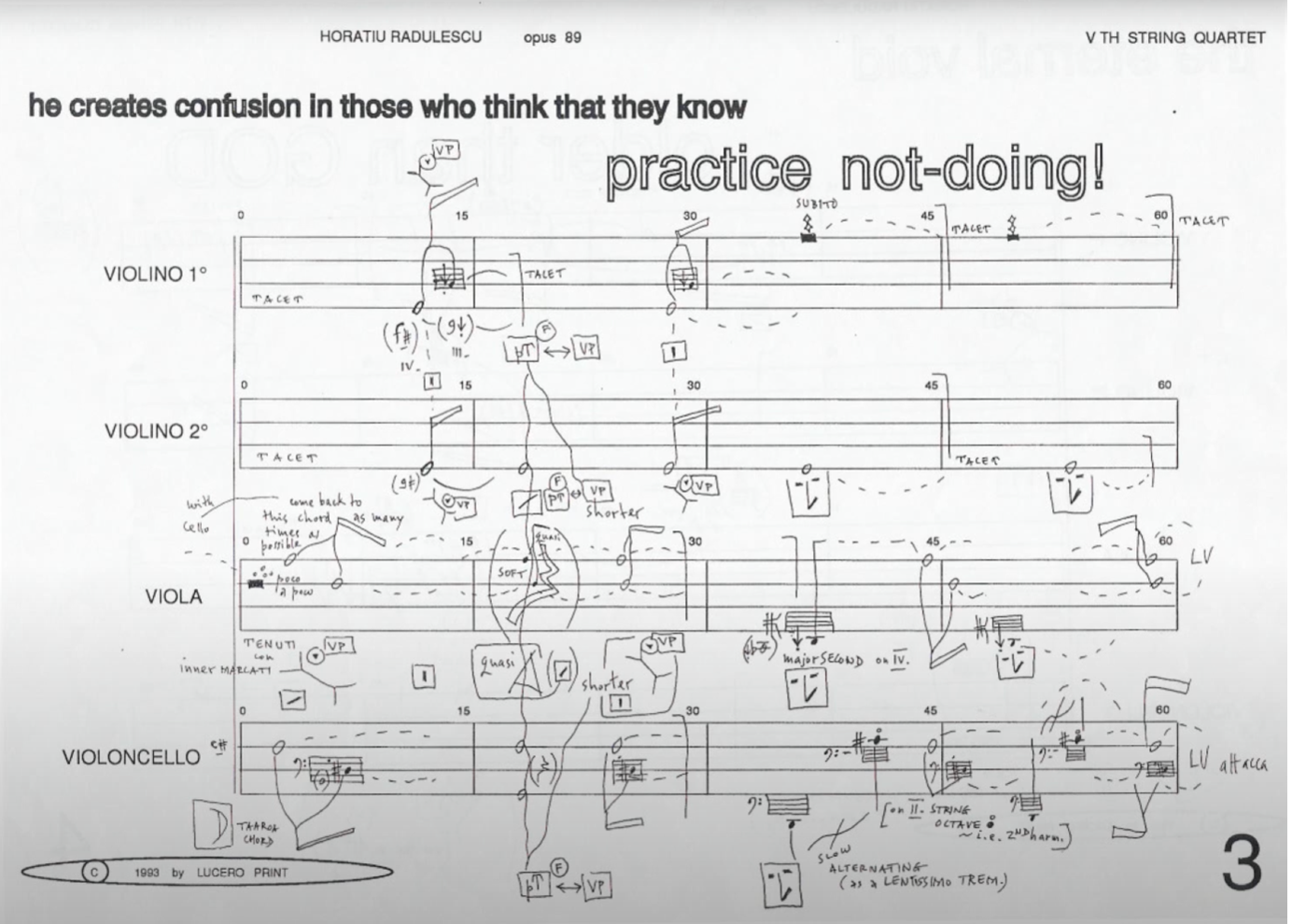

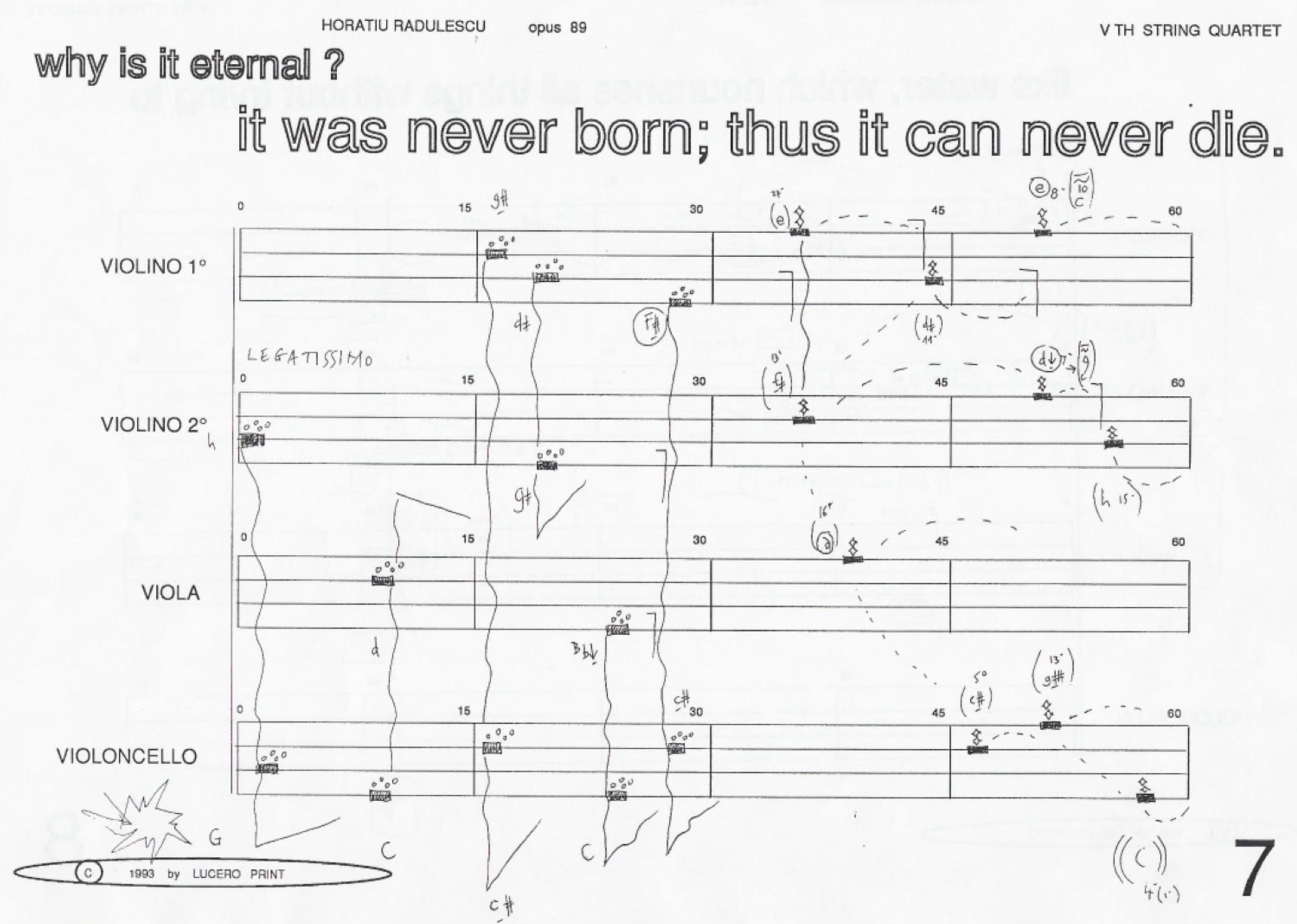

Traditional notation is often less suited to describing unstable parameters such as timbre, fluctuating tempo, non-standard tunings, or cases where the amplitude of sound carries more significance than can be conveyed through standard gradations of piano and forte. Expanding on traditional notation allows for a focus on different aspects of sound. A striking example of this is Horatiu Rădulescu’s 5th String Quartet, Before the Universe Was Born, a remarkable work that delves into the extremes of spectral writing for strings, employing both prescriptive and descriptive notation. The composer has to think outside the box, to convey the specific timbral gestures that the piece requires.

For certain musical instruments, traditional notation becomes less applicable. This is particularly true for electronic instruments, where the complexity of sounds and sound processes often cannot be effectively conveyed using the five-stave system. Similarly, this limitation arises with self-made or traditional instruments played by musicians who employ expanded or self-taught techniques. These challenges raise the question of whether a single type of notation can accommodate a wide variety of instruments and practices or whether more instrument-specific notation systems are needed. In either case, composers frequently need to develop solutions that supplement conventional notation to address these complexities.

Two notable examples from the 1960s that address the issue of notation of unconventional instruments are John Cage’s Cartridge Music (1960) and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Kurzwellen (1968). Both works exemplify an approach to working with electronics that is neither strictly descriptive nor prescriptive but instead emphasizes a “process”. This concept of process lies at the core of many so-called “open form” scores, which propose situations or methods for engaging with an instrument or the relationships between performers, without dictating a specific end result.

For open instrumentations, Stockhausen’s Kurzwellen is a prime example, while for newly invented instruments with unknown sonic possibilities, process-based approaches offer greater flexibility. Such methods allow performers to shape the outcome of a piece, extending the concept of composition beyond a mere sequence of events in time. Instead, they suggest an intention or framework for sound exploration, granting performers more agency to creatively navigate the work.

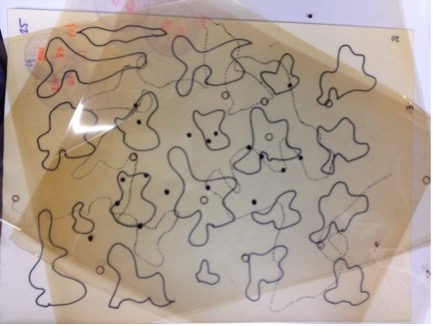

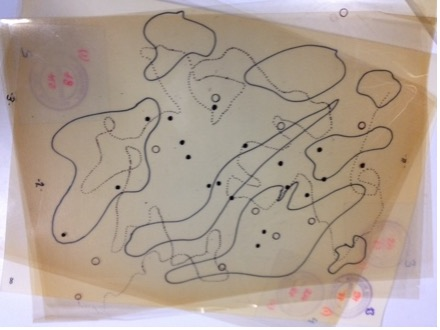

John Cage’s Cartridge Music is a striking score that seems to allude to the dissolution of paper as it’s printed predominantly on transparent sheets. This allows the possibility of combining the different sheets in almost infinite number of ways, creating the indeterminate aesthetic that distinguishes most of Cage’s music. The piece is intended to explore “amplified small sounds”, using cartridges (of phonographic pick-ups).

“In Cartridge Music, the performer is instructed to insert all manner of unspecified small objects into the cartridge; prior performances have involved such items as pipe cleaners, matches, feathers, wires, etc. Furniture may be used as well, amplified via contact microphones. All sounds are to be amplified and are controlled by the performer(s). The number of performers should be at least that of the cartridges, but not greater than twice the number of cartridges. Each performer makes his or her own part from the materials provided[1]”

The idea of process is underlined by the fact that (similar to the Variations series pieces) the performer is required to make their own part. So, one uses the transparencies as an initial step, but thereafter a list of events is created in the performer’s own script that pertains to the specific instrumentation and way of playing that is relevant for their own set up.

The actions are described in relation to how the dotted line intersects with the stopwatch circle, the dots, and the shapes. There is also a suggestion to use tape loops when the dotted line crosses itself. This piece is brimming with sonic possibilities, shaped by the random configuration of the sheets and the specific setup of each performance. Despite the variations across its many versions, the piece maintains a distinct character in its conception and the creative process it requires. It remains unmistakably Cartridge Music in every iteration[2].

In the mid-to late 60’s Karlheinz Stockhausen developed a series of pieces that he described as process compositions: Prozession, Kurzwellen, Spiral, Pole, and Expo. There was undoubtedly an influence from John Cage, in both the openness of the approach, and the choice of the shortwave radio as the central sound source (in Kurzwellen and the subsequent pieces). The concept of "process" was a central theme in the art world at the time, exemplified by the minimalist art movement. However, Stockhausen develops a uniquely musical interpretation of process by fixing certain formal aspects of the composition—such as the sequence of meta-events—while leaving the choice of sounds open. In my opinion, Kurzwellen is the most articulate example of this approach.

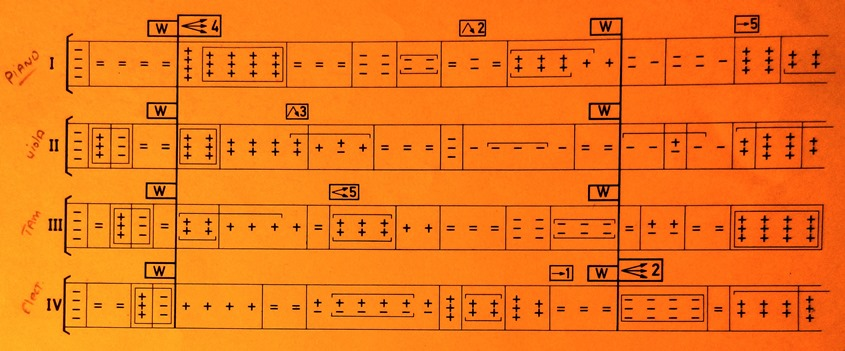

The score uses a series of plus, minus, and equal signs to indicate what kind of progression is made from one event to the other. These signs are applied to four parameters, “rhythm, timbre, melodic contour and envelope”. Parametric thinking was very much a feature of the mid-20th century avant-garde way of thinking about sound, and this was a clear example of how terms coming both from classical world (rhythm and melodic contour) were mixed with terms that are more associated with electronic music (timbre and envelope). So, in this case, plus might refer to “Higher register / Louder dynamic / Longer duration / More segmented rhythm”, and minus, the opposite: “Lower / Quieter / Shorter / Less segmented”.[3] The players have both instruments (which Stockhausen specifies as: tam-tam (gong) with microphonist, viola (with contact mic), electronium[4] or synthesizer, piano, as well as each a shortwave radio. The idea is that the performers search for ‘suitable’ sounds on the radio, avoiding unmodulated clear stations, and can react to that event with their instruments, or to an event of another player. Stockhausen comments about his piece:

“An undreamed intensity of listening and of intuitive playing is reached – and shared by all co-players and listeners – through the concentration of all players on unforeseeable events coming from the realm of short-waves, in which one only very rarely knows who composed or produced them, how they came into being or from where, and in which all possible acoustic phenomena can appear.”[5]

The act of searching for sounds on a shortwave radio and translating them onto instruments constitutes the "process" of the composition. Additionally, the meta-notation—using plus, minus, and equal signs—shapes the flow of sound and the decisions made by the musicians. The abstract nature of this notation makes it highly adaptable to any instrumental arrangement, even though Stockhausen is remarkably specific in this piece, including instructions on how to use an ostensibly unpredictable sound source like the radio. Much like Cartridge Music, this work possesses a distinct sonic character that is unmistakably its own.

Adaptability as a quality of media scores, comes from either the desire or need to work with open instrumentation or new instruments, electronic or otherwise, that deal with parameters that are not so easily expressed in traditional notation. Of course, a score like Cartridge Music is also modular and mutable, but here I am specifically referring to the notation itself. Describing a process, is a way of zooming out from either a descriptive or prescriptive notation, that can give more freedom for the performers to define their sound. What may be lost is a pre-determined fine control over the relation of those sounds, but what is gained is the agency the performers have in fine-tuning it themselves.

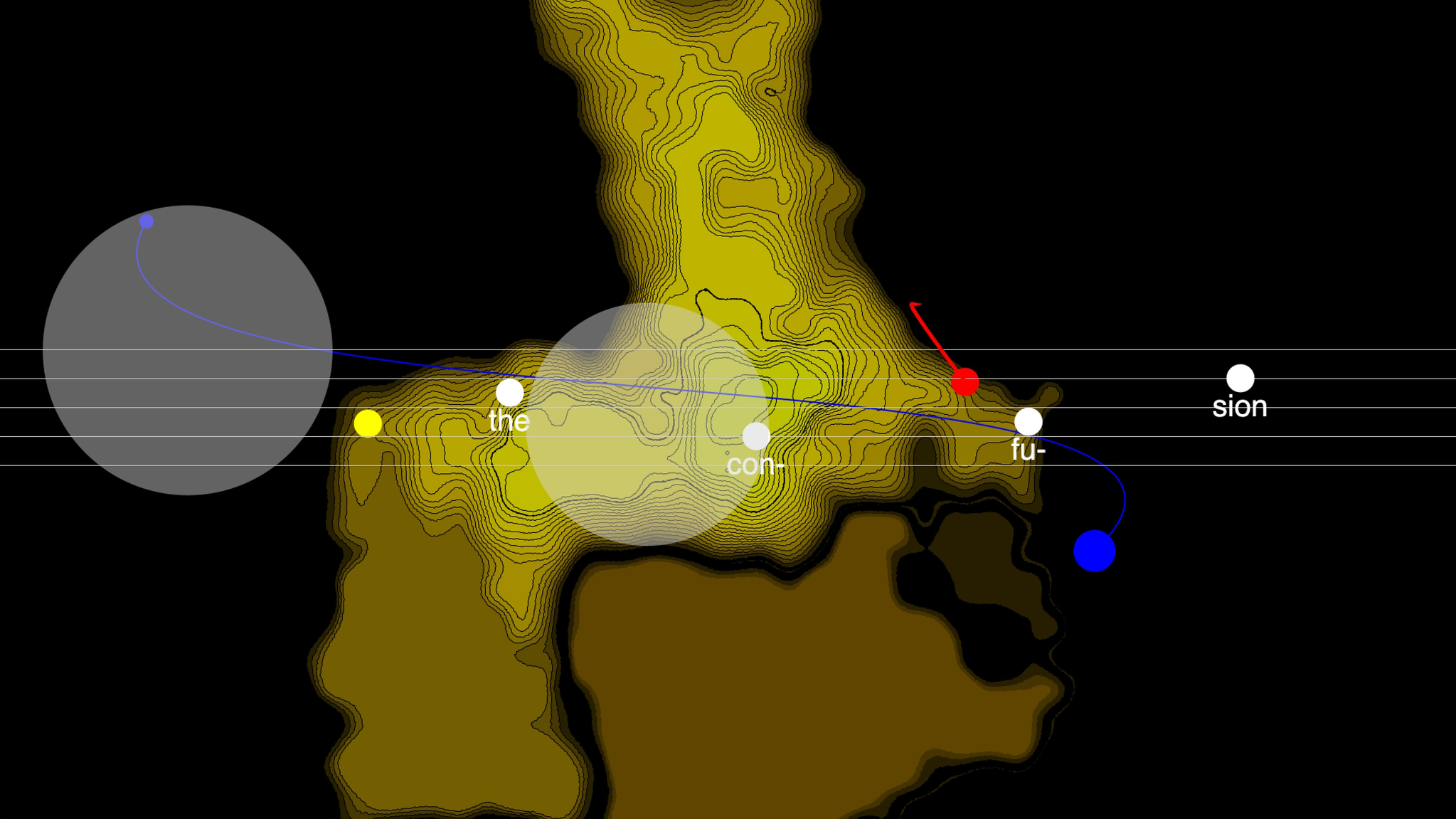

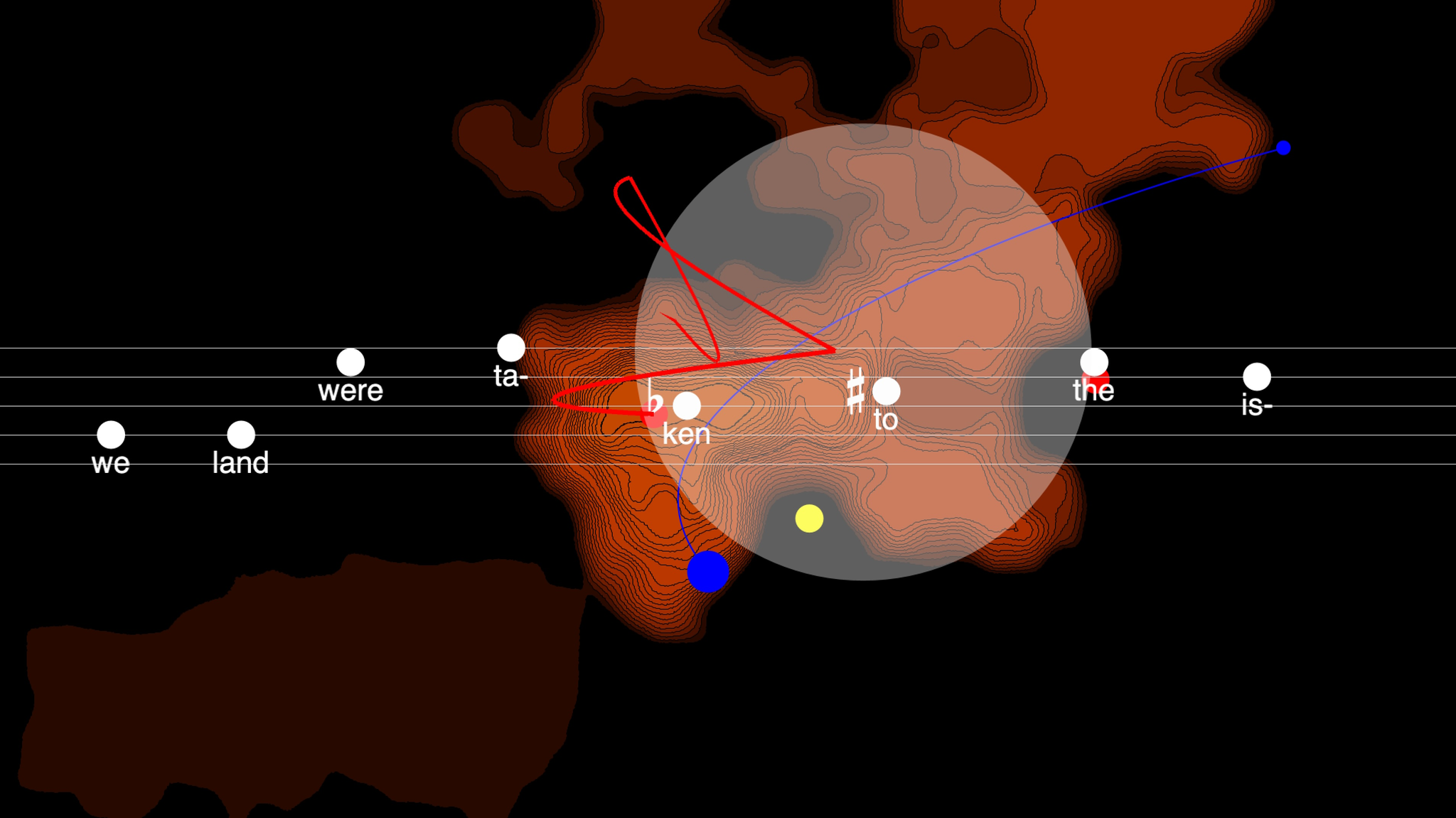

Adaptability in notation can also refer to how it allows for different interpretations depending not only on the instrument but also on the cultural background of the musician. This was a central question I encountered when composing a work, The Island Remained Silent (2023), for The Future Traditions Orchestra, a trans-traditional ensemble of 19 musicians formed in Dresden, Germany, that I also performed with as an electronic musician. The ensemble includes non-Western instruments such as the oud, kanun, koto, kemençe, yaylı tambur, and chang, alongside Western improvisers playing instruments like the violin, trombone, piano, and percussion. The piece embraced the freedom inherent in how these diverse traditions could ornament the generated melodies and interpret the symbols within the score.

The score itself is generated live, triggered by an audio input assigned to specific instruments. The work takes the form of a song cycle, where the auto-generated melodies are not sung but played by the ensemble. While the piece has a strong melodic foundation, this is not fully dictated by the projected notes; instead, it is inferred through various symbols that appear in the score. Many of the traditions represented in the ensemble have rich melodic heterophonic practices where ornamentation plays a vital role, and I wanted this to feature strongly in the work.

The piece is divided into eight sections, each based on texts from authors such as Jean Giraudoux, Daniel Defoe, Lucian of Samosata, William Golding, and J.G. Ballard, about encounters with islands. Each section is based on a different set of melodic and harmonic possibilities, live-generated into a melody paired with the text. Additional symbols in the score guide the musicians: yellow denotes gliding notes, blue indicates an alternating pulse, red signifies an elaborated ornament, and grey represents “cloudy” sounds. These symbols are open to interpretation, allowing musicians to adapt them to their instrument and cultural background, creating a dynamic interplay of traditions within the ensemble.

Excerpts (edited) from The Island Remained Silent performed by the Future Tradition Orchestra, Dresden, 29.04.23. Full video here.

Next: Interactivity

Notes

[1] From the instruction of the score of John Cages’s Cartridge Music, London: Peters Edition.

[2] One of the most interesting performances online of this is by Langham Research Centre: Felix Carey, Iain Chambers, Philip Tagney and Robert Worby filmed by Helen Petts: https://vimeo.com/59864306

[3] Moritz, Albrecht, 2002: https://www.stockhausen-essays.org/kurzwellen.htm

[4] The electronium here refers to a type of accordian-synthesizer, not the Raymond Scott one.

[5] https://stockhausenspace.blogspot.com/2014/10/opus-25-kurzwellen.html